“The past is never dead. It’s not even past” is a flippant line tossed off in a novel by William Faulkner (don’t bother reading it; I did one college summer, when I thought Faulkner novels were something I just had to learn to appreciate, more the fool I) and that quote reflects the theme of the book, which is about the terrible prices we often pay for long-ago mistakes. In recent years it’s been misappropriated to mean history in general, particularly as an upbeat catchphrase for historic places. That meaning fits the town of Sonoma, with its adobes haunted by Vallejo’s ghosts, or Petaluma, with much of its downtown undisturbed since Mark Twain wrote Huckleberry Finn. But Santa Rosa – not so much. Here the phrase has to be used in its original intent, to express the unhappy ways we are dogged by our past.

| – | – |

THE REDEVELOPMENT SERIES THE CITY DESIGNED FOR DRIVING CARS …AND HOW WE GAINED AN UGLY CITY HALL TEARING APART “THE CITY DESIGNED FOR LIVING” MR. CODDING HAS SOME OBJECTIONS

|

This is the 700th article to appear in this journal, which now clocks in at over 1.5 million words (I have statistically typed the letter “e” about 190,530 times but the letter “z” merely 1,110). Normally such a milestone is an occasion for a “best of” recap but I did that not so long ago back at #650 with “650 KISSES DEEP,” so instead I’d like to step back and reflect on some of the reasons Santa Rosa came to be the way it is today.

This is also timely because right now (summer 2019) the city is working on the Downtown Station Area Specific Plan which “seeks to guide new development with a view to creating a vibrant urban center with a distinct identity and character.” The plan calls for wedging up to 7,000 more housing units into the downtown area, which will be quite a trick.

There are limits to what developers can build, in part because this is a high-risk earthquake zone (a 1 in 3 chance we will have a catastrophe within the next 26 years), but a greater obstacle is that Santa Rosa is uniquely burdened by layers of bad decisions made over several decades.

THE ORIGINAL DOWNTOWN PLAN Santa Rosa’s prime underlying problem is (literally) underlying. Scrape off the present downtown buildings and we have the same frontier village that was platted way back in 1853, when there was only one house (Julio Carrillo’s), a store, a tavern and stray pigs. It was small enough for anyone to walk across any direction in a couple of minutes or three – 70 total acres from the creek to Fifth street, from E to A street.

Now eight score and five years since, our downtown core is virtually unchanged from that original street grid – minus the dozens of acres lopped off for the highway and mall – so there ain’t much room on the dance floor for developers to make any sort of dramatic moves.

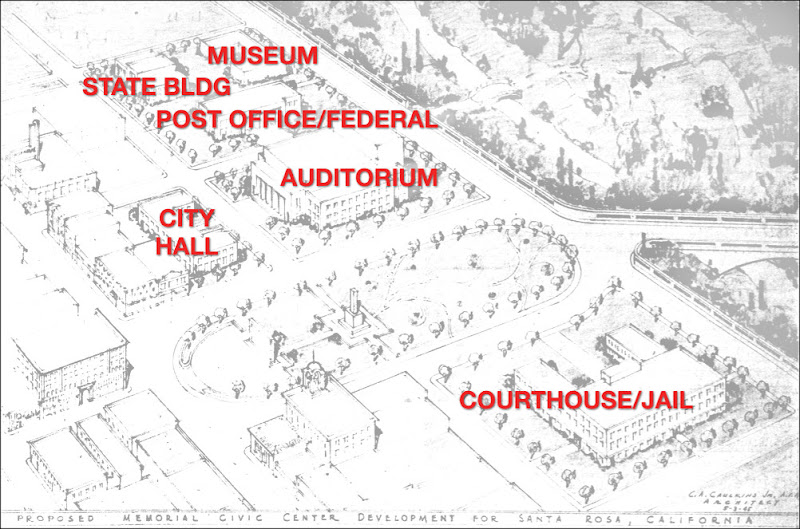

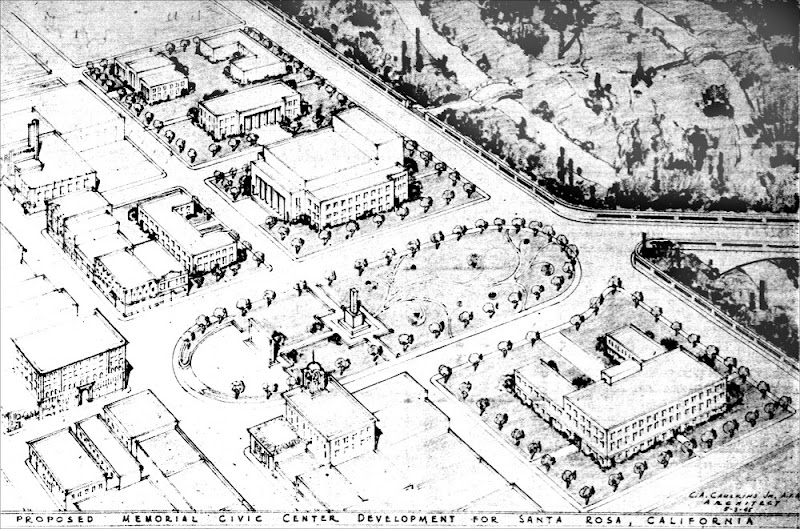

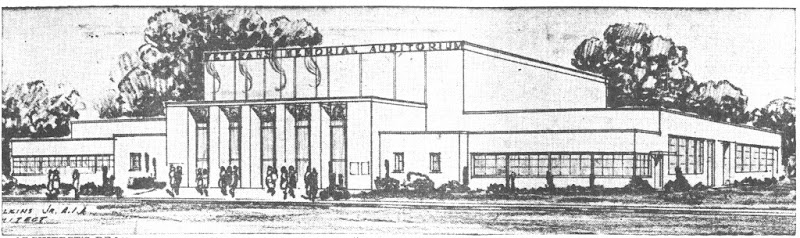

Not that people haven’t envisioned a better downtown. In 1945 architect “Cal” Caulkins created a plan which eliminated Courthouse Square and turned almost all of the space between First and Third streets into a Civic Center. No question: This was the best of all possible Santa Rosas, as I wrote in “THE SANTA ROSA THAT SHOULD HAVE BEEN.” The plan had universal and enthusiastic support and only needed voter approval of a $100k bond to get started. It lost by 96 votes on a ballot crowded with other bond measures. Attempts by the Chamber of Commerce to revive a modified version of the design in 1953 went nowhere.

Another big attempt to fix Santa Rosa’s design problems came in 1960-1961, when the city’s new Redevelopment Agency hired urban design experts from New Jersey. Some of their ideas were pretty good; they envisioned a pedestrian-friendly city with mini-parks, tree-lined boulevards and a greenway along both banks of a fully restored Santa Rosa Creek. Their objective was for the public to drive to a parking garage/lot as easily as possible and walk.

Over the following years came a succession of consultants and developers with both detailed schemes and spitballing proposals, mainly focused on revitalizing Fourth street by making it more walkable. (Most innovative was an idea to rip out the roadway and replace it with an artificial creek criss-crossed by little footbridges.) In 1981 it was rechristened the “Fourth Street Mall” and closed to autos on Friday and Saturday nights to squash the local street cruising fad, topics covered in “POSITIVELY PEDESTRIAN 4TH STREET.”

Tinkering does not a city remake, and downtown is still as it always was, an Old West village square. As I’ve joked before, the town motto should be changed from “The City Designed For Living” to “The City Designed For Living…During the Gold Rush.”

THE PRICE OF PARKING Or maybe the motto should be, “The City Designed For Buggies.”

For a city with such a small downtown, Santa Rosa devotes a big hunk of that footprint to automobile parking, with nine lots and five garages. Yet should even half of the new residents in those 7,000 proposed apartments/condos have a car, every single parking spot will be taken – and then some.

Santa Rosa has always had a fraught relationship with autos, and it’s again because so much of the core area is unchanged from its buggywhip days. Once beyond the eight square blocks around Courthouse Square many of the old residential streets are so narrow that parking is not allowed on both sides and it’s still a squeeze when trucks or SUVs pass. Again, high-density development would be tough. (The exception is College ave. which is quite wide because they drove cattle down the street from the Southern Pacific depot on North street to the slaughterhouse near Cleveland ave.)

Complaints about downtown parking go back to 1910, when farmers coming to town in their wagons for Saturday shopping found fewer hitching posts available. In 1912 the city finally gave in and set up the vacant lot at Third and B streets as a kind of horse parking lot.

From the 1920s onward, photos of downtown show seemingly every parking spot taken. There was no shortage of articles in the Press Democrat detailing the latest plans to solve the parking problem – including 1937’s increased fines for every additional violation, which reveals a major drawback of living in a small town where the Meter Lady knows everybody.

The crisis came 1945-1946, when the city introduced parking meters along with Santa Rosa’s first sales tax, both to predictable taxpayer howls. The Press Democrat’s letter section saw writers interchangeably angry between the tax and the parking meters and although the tax was only one percent, there were calls for a complete boycott of the downtown as a kind of Boston Tea Party protest. On top of that, street parking was dreaded because the city insisted upon parallel parking only, even though merchants had been protesting it for many years. (Those pre-1950 land-yachts did not have power steering, so turning the wheels when the car was not in motion was a helluva workout.) For more on all this feuding see: “CITY OF ROSES AND PARKING METERS.”

Whilst the normally peaceable citizens of Santa Rosa were stabbing their City Councilman dolls with voodoo pins, a guy named Hugh Codding was building a new shopping center he called Montgomery Village. It opened in 1950 with an advertising blitz promoting no sales tax (because it was outside of city limits) and easy, meter-free parking. Shoppers flocked there. Thus closed the first chapter of a big book we might call, “A Series of City Hall’s Unfortunate Events.”

OUR WAY OR NO FREEWAY City Hall alone was not to blame for all that era’s dreadful decisions; together with the Downtown Association and Chamber of Commerce they “sawed the town in half,” as a Press Democrat editor put it in the paper’s 1948 end of year wrapup.

As well known from old photos, the Redwood Highway – AKA Highway 101 – used to pass smack through downtown Santa Rosa, around Courthouse Square and up Mendocino ave. This traffic included not only your aunt Ginny running errands across town but big trucks passing through with redwood logs, cattle, farm equipment and such. It may have looked like the City of Roses, but it probably smelled like the City of Diesel.

In 1938 there was a municipal bond measure to fund an alt truck route around downtown. It failed to pass but would have pushed all that heavy traffic over to Wilson street, which was the heart of our “Little Italy” community – although the ads for the bond pleaded it was urgently needed for the safety of our school children, that concern apparently didn’t extend to the Italian kids. Backers also warned this truck route was necessary because the State Highway Commission might otherwise build a bypass and turn Santa Rosa into a “ghost town.”

In 1938 there was a municipal bond measure to fund an alt truck route around downtown. It failed to pass but would have pushed all that heavy traffic over to Wilson street, which was the heart of our “Little Italy” community – although the ads for the bond pleaded it was urgently needed for the safety of our school children, that concern apparently didn’t extend to the Italian kids. Backers also warned this truck route was necessary because the State Highway Commission might otherwise build a bypass and turn Santa Rosa into a “ghost town.”

A couple of years passed. The city’s Grand Poobahs were still stuck on the idea of a truck route but now wanted it a block closer to downtown, on Davis st. (or rather, between Davis and Morgan streets). The state offered no firm counterproposal; maybe they would construct a bypass somewhere west of Santa Rosa or perhaps use the Davis st. route with a short five block overpass, similar to what they were currently building in San Rafael. Anyway, there was no urgency: The state estimated there were only 4,500 daily trips along this stretch of highway 101 (today there are about 100,000).

Come 1941, however, the Press Democrat front page screamed with 72-point headlines – not just about the war against Hitler, but the war against the Highway Commission.

“An insult to Santa Rosa!” raged a PD op/ed after the state announced it was going to build a 13 block overpass through the town, from Sebastopol road to Ninth st. The paper called this a “highway on stilts” and the Downtown Association lawyer said it would “create the impression that the city is nothing more or less than a ‘slough town.'”

Santa Rosa’s response came in another banner headline: “CITY TO BUILD ALTERNATE TRUCK HIGHWAY!” They quickly bought right-of-way from seven homeowners between South A and South Davis streets (moving one of the houses), paved the stub of a road, and because the Commission didn’t grunt in disapproval, the town declared victory. The next thing anyone knew was when a state engineer was found surveying for the overpass and told someone it was “absolutely necessary at this time.”

I will mercifully spare Gentle Reader the full drama of what happened between 1942 and 1948, except to say that the Press Democrat wore out its supply of lead type exclamation marks (“CITY TO FIGHT OVERHEAD HIGHWAY!”) as it breathlessly reported all the good news about how the damned “Stilt Road” was not just merely dead but really most sincerely dead. And then another surveyor showed up from Sacramento. Nope.

There were in toto six different routes under consideration by the Highway Commission; unfortunately, not all of them were detailed in any Sonoma county newspapers (as far as I can tell). There was always the threat of a complete western bypass, but it was never mentioned whether that route would have been Stony Point or Wright/Fulton, or both. Serious consideration was given an eastern route from Petaluma Hill road to North street, curving back to Redwood Highway/Mendocino ave. between Memorial Park and Lewis road – which would have brought the highway rumblings within earshot of the tony McDonald ave. neighborhood, of course.

The state finally relented and gave Santa Rosa what the Poobahs wanted – a ground-level freeway that mostly wiped out Davis street (it’s the same route of highway 101 today). There were eleven crossings on it between Sebastopol road and Steele lane so there were plenty of chances to turn off and do some shopping.

Our ancestors fought so fiercely for this layout because they believed the downtown business district would wither if there was a bypass – that Santa Rosa couldn’t survive unless shoppers were only seconds away from their favorite stores. But I suspect another reason was because they didn’t actually grasp the concept of freeways. It was the mid-1940s, remember, and the very first one in America (Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles) had been constructed just a few years before. From some of the remarks in the PD it appears they thought of an elevated freeway like a bridge, where there was no getting on or off in midspan; when road options were presented at hearings in Petaluma, state officials had to explain that a freeway included a certain number of on and off ramps.

By contrast, when Petaluma’s highway improvements came years later that town had the opposite attitude – the state could not build their downtown bypass fast enough. “Loss of the tourist trade will be more than offset by an increase in local trade,” their City Manager said before work began. Petaluma’s greatest concern was the route be chosen with care to avoid the “poultry belt” because of “the harmful effects of irregular noises, headlights and police sirens on white leghorns,” as a freeway skeptic remarked.

The grand opening of the “Santa Rosa Freeway” was May 20, 1949. Less than two months passed before the first fatality: George Dow was killed in July when a car turning onto West College crossed his southbound lane. After that someone died every ten weeks on the average until the PD wrote a 1950 editorial which began, “A state highway ‘deathway’ runs through Santa Rosa. It is mistakenly called a ‘freeway.'”

Remember the joke that a camel was a horse designed by a committee? This was a freeway designed by shopkeepers. Of the eleven crossings only seven had stoplights. The only turn lanes were on the southbound side for turning east onto Third, Fourth and Fifth streets – to make it easier to get downtown, of course – otherwise drivers shot across oncoming traffic. Crossings at Steele Lane, Fifth St. and Barham Ave. proved the most deadly and the city asked for more traffic lights; the state replied they would study the safety issues concerning the road they told us they did not want to build. Meanwhile, the speed limit was cranked down from 55 to 45 to 35 as the death toll mounted and the city discovered there was more cross-traffic than there were cars using the highway.

Then there was the community impact. The PD sent out a reporter in 1950 to talk to people living on the west side. He was told the freeway made them feel stigmatized – they were on the “wrong side of tracks.” And so they were; there were no parks around there at the time except for a single weedy lot. Their 400+ kids had to walk across the freeway to go to school (mainly Burbank Elementary), so the city built a pedestrian underpass at Ellis Street. It flooded during heavy rains.

There was no whitewashing the fact that the freeway was a disaster in every way, and no doubt about who was to blame for it being like that. But curiously, the Press Democrat no longer mentioned the names of the guys it had long praised for standing up to those smarty-pants state engineers just a few years earlier.

Santa Rosa’s City Manager Sam Hood spoke to the San Francisco Commonwealth Club in 1951 and said the “selfish interests” who were to blame for forcing through the ground-level roadway had come to find the freeway had no impact on their business at all. He added that if a vote were to be held that day – less than two years after the freeway opened – not one merchant would oppose a bypass.

The PD managed to both strongly condemn the freeway (“every intersection is a death-trap”) while making its original boosters – including the paper itself – even more anonymous in a 1956 editorial: “…well-intentioned Santa Rosans, laymen who thought they knew more than highly experienced and qualified engineers, who kicked, screamed and protested until they had their way – and saddled Santa Rosa with a classic example of what happens when local pressure-groups have their way.” So forgiving.

Santa Rosa finally yielded to the state and planning began for what we have today – an elevated highway 101 directly above the old ground level version. When work began the PD printed an Aug. 24, 1966 feature on the detour plans and expressed relief that the end was nigh for our “17-year-old mistake.” The new freeway opened October 1968 and cost $3.8M.

The old Santa Rosa Freeway may be no more but its terrible legacy remains, forever splitting the city between east and west. Whatever happens to this city – a population boom, catastrophic earthquake or fire, sweeping redevelopment or no development at all – that highway will endure and shape what we can do with our future. In Santa Rosa it will always be 1949.

(Photo at top courtesy Larry Lapeere Collection)