It was a momentous day: On February 24, 1854, the state legislature was gathered in Benicia to vote on moving the state capitol to Sacramento. Three assemblyman stood and proposed to choose their own county seat instead – one wanted Marysville, another Stockton. James Bennett suggested Santa Rosa before the Yolo legislator rose and asked: “What county is Santa Rosa in?”

Oh, snap!

See, Santa Rosa wasn’t the Sonoma county seat at the time. In fact, Santa Rosa didn’t really exist. It had only two houses and five little businesses, including a tavern. Yet despite its drawback of being almost non-existent, Bennett and other men were about to make it the centerpiece of the county.

When Santa Rosa was celebrating the Centennial Fourth of July in 1876, an article about Santa Rosa’s founding appeared in the local Sonoma Democrat newspaper. It was unsigned but was clearly written by someone who was here during 1851-1854, which were the years being described. It’s a key reference; traces of it pop up in every regional history. But aside from a Gaye LeBaron column published four decades ago, the bulk of the piece hasn’t appeared anywhere over the last 140 years. It can be found transcribed below.

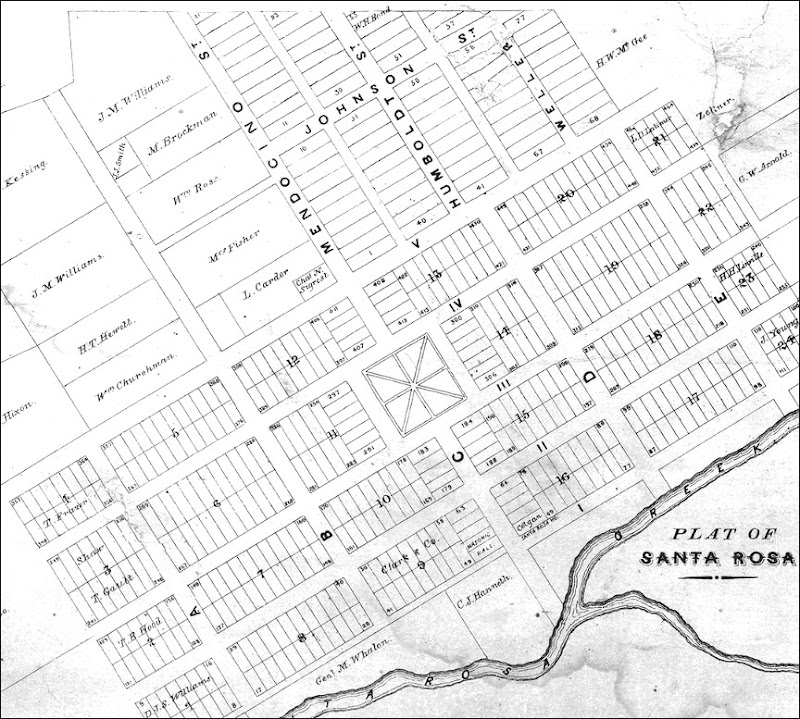

(RIGHT: Detail from 1866 Map Of Sonoma County)

(RIGHT: Detail from 1866 Map Of Sonoma County)

That article covered the birth of Santa Rosa, death of Franklin (a village near the Carrillo adobe) and the campaign to capture the county seat. It was surprisingly slim on the particulars of those notable events. Instead, the value of this piece lies in its first-hand descriptions – such as Squire Coulter rolling his building from Franklin to Santa Rosa on wheels. Other buildings, including the Baptist church, likewise rolled away from Franklin over the following months, in what must have been a very odd and very slow procession. The author also described the Carrillo homestead as the main commercial center north of the town of Sonoma, a “lively spot” where “almost every day pack trains and wagons from the Russian river and the neighboring country surrounded the old adobe.”

Mostly the item described who was there and what they did. Personally, I’m not much interested in who was the first blacksmith in Santa Rosa and where his shop stood, but details of that sort can give genealogists a case of the vapors. For more information on the people mentioned there – including correct/alternate spelling of some names – refer to pages 20-22 of “Santa Rosa: A Nineteenth Century Town” by LeBaron et. al.

Left unanswered in the article about the early 1850s – and not discussed in any local history that chronicles those years – was a key question: Why did Santa Rosa come to exist?

The old item from the paper explained how the story ends: There was a vote over the county seat in Sept. 1854 and Santa Rosa won over Sonoma, 716-563. Historians credit the victory to the blowout Fourth of July party thrown by Julio Carrillo and the other Santa Rosa promoters, which “invited to the feast the rich and poor, the lame, the halt and the blind – in fact everybody who had, or who could influence or control, a vote,” according to historian Robert Thompson. An estimated 500 showed up to eat barbecue and dance until dawn, apparently going away with full bellies and warm feelings about the potential of Santa Rosa as the new county seat, in spite of the town only having added two houses over the previous year, bringing the grand total up to four. (One of those new houses was the Masonic Lodge, built at great expense because they shipped in East Coast pine, as no one was yet sure if redwood would be good for construction.)

But events leading up to the vote are sketchy. That’s not particularly surprising; much of California history between 1850-1855 is full of gaps. Even in Sonoma county it’s hard to peg down what was happening year to year. There’s no doubt, however, that nearly everyone, Californio or American, rich or poor, was fretful over keeping their property. Should you build a cabin and plant crops if you could be kicked out before the harvest? Would the ranch supporting your family be taken away by the government, or taken over by squatters?

Once California became a state, no one – no one – was happy with the situation over Spanish/Mexican land grants. In theory, anyone who had land under Mexico simply had to provide documentation to claim ownership under statehood. In practice, the system set up by the U.S. to settle ownership issues was the worst possible, leading some properties to remain in limbo for over twenty years.

The Yulupa rancho east of Cotati was a good example; although Jasper O’Farrell had surveyed the surrounding ranchos, Yulupa specifically had no survey of its own, so the government rejected the claim in 1854. Appealed to federal District Court, the claim was approved in 1857. Two years later it was rejected again, this time by the U.S. Supreme Court. Not until 1865 was that large chunk of central Sonoma county (about 25 square miles) legally available for ownership. Squatters, of course, had been living and farming on that land for years.

The legions of settlers pouring into California expected to find the same encouraging homesteading policies followed elsewhere in the rest of the West – that anyone who could throw together a shack on public land could declare it as their own, paying the government little or nothing. But because the grants covered nearly all of Sonoma county, there was no public land. “The whole County is claimed. There is not a foot of ground that will do to cultivate but what is claimed,” complained a new arrival in 1853 to his family in Kentucky. “…We cannot tell anything how they will go.”1

Some settlers leased acreage or had other arrangements with the grant holders, but others squatted without permission. Twice confrontations with armed bands of squatters nearly came to shooting wars – near Healdsburg where a deputy sheriff was killed, and near Bodega where the rancho owner recruited a gang of toughs from San Francisco in an attempt to drive them off.

The state legislature fielded various proposals to mollify settlers, such as considering giving then 160 or 320 acres of public land somewhere else in the state or requiring grant holders to pay evicted squatters for what they had “cultivated or improved,” the value to be set by a jury specifically composed of other settlers. Meanwhile, the Mexican grantholders – usually land-rich but cash-poor – were being bled dry by legal fees defending their claim. To raise funds they usually sold off parts of the rancho to settlers or speculators, even though those sales would be invalid if the courts didn’t eventually validate the Mexican grant. Did I mention no one was happy with the situation?

“Settler’s rights” became a political rallying cry all over the state, and nowhere louder than Sonoma county. Before the state election of 1853, there was a settler’s convention here independent of the Democratic or Whig parties and they nominated for the Assembly one James N. Bennett, a recently-arrived squatter living near or just outside rancho Yulupa (named for him is Bennett Valley and Bennett Peak). Bennett won the election by just 13 ballots amid charges there were “importation of voters.”2

Bennett was a single-term assemblyman. Besides asking the legislature to move the state capitol to Santa Rosa in 1854, his only legacy was passage the following month of “An Act to locate the county seat of Sonoma anew.” According to the Sonoma newspaper, the proposal came as a surprise to the town:

The first intimation we had of the people’s desire to move the county seat from Sonoma to Santa Rosa was through the legislative proceedings of March 28, which inform us that a bill had been introduced and passed for that purpose. From what source did our representatives derive the information that a change was demanded by our people? In the name of a large body of their constituents we protest against the measure as premature, unauthorized and impolitic. The county cannot even repair the miserable building, and the only one it possesses; how then can it bear the expense of erecting new ones? |

That “miserable building” was the county courthouse, and had earlier been condemned by a grand jury, which called it “an old dilapidated adobe of small dimensions, in part roofless and unfit for a cattle shed.” They say it had cost $9,000, of which $3,000 had been paid and $6,000 was still claimed. The town paper – unaware that a plot was afoot to move the county seat – commented at the time, “the old court-house is about being deserted, and high time it should be, unless our worthy officers of the law would run the risk of being crushed beneath a mass of mud and shingles, for we really believe it will cave in the next heavy rain.”

Clearly some measures had to be taken by the county to provide a useable courthouse, but a seat of government usually doesn’t pack up whenever a building needs repairs. Not only did Bennett’s “Act to locate the county seat of Sonoma anew” propose exactly that, but its language was crafted to specifically fit Santa Rosa: “…said location shall be as near the geographical centre of the valley portion, or agricultural portion of said county, as practicable.”

But the county residents, I believe, saw it as something more than just voting on moving the courthouse to Santa Rosa – and the tipoff is that part of the Act regarding the importance of the new seat being at the center of the county’s agricultural region. There is clearly no need for the county seat to be in the middle of the farmland, but in 1854 Sonoma county, that meant being at the center of local squatter activity, and the horseback ride to the courthouse in Sonoma took at least two hours, each way. It was, essentially, declaring the county to be welcoming to squatters while being also a gesture of defiance against both state and nation for their failure to “solve” the land grant problems to the settler’s liking.

That is, I’ll grant, just my reading of events. We don’t know the content of speeches made at the Fourth of July BBQ, which probably declared what Bennett and others were really after. But “up-county” (as the Sonoma paper called areas north of them) certainly had more small farmers likely to be very upset about the indecisive, snail-paced processing of the grant claims. Aside from a couple of tiny districts, Sonoma and Petaluma were the only places that voted against the move.

And moving the county seat was only the first of Sonoma county’s many contrarian positions in that era. In the 1855 elections there was a local “settler’s ticket” where every single candidate won. The county remained out of step with the rest of the state a few years later as the Civil War began, being the only most significant county in California that never voted for Lincoln. And in the center of it all was Santa Rosa, a town created from nothing.

Which brings us back to that big question: Why did Santa Rosa come to exist? Towns usually evolved organically around something like a trading post, a riverport, a stagecoach or railroad stop. Maybe there was an adjacent swift-moving waterway to power a mill or factory; maybe there was a mine which employs lots of miners. The only apparent advantage of Santa Rosa’s location was that it was at a crossroads, although to date that had not provided enough incentive for anyone to build a house or store there. Ignored in every published history, however, was the significance of this: The town was pressed tightly against the side of a very old Pomo village.

Kabetciuwa was a large and significant community, extending the equivalent of two blocks along the bank of Santa Rosa Creek from modern-day Santa Rosa Ave. to E street. (There was also another village about a mile west called Hukabetawi, in the vicinity of where W Third St. meets N Dutton Ave.) Whether any Pomo families still lived at Kabetciuwa in 1853 is unknown; about fifteen years prior smallpox epidemics decimated the population, and from later accounts we know many survivors regrouped near Sebastopol and Dry Creek.

Perhaps Santa Rosa was at that particular spot in order to exploit those Indians who remained as laborers; certainly over their centuries of living there the Pomo would have developed the best possible ways to access the confluence of Matanzas Creek and Santa Rosa Creek, which would be an advantage to residents of the new town. Today, sadly, Kabetciuwa has been completely obliterated by Santa Rosa’s city hall complex and the federal building. Our squatter forefathers would be so proud of how the city they created just took a place over without so much as a look back.

1 James Jewell Letters 1853, cited in “Oliver Beaulieu and the town of Franklin” by Kim Diehl, 1999, pg. 6

2 “Fighting Joe” Hooker, California Historical Society Quarterly v. 16, 1937, p. 307

|

| Santa Rosa as shown on A.B. Bowers wallmap of 1866 |

SANTA ROSA–CONDENSED SKETCH OF ITS EARLY HISTORYIn 1851 there were but three houses in the vicinity of Santa Rosa and none upon the present site of the town. The old Carrillo house on Santa Rosa creek, distant about a mile, was built in 1838 or 1839. Then came another adobe house on the Hanneth place which still stands, and then the Boileau House now owned and occupied by Dr. Simms, formerly the property of John Lucas. This house was build in the summer of 1851.

In January 1852, A. Meacham, now of Mark West, was keeping store at the old adobe, on the Carrillo place, now owned by F. H. Hahman. Hoen, Hahman and Hartman succeeded to the business of Meacham. For the next year the old adobe was a lively spot and these pioneer merchants drove a brisk trade. There was no other store north of Sonoma, and almost every day pack trains and wagons from the Russian river and the neighboring country surrounded the old adobe.

In the summer of 1853, the question of the removal of the county seat from the town of Sonoma to a more central locality was agitated. A town was laid off at what was then the junction of the Bodega, Russian river and Sonoma roads, just where the cemetery lane unites with the Sonoma road, near the eastern boundary of the city. Dr. J. F. Boyce and S. G. Clark built and opened a store there. Soon after, J. W. Ball built a tavern and a small store. H. Beaver opened a blacksmith shop, C. C. Morehouse, a wagon shop, W. B. Birch, a saddle-tree factory.

In September, 1853, S. T. Coulter and W. H. McClure bought out the business of Boyce and Clark. The same year the Baptist church was built, free for all denominations. Thus early was liberality in religious matters established on the borders of Santa Rosa, and happily it continues down to this day. The only two dwellings were owned by S. T. Coulter and H. Beaver.

Franklin town had now touched the high tide of its prosperity, and was destined to fall before a more promising rival which, up to this time had cut no figure in the possibilities of the future.

In 1852, John Bailiff built on the bank of Santa Rosa creek, for Julio Carrillo, the house now owned and occupied by James P. Clark. Soon after, Achilles Richardson built a store and residence between the Carrillo house and the creek near where the iron bridge now is. This house was afterwards burned. Mrs. Valley built a dwelling house on the corner of second and D streets. The old Masonic Hall, was built in the fall of 1853. E. P. Colgan who had been at the old adobe keeping a public house, moved to Santa Rosa, and rented the lower part of the Masonic Hall, and commenced building a house on the opposite side of the street which was the first hotel and was known as the Santa Rosa House. Ball moved down from Franklin and built a blacksmith on Second street now used as a barn next to the lot of John Richards, and soon after built a dwelling on the south side of Second street, just east of Main or C street. Hahman, Harman and Hoen, in the spring of 1854 built a store on the corner of C and Second street and moved to Santa Rosa in July of that year. The building now occupied by Moxon’s variety store.

Hahman and Hartman bought of A. Meacham, 80 acres of land the west line of which ran through the plaza, paying therefor $20 an acre. They in conjunction with Julio Carrillo, laid off the town and donated the plaza to the County of Sonoma. The town limits embraced the space including between First and Fifth streets from south to north, and between A and E streets from west to east, the survey [illegible microfilm line] A man named Miller started a store in the building now occupied as the Eureka barber shop on the south east corner of second and C streets. It was managed by W. B. Atterbury.

In the fall of 1853, the election for members of the Legislature hinged on the removal of the county seat from Sonoma to Santa Rosa. Col. now General Jo Hooker, was a candidate, and opposed removal; James N. Bennett favored removal; at the election a tie vote was cast. Another election was ordered and Hooker was beaten by a few votes. Bennett introduced and caused to be passed, a bill authorizing the people to vote on the question of a removal of the county seat at the general election in the fall of 1854.

On the Fourth of July, 1854, the people gathered to Santa Rosa from all parts of the county to a grand barbacue [sic] which was held on the ground now owned and occupied by H. T. Hewitt. A Guerny, a Baptist preacher, was the orator of the day. John Robinson, Sylvester Ballou and Joe Neville also spoke on the occasion. Four or five hundred persons were present and the exercises closed with a grand ball at the new store. It was claimed by the people of Sonoma that the Santa Rosans made good use of the time and expenditures incurred, in electioneering for the removal of the county seat.

Be that as it may they won the fight, and in the fall of 1854 the county offices with the archives were transfered to the new capital. The first court convened in Julio Carrillo’s house. Soon after, a temporary court-house was built where Ringo’s grocery store now stands, on Fourth street, opposite the north-east corner of the plaza.

After the election Franklin town was removed to Santa Rosa. S. T. Coulter hauled his building here on wheels, set it down where the Santa Rosa Savings bank stands, purchasing there 80 feet front for the sum of one dollar front foot–$80 for two lots. The Baptist church came soon after and was re-located on Third street, near D. A few years ago it was turned broadside to the street and converted into two tennement [sic] houses.

Henry Beaver was the first blacksmith in Santa Rosa. His shop was near the bridge were Bill Smith’s shop now stands, on the east side of C street. Beaver purchased two acres of land and built a residence on the place now owned by Capt. J. M. Williams, on Mendocino street, opposite the Episcopal church. Julio Carrillo started the first livery stable. The Eureka Hotel was built on the site of the Kessing Hotel by J. M. Case and W. R. O. Howell. Obe Ripito and Jim Wilson built a livery stable where the Grand Hotel now stands, on the south-east corner of Third and C streets.

John Ingram built the first brick house in Santa Rosa. It was one story, situated on Exchange street, adjoining the DEMOCRAT office, and is now owned by Gus Kohle. The next brick built is owned and occupied by the pioneer mercantile firm of Wise & Goldfish.

There are but few now in the city who lived here when the county seat was removed. Among those we can recall are Julio Carrillo, Joe Richerson, Ike Rippeto, S. T. Coulter, F. G. Hahman, Dr. J. F. Boyce and W. B. Atterbury. Dr. Boyce was the first physician in Santa Rosa, and Judge J. Temple and the late Col. William Ross were the first attorneys.

The first public school was kept by W. M. Williamson, now a resident of the Navagator Islands, [sic – now known as Samoan Islands] and a former subject of Ex King Steinberger of Samoa. The first bridge over Santa Rosa creek was built by Charles White. The first church built in the town was the Christian Church, which stood on the corner of B and Fourth streets where the Occidental Hotel now stands.

F. H. Hahman was the first Postmaster. One of the first children born here now living, was C. A. Coulter, on the 12th of December 1854.

Want of space prevents our going more into detail or further along in the history of Santa Rosa. From 1856 to 1870 the town grew slowly. At the national census in the last named year it was credited with but 900 inhabitants. In 1872 the railroad was completed from tide water to Santa Rosa, and since that time the town has increased from a population of one thousand, to nearly five thousand.

Two flourishing colleges have been founded. The city limits embrace an area of one and a half miles square. There are more than 1,000 houses and there is a rapid growth in material prosperity as well as in population. The future we will not predict. We are thankful that our lot is cast in a land so fair, a climate so salubrious, a soil so fruitful that it laughs with plenty if “tickled with a hoe.”

A zealous priest, Father Amoroso, gave the stream and valley the name of Santa Rosa–in honor of Santa Rosa de Lima. The 26th day of August is her festival, and it must have been on that day that the good father discovered and baptized the stream.

[…Two paragraphs on Santa Rosa de Lima…]

– Sonoma Democrat, July 8, 1876