The high school auditorium was packed that Sunday morning in 1937 with people from all over Sonoma county. Uniformed boy scouts ushered the last of the audience to their seats as an announcer hushed the audience. Promptly at 10:30, the speakers crackled to life with a recording of the Star-Spangled Banner.

Waiting at the microphone for the music to finish was a slight 67 year-old man in his customary three-piece suit. “Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. With the playing of the national anthem, station KSRO, voice of the Redwood Empire, takes the air for the first time.” He continued with the required sign on announcement before ending: “This is Ernest Finley speaking and I now turn this fine new radio station over to the people of the Redwood Empire for their use and enjoyment.”

Finley wasn’t really handing over KSRO to the public, of course – he was the sole owner of the station as well as the two newspapers in town, the Santa Rosa Republican and the Press Democrat, where he was also editor and publisher. The papers would promote the station which would promote the papers. So cozy was this little media empire that the broadcasting studios were in the PD building on Mendocino Ave.

After an invocation by the rector of the Church of the Incarnation and playing a recording of religious music, the live program continued with 15-minute salutes to Marin county and seven communities in Sonoma. Usually the mayor said a few words which were followed by music from someone in that town – there had been talent contests over the previous weeks to choose the artists. Santa Rosa was represented by a singer and Walter Trembley, harmonica virtuoso; Cloverdale sent Glen Bonham, imitator.

There were other live performances that day woven between recorded music before the big dedicatory program at 3:00, where the mayor of San Francisco spoke and the KSRO orchestra performed, along with others. The hour long program closed with an audience singalong.

And that was pretty much the end of the first broadcast day, September 19, 1937. The station signed off at 6PM, having only a permit to operate from dawn to dusk. This was typical of little commercial stations all over the country; night hours were only for the high power clear channel stations that could sometimes be heard for a thousand miles. With its 250 watt (!) transmitter, KSRO reached from San Rafael to Ukiah – but came in as far away as Eureka and San Jose when conditions were ideal.

By 1937 the radio market was well-established in the Bay Area. Probably any radio in Sonoma County could pick up the big stations in San Francisco such as KGO, KSFO and KPO (which became KNBR), which were network affiliates broadcasting all the popular programs we associate with the golden age of radio. During the day there were the soaps, including Vic and Sade, Our Gal Sunday and Ma Perkins; in the evening were the top shows such as Burns and Allen, One Man’s Family, Amos ‘n’ Andy, Gangbusters, Jack Benny.

(RIGHT: KSRO schedule for September 24, 1937; local programming highlighted)

(RIGHT: KSRO schedule for September 24, 1937; local programming highlighted)

Pipsqueak independent stations like KSRO instead relied on a mix of local programming and a transcription service (the one first used by KSRO was NBC’s Thesaurus, upgraded soon to World). A subscribing station would get 16-inch records that played at 331⁄3RPM, which would provide fifteen minutes of content per side. Thus a station operating on the cheap could fill much (even all!) of its schedule using just an engineer and an announcer – who could also be the engineer – to read commercials and announce time/call letters. And as you see by this schedule taken from its first week of broadcasting, that’s pretty much what KSRO did at the beginning.

The problem with transcription services was that their offerings often… sucked. In its earliest weeks KSRO mostly played transcriptions of D-list musicians such as the Mountaineers hillbilly band (who apparently never made a record) and Robin Hood Bowers (somewhat known for a 1919 ditty, “The Moon Shines on the Moonshine”). The station also broadcast generic canned programs with titles like “Melody Time” and “Rhythm Makers.” It was music to do chores by.

Those transcription shows were mostly sustained (unsponsored, except promos for other shows or perhaps Finley’s newspapers) because KSRO didn’t have many advertisers at its outset. The first sponsor was mentioned only a few days before the premiere broadcast – the White House Department Store would advertise on the noon newscast.

Among other early live studio programs were 15 minute weekly shows by The Rincon Valley Ramblers, a quartet which entertained sometimes at lodge or club meetings, and “Songs of the Island,” with Hawaiian melodies sung by the Carroll Boys from Napa: Slip, Arky, Gat and Alky. There was the 30-minute “Mickey Mouse Club” on Fridays at 4, which resurrected the riotous live show that once commandeered the California Theater on Saturday afternoons (see “LET’S ALL YELL AT THE MICKEY MOUSE MATINEE“).

On weekdays the anchoring live show was the mid-afternoon “Time for Tea,” which was completely free form. There were usually announcements from women’s clubs, churches and the like, but you might also hear some kid scraping his bow across a violin string or squeezing an accordion. They sometimes did a “Name That Tune” type game show or brought in an elementary school class to do a spelling bee.

The popular morning “Breakfast Club” opened the broadcast day at 7 (sadistically, by beating a gong that nearly blew out your speaker) and received lots of mail because the host encouraged listeners to send in their birthdates to be announced on air. A farmer from the Sonoma Valley who wanted to sell his ranch wrote that he would come on the show and do his (presumably terrific) imitation of a calf and a squeaky clothesline in trade for commercials.

Gradually over the first couple of months their live programming pushed out more of the transcribed shows. KSRO was becoming a radio station that locals wanted to actively listen to instead of just being a source of ignorable background music.

Remotes were a large reason for the station’s success. They kept their portable transmitter busy; Evelyn Billing’s organ concerts on the grand instrument at the California Theater were always popular, although sometimes she played at the Chapel of the Chimes, which wasn’t exactly a venue where one expected to hear peppy dance tunes.

They broadcast SRHS and Petaluma High football games live from the 50 yard line; Sunday morning church services; KSRO was there for the opening of Rosenberg’s Department Store (now Barnes & Noble). They took the equipment to Healdsburg to cover their Veterans Day celebration: “If the weather is nice you will get a word by word picture of the parade, bands and all. If it rains you will probably get a drop by drop sound of a rainstorm in the Redwood Empire.”

Most of all, they broadcast live every weekday at 12:45 from the Exchange Bank corner downtown. The “Man on the Street” show was easily KSRO’s most popular program of 1937. The very first question asked: “Do you think Santa Rosa should have stop lights at downtown intersections?”

KSRO wasn’t the first radio station in Santa Rosa, however. Years before – as the radio era was just beginning – there was KFNV, broadcasting with a mighty five watts from March 1924 to October 1925, off on Sundays.

Lennard Drake – yes, that’s the spelling – and his wife Aimee, who ran the Drake Battery and Radio Shop downtown, convinced the publisher of the Republican (not yet owned by Finley) to provide space for an equipment room at the newspaper’s office on Fifth street. They put it together with the aid of local radio entusiasts and using gear unapproved by the government.

Programming at KFNV was mainly phonograph records, a player piano and anyone who drifted in to talk. Their only regularly scheduled program was the “Sunset Matinee,” a 6:30PM children’s program of bedtime stories by “dear oid Uncle Silas.” The Republican radio columnist noted Silas was the father of two and “I know for I have had the pleasure of seeing them” – which is such an odd thing to write that it makes one wonder if there were whispers about the doings over at La Casa Silas.

In 1937 Lennard was interviewed by the PD and said the station folded because of lack of sponsorship. “Radio was [considered] just a child’s toy, a fancy of the moment.” Aimee added, “no one, of course, in those days foresaw commercial sponsors.” Apparently the only advertisers were the Drake radio store and the Republican. (By 1937 the Drakes had dropped the radio business and were now selling electrical supplies, including fixtures and wiring for KSRO.)

In 1937 Lennard was interviewed by the PD and said the station folded because of lack of sponsorship. “Radio was [considered] just a child’s toy, a fancy of the moment.” Aimee added, “no one, of course, in those days foresaw commercial sponsors.” Apparently the only advertisers were the Drake radio store and the Republican. (By 1937 the Drakes had dropped the radio business and were now selling electrical supplies, including fixtures and wiring for KSRO.)

A dozen years passed between the end of KFNV and birth of KSRO and in that time radio had become an essential part of daily life. By 1937 there were 28,000 households from San Rafael to Ukiah where the radio was on 3-4 hours during the day – all listening to commercials for stores in San Francisco, Oakland or Sacramento.

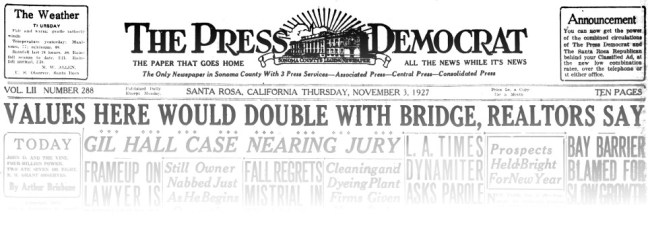

Not having a local station was also a big reminder that the North Bay wasn’t a full-fledged member of the Bay Area. Promoters and developers in Marin and Sonoma counties had pushed through construction of the Golden Gate Bridge primarily to draw tourists and increase property values; when it opened just a few months before KSRO went on the air, Finley spoke of the “untold advantages and development for Santa Rosa” the bridge would bring.

Likewise KSRO wouldn’t be intended only for locals seeking department store sales on tea towels. For those tuning in from the fringes of its reception area, it also would serve as an advertisement for Sonoma county itself – that this was a great place if you were thinking of buying a little chicken farm or looking to escape the city. The homey vibe of shows like “Time for Tea” were a panacea to the slick productions cranked out by the networks and big urban stations.

But Finley et. al. weren’t alone in viewing the region as an untapped market; when the Press Democrat Publishing Company filed for a broadcasting permit from the Federal Communications Commission in early 1935, there was already someone ahead of them in line.

Two men from Berkeley, Arthur Westland and Jules Cohn, had applied for a 100 watt station to cover Santa Rosa alone. They were pioneers in the radio biz and operated KRE in Berkeley, a station which dated back to 1922.

In February of 1935 the Santa Rosa Chamber of Commerce – always in lockstep with Finley and the PD – sent the FCC a telegram asking them to deny the Berkeley application because Westland had falsely told the Commission “there was no opposition to the proposal.” Two months later an FCC examiner recommended denying Westland and Cohn. The reasons, according to the PD, were that it was “not shown there was a substantial need for additional broadcast service in that area” and that any station was unlikely to be a viable business because there just wasn’t enough interest.

Yet that same April there was a formal hearing on Finley’s application. Presumably he and others attended that meeting in Washington, but it wasn’t mentioned in either newspaper at the time. Final arguments for the permit were made in October 1936, and a month later the FCC denied the Berkeley-ites and granted the license to Finley.

Both of Finley’s newspapers covered the 1937 build-out of KSRO obsessively. Readers saw photos of the antenna going up in the Laguna – it was at the corner of modern-day Finley and Leddy avenues – and the transmission “shack” built at its base (it remained there even after the antenna was moved close to Stony Point Road, but burned up in a 1968 fire caused by homeless squatters).

Both of Finley’s newspapers covered the 1937 build-out of KSRO obsessively. Readers saw photos of the antenna going up in the Laguna – it was at the corner of modern-day Finley and Leddy avenues – and the transmission “shack” built at its base (it remained there even after the antenna was moved close to Stony Point Road, but burned up in a 1968 fire caused by homeless squatters).

The papers also admiringly described the remodeling done to turn the second floor of the Press Democrat office into broadcast studios (alas, no photos). Since the rooms had to be soundproof there were no windows; there was a gee-whiz astonishment that they were to be air conditioned full time.

They hoped to be running by August 15 so they could broadcast remote from the county fair, but obstacles arose which were not explained. But a month later there was that ceremony where 750 people packed into the high school auditorium.

KSRO was now on the air.

The station may have continued down its uneventful path for years, slowly building an audience as it kept improving local programming. But before it was even three months old its coming of age moment arrived: People’s lives became dependent upon listening to KSRO.

In December 10-11, all of Northern California was saturated by ultra-massive rains. The PD called it “worst storm in all history” and “the greatest havoc ever wreaked in Sonoma County.” Unfortunately, we can’t compare it to other disasters because Russian River flood records are inexact before 1940 – but old-timers insisted it was the worst in 60-70 years. It was the damage caused by this flood that would eventually lead to the construction of the Warm Springs Dam.

Parts of Healdsburg were under ten feet of water and the deck of its railroad (Memorial) bridge was covered. Goats and calves were herded into a church near the town – and then had to be moved again a couple of hours later when the water reached the church. A two story house from Rio Nido was hurled against the Guerneville Bridge. Before the water reached the switchboard, operators at the Monte Rio telephone exchange were wearing hip boots and standing in 40 inches of water.

The Russian River kept rising, first three inches an hour, then four. Five. Electricity was out everywhere and phone service was spotty. Hundreds of families, hungry and cold, were huddled in upstairs bedrooms, in attics, on their roof and nobody knew how bad it would get or what to do – unless you had a battery-powered radio tuned to KSRO.

News bulletins from the station warned listeners to conserve drinking water because well pumps wouldn’t be working for days. There were phone interviews with mayors or other officials in many of the hard-hit towns, updating citizens on the latest conditions. There were road reports from AAA. In Geyserville, the director of relief work announced on KSRO that anyone needing help should fly a white flag from the top of their house. Soon a dozen or more flags were spotted by volunteers with binoculars watching from high ground and they directed rescue boats where to go.

Amazingly, no one died locally during the disaster – and KSRO surely must deserve some measure of credit for that.

Amazingly, no one died locally during the disaster – and KSRO surely must deserve some measure of credit for that.

(RIGHT: KSRO schedule for August 6, 1938; local programming highlighted. Capitalized shows were sponsored)

In the months that followed the local radio columnists mentioned the growing amount of fan mail being received by “KSRO personalities.” Live programming was now about half the schedule. Added to the schedule were popular new shows such as “KSROlling Along,” the “Italian Program With Guiseppe Comelli,” and the “X-Bar-B Cowhands.” The country-western band was a bit of a coup for the station as they already had a following, having been heard on a San Francisco station for six years before the group moved to the Russian River area.

Finally KSRO gained permission for evening broadcasts and as of August 1, 1938 it was now on the air up to 11 o’clock, midnight on weekends. As before, there was a dedication ceremony (this one featuring 21 year-old Miss Ruth Finley, “concert pianist”) and a short speech by Ernest Finley. He said, in part:

| In inaugurating Station KSRO, we were pleased to call it the ‘Voice of the Redwood Empire.’ We feel that it has been just that. Every effort has been made to bring the various communities of the Redwood Empire closer together. Our survey shows that Station KSRO has a listening audience of 150,000 persons. This does not take into account Oakland, Berkeley, Richmond, San Francisco or any of the cities about the bay, in many of which reception is fully as good as it is here. |

In some ways that moment was as significant as the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge for Sonoma county. KSRO had brought all of us closer together via its news coverage during the flood. And although Finley was thinking of the promotional value of the station luring Bay Area residents, it also meant we could take part of our community with us when we went away.

As your car crossed the beautiful bridge and the northern counties slipped from sight behind the city hills, the signal might become crackly and drift in and out – but it would always be a steady beacon which would later guide you home.