Imagine if the Golden Gate Bridge was never built – engineering issues couldn’t be solved, perhaps, or maybe there were insurmountable economic hurdles, or just not enough political will. What would Sonoma County be like today?

The only way to get here from San Francisco is by ferry, for starters, so Santa Rosa is a much smaller place. There was no population boom after World War Two; it’s a rural county seat somewhat like Ukiah, and the courthouse is still in Courthouse Square because they patched up the mostly cosmetic damage from the 1957 earthquake instead of tearing it down. Stony Point Road is the Highway 101 bypass, its two lanes swelling to three at the stoplights where there is cross traffic and turn lanes. Tourists clog the Redwood Highway on weekends because the winery events, resorts, spas and casinos in the countryside make this a popular getaway destination for the rest of the Bay Area, while the weekly Press Democrat is always pushing for year-round motocross and horse racing at the fairgrounds in order to draw visitors downtown. “Sonoma County? Sure, it’s a nice place to visit, but no, I…”

Building the bridge was never a sure thing, but it wasn’t because there was formidable opposition. Yes, there were efforts to slow or stop the project but it wasn’t ongoing, popping up only when the project neared a funding or construction milestone. None of those challenges posed serious threats, but were more like pesky nuisances.

Yet when the project launched in 1923 it seemed delusional to believe it would ever pass beyond the blueprint stage. Not only were there some engineers who thought it was folly to attempt constructing the longest bridge of its kind at that particular place, but its promoters had to run an incredibly complex political gauntlet, convincing Washington and Sacramento to back it enthusiastically – all before doing the basic studies which would prove the concept was viable. And even after construction began in January 1933, a retired geologist made a splash by predicting the south end could never be made stable, requiring months of further testing to prove him wrong.

All in all, it took almost 20 years to get to ribbon-cutting day. This is not the place to tell that whole story; the Golden Gate Bridge District has history pages for further details on the critical years of 1928 and 1930 (although some of the information on bridge opponents is wrong). A version of the original 1916 article proposing the idea is transcribed below.

Local folks probably know that the key part of the origin story concerns doings in Sonoma County by two men: Frank Doyle, president of the Exchange Bank as well as the Santa Rosa Chamber of Commerce, and Press Democrat editor/publisher Ernest Finley. Although Doyle modestly said he was “just one of the hundreds who helped to put the bridge over,” he always will be remembered for kicking the project off by organizing the January 13, 1923 conference in Santa Rosa which brought together over 250 bankers, business leaders and politicians, which earned him his spot standing next to the governor and the mayor of San Francisco when the bridge was officially opened. Finley was the indefatigable champion for the cause, turning the Press Democrat into a soapbox for promoting funding and construction, cheering every nugget of good news and booing every bit of bad.

After Finley’s death in 1942, however, the story shifted; it was said the newspaper suffered by losing subscribers because of its bridge advocacy and Finley was a warrior editor battling powerful railroad, logging and farm special interests opposed to the bridge. This version has taken root over the years in the PD and elsewhere; here’s the version from the Media Museum of Northern California: “…In this particular crusade, which spanned at least two decades, Finley stood almost alone…he was opposed by nearly everyone. His business suffered as he lost advertising accounts and subscriptions. But he continued the campaign, insisting, ‘Damn the circulation! The bridge must be built!’” That’s now his legacy quote although it’s probably apocryphal.1

The problem with that narrative is it’s not really true.

The only special interest actually fighting bridge construction was (surprise!) the ferry companies, which were controlled by Southern Pacific – their astroturf citizen’s groups and 11th-hour courtroom posturings were widely viewed as transparent attempts to delay the inevitable clobbering of their businesses once cars and trucks could drive the bridge. More about that in a minute.

What irked Finley and the other boosters far more was the 1927-1928 pushback from a scattered group of Sonoma County property owners whose anger was whipped up by an anti-tax rabble-rouser.

Ladies and gents, meet Cap Ornbaun, fulltime crank.

Casper A. Ornbaun was always identified in the newspapers as a San Francisco lawyer and he indeed had an office in the landmark Spreckels Building on Market Street, although it seemed he didn’t use it much – on the rare occasions when his name appeared in the papers for doing something attorney-ish it was almost always about handling a routine probate estate, usually in the North Bay. While he lived in Oakland he told audiences he was fighting the bridge as a Sonoma County taxpayer; he owned the 18,000 acre Rockpile Ranch above Dry Creek valley which was used as a sheep ranch. (In a rare non-bridge court filing, he sued a neighboring rancher in 1937 for briefly dognapping four of his sheepdogs, demanding $6,000 for “tiring them and causing them to become footsore and unable to go through the regular shearing season.”)

Why Ornbaun so loathed the idea of a bridge across the Golden Gate is a mystery, but he turned the fight against it into a fulltime cause – maybe it was his midlife crisis, or something. Starting in 1926 it seems he was in the North Bay almost constantly, arranging small group meetings where he could bray and bark against the bridge project.

At least once Mark Lee of the Santa Rosa Chamber of Commerce was invited to formally debate with Ornbaun, but otherwise his speaking engagements were rant-fests attacking anyone or anything connected to the project, including the Press Democrat. At one appearance in Sebastopol he came with dozens of copies of the PD which he handed out to prove the paper was “the bunk.”

The Santa Rosa papers mentioned him as little as possible (no need to give him free publicity) but his appearances in small communities like Cloverdale were newsworthy and the local weeklies often quoted or paraphrased what he had to say. Here are a few samples:

|

Only San Francisco weekenders would ever use the bridge |

|

Strauss is a nobody; Strauss only knows how to build drawbridges; Strauss realizes it will be impossible to actually build it and is just looking to make a name for himself |

|

It will cost over $125 million, or about 5x over estimates |

|

Safeguarding against earthquakes will cost an additional $80-100 million |

|

Maintenance costs would be $5,707,000 a year; it will cost $300,000/year to paint it |

|

It will be impossible to get enough cars across the bridge to have it pay for itself |

|

It would run a deficit of $4,416,230/year |

|

It will take too long to cross it |

|

Nobody knows if people would prefer driving across a bridge rather than crossing the bay by ferry |

|

If it collapsed during construction we would be out our money with nothing to show for it |

|

It would be a high profile target during a war and if it were bombed the Navy fleet would be bottled up in the Bay (that was actually a 1926 Navy objection) |

|

The Board of Directors are not “angels” |

His main accomplice in bridge bashing was James B. Pope, a civil engineer who once worked for the Southern Pacific railroad. Ornbaun praised him as “a consulting engineer of prominence” and “the boy who knows the bridge business” (Pope was 61 years old at the time) because he had once built a 310-foot wagon bridge in San Bernadino county. The wacky cost estimates above likely all came from Pope, who finally decided the bridge would cost exactly $154,697,372 based on his analysis of geodetic survey maps. Strauss had, by the way, offered to share with him the studies prepared by his engineers, but Pope declined to look at them because he “did not need it.”

Ornbaun, Pope and a couple of others had been busy fellows in 1926-1927 and collected about 2,300 signatures of property owners who wanted to opt-out from the proposed Bridge District.2 This meant court hearings in each of the counties with sizable opposition – a process which delayed the bridge project by a full year. But hey, the hearings gave Ornbaun a chance to strut his stuff in courtrooms and cross-examine Strauss, Doyle, Finley, and other project leaders, seemingly fishing for someone to admit the whole plan was a scam or at least that true cost would be closer to Pope’s absurd estimates.

What did come out in testimony was that the booster’s motives were far less altruistic than expressed at the 1923 conference, where it was said the high-minded mission was uniting the Bay Area into “one great thriving populous community,” and bridging the Golden Gate “cannot be measured in dollars and cents.” They were very much using dollars and cents as their measuring stick; Doyle and others who testified were clear their primary objective was jacking up Sonoma and Marin real estate, and they originally wanted Strauss to build something fast and cheap.

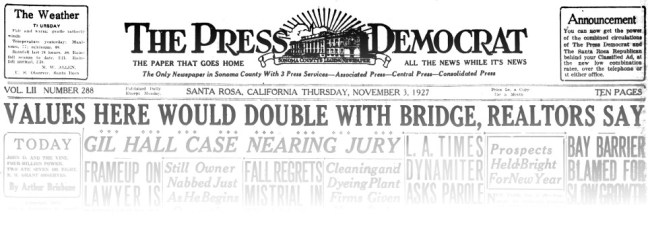

Although the 1927 PD headline below says property values might double, some of the actual testimony on that day predicted it would shoot up to 400 percent. And even if the bridge couldn’t built for some reason, they were already ahead – speculators had been buying and selling Marin and Sonoma land on the promise of the bridge almost immediately after the 1923 conference.

Sorry, Casper – despite all your efforts, the court threw out your case at the end of 1928. That meant the Bridge District could be formed and impose a small property tax to pay for tests and studies to see if the bridge could be built at all. Ornbaun continued to rattle around for a couple of more years making threats to sue, but no one paid much attention.

Sorry, Casper – despite all your efforts, the court threw out your case at the end of 1928. That meant the Bridge District could be formed and impose a small property tax to pay for tests and studies to see if the bridge could be built at all. Ornbaun continued to rattle around for a couple of more years making threats to sue, but no one paid much attention.

Flip the calendar ahead and it’s 1930, time for the District’s six member counties (San Francisco, Marin, Sonoma, Del Norte, parts of Napa and Mendocino) to vote on a $35 million bond measure to pay for construction. And suddenly there are new bridge opponents: The Pacific American Steamship Association and the Shipowners’ Association of the Pacific Coast. They’re saying the bridge might be too low for safe passage, and there should be first an independent investigation by the state – never mind that the War Department had already approved it as having enough clearance for any ship in existence or under construction.

The Press Democrat and ads by the Bridge District fired back that the “Ferry Trust” was using the associations as front groups to confuse voters, but never explained the connection. Perhaps they didn’t know at the time that the two associations were essentially the same company, in the same offices and the president of both was the same man: Captain Walter J. Petersen – a man who apparently had no familiarity with steamships except as a passenger. The “Captain” in his title referred to his Army service in WWI, or maybe because he was also a captain in the Oakland Police Department in the 1920s (he was Police Chief for awhile, and always referred to as “former Chief” in print except when the reference was to the associations).

Sorry, Captain/Chief – the bond passed with overwhelming support, and nothing more would be said about those serious threats to navigation which were keeping you awake nights. To celebrate, Santa Rosa threw a “Victory Jubilee” parade which included a huge bonfire in the middle of Fourth street, with an effigy labeled “Apathy” thrown into the flames.

The last challenge to the bridge happened in 1931-1932, just months before construction was to begin. This time it was a suit in federal court charging the Bridge District was a “pretended corporation” so the bond was null and void. This time the ferry companies convinced two businesses to act as fronts for them.3 This time the ferry companies used their customary law firm to represent their proxies in court. This time it was so transparent that the ferry companies were behind this crap the American Legion and other groups demanded a boycott of the ferries as well as the Southern Pacific railroad. This time the ferry companies gave up in August, 1932, rather than pursuing their nuisance suit all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

What’s truly amazing about all this was the contemptuousness of the ferry companies, no matter what. Sure, our lawyers are representing those companies in the anti-bond lawsuit, but so what? We’re not actually a party to the suit! No, the bridge is not necessary – our ferries are more than capable of handling the traffic demands across the Golden Gate! Never mind that there were routinely hours-long backups on the auto ferries during peak times. At the end of the 1926 Memorial Day weekend there were eight thousand cars in Sausalito queued up for a spot on a ferry. Many gave up and parked their autos as far away as San Rafael so they could get a seat on a ferryboat and make it in to work the next day. It took three days working around the clock just to clear the line of people who were still patiently waiting with their cars.

It was because of these crazy bottlenecks that everyone, everyone, hated the ferries so much that the North Bay was ready to consider a ferry boycott, even though it would have cut us off from nearly all connection to San Francisco – we might have been forced back to the pre-1870 heyday of Petaluma riverboats.

Without its monopoly, the ferry was doomed. Where they had earned a 25 percent profit a year (!!) in the mid-1920s, they lost $1,000,000 in 1937 after the Golden Gate Bridge opened. The company slashed fares. They tried to sell the franchise to the Toll Bridge Authority for $3.75M. Finally in July 1938 – 14 months after the first car drove across the bridge – Southern Pacific closed the ferries to the public.

But during the days of opening celebration, the ferries were never mentioned. On that 1937 Memorial Day weekend the public could not wait to be on their new bridge. During the preview “Pedestrian Day,” 202,000 came to walk the bridge, so many that the turnstiles couldn’t keep up; they opened the barriers and put out tin buckets for people to throw in the nickels. The Press Democrat reported bands played from the San Francisco shore as bombs burst in the clear, deep blue sky.

In Santa Rosa there was a breakfast held in honor of Frank Doyle – who insisted he was the “stepfather” of the bridge, not its father. Mark Lee – the former Chamber of Commerce guy who debated Ornbaun a decade earlier – reminded the audience that the prize was still boosting the town: “…you face great opportunity. The tourists’ dollars, as well as those of business investors and home seekers will find a place in your community, now made so accessible to the thousands who will come into northern California.” Ernest Finley spoke of the “untold advantages and development for Santa Rosa” brought by the bridge.

On the editorial page Finley also reminded that thousands of people would be driving through Santa Rosa enroute to the ceremonies, and the governor of Oregon and other officials were being given a reception in Juilliard Park that afternoon. “Never before has Santa Rosa, destined to be the focal point for population and industry after the mammoth span is opened,” he wrote, encouraging residents to greet the cavalcade by lining Mendocino and Santa Rosa Avenues, showing “a proper display of enthusiasm.” There was much to cheer with enthusiasm that day, particularly if you were a Sonoma County realtor.

| 1 The “Damn the circulation” story first appeared as an afterword to “Santa Rosans I Have Known,” a collection of Finley’s thumbnail descriptions published in 1942 after his death. There Press Democrat Publisher Carl R. Lehman wrote that Circulation Manager McBride Smith approached Finley at his desk and told him the paper was sometimes losing 50-100 subscribers per day. “We can’t keep going at this rate. Our circulation will be ruined if this keeps up.” Lehman continued, “without looking up from his desk, Finley replied in his quiet but determined voice: ‘Damn the circulation. The bridge must be built.'” Smith recounted the story himself in a 1949 PD tribute to Finley but added, “he pounded the desk with his fist” as he said it. While the quote certainly matches Finley’s sentiments, it seems like an odd thing to blurt out to an office employee. |

| 2 The anti-Bridge District count was 823 property owners in Napa and 902 in Mendocino. There were originally 574 signatures from Sonoma County, knocked down to 555 by the time the hearings began in November, 1927. That’s likely close to the number of Press Democrat subscribers who cancelled. |

| 3 The two companies in the 1932 federal suit were the Del Norte Company, Ltd. (identified in the press only as “a large Del Norte property owner” and a “lumber firm”) and the Garland Company, Ltd. real estate firm of San Francisco led by Robert E. Strahorn, one of 92 property owners who had joined a taxpayer’s anti-bridge group as part of the 1930 opposition to the bond. The president of Southern Pacific-Golden Gate Ferries, Ltd. S.P. Eastman admitted in court he had sent a letter to Del Norte Company asking them to file the suit and promising to pay all legal fees (wire service story in Press Democrat and elsewhere, Feb. 20, 1932). Their involvement, combined with a September 3, 1925 editorial in the San Francisco Examiner, “Bridge No Foe to Lumbermen”, has led modern writers to claim there was substantial bridge opposition from logging interests, but I don’t find that mentioned in any of the voluminous coverage of all things related to the bridge in the Press Democrat, Ukiah papers, or elsewhere. |

‘It’s the Bunk,’ Ornbaun Says In Discussing S.F. Bay Span

…Ornbaun was armed with many generalities, few if any figures, and an armful of Press Democrats. He spent most of his time asserting that the Press Democrat was the bunk and seeking to explain how the newspaper had sold itself to the bridge project. Incidentally, he asserted also that the bridge project was “the bunk.”

“The bridge can’t be built. I know it can’t be built. It is impossible to build it. And after it is built it will cost $300,000 a year to paint it. Such, in effect, was his reference to the proposed span from San Francisco to Marin county.

“I am interested in this fight only because I am a Sonoma county taxpayer,” he asserted. He referred to the fact that he represents 20,000 acres of Mendocino and Sonoma county land, but did not mention that it was sheep land.

“I have not been promised money by the railroads or timber interests, he continued. “When the bridge is built it will take too long to cross it.”

The speaker took occasion to flay Joseph B. Strauss of Chicago, one of the country’s foremost bridge engineers, by saying Strauss is “guessing” in his Golden Gate bridge design. He praised one Pope, who in a Humboldt county meeting admitted he was not a bridge engineer, as “the boy who knows the bridge business.”

“I hope to address more people next time I speak,” concluded Ornbaun, speaking to a crowd which had dwindled to about 50, about half of whom were from Healdsburg and points other than Sebastopol…

– Press Democrat, March 17, 1926

BRIDGING THE GOLDEN GATE

THERE IS AN OLD SAYING to the effect that the luxuries of today are the necessities of tomorrow. We also have the necessities of today that must be met without wailing for the tomorrows. With these must now be classed the bridge across the Golden Gate, once regarded merely as an idle dream.

San Francisco, cooped up as she is with a land outlet in only one direction, has come to realize that a bridge across the Golden Gate is necessary to her further growth and development. We of the North Bay counties know only too, well that this section of California can’ never come fully into its own until we have been brought into direct connection with the metropolis.

Engineers agree that the bridge can be built. Financiers assure us that the necessary funds will be forthcoming. Under the circumstances, no time should be lost in putting the project under way. With such a spirit back of the movement as was manifested here Saturday, there seems to be no good reason why actual construction should not begin at a very early date.

Then watch us grow!

– Press Democrat, January 14, 1923

You Can’t Convince Him

Arguments heard from time to time against the feasibility of the Golden Gate bridge project represent for che most part a set mental attitude of those who do not want to be convinced. You cannot discuss projects of this character with men who begin by sweeping aside with one breath all the arguments in its support, and attempt to start from there-There is the man, for instance, who sets his judgment against that of the worlds foremost engineers and says the bridge cannot be built at all. We also have the man who has heard somebody opine that the cost will not be twenty-five millions as has already been carefully computed by experts, but sixty or eighty millions, and who knows it will really cost a lot more. We have also the individual so constituted that upon his mind facts already established and details actually accomplished make no impression. He does not want to take them into consideration and so ignores them or else calmly denies their existence There is also the man who is devoid of imagination. He cannot possibly see how connecting this part of the state with the rest of California and cutting out the troublesome ferries, could improve conditions, add anything to our population or increase property values The bridge cannot be built, because nobody has ever built one like it up to the present time; if possible to construct such a bridge, its cost would be many times that estimated by people engaged in the business, and therefore prohibitive; the cost would not be met by the collection of tolls, as planned by its projectors, but from the pockets of the taxpayers; it is a county matter rather than a district undertaking, as set forth in the law, and consequently if the bridge should be constructed and finally prove unsuccessful final responsibility would rest with the counties making up the district and perhaps with some one county alone, with the result that that county would be wiped off the map; there is no way one can prove that people would cross on a bridge in preference to crossing the bay by ferry, or that more people would travel up this way if they could do so more conveniently than they can at present, because that fact has not yet been demonstrated; if the bridge should be built and something should happen to it later on, or if it should collapse during time of construction, the bonding companies might net pay and we would be out our money and have nothing to show for it these are some of the arguments of the man who is against the project for reasons of his own, but does not care to come out and say so. Talking with him is a waste of time.

– Press Democrat, August 1, 1925

Great Engineering Feat Proposed to Connect Marin-San Francisco Counties by Bridging the Golden Gate

Mr. James H. Wilkins, one of the eldest residents of San Rafael and a man who has the best interests of the county at heart has interested himself in the great scheme of connecting Marin County with San Francisco county by the construction of a massive bridge across the Golden Gate.

Would Extend From Lime Point to Fort Point Bluffs

A lengthy article accompanied by a map was presented in last Saturday’s Bulletin. It is not a new scheme but has been talked of for a great many years. Nothing, however, as definite as the plan therein presented by Mr. Wilkins has been advocated. This great project should appeal not only to the residents of Marin County but the residents of the entire northern part of the State.

Quoting from Mr. Wilkins communication the following plan is outlined:

From Lime Point To Fort Point Bluffs“To give a general descriptive outline, the abutments and backstays would be located, respectively, on the rocky blue of Lime Point and on the high ground above Fort Point. The breadth of the “Gate” here is 3800 feet. The towers over which the cable pass, would be so located as to give a central span of 3000 feet, and side spans of approximately 1000 feet. The catenary, or curved line formed by the suspended cable, would have a central dip of approximately 65 feet. Therefore, the elevation of the towers must be 215 feet to secure the clearance required.

“From the southern abutment the railroad line would descend by a threequarters of 1 per cent grade, bringing it precisely to the elevation of the intersection of Chestnut and Divisadero streets, a block away from the site of the Tower of Jewels, that marked the main entrance to the never-to-be-forgotten Exposition. Just a few blocks farther is the belt railroad that traverses the entire waterfront, the business heart of the city, ready to be a link of the great commercial carrier of the western world.

Pedestrian Promenade Across Strait

Novel IdeaFrom this plan might be omitted the upper or promenade deck, with material reduction of cost, leaving only rail and automobile roadways. The promenade is, indeed, more or less of a matter of sentiment. Crossing the Golden Gate in midair would present, perhaps, the most impressive, emotional prospect in the world. Why should not those enjoy it who are, by unkindly circumstance, still constrain travel on their own legs? Moreover, it would be best observed leisurely, not from a flying train or automobile.

“After the shock of the bare statement, the first and preliminary inquiry arises, Is the project practicable—and practical?

“Beyond cavil or question, yes—far more so than the proposed five and a half mile bridge between Oakland and San Francisco. This is not a guess. I do most things in life indifferently, I am a graduate civil engineer, know a thing or two about applied mathematics and am familiar with construction work from building pigsties to building railroads—I have built both. The proposed suspension bridge—the central span—would be longer than any other structure of its kind in the world. But that only means stronger material, extra factors of safety. And nowhere in the world has nature presented such an admirable site. Bluff shore lines and easy gradients on either side —no costly approaches and still more costly right of way.

Idea Was Old As as State’s Railroading

The idea is almost as old as railroading in our State. When the Central Pacific made its entry into California, the original route via Stockton, Livermore Pass, Niles canyon, with its long detour and heavy grades was found to be impracticable. The company, therefore surveyed a more direct low-level line, departing from the present route east of the Suisan marshes, passing through the counties of Solano, Napa, Sonoma and Marin. In 1862 I was present at a session of the Marin Supervisors when Charles Crocker explained his plans, among which was a suspension bridge across the Golden Gate. Detail plans and estimates for such a bridge were actually made by Central Pacific engineers. But, along came a man with a newer idea—the transfer of trains across Carquinez straits by steamer and the extension of the Oakland mole to tide water. And so the suspension bridge project died.

“The length of the proposed bridge from Oakland to San Francisco is approximately 27,000 feet, as against approximately 5000 feet from abutment to abutment of the suspension bridge. The former, if constructed on arches, could not fail to interfere seriously with navigation of the upper bay. One serious objection seems to be that the projectors do not know where to land it on our side of the bay. One engineer gives it a terminal on the summit of Telegraph Hill!

Cost Ranging From 25 to 75 Millions

“The estimates of the cost of the San Francisco-Oakland bridge range from 25 to 75 million dollars.

From such data as I have, and by comparison with the cost of similar structures, a suspension bridge across the Golden Gate could be built for less than ten million dollars. This is an extreme estimate, accepted by several engineers to whom this article was referred.

“But as a final and fatal stumbling block, the foolish jealousy between the rival towns will never permit them to join in a great constructive enterprise till human nature has materially changed. That will not be in my time or yours.

“Of course, it will be objected to at once that both terminals of the suspension bridge would necessarily be located on military reserves of the government. But such an objection could hardly stand. Indeed, it ought to be an immense strategic advantage to have the two great defensive points of the harbor connected up. Doubtless the government would gladly grant the easement. It is in inconceivable that any government would arbitrarily block one of the greatest and most significant undertakings ever attempted by civilized men. Certainly no hostile attitude was assumed at Washington when the plan was materially considered over forty years ago.

Financing of Project a Community Investment

“Still as the intimate concern of San Francisco and the North Coast counties, the undertaking should be properly financed by these communities, as a public utility concern. Having only a sincere desire to be closely united, this ought to be simplicity itself, for the extremely simple reason that a bond issue of $10,000,000 would take care of itself and speedily retire itself. The Northwestern Pacific Railroad alone spends half a million dollars a year to maintain a line of steamboats between San Francisco and Marin county points, which is extremely wicked interest on the total cost. Very small charges for its use would soon pay interest, principal and all.

And if, from a financial standpoint, it were a total loss, still San Francisco would be far ahead. The city could well afford to pay $10,000,000 or more for the greatest advertisement in the world—for a work never before surpassed by the imagination and handiwork of man. Whether viewed from its lofty deck, commanding the contrasting prospect—to the west, the grand old tumultuous ocean; to the east, the placid bay; or from incoming ships; or from the landward hills: it would bid fair to remain forever the most stupendous, awe-inspiring monument of our modern civilization. And it could have no rival, for there is only one Golden Gate in the world.

Greatest Of World’s Harbor Improvements

“Even in remote times, long preceding the Christian era, the ancients understood the value of dignifying their harbors with impressive works. The Colossus of Rhodes and the Pharos of Alexandria were counted among the seven wonders of the world. The same tendency appears in our own times, witness the cyclopean Statue of Liberty at the entrance of New York harbor. But the bridge across the Golden Gate would dwarf and overshadow all.”

This proposition has created more enthusiasm in San Rafael than any other for some time. Mayor Herzog and the City Council have all endorsed it enthusiastically. The Central Marin Chamber of Commerce is expected to act at their next meeting and the County Supervisors will also probably act at their meeting next week. While the cost of such a bridge would be enormous it is not insurmountable as pointed out in Mr. Wilkins’ article. Such a proposition if constructed would undoubtedly double the value of real estate in Marin county in a short time and no doubt in a few years the population of Marin county would increase five-fold. This proposition is not a wild-cat dream and deserves a lot of consideration.

– Marin County Tocsin, September 2 1916