Hours before dawn, the boys were gathering at the depot waiting for the circus train. They would be playing hooky that day but wouldn’t get into much trouble for it; after all, their fathers did the same thing (and maybe grandfathers, too) and they had heard their elders speak wistfully about the pleasure of it, waiting in the dark with a swarm of kids and grown men for the trainload of marvels speeding their way on the rails.

From the 1916 Argus-Courier: “A monster train of red cars, loaded to the guards with circus paraphernalia and equipment of the John Robinson ten big combined shows, the oldest circus in the world, reached Petaluma Thursday morning, a little late but all safe and sound. There was a good sized reception committee on hand to welcome the showmen. Some were there who declared they had not missed seeing a circus ‘come in’ in twenty years. A few even remembered the last time the John Robinson circus visited California 35 years ago. Some small boys were at the depot as early as 3 a. m. although the circus did not arrive until 8:30.”

Setup in Santa Rosa was easier than many towns, where the fairgrounds were usually outside city limits and far from the depot. Here the show lot was nearly in the center of town – the former grounds of the old Pacific Methodist College (now the location of Santa Rosa Middle School, between E street and Brookwood Ave). Once the college buildings were removed around 1892, the nine acre vacant lot became the temporary home of every show rolling through.

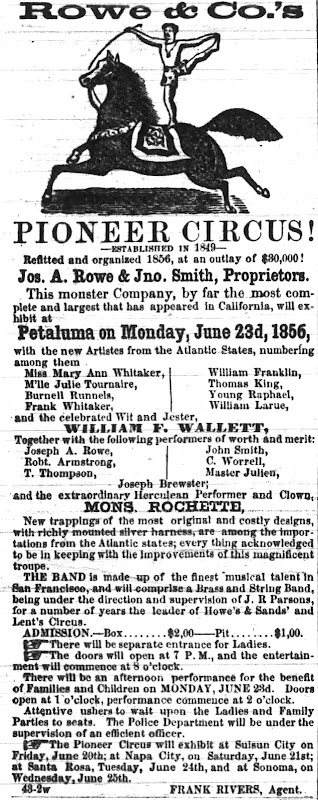

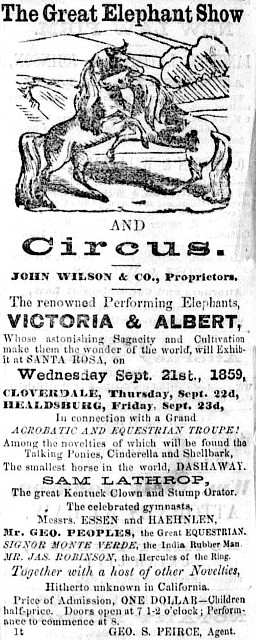

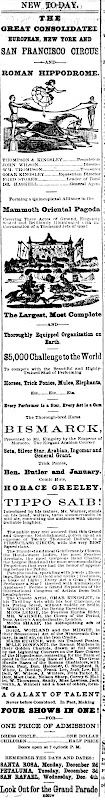

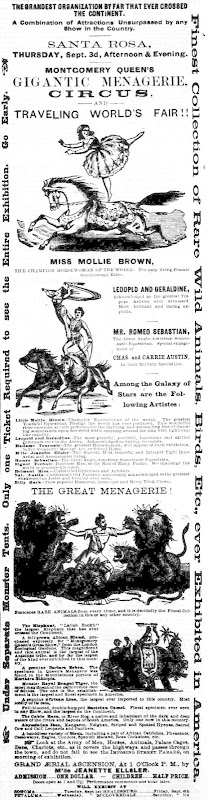

This is the second item about the circuses that came to Santa Rosa and Petaluma as viewed through our local newspapers. Part one, “WHEN THE CIRCUS WAGONS CAME TO TOWN,” looked at the shows before the railroads arrived in the 1870s. With trains available the bigger and more famous circus companies began to come here and by the early 1900s, Santa Rosa could expect a visit from a world-class circus every year. The shows discussed below are only a small sample.

A big attraction for the 1883 John Robinson’s Circus was the electric light “as bright as the noon-day sun.” For advance PR they sent newspapers a humor column about “Uncle Jerry Peckum” complaining the “sarkis” tent being too close to his chicken farm: “It’s lit up so brite thet every last one o’ them tarnal fool chickins thinks it’s daylite again’, an’ got up an’ gone to layin.'” The column ended with Jerry deciding to go to the circus because “I’ve heern so much about this ‘lectricity light–an’ we may never hev a chance to see one agin.” The promo piece ran in the Petaluma Argus, naturally, because chicken.

|

| 1883 John Robinson’s Circus |

The 1886 Sells Brothers Circus was the first mega-show to visit Sonoma County. While both Petaluma and Santa Rosa newspapers raved about its quality, the Petaluma Argus was outraged admission at the gate was $1.10 instead of the traditional buck.

Speaking of ripoffs: Earlier the Santa Rosa Daily Democrat ran an amusing reprint from a New York paper describing the predator/prey relationship between a circus “candy butcher” (food vendor) and the locals: “…The candy butchers in a circus never work the bottom row of seats. Country bumpkins who easily become their prey always get up on the top benches. They do this because they are afraid of the ‘butchers’ and want to hide from them. The latter move around on the top seats, and when they find a verdant fellow they fill his girl’s lap with oranges, candy, popcorn and fans. If the girl says she doesn’t want them they ask her why she took them, and make the young man pay thirteen or fourteen prices for the rubbish…” The piece continued by describing the pink in a circus’ trademark pink lemonade was a red dye added to conceal how little lemon actually was in the drink: “Strawberry lemonade men make two barrels of the delicious beverage which they sell of ten cents worth of tartaric acid and five cents worth of aniline and two lemons. They make fifty dollars a day each…”

|

| 1886 Sells Brothers Circus |

I’m sure it lived up to its claim of being the “greatest show on earth,” but when the Ringling Brothers Circus made four visits during the 1900s we were flooded each time with the greatest hype on earth, as the Press Democrat seemingly printed every scrap of PR flackery the advance promoters churned out as “news” articles. “The aerial features of Ringling Brothers shows by far surpass anything of a similar nature ever exhibited in the United States. The civilized countries of the world have been thoroughly searched for the newest and most thrilling acts.” (1903) “Their Acts in Ringling Brothers’ Circus Almost Surpasses the Possible.” (1904) The low point was probably the 1907 article, “Interesting Facts Regarding the Expense of Advertising and Maintaining a Great Circus,” which was neither very interesting nor very factual: “An elephant without plenty of feed is as dangerous as a healthy stick of dynamite.” Yowp!

|

| 1900 Ringling Brothers Circus |

Santa Rosa schools were dismissed at 11AM on the Thursday morning when Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show came to town, which was a pragmatic surrender of any hope for keeping the kids at their desks once the parade started marching down Fourth street.

There was no Big Top for this show, just a horseshoe-shaped grandstand that could seat 16,000. The audience was apparently immense; the PD reported, “afternoon and evening the vast seating accommodations was occupied with a sea of humanity.”

These 1902 performances were not Buffalo Bill’s “last and only” shows in Santa Rosa. He was back again in 1910 for his “farewell tour,” and also in 1914, after he lost the legal use of the “Buffalo Bill” name and had to perform with the Sells-Floto Circus. For more, see “BUFFALO BILL STOPS BY TO SAY GOODBYE.”

|

| 1902 Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show |

“Early in the day farmers from far and near came driving to town with their entire families while special trains brought crowds from points as far away as Ukiah,” reported the Press Democrat in 1904 about the third appearance here by the Ringling Brothers Circus. “By 11 o’clock the streets were thronged with a good natured perspiring crowd prepared to be amused at any thing.”

Unfortunately, Santa Rosa was suffering through a heat wave that September morning: “The Court House proved a very attractive place as it was so cool and refreshing within its walls while outside the thermometer ranged from 100 upward from 10 o’clock. Many of the windows were filled with the families and friends of the county officials, while the steps and shady portions of the grounds were packed with outside visitors. All along the line of march all available windows and other points of vantage were packed, while great throngs moved restlessly up and down the principal streets, and crowded the stores.”

The description of the circus parade was probably rewrite of PR copy, but it’s still fun to imagine a sight like this coming down Fourth street: “Never before in the history of Santa Rosa has there been such a parade as Ringling Bros, gave Thursday. Floats and chariots, half a dozen bands, numerous companies of horseback riders representing various nationalities, both men and women, a drove of thirteen camels, twenty-six elephants and many open cages of wild animals. Altogether there were over 375 horses in the parade. They were ridden, driven two and three tandem, in teams of two,. four, six, eight and twenty-four horses each. One of the most pleasing sights to the younger people were the twenty-four horse team on the band wagon and the twenty-four Shetland pony team on a float.”

|

| 1905 Press Democrat cartoon: “In Town for the Circus” |

Norris & Rowe’s Circus was a Santa Rosa favorite in the first decade of the Twentieth Century, and not just because they reliably showed up every April. “On account of the fact that it is a California show,” explained the Press Democrat in 1905, “the people of this state are naturally interested in its success from year to year, and the enterprise of Norris & Rowe in having advanced in a few years from a small dog and pony show to the growing circus that they now possess, has been highly commended.”

Alas, the show had no end of problems, well symbolized by the photo below showing their 1905 “Grand Gold Glittering Street Parade” in Santa Rosa taking place during a downpour. Their last appearance here in 1909 shocked some by offering “several gambling schemes” and a racy sideshow “for men only.” The circus went bankrupt and closed in 1910. For more see: “BROKE DOWN CIRCUS.”

|

| Photo courtesy Sonoma County Library |

The Barnum and Bailey Circus made its second stop here in 1908, and the show was the biggest, best, blah, blah, blah. This trip was notable for an acrobatic act which sounds genuinely risky; the odd-but-colorful description that appeared in the Press Democrat is transcribed below (and was undoubtedly circus PR) but from other papers we can piece together what really went on.

The main performer was 20 year-old Yvone La Raque, who was seated in an “automobile” at the top of a narrow ramp near the top of the tent, about 65 feet in the air. (I can find no claim the little vehicle actually had an engine.) When her cart was released it dropped down the ramp and flew off with enough speed to somehow execute a somersault. She and the little car landed on a separate spring-cushioned ramp several feet away. The entire business took only 4-5 seconds.

Now, Gentle Reader might not think this such a great challenge; all she had to do was keep the wheels absolutely straight and do whatever weight-shifting physics needed to perform the loop-de-loop. But that was in 1907-1908, an age when steering wheels regularly fell off because gearboxes were still an experimental thing and even the best new tires sometimes burst under stress. And, of course, success depended upon workers quickly setting up the landing ramp with absolute precision while circus craziness was underway.

That was 1907 when Yvone was a solo act with a different circus; when she joined Barnum and Bailey her sister (name unknown) was added to the act, following her immediately down the ramp in an identical car and flying across to the landing ramp while Yvone looped above her. By all accounts the crowds went nuts.

I researched them with dread, certain I would discover one or both were killed or horribly mangled, but apparently they retired uninjured at the close of the 1908 season.

The start of this awful act is made from the dome of the tent. The cars ride on the same platform, one behind the other, being released simultaneously. One car is red and the other blue that their separate flights may be followed by the eye that dares to look. The leading auto arches gracefully across a wide gap, being encircled as it does so by the rear car. They land at the same instant. From the time the cars are released at the top of the incline to the landing below on the platform, Just four seconds elapse. Those who have seen the act say it amounts to four years when you figure the suspense, the worry and the awful jolting of the nerves. “You feel like a murderer waiting for the verdict,” says some one who saw the act while the circus was it New York City. “The suspense is awful. You look back over your past life. You regret as many of your sins as you can it four seconds. You want to close your eyes, but you can’t. My, what a relief when they land safely! That’s the jury bringing in a verdict of not guilty. Then you rise with a yell of joy as the young women alight without a scratch. Everybody else yells. Oh, it’s great!”

|

| 1908 Barnum and Bailey Circus |

And finally we come to the Al G. Barnes Circus. The ad below is from 1921, but his show first appeared in Santa Rosa ten years earlier. I deeply regret having not found much about him beyond a few anecdotes – he clearly was gifted with a rare magnetic personality and both people and animals were drawn to him instinctively. His friend and attorney Wallace Ware tells the story of seeing Barnes throw meat to a fox in a forest, then approaching the wild animal and petting it as if it were tamed. He trained performing animals with food rewards but also by talking to them with genuine sincerity as if they could understand everything he said. Ware’s memoir, “The Unforgettables,” has a section on Al worth reading if you’d like to know more.

(RIGHT: Chevrolet and bear at the Al G. Barnes Zoo, Culver City, 1926. Courtesy of the USC Digital Library)

(RIGHT: Chevrolet and bear at the Al G. Barnes Zoo, Culver City, 1926. Courtesy of the USC Digital Library)

Barnes also had a private zoo near Los Angeles where he kept animals too old or too wild to be in the circus. It must have been enormously expensive to maintain – supposedly it numbered around 4,000 animals – but kudos to him for not destroying the unprofitable animals or selling them off to carnivals where they likely would suffer great abuses. That was the 1920s, remember; there were no animal sanctuaries for former circus animals, tame or no, and trade newspapers like Billboard and the New York Clipper regularly had want ads of circus animals for sale.

The Press Democrat treated him like a hometown boy although he was from Canada and lived in Southern California when he wasn’t touring. The PD reprinted news items about his circus, his illnesses and reported his marriage on the front page. When he died in 1931 the PD wrote its own obit: “When Al G. Barnes rode into the ring, swept off his hat, bowed and welcomed the crowd, you knew who was running the show…his death will be generally regretted, not only in a personal way but because it marks the passing of a picturesque character, one well known in the west–one of the last of the kind.”

|

| 1921 Al G. Barnes Circus |