Our country is so divided some are starting to worry it could lead to a civil war. Even Sonoma County is split with neither political party clearly having an upper hand, Democrats mostly in control of the government while Republicans dominate the media. It’s easy to find reasons to sneer at the guys on the other side of the fence; Democrats are in disarray while Republicans bark out conspiracy theories. Both parties have resorted to name-calling and view themselves as unfairly treated victims. And it will probably get even worse – who knows what craziness awaits us next year in 1858?

While Santa Rosa was the county seat it was still little more than a village in the late 1850s. There were about 400 people in the town proper, although there were three times that number living in simple cabins and roughly made houses in the surrounding township. There were six blacksmith shops but only two restaurants; three carpenter shops and one clothing store. A farmer’s town. By contrast, Petaluma was a regional mercantile center – it took at least 90 minutes to reach it by buggy, but it was said half of Santa Rosa still shopped down there.

This is a (long overdue) companion piece to an article I wrote several years ago, “PETALUMA VS SANTA ROSA: ROUND ONE.” That covered the simmering rivalry between the towns, including Petaluma’s insistence it deserved the county seat more than Santa Rosa. There’s some necessary crosstalk between these two items, but the focus here is on the feud between the town’s newspapers. This is not just because of the entertainment value of a good ol’ Victorian-era insult throwdown (ranging from childish taunting about “a set of block heads and dolts” to an almost poetic, “wou’t [sic] somebody hold this high mettled charger? He has already bucked sufficient”). More importantly, the 1850s squabble in newsprint revealed details about Santa Rosa during that era that wouldn’t have been otherwise known.

For example: The early years of the Sonoma Democrat – Santa Rosa’s newspaper – are most associated with its pro-Confederacy position during the Civil War and expressing its raw hatred for Lincoln even before then. But that was when the Democrat was owned and edited by Thomas L. Thompson starting in 1860; the paper had two earlier owners. Were they likewise pro-slavery zealots? Historians mention them only in passing (if at all) so the answers will be surprising.

| – | – |

|

Alpheus Russell and his family made their way here in 1857 from Grass Valley, the year after he made a respectable gold strike worth over $2,000 (more than $80k today). Why they settled at Santa Rosa is unknown – there were no apparent family or social connections in the area.

In his October 22, 1857 debut issue, Russell offered a fine, high-minded mission statement (transcribed below). He vowed the Sonoma Democrat would honestly inform and engage the community; never would the paper “…give utterance to a word that will put to blush the most modest cheek, or invade the pure precincts of the family hearthstone with aught that can grate harshly upon the nerves of the most fastidious.” (Lordy, that’s so perfumed I swear I caught the sickly scent of evening primrose.)

Russell pledged the Democrat would tirelessly fight against those who might seek to split the nation apart “…without resort to the usual too frequent use of disgusting epithets, or low abuse.”

He closed with a promise to expose political hokum and corruption, meanwhile keeping “…free from taint or suspicion the good name of the Democratic party throughout the Union.”

A different piece in that first issue made it clear Russell didn’t see his paper as being in competition with Petaluma’s newspaper, the Sonoma County Journal. “…We have commenced the publication of this paper, not in opposition to our neighbor [editor H. L.] Weston, of the Journal,” he wrote. “[We] shall continue to wish a long continuation of success and prosperity to Petaluma, and the Sonoma County Journal.”

The next Sonoma County Journal responded with its own felicitations, welcoming the launch of Santa Rosa’s “hebdomadal” paper (that’s a twenty-dollar synonym for “weekly”), while complimenting its nice printing and Russell’s writing. “We cordially extend the hand of fellowship.”

All that warm and fuzzy bonhomie lasted exactly two months.

A squabble began when the Journal accused the county and Sheriff Green of not following the letter of the law regarding publication of the delinquent tax list. It was supposed to be printed “on or before the fourth Monday in November” (which was the 23rd that year), giving the public a month’s notice before the property would be sold at auction. But the Democrat published on Thursday, and the tax list was long – the first installment appearing in the Nov. 26 edition and the last on Dec. 10. In the Journal’s view, this meant none of the property could be legally auctioned off.

Before continuing, let’s acknowledge the Journal was technically correct – in no way was printing a partial list on Nov. 26 in compliance with publication “on or before” Nov. 23. But the Journal also deceptively quoted only part of the law. Spreading the list over several issues was specifically allowed, as long as the first installment appeared at least three weeks before the auction. The Democrat had met that criteria, so there was really nothing to the Journal’s alarm bell of something being seriously amiss.

And let’s also recognize the true underlying complaint was that the Journal was upset because the lucrative deal for printing the list was given to the upstart Democrat and not to them. And maybe it should have been; as the oldest county newspaper with the larger circulation, any legal notice in the Journal would be seen by the most people.

Russell slapped back, hard. The Journal’s editorial “manifests more spleen, chagrin, envy and malignity, than is usually found embodied in so small a space, accompanied by so little ingenuity and tact,” he wrote in the next issue. (There are so many mentions of “spleens” in the transcripts below I expect to get Google hits from people looking for medical information.)

His counterattack goes on for over 1,800 words which you can read below, if you must, where he accuses the Journal of “attempts at prostituting the law to unholy purposes” and calls the editor a pettifogger, wiseacre and a lunatic. It ends thus:

| Here we are at once directed to the festering sore from which the Journal is suffering so intensely. It has enjoyed the exclusive patronage of the county officials all its life until quite recently, from which it has grown fat, and now seems to regard its place at the crib as a matter of right, and anything given in another quarter as something wrongfully taken from him. Thus, the Sheriff, the Clerk, the Board of Supervisors, and the Democrat, each in its turn, would suffer from the castigation of the Journal… |

The next day the Journal published a letter from J. J. Pennypacker, who was apparently in charge of the Petaluma paper at the time. Pennypacker accused the sheriff of being in league with a “Santa Rosa clique” or “junto” (political faction). Two months later, a letter signed anonymously “U. Bet” (Pennypacker, of course) went further, claiming the Board of Supervisors approved payment of Russell’s $920 printing bill “rather than incur the displeasure of the clique.” It condemned the supposed faction:

| …a clique of political demagogues at Santa Rosa, who, to subserve their own ambitious, mercenary, and corrupt purposes, had bribed the press of that town…a clique, as venal, as corrupt, and as mercenary as you described them to be, but much more influential, does exist; and that same clique controls the columns, and is endeavoring to support, out of the County Treasury, a paper wholly devoted to their own individual aggrandizement. |

Pretty strong accusations, there. Who were these powerful card-carrying cliquers that secretly ran the county? Pennypacker never got around to naming any of the conspirators, but he just knew they were the puppet masters who had the Board of Supervisors and Sheriff do their bidding lest they might “incur the displeasure of the clique.”

It’s tempting to imagine the clique being the enforcement arm of the Settler party – except there was no “Settler party,” only a disorganized alliance of squatters who wanted to (somehow) invalidate the Mexican land grants. Here they sometimes voted en bloc per 1853, 1855 and the anti-Lincoln vote of 1860 (see “A FAR AWAY OUTPOST OF DIXIE“) but there were many letters from squatters printed in the Journal during those years bemoaning their lack of clout.

Whether or not a real clique/junto existed to any degree is intriguing, but I don’t think the tax list printing is proof of much except perhaps the Sheriff showing political gratitude – Santa Rosa voted heavily for him, but he came in third at Petaluma. Youse dance with them that brung you.

Add to that the Sonoma Democrat certainly needed the business. The newspaper was struggling during its early years, with about half its ads coming from Petaluma at the start; the editor later penned bitter editorials about his thin paper not getting enough local support. By printing the delinquent tax list Russell received a windfall of about $1,000.

For months the tax list feud raged on. In old newspapers, page two was always dedicated to editorials or letters. There, Santa Rosa/Petaluma fans of calumny and defamation were usually richly rewarded; all that’s transcribed below are merely wood chips from a large, rotten stump.

Pennypacker and alteregos “U. Bet” and “Inquirer” doubled down on their campaign against the “Santa Rosa clique,” which he fumed was behind “illegally printing an illegally got up delinquent tax list.”

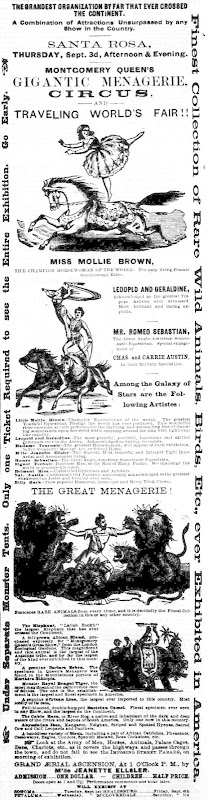

He didn’t seem to have much of a sense of humor but had a great talent for nasty snark (oh, but would he have loved Twitter). When Russell ignored his demands to confess being part of a junto, Pennypacker wrote, “…clear your throat, and speak out like a little man. If you can’t see over nor around this pompous sheriff, stoop a little and peep between his legs, and tell the people why you are so anxious to make an illegal sale.” Pennypacker also got into a snit over the Democrat’s advertisers, at least twice demanding the Santa Rosa paper stop running the “obscene and demoralizing” ad shown here.

(RIGHT: 1858 Sonoma Democrat ad for the Czapkay Grand Medical and Surgical Institute in San Francisco. Dr. Czapkay promised he could cure a vast number of medical complaints, particularly “all forms of private diseases, such as Syphilis, Gonorhoea, Nocturnal Emissions, and all the consequences of self-abuse.”)

(RIGHT: 1858 Sonoma Democrat ad for the Czapkay Grand Medical and Surgical Institute in San Francisco. Dr. Czapkay promised he could cure a vast number of medical complaints, particularly “all forms of private diseases, such as Syphilis, Gonorhoea, Nocturnal Emissions, and all the consequences of self-abuse.”)

Russell lacked Pennypacker’s mastery of the artful sneer – although he made a pretty juicy counterattack after Pennypacker bragged about having time to investigate the hidden hand of the clique because he was “a man of leisure.” In essence, Russell’s comeback was, “I’ll see your stupid outcry over a trivial printing delay and raise your bet with suspicions that a Petaluma junto committed grand larceny.”

As Gentle Reader most certainly recalls, in early 1857 the county treasurer was convicted of stealing the county treasury and state school money. “It is well known,” Russell hinted darkly, the treasurer did not act alone: “…it has been a matter of wonder how certain men not more than sixteen miles from Santa Rosa, having no lucrative business, could become ‘men of leisure’ and always have plenty of money…’U. Bet,’ knows as well as any body else who shared in the spoils of that robbery, and who ‘got the lion’s share.’”

While Pennypacker was trying to incite public fury in early 1858, Russell took on a partner: Edwin Budd, who likewise hailed from Nevada County, California, so the men were surely well acquainted before Budd arrived. I found nothing certain about Russell’s past except for that gold strike, but Budd’s timeline was easy to trace. He had been a printer and newspaperman most/all of his life and was once half owner of the Nevada Journal, the main paper in that county. But when he came here it was during a difficult time; he couldn’t pay a debt of $164.85, so his property in the little town of Rough and Ready was sold at a sheriff’s auction.

Budd quietly took the editor’s chair at the Sonoma Democrat, which seemed to escape Pennypacker’s notice, as he kept gnawing like a pitbull on Russell’s leg.

It’s unclear what role Journal publisher Henry Weston had in the feud. In the longer screeds Pennypacker’s writing style can be spotted, but some could have been written by either of them. But after the Journal’s conspiracy-think of cliques and juntos commenced its third month, Russell/Budd had just about enough and went after Weston, calling him a “pusillanimous little puppy” and a “certain detestably filthy little animal” that’s “proud of his filthiness.”

Their pushback escalated the feud into code red territory. In its next edition, the Journal published a Believe-it-or-Not! style revelation: Russell was a closet Republican.

| – | – |

AN UNSETTLED COUNTRY It’s difficult to grasp the chaos that gripped American politics during the mid 1850s. Newspapers like the Sonoma County Journal navigated those choppy waters by declaring themselves “independent,” which was mostly a way of saying “not Democrat.” The old Whig Party collapsed after the elections of 1856; the American Party, created by the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing movement, looked strong in the middle of that decade but likewise sputtered out shortly after that election. The Democratic party was coming apart at the seams over slavery, starting its divide into multiple northern and southern factions. The newly formed Republican party became the new home for many Whigs, but Republicans had different interest groups as well – some looked down on supporters of abolition as “Black Republicans.” In 1856 Sonoma County the Republican party was small; only seven delegates attended the first state convention, less than half as many than were at the Democrat’s state meeting. Republicans were particularly unpopular in Santa Rosa that year; their presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, received under three percent of the vote – the lowest of any community in the area – and all of the other Republicans on the ballot had similar dismal returns from Santa Rosa. |

It was true. Russell had been a Nevada County delegate to the state’s Republican convention in 1856, while also running as a Republican for Nevada County Supervisor and Public Administrator. Budd was the Republican candidate for Nevada County Justice of the Peace in 1857, merely a few weeks before he began working at the Sonoma Democrat.

As told in the sidebar, being outed as a Republican was toxic in most of Sonoma County, particularly so in Santa Rosa. Weston and Pennypacker kept hammering on the topic over the following weeks, even sending clips to their fellow “independent” newspaper in Grass Valley and getting in return an item that found it amusing for a Republican to be operating a Democratic paper. Of course, the Journal reprinted that in their own pages.

Russell/Budd finally responded with an unsigned, rambling essay titled, “Our Politics.” It’s unclear if it was a personal declaration by one of them or encompassed both (which I think was the intent). In sum: “we were born a Whig” and remained so until the party crumbled; “we steadfastly refused to be called a Know Nothing” but “we have voted for Republicans, and Know Nothings, as well as Democrats.” Freedom for the slaves was out of the question because it would “turn the hordes of Africans in the United States loose.” Several times the piece spoke approvingly of then-President James Buchanan, a Democrat (who, it must be always noted, consistently ranks near the very bottom of lists for worst president in history).

While the Journal’s new round of partisan attacks continued gathering steam, Russell was physically attacked by a Santa Rosa lawyer named James B. Boggs.

Russell’s account of the incident is…confusing. It reads like the sort of overwrought tale you might hear from a middle school kid; Boggs told a friend that Russell had told somebody else a mean lie meant to embarrass Boggs, then Boggs’ friend asked Russell why he did that and Russell said he didn’t know anything about it. (Don’t try to make sense of it – middle school, seriously.)

The key part of Russell’s version is a passing remark about encountering a drunken Boggs on the street: “I crossed the street, shook hands with him, whereupon he showed me a No. of the Petaluma Journal, and asked me to read an article, published in that paper in relation to myself. I told him I had read it, and declined to again.” The next day Russell was in a store when Boggs came up to him from behind and struck him with a buggywhip.

Boggs was fined $50 (“which, it is understood, was paid by one of his friends”) yet subsequently boasted about the assault. “It then became understood that Boggs, partly to gratify his own spleen, and partly instigated by others, had intended it for a personal indignity, that it should be said he had publicly castigated A. W. Russell.”

Some of the gossipy parts of the story are probably true – he does, after all, name the other two men involved – but I have no doubt the real cause for Boggs’ fury was the nasty, inflammatory hit pieces churned out by Pennypacker and maybe Weston. (Russell should count himself lucky; three years later, Boggs was convicted of manslaughter for killing a stablehand in Healdsburg. He was drunk then, too).

The Journal was predictably snide about Russell’s whipping, suggesting he deserved “a little more of the same sort.” But his bruised back and bruised ego were the least of his problems that spring. As the year 1858 progressed Russell and Budd often griped subscribers weren’t paying up: “Up to this time more than one-half of our subscribers have paid us nothing” and, “we would again say to you, friends, that the little sums you owe us, are important to us” and, “there are now about 150 subscribers to the Democrat, mostly living in this county, who have received the Democrat one year, and for which we have never received one cent.”

Further, there were a diminishing number of recurring advertisements from the Petaluma merchants, which had been their mainstay. Now their ad space was mostly filled with short-run local property and livestock sales, legal notices, plus even more snake oil from San Francisco quacks such as Dr. Czapkay and Dr. J. C. Young, who was pushing a “contraceptive” powder (“we would again caution pregnant women from using this preparation, as it would be certain to produce abortion.”)

Between their money woes and continual sniping from the Journal, it’s safe to guess a miasma of worry and gloom hung over the Sonoma Democrat’s office and strained the relationship between Russell and Budd. In June, Budd sold his share of the business to Russell. In August, Russell sold the whole newspaper and related print shop back to Budd. You have to wonder what was going on between the two.

Russell stayed in town for at least a year and a half, operating a grocery and dry goods store on the corner of Third Street and Exchange Ave. Budd immediately took on a new partner, who only lasted a few weeks. His next partner stayed around over a year.

There was another big stink over the Democrat publishing the 1858 delinquent tax list which I will not bore Gentle Reader by visiting, except to say there was no feud with the Journal for this round. Pennypacker was no longer writing editorials there, as he was trying to launch his own newspaper aimed at settlers, following that by starting the Petaluma Argus. (Alas, we don’t know what he had to say on the matter since relevant issues for those publications do not survive.)

Budd clung tightly to his allegiance to the Democratic party – or more specifically, to the Democratic County Central Committee. In an 1859 editorial, he warned readers to be wary of fake Democrats:

| There are hordes of hungry, disappointed office seekers, who, caring more for the loaves and fishes, than for either the people or the party, when they find their aims are defeated will not hesitate to become “Independent Democratic,” or “Douglas Democratic,” or “Squatter Democratic” candidates, for the purpose of breaking down the party. Beware of them. They are “wolves in the clothing of the gentle lamb,” and may be found in all parts of the country. |

Whatever his true political leanings, in April 1860 he sold the works to firebrand Thomas L. Thompson, who would never leave any doubt about where he stood. The Sonoma Democrat became a loathsome soapbox advocating for the Confederacy and against Lincoln and the Union in whole.

– –

DOWNLOAD sources discussed in this articleI’ve been informed that subscribers who read SantaRosaHistory.com on mobile devices were having problems accessing this article because of its original large size, which was due to the transcribed source material. All of that content has now been moved into a 50 page PDF file.