His name was James Dalzell Brown. Should you dig up your great-grandparents (and please do not do so simply on my account) and asked them who the “bank wrecker” was, they would not have hesitated to spit out his name. Had they lived in Petaluma around 1910, there might have been some cussing along with actual spit.

Before plunging forward, a short prologue and apology: This is part II of the previous article, “DREAMS OF AN EMPIRE OF OIL” which covered Petaluma’s ill-fated oil and gas boom through part of 1910. Players introduced there are discussed in greater depth below, so Gentle Reader might wish to review it before continuing (the article’s not that long).

This article, however, is very long and I do apologize for that. But this is an incredible story which has never been told, even though Brown was a criminal with plans extraordinaire. (Honestly, I don’t understand why there hasn’t been a book, movie or documentary mini-series about this guy and his gang of pirates.) To make this easier to read in more than one sitting there’s an option of hopping past the Petaluma oil saga and going directly to the part about Brown’s crazy schemes.

The takeaway from this story should be that Petaluma was lucky it didn’t become the West Coast hub for oil and natural gas in 1909. Undoubtedly Brown and his boys would have exploited the town and anyone who mistakenly trusted them – and we know they would’ve done so because a pair of them did manage to scam a few Petaluma residents, as you’ll discover at the end of this article.

So let’s now pick up where part I ended: In 1910 Petaluma’s elation over striking oil began to crumple in September after the town’s papers printed a letter from the State Mining Bureau. Cassius Webb, acting as the attorney for Ramona Oil, asked them how much the oil field was worth so Consolidated Oil could start paying dividends within a couple of months.

The Bureau’s response was brutal. First, it was their view there was “little or no chance” of hitting large quantities of oil. Some of the company’s expectations were “entirely ridiculous” and “it would require considerable time to put the property in paying condition.” Webb’s claims seemed “intended to deceive the most ignorant” and it was the Bureau’s opinion the project had “all the earmarks of deliberate fraud.”

Needless to say, the letter “created a great sensation” in Petaluma, according to the Argus. It was “about the worst blow yet delivered at the men who have staked their reputations and their money on finding oil in paying quantities in this vicinity.”

General Manager John Frank told the newspaper everything was going according to plan. “The English stockholders have every confidence in the success of our development work” because he was a bonafide oil expert; Consolidated Oil respected him so much he was given the pick of any oil fields around the state and he chose the one near Petaluma as having the best prospects. The state Bureau had not visited the site and didn’t know what they were talking about.

As for the stockholders in the Ramona and Bonita Oil companies, not to worry: Their old shares were to be traded in one-for-one with stock in Consolidated Oil, which was then listed at $2.50 per share (over eighty bucks today). Everything was going to work out just fine.

Everything did not work out just fine.

About four months later, John Frank published an extraordinary open letter to Ramona stockholders. The big reveal: All work was shut down. He and the drilling supervisor were no longer allowed on the premises. Stockholders had probably lost their entire investment. And the man secretly behind the curtain the whole time was the infamous J. Dalzell Brown. At that news, you can bet a squawk of horror resounded throughout the Petaluma valley.

We’ll begin by looking at John W. Frank, who was considerably less than he claimed to be. Born in 1865, he stated on the 1910 census he was an “oil locator;” ten years before that, he was simply a miner. He made a big splash in Bay Area papers in 1905 by announcing he had invented a device that could find shipwrecks which was patented (it couldn’t and it wasn’t).

Over the next few years Mr. Frank can be spotted in newspapers and trade magazines posing as an expert in finding oil. He boasted of finding oil in Nevada, Washington, California, Texas and Canada. To investors in Colorado Springs he promised his track record was perfect – all of his finds had resulted in productive wells. Oddly, he never named any specific examples.

In 1907 Frank became acquainted with Dalzell Brown and his cronies: Norton C. Wells, Charles Gregg and Dalzell’s son, Thomas.1 (More about this group in the following section.) Gregg had been contacted by the penny-ante Petaluma Oil and Development Company which had an oil lease on the Ducker ranch that looked promising, but was unable to raise capital to do actual drilling.

Together Frank, Brown, Wells and Gregg formed the Ramona Oil Company although Brown’s name was not made public. They made a deal with Petaluma O&D which still held the Ducker lease; Ramona would take over the prospecting work and any profits would be split evenly between the companies.

Dalzell Brown was expected to underwrite the operation even though officially he was broke, with a conga line of prosecutors and plaintiffs queued up to sue him for various financial misdeeds. Brown told his partners he would dip into $30,000 in securities which were kept under his wife’s name. It’s unclear how much money he actually put in to support day-to-day operations, and wording in Frank’s letter to shareholders suggests it was little or even nothing at all. But through a separate company set up by Brown and his son, he owned all the equipment including the very expensive drilling rig and the mighty one horsepower (!) motor that powered everything.

(RIGHT: J. Dalzell Brown 1908 San Quentin mug shots)

(RIGHT: J. Dalzell Brown 1908 San Quentin mug shots)

The other tiny little difficulty – just an annoyance, really – was that Brown was in San Quentin at the time for embezzlement. Frank was the conduit between the Ramona partners and prisoner #22849, both via prison visits and correspondence. A letter to him was later used as evidence in a lawsuit: “On my release it is my intention to devote my entire time and energy to the oil business, and I join with you in the wish and hope that we may make lots of ‘easy clean money’ together. J. D. B.”

Brown soon discovered there would be no “easy clean money” flowing from the Petaluma oilfield. Soon after constructing the Ramona well derrick they were already running out of funds. Brown agreed to keep work going by directly investing $5,000 in exchange for another 100,000 shares of stock. Brown was now the major stockholder with 200k shares, as he already had 100,000 in “promotion stock”.2

Prospects began to look up in 1909. John Frank was selling lots of stock (which was likely his true forté instead of finding oil) and the Ramona well hit a strong pocket of natural gas, which made folks in Petaluma giddy because it was assumed the gas would be piped to town and lead to expansive growth. They began drilling the Bonita well and formed the Bonita Oil Co. which meant a million more stock shares for Frank to peddle.

The Bonita well also struck natural gas but soon caved in, and the Ramona well likewise collapsed.3 Dalzell Brown was now released from prison and living in Los Angeles, where he summoned Frank to discuss what was to be done. Brown wanted to close the companies down and walk away.

“What do you intend to do with our stockholders who have put up their money in good faith?” Frank asked, according to his open letter to Ramona stockholders. He replied, “they can as well afford to lose their money as I can lose mine” (paraphrased by Frank) and wished somebody would buy him out.

Frank revealed he had the power to sign contracts on behalf of an English syndicate (a couple of years earlier, he had looked over some land in West Virginia for Consolidated Oil). Brown asked, “Well, why don’t you get them to take it over?”

Over the following months Frank worked out a deal between his partners and Consolidated, which was already planning to invest $30M in California oil projects (about a billion dollars in today’s value).4 Frank and the others would continue working at the site.

It was agreed Ramona and Bonita company stockholders would swap their shares for the equivalent number of Consolidated Oil Fields of California shares, which were then being sold in London for ten shillings, about 10x the value of the old Ramona and Bonita stock.5 Quite a payday! To protect those investors – particularly since there was still no proof the oilfield would be productive and it was unclear if the gas wells could be brought back online – all the partners also agreed to return their enormous stash of promotion stock.

It was agreed Ramona and Bonita company stockholders would swap their shares for the equivalent number of Consolidated Oil Fields of California shares, which were then being sold in London for ten shillings, about 10x the value of the old Ramona and Bonita stock.5 Quite a payday! To protect those investors – particularly since there was still no proof the oilfield would be productive and it was unclear if the gas wells could be brought back online – all the partners also agreed to return their enormous stash of promotion stock.

Less than four months after that deal was made a new well struck oil. As described in part I, in Petaluma limitless joy abounded. Even a skeptical report from the State Mining Bureau couldn’t dampen everyone’s high spirits.

Enter chaos agent J. Dalzell Brown.

Brown went back on his word to return those 100,000 promotion shares, which put him first in line to receive Consolidated stock worth nearly a quarter million dollars. According to Frank’s letter to stockholders, Brown was paid in full. (Don’t forget he still had those additional 100k shares of regular stock mentioned above).

Recall, too, he had a side business that actually owned the drilling equipment. Once Consolidated entered the picture he agreed to let the company use his gear for three months free, but after that he wanted $15/day rent or them to buy it for $4,500. After the oil was found Frank received an urgent telegram from Consolidated: Brown had shown up in London and demanded full payment for the rig – what should they do? Frank told them not to pay Brown, that the valuable drill would be returned to Brown’s company.

At about the same time, an item appeared in a widely-read UK petroleum newsletter that “created dissension” among English stockholders according to Frank, but no further details can be found. Later a trade magazine commented there were “…damaging reports that have been published concerning the properties of the company and the statements that have been made about them…in order to allay the fears of the stockholders an extraordinary general meeting was held at the office in London…”

We can guess at two possible reasons for such a kerfuffle: It was discovered that A) an internationally known criminal was at the center of the deal, or B) there were viable rumors that Frank or someone else had “salted” the well which appeared to strike oil. Frank acknowledged there were whispers in an interview with the Argus: “Some people have gone so far as to express the belief that we salted this well…” True or no, the suspicion became part of the common view, and ten years later the Ansonia Oil Co. brought it up during a public meeting in Petaluma to assuage concerns about their honesty.

Then at the beginning of 1911, the Ramona Oil Co. sued Consolidated Oil Fields of California along with several individuals, including Frank. (At that point Ramona directors were down to just Brown, his son and Norton C. Wells.) As the suit was filed in England I’m unable to find the complaint; it doesn’t appear to be described in any newspaper or journal available on the internet, but presumably it must not have been much more than a nuisance suit to the huge British firm. At the same time Frank and the others were locked out of the oilfield.

And thus endeth Petaluma’s first oil venture. After that squirmy meeting with stockholders Consolidated never mentioned the project again. Frank headed to British Columbia (about which more will be told in the next chapter) but came back here to testify against Brown in bank fraud prosecutions in San Francisco.

The rest of 1911 was consumed with legal actions against Brown to sell off his equipment at sheriff’s auctions for debts. Superintendent K. V. McDonald hadn’t been paid for months and wanted over $1,000 for labor. Frank said he was owed $600 in commissions for selling stock. A delivery man named H. H. Kercheval filed for $167. More attachments were claimed for the pumps, the horsepower engine, pipes and boilers. Brown did not contest any of that; at the time he was reportedly running a cemetery association somewhere in Los Angeles.

Superintendent McDonald ended up buying the fabled Ducker oil lease for all of $90.

Petalumans of a vintage age might recall there were indeed productive oil wells operated by Shell Oil east of Petaluma. Those projects began several years after the events described here and did not involve any of the same companies or people. Researchers interested in exploring that history should seek out references to the Ansonia Oil Co. between 1921 and 1928.

Until late in 1907, J. Dalzell Brown had it all…and then some.

He didn’t see himself as a grifter. He thought of himself as a savvy businessman who recognized great risk can yield great rewards. Nor did his accomplices view themselves as cheats, liars or dupes; they thought they were smart guys who would enrich themselves by following his road to riches. And he certainly didn’t set out to screw over Petaluma in particular. To him, Petaluma and Santa Rosa were just podunk farm towns he passed through while he and his wife were being chauffeured farther up north.

Brown was born in Scotland in 1864, met his wife Harriet Skimmings in Halifax and the two moved to San Francisco in 1886. Four years later, he’s named as the manager and treasurer of the California Safe Deposit & Trust Co. There he brushed elbows with Isaac G. Wickersham, a company director and famed Petaluma banker – the first of many from Sonoma County who would cross his path.

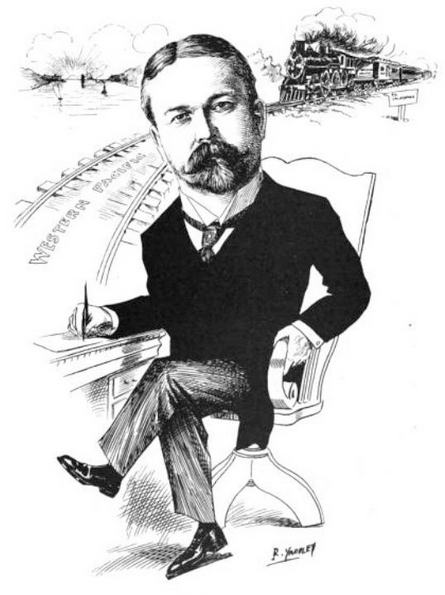

Around the turn of the century he was a founder of two short railroad lines.6 In 1903 both were acquired by a brand-new company called the Western Pacific Railway with Brown as the treasurer. It soon became clear that railroad was intended to be part of a transcontinental line.

Around the turn of the century he was a founder of two short railroad lines.6 In 1903 both were acquired by a brand-new company called the Western Pacific Railway with Brown as the treasurer. It soon became clear that railroad was intended to be part of a transcontinental line.

Gentle Reader may be thinking right now, “gosh, ol’ Dalzell sure had a lot on his plate, being the treasurer of a railroad with big ambitions as well as the VP/manager of a major San Francisco bank!” Welp, sir, the fun’s just getting started. J. Dalzell Brown wanted to turn Latin America into his personal fiefdom – or something like it.

“Brown had visions of vast South American estates with himself as the greatest grandee of the western hemisphere,” reported the San Francisco Call in a widely reprinted feature story. “[H]e had persuaded many leaders in the Central and South American countries to deposit their money in his bank. He succeeded in gaining their friendship, and among the names of the depositors will be found those of several hundred Latin Americans.”

Counted among them was John Moisant, an American who owned a coffee plantation in El Salvador. His profile is worth a detour; Moisant tried to overthrow the country’s junta and learned to fly so he could attack Salvadoran troops by air. He returned to this country and became a major aviation pioneer around 1910, nearly as famous as the Wright brothers.

Comparisons to King Leopold and the Congo were easily made as Brown considered buying Moisant’s plantation for his base of operations to monopolize rubber, banana and timber interests. He convinced San Francisco investors to buy stock in some of these plantations and gained credibility by being appointed Uruguay’s consul for San Francisco.

Was he seriously planning to swoop into South America and take over whole sections of its economy? Hard to say, yet it’s very believable he wanted to be the U.S. banker for wealthy South Americans and their governments. But he never traveled further than Mexico in his life, so he didn’t build the personal relationships to pull off such a stunt. And besides, at the same time he was busy building an empire of another sort in Lake County.

As discussed here some time ago, Lake county was then promoted as the “Switzerland of America” with tens of thousands of visitors drawn to its mineral spring resorts and spending weeks there every summer. Boosters were certain the place had unlimited potential if there only were some way to easily reach it; as it was, the only way to get there was via teeth-rattling roads. A series of proposals were floated to construct a railroad or even an electric trolley from Santa Rosa but none advanced very far.

Brown owned about three miles of Clear Lake frontage, riding on the coattails of a developer who had bought up 35,000 acres around the lake. The plan was that hotel resorts would dot the shoreline, visitors would step off that future train/trolley at Lower Lake or Lakeport and take a water taxi to wherever they were staying. They also intended to construct an 84 mile boulevard around the entire lake and reforest the area by having the state forester plant 200,000 native and ornamental trees (they ended up with several hundred blue gum eucalyptus).

As an early investor Brown also bought the Lakeport hotel and gave it a first-class remodeling, all the better to convince other investors to build those resorts. Brown built a luxurious concrete mansion on his property in the Spanish Colonial Revival style. Although he didn’t finish it before he went broke, it was quite the showcase and the town of Nice grew up around it in 1920s. It still exists and today is an upscale hotel.

The Clear Lake project began in 1906, which was Brown’s halcyon year. In the wake of the 1906 earthquake the mayor of San Francisco appointed him to the Committee of Fifty, which was supposed to guide the city through the crisis – a clear signal the movers ‘n’ shakers considered him a trustworthy man of good judgement. Also that year his bank acquired the Union National Bank on behalf of the Western Pacific Railway to handle all their financial needs. This was an old and highly esteemed bank with a reputation for being cautious.

In his mid-forties, J. Dalzell Brown might have coasted into the footnotes of history books as a distinguished banking tycoon – the vice president of two major banks, treasurer of a railroad expected of great things, a land developer with 3,000 acres of prime real estate, plus whatever he was up to in South America. Life was sweet. Then came the 1907 bank panic.

Read that two-part series for background if desired (don’t miss the part where a U.S. Senator believed someone was trying to kill him while on the Senate floor) but in brief, the banking system truly was on the edge of collapse. Most of the crisis took place in the middle of October and was contained to the East Coast and Wall Street; by the time California was impacted there were measures in place to shore up the system. Still, the governor declared a “bank holiday” for most of November and the state legislature stretched it to Christmas, all on a day-to-day basis. Few financial institutions in the Bay Area took advantage of the optional closures, preferring to stay open as a sign of confidence and solvency.

Two financial institution that did pause operations were Brown’s California Safe Deposit and Trust Company (let’s shorten that to CSD&T from here out) and Union National Bank. Nearly every day that November a San Francisco reporter would ask about the status and he always said things were going swell, that a big deposit was on its way from New York, that his staff was collecting on loans, not to worry.

Come December, all was not going so well. State Bank Commissioners demanded a clear statement of CSD&T’s status. The board at Union National announced they would need to reorganize the bank; Brown was out as VP, and they were taking back his shares. After articles began to appear about CSD&T possibly raiding a famous trust fund, there were rumors he might be planning to leave the country.

On Dec. 8, he and the bank’s attorney/fellow VP Walter J. Bartnett were arrested for embezzlement of the $205,000 Colton estate. Longtime readers might recall the trial over the Colton money was an important part of Santa Rosa history.7

CSD&T would not be reopening. For the rest of the year and into 1908, the Dalzell Brown scandal(s) dominated San Francisco newspapers – entire pages were devoted to new news, old news, quotes from victims, lawyers, banking experts and politicians. The story took off, in part, because the bank had billed itself as a place for customers with small accounts; blue collar laborers and office workers. There were over twelve thousand account holders and a third were women.

Much was also made of the legal gunfighters they hired: Brown’s lawyer was famed criminal defense attorney Hiram Johnson, who would become California governor in 1911. The attorney for co-defendant Bartnett was Santa Rosa’s Thomas Geary. But what really had newspapers flying off the racks was the reveal that Brown and other bank executives had been making investment decisions based on the advice of psychics.

When that angle of the story surfaced, CSD&T President David F. Walker and the other executives vehemently denied it was true, but later they admitted in Grand Jury testimony that yes, they had been holding seances together at their homes (they still insisted no banking advice was taken) and individually at the parlors of spiritualists Mrs. J. J. Whitney and Molly Smith.

Carrie Whitney was the grand doyenne of San Francisco’s clairvoyants, having advertised herself as a medium in classified ads since 1884.8 The San Francisco Examiner sent a reporter to ask about her dealings with the bankers, although her voluble parrot, Polly, was quoted almost as much as the woman being interviewed:

“…As long ago as last May my spirit control warned me that something was wrong with the California Safe Deposit and Trust Company…”

“Put me to bed and cover me up!” muttered Poll.

“For months Mr. Brown has been greatly worried” –

“One!” exclaimed Polly.

“for he knew the end was in sight” –

“Two, three!” counted Poll with uncanny correctness.

“and that the reckless misuse he and Mr. Walker and Mr. Bartnett had made of depositors’ funds would wreck the bank. Oh, it is easy to ride in automobiles and build mansions on an island with other folks money! Three true believers in spiritualism, such as they are, knew that punishment was certain if they failed to follow honest advice from friends in the spirit land…”

As the reporter left, the newspaper gave Polly the last word: “‘Ha! ha!’ came from the window, with unholy mirth. ‘Good-bye, good-bye, you lobster!'” The Examiner accompanied the piece with a funny cartoon of Brown standing on tippy-toes feeding a coin into a slot on the parrot’s cage as if it were a vending machine or Mechanical Turk.

(RIGHT: Illustration from the December 10, 1907 San Francisco Examiner)

(RIGHT: Illustration from the December 10, 1907 San Francisco Examiner)

Brown insisted he took not one dollar for himself, and that’s literally true – but he was a bank robber just the same. Without crawling too deeply into the weeds, he handed out “loans” that were, in essence, gifts; he swapped worthless CSD&T or Western Pacific stock for cash, or used it as collateral for real loans from other banks; he recorded fake loans to shell companies to coverup “overdrafts” which were really stolen funds; he had the books cooked to hide millions of dollars that were missing.

These were staggering financial crimes. Other CSD&T directors had not been as discreet as Brown and over $2,000,000 in 1907 dollars went to executives. Bank President Walker gave himself loans worth $750k ($24M in modern dollars) and the Treadwell brothers funneled even more than that into stock trades in companies controlled by Brown.

Here’s a few of my favorite examples of other deals:

|

Much – or maybe all – of the ambitious Lake County project was financed through Brown’s bank. He gave the company, and the developer personally, unsecured loans worth over $3.5M today

|

|

The state bank commissioner who examined and approved the CSD&T books at the end of 1906 walked away with a loan equivalent now to three-quarters of a million dollars

|

|

Former San Francisco Supervisor Charles Wesley Reed getting a $30k (now $1M) loan using four hundred mules as collateral. One editor quipped the mules must be compounding quarterly

|

Brown and his band of financial pirates knew full well this was a Ponzi Scheme and spent much effort to keep CSD&T afloat. Union National Bank was in trouble because its VP (Brown) had paid cash for lots of CSD&T stock from its vice president (Brown). Bartnett took the securities from the Colton estate to New York City and sold them at a discount, all to prop up CSD&T. While he was on the East Coast illegally peddling these stocks he communicated with Brown and the others via telegrams written in a code they dreamed up before he left. I’m sure honest bankers do this sort of thing all the time.

The scandal stayed on the front pages because no one was quite sure how much money had been stolen. The accounting was a joke; some entries were made fraudulent by crude means, such as adding a “1” to the left side of a number or changing a “3” into an “8”. Some debts and liabilities weren’t recorded at all.

Prosecutors began negotiating with Brown to turn state’s witness against his old chum, Walter Bartnett. In exchange he pleaded guilty to only embezzling $65k from a public utility and received an 18 month sentence, of which he served fifteen. (Once at San Quentin, he was given the apt prison monicker “Razzle Dazzle.”)

His Grand Jury testimony didn’t amount to much, and he divulged no treasure maps. It was reported he gave Bartnett control “at the command of the syndicate of astral bankers” and explained the codes Bartnett used in the telegrams. The press was mostly captivated that he was brought to court from prison with his “shaven head hidden under a luxurious brown wig.”

So here’s the Executive Summary: J. Dalzell Brown was a crime boss. He assembled a team of rogues who obediently followed him through five companies (three railroad, two banking) where Brown was always the treasurer. As directors the only stockholders they cared about were themselves, allowing Brown to plunder those companies of assets – some of which were used to enrich themselves with gifts of fortunes disguised as “loans.”

From 1898 to 1908 Brown’s gang was mainly Walter J. Bartnett and Treadwell brothers John and James. Bartnett was usually the front man for the companies, acting as president; the Treadwells were heirs to a famous Alaskan gold mine and their stock shares were often used as securities when Brown got involved with a new company. The three of them undoubtedly would have reprised those roles for the Ramona and Bonita oil companies, had not they been under indictment at the time for acts of fraud committed while they were directors of the banks controlled by Brown.9

In their place, Brown tapped new players to be the public face of the Petaluma oil ventures: Norton C. Wells, Charles Gregg and Cassius Webb, who were introduced in part I. None of them were who they said to be.

Gregg replaced Bartnett as Brown’s front man, named president for Ramona and Bonita and VP for another Petaluma oil operation. Although the Petaluma Argus had reported “it is an open secret that Mr. Gregg…is in reality the chief of the fuel department of the Western Pacific Railway Company” he had no connection with the railroad. It later came out that Gregg was a San Francisco crony of Brown, who had transferred to him 1,000 shares of the railroad’s stock as he was about to begin his prison sentence – stock, which by the way, actually belonged to Brown’s wife, Harriet.10

Norton C. Wells was the other man named as an owner of the Bonita and Ramona oil companies, as well as both project manager and a “heavy stockholder.” He was directly involved in the California Safe Deposit & Trust fraud as branch manager of the Fillmore office, which is where many of the phony loans were issued. The San Francisco papers noted prosecutors briefly considered indicting him alongside Bartnett and the Treadwells.

Of all the characters involved in the Petaluma oil saga, Cassius M. Webb was the only one who had any actual experience in the business. Yet it’s a mystery why he told our local newspapers he was the lawyer for Ramona and Bonita Oil, since no evidence can be found that he was an attorney at all. Elsewhere he was called a “promoter,” “western mining expert,” and that great catchall for any fellow who didn’t have a real job, a “capitalist.” In the 1900 and 1910 census reports he identified himself as a mining engineer. He apparently was brought into the Petaluma oil because he was a “lifelong friend” of Gregg.

Yes, we were lucky that Brown and his slippery trio didn’t hit oil here and use it to start another stock scam, but that doesn’t mean Petaluma came away unharmed.

At the exact same time the Consolidated deal was in a nose dive, Webb and Gregg were being sued in Kern county for fraud, having sold an oilfield that was later discovered to have been obviously salted. The suit was dropped, apparently because the company didn’t want to risk looking like idiots – bad publicity and a stockholder backlash would likely follow should it become widely known they were so easily swindled. The Petaluma Argus remarked the news about the suit caused “a genuine sensation” because the Webbs lived in town and “quite a number of local people have purchased the stock in question.”11 Soon thereafter Webb and his wife moved to the East Coast.

1 John W. Frank testimony reported in the Petaluma Daily Courier, December 22, 1911 |

2 “Promotion stock” was a term back then for shares awarded to company principals and key employees in lieu of salary or other payment. It was notoriously misused in oil company scams because the shares could be flipped immediately, leading many businesses that were seeking to appear legitimate to prominently advertise they had “no promotion stock.” |

3 In his letter to Ramona stockholders, John Frank said he and superintendent McDonald were later able to reactivate the Ramona well to its original capacity. |

4 Petaluma Argus, April 28 1910 |

5 In 1910, ten shillings was worth $2.43. Par value of Ramona and Bonita stock was 25¢ at the time. (Converting from 1910 to today’s values, 10s would now be worth the equivalent of about $70, and 25¢ would be worth over eight dollars.) |

| 6 The Alameda & San Joaquin Railroad was incorporated in 1898 and the Stockton & Beckwith Pass Railroad, 1902. |

7 As detailed here previously, a high-profile court case brought by Ellen Colton, the widow of a railroad exec, was such a political hot potato no court in San Francisco would touch it. The bench trial was moved here and lasted almost two years between 1883-4, bringing so much cash into town it spurred a downtown building boom. The Athenaeum, which was the second largest theater in the state, and new 2-3 story brick buildings on Fourth Street made us look like a proper Victorian America town, although most of those masonry buildings would crumble in the Great Earthquake. |

| 6 At the time of Brown’s thievery, all papers had a classified ad section for clairvoyants, spiritualists, palm readers, etc. My personal favorites from 1907 were “Ora the Wonder” and “Byron Stanley, A Man of Strange Power.” |

9 Bartnett was found guilty in 1908 of misappropriation and embezzlement of securities; he was sentenced to ten years but his conviction was overturned on appeal. James Treadwell was indicted on multiple charges of complicity with Brown and Bartnett but was acquitted in 1909 by a jury. |

10 Affidavit of Benjamin A. Judd, February 1909 and San Francisco Examiner, November 6 1910 |

11 Petaluma Argus, December 24 and December 28 1910 |

Title image: The oil derrick shown is unidentified, but it’s probably the Ramona well. Photo courtesy Petaluma Historical Library & Museum

I am returning you herewith papers in the matter of the Consolidated Oil Fields of California, Limited.I am sorry that I cannot tell you more as to the actual value of this property, but our work has not, so far, taken us into this district, and the writer is not personally familiar with the ground. A Bureau representative, however, who is thoroughly familiar with the field, says that while the territory shows some indications of oil, the geological structure is very much broken, and there is little or no chance for any extended field or large production.

Some of the statements made in the report of Cassius M. Webb appear to be true; others are entirely ridiculous. I believe that the possible output of the Ramona gas well is greatly exaggerated, and doubt whether it has any commercial value. As to the producing power of the Bonita well, we have no information, but I can see no reason why this well should not be pumping if actually a producer. As to the land being proven, this of course, is absurd. The value of any part of this territory is highly doubtful.

It is a fact that the property is well located, and if it should prove to be oil land would be of considerable value, but at present is a rank wild-cat, and as such is greatly overcapitalized. Such statements as that of Mr. Webb that the property could be put on a dividend paying basis in sixty days, if it were possible to secure a drilling rig, can be intended to deceive the most ignorant. Complete rigs can at any time be had on telegraphic order at four points in the state, and even if every well they drill should prove successful, it would require considerable time to put the property in paying condition. The statement made in both the report and the advertisement bear all the earmarks of deliberate fraud. Very truly yours, PAUL W. PRUTZMAN, Field Assistant California State Mining Bureau.

– Petaluma Argus, September 10 1910

ENGLISHMEN COMING HERE

The publication exclusively in the Argus on Saturday of the article from the San Francisco News Letter relative to the local Oil Fields, in which the last named publication branded the local fields as valueless and the Consolidated Oil Fields of California as a “rank scheme” created a great sensation in this city. There had been much speculation and so many rumors in circulation as to the authenticity of the oil strike that the article in question, having the backing of the State Mining bureau, proved to be about the worst blow yet delivered at the men who have staked their reputations and their money on finding oil in paying quantities in this vicinity.

General Manager Frank of the Consolidated Oil Fields of California, Limited, was in the city on Sunday and sought an interview with the Argus. Mr. Frank was not in the least perturbed by the publication of the article in the News Letter. His only regret was that the author of the article did not seek definite information, such as could have been secured by a visit to the local fields, before branding his company a “wild cat” scheme and the local oil fields as barren in so far as oil in quantities is concerned.

Both Mr. Gardner and Mr. Prutzman, the former declaring that “this is about the rankest fraud yet,” are without definite information upon which to base their conclusions. Neither has visited the local fields and they appear to have “jumped” at their conclusions.

Mr. Frank informed the Argus that, regardless of the criticism of the people and the press, the work of exploiting the local fields will continue. He was one of the first experts to visit this field and has from the first been convinced that oil of high grade would be found here. He is now more than ever convinced that such is the case by reason of the strike in the present well and expresses the belief that before many days his opinion will be further substantiated by the development of the well.

Opinions of scientists differ as to the nature of the local fields. Some of the state mining bureau experts declare that the field is so broken that it is not possible for large deposits of oil to exist in it. Others declare that the contrary is true and that the indications are more favorable here than in any other part of the state for finding oil in large quantities. Mr. Frank is of the latter class and is backing his judgement.

At the time the English Syndicate was formed the officers of the company gave Mr. Frank his choice of fields, either in northern or central California. Mr. Frank chose the local fields for development by English capital because he believed the prospects here were better than anywhere else. The result is that the company has undertaken to develop the local fields and will continue to do so until oil in paying quantities is found in other wells than the one now being drilled and which is already in oil.

“Some people have gone so far,” said Mr. Frank, “as to express the belief that we salted this well – that we poured the oil down the pipe. Why, I would like to know, should we do such a thing? Our company has no stock for sale. We are not selling stock either here or in London. We have nothing to unload. The English stockholders have every confidence in the success of our development work. There is no reason under the Heavens why we should resort to any tricks in the prosecution of the work of developing the Petaluma fields and we have not done so.”

The stock of the Consolidated Oil Fields of California, Limited, is listed on the London Stock Market at par, $2.50 per share. It is thereby given a standing with other and similar stocks that speaks well for the standing, of the promoters over on the other side of the pond. The president of the company is now enroute to California and, with Major West, will probably visit this city during the present month. By that time Mr. Frank hopes to have the new well on the pump and producing at the least several hundred barrels dally. All the holders of Ramona and Bonita stock have been protected by the new company. Mr. Frank has issued $206,000 of stock in the English syndicate in exchange for an equal amount of stock in the old companies. Additional proof of the genuineness of the oil strike here is shown by the fact that Mr. M’Donald and Mr. Travis just recently refused to dispose of their lease of the Miller ranch for a large sum of money. These men are in a position to know the value of the local fields. During the past few days a number of leases in the local fields have been sold to local people who every confidence in the future of this section as an oil producer.

[..]

– Petaluma Argus, September 12 1910

WESTERN PACIFIC STOCK IS DIVIDED

Startling Testimony Is Given Against Directors of Defunct Bank.SAN FRANCISCO, Dec, 23. J. W. Frank, an oil expert of Oakland, made a startling disclosure yesterday at the examination being conducted by Attorney Samuel Rosenheim in the suit for accounting brought by the depositors of the wrecked California Safe Deposit and Trust company against the directors of that institution. Frank gave direct evidence of the division of 50,000 shares of Western Pacific stock among four of the bank directors.

This information, which Rosenheim only recently learned of, came as a complete surprise to Attorneys James A. Cooper and Frank H. Powers, representing several of the directors.

This was shown on the cross-examination where Cooper, who is the attorney representing Defendant Bartnett in this action, asked Frank if Brown had told him how many shares Hiram Johnson had received of the Western Pacific in the division of those securities. The witness replied that he had not been told by any one that Johnson had been given any shares.

Continuing his testimony, Frank said that on the trip to Mexico, which concerned an oil venture at Mazatlan, J. Dalzell Brown said that for the terminal facilities at Oakland the Western Pacific put up 50,000 shares of stock. This stock was divided into four equal portions of 12,500 shares, and Bartnett. Dalzell Brown, James Treadwell and John Treadwell shared it among themselves.

RELATES DEALINGS.

Frank related his dealings with C. W. Gregg in trying to negotiate a loan on 1000 shares of Western Pacific stock to get funds to develop oil properties in Petaluma and Pleasanton. Frank was in Denver at the time, and letters and telegrams that passed were read. Finally Frank went to Red Bluff, where the 1000 shares of Western Pacific stock reached him by express. The stock was then worth about $25,000 or $30,000. Frank tried to get a loan of $15,000 from W. R. Cahoone of the Bank of Tehama at Red Bluff. After considering the proposition. Cahoone finally declined to make the loan, on the ground that the stock was not listed on the Stock Exchange. The stock he offered for a loan, witness testified, belonged to Brown.

Subsequently a letter was received from J. Dalzell Brown saying that Mrs. Brown had put up securities to the value of $30,000 to promote the oil schemes. In a postscript to this typewritten letter Brown, who was then under sentence of imprisonment, in a hand which bore evidence of writers’ cramp, had written with the pen: “On my release it is my intention to devote my entire time and energy to the oil business, and I join with you in the wish and hope that we may make lots of ‘easy clean money’ together. J. D. B.”

– Oakland Tribune, December 23, 1911

BANK WRECKER WOULD BE KING

Aim of Dalzell Brown Alleged to Be Rulership of Opera Bouffe Principality.

Secret of His Desire to Be Consul for Uruguay Explained – Frenzied financier Sought Station as Grandee of Latin AmericaSan Francisco – Last week the Republic of Uruguay appointed as its consul in San Francisco Dalzell Brown the frenzied financier who is supposed to be responsible for the wrecking of the California Safe Deposit and Trust Company. The secret of Brown’s desire to represent Uruguay in San Francisco was explained when a former associate of the banker asserted that Brown had visions of vast South American estates with himself as the greatest grandee of the western hemisphere. In fact, Brown already had made some progress toward the realization of his dream for he had persuaded many leaders in the Central and South American countries to deposit their money in his bank. He succeeded in gaining their friendship, and among the names of the depositors will be found those of several hundred Latin Americans. Among them was Juan Moisant, the well-known plantation owner of Salvador, who between the Central American government and Dalzell Brown has lost during the past six months the greater part of his immense fortune.

Brown sent alluring notices to all the representatives of the Central and South American countries in San Francisco and through them had gained many clients for his bank. Brown finally conceived the idea that he could achieve better results if he himself were duly accredited as the consul for Uruguay at this port. Uruguay is small and not very particular, and Brown got the job. He didn’t get it soon enough, however, to put it to any use in furthering his plans for the vast empire of which he dreamed.

Brown gained most of his knowledge of South and Central America from the comic operas where gracious promoters merge a couple of republics, purchase the army, double the capital stock and float the concern in Wall street. Brown had planned an empire of the sort that King Leopold of Belgium created in the Congo. He had figured it all out – how the rubber, the bananas and timber interests would yield him a revenue which would make possible a mansion that would make the Lakeport residence look like a porter’s lodge.

Brown showed great interest in the Moisant plantations at Santa Emilia, and had given some consideration to their purchase. With this as a base he proposed to extend his holdings until they formed a domain without rival on the globe.

In his office Brown kept a number of maps of the tropical countries, and these were among the effects seized by the corps of detectives who forced his desk at the bank building. One of them was of a rubber plantation which has secured a number of stockholders in San Francisco.

Some of literature dealt with sugar plantations but no matter what the enterprise Brown was always sure, as was Colonel Sellers, that there were “millions in it.”

– San Francisco Call, December 26 1907

The Central Counties Land Company Bubble

Of all the paper projects and promotion schemes which had after repeated failures made Lake county water development and railroads a byword, probably the most sensational was that of the Central Counties Land Company, which absorbed the county’s interest in 1906 and 1907. This was one of the activities of J. Dalzell Brown, who was sentenced in April, 1908, to San Quentin penitentiary for eighteen months for his part in wrecking the California Safe Deposit and Trust Co. Lake county people received much of the money of the depositors in that wrecked institution.

The most widely advertised part of the Central Counties Land Company’s project was the construction of a boulevard entirely around the circumference of Clear lake, a distance of eighty miles. One unit of this, a 2000-foot wooden trestle bridge across an arm of the northern end of the lake, was completed in September, 1907, at a cost of $12,000. Brown had a splendid concrete mansion built on the northeast shore at a cost of $60,000. The Hotel Benvenue in Lakeport was bought and luxuriously furnished, principally for the use of Brown and his associates when in the town. Underlying these frills was the plan to acquire the lake waters for power and irrigation purposes…

– History of Mendocino and Lake Counties, California, 1914, pg. 148

COMMISSIONER BLAMED FOR BANK FAILURE

Prosecution in Brown-Dalzell Case Flays Book Inspector.

CARELESSNESS IS ALLEGED

Commissioner Dunsmoor Could Have Averted Crash.

DID NOT REQUIRE THE OATH

New Developments in Failure of California Safe Deposit and Trust Co.Hearst News Service

SAN FRANCISCO, Jan. 8. — Former Bank Commissioner Charles Dunsmoor was flayed today by Prosecutor Cook and Herman Silver, president of the bank commission, who declared that the failure of the California Safe Deposit and Trust Company might have been averted if he had performed his duty when he made an examination of the books of the wrecked bank with Commissioner Currier in December, 1906.

According to Prosecutor Cook, the carelessness of Dunsmoor is alone responsible for the failure of the District Attorney’s office to have indicted for perjury John Dalzell Robertson [foster brother of J. Dalzell Brown], secretary of the bank, who fled from the city immediately after the failure.

“When Dunsmoor made his examination of the bank with Commissioner Currier he made no effort to have Robertson swear that the entries which appeared on the books were authentic,” said Cook. “Dunsmoor and Currier counted the cash in the bank on the afternoon of December 3. The books were falsified over night and Dunsmoor and Currier drew up their report on the following day. They dated their report December 4 and made no effort to put the customary oath to Robertson until December 6. Robertson then swore that he was willing to answer truthfully any questions that would be put to him. No questions were put, for the report had been already drawn up and signed by Dunsmoor. The whole thing was farcical. Robertson should have been sworn before the examination of the bank began. As it is, the carelessness of Dunsmoor. who was in charge of the examination, will prevent us from indicting Robertson for perjury.”

The customary oath administered to officers when a bank is examined pledges them to answer all questions concerning the character and value of its assets and the amount of its liabilities.

“I will in no respect misrepresent or conceal anything relative to the true condition of the bank” part of the oath reads.

As Robertson did not take this oath until after the examination of the bank was completed however, its entire value was negated.

Prior to sending his resignation as president of the bank commission to Governor Gillett, Silver called on Prosecutor Cook and declared that the report on the condition of the bank signed by Dunsmoor in 1906 showed that the attention of the Governor should have been immediately attracted to it.

With deposits aggregating $7,765,000, the report showed that the bank had only $169,174.06 of cash on hand.

“This showing was enough to indicate that the persons associated in the management of the bank were treading on very dangerous ground,” said Silver. “I cannot understand why the Governor’s attention was not called to the bank at this time. The carelessness of Dunsmoor appears inexcusable.”

Examination of th© secret correspondence recovered from the vaults of the bank by Prosecutor Cook has resulted in the additional disclosure that all of the larger loans made to the corporations dominated by James Treadwell were mythical. According to Cook the money never left the bank and the loans were entered on the books to cover overdrafts and to inflate the paper showing of the assets of the institution.

Cook’s examination of the accounts of the hank disclose the fact that over $2,000,000 of the depositors’ money was personally loaned to Bartnett, Brown, Treadwell and other executive officers of the company on mythical security.

The Carnegie Brick and Pottery Company is listed for a loan of $150,000 on October 28. The El Dorado Lumber Company has a loan of $250,000 entered against its name on the same date. Another loan of $200,000 is represented on the books of the bank as having been advanced to the San Francisco and San Joaquin Coal Company.

“None of this money ever left the bank,” said Prosecutor Cook. “The loans were fictitious so far as the companies were concerned and were entered on the books of the bank merely to cover up overdrafts of the executive officers.”

Brown, Bartnett and Treadwell appeared before Superior Judge Dunne this morning to answer the indictments returned against them by the Grand Jury. The proceedings took up half an hour, which was given almost entirely to the reading of the bills. By the consent of the prosecution and the defense the cases of Brown and Bartnett were continued until January 16 for argument and that of Treadwell until January 15.

– San Jose Times Star, January 9 1908