A new era is here! Americans are embracing the revolutionary “sharing economy” where we sell everything to each other directly. We shop in an unlimited marketplace with fair goods at fair prices and delivered right to our door free (or fairly so). To roughly rework Miranda’s lines in Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “Oh, wonder! How many consumers are there here! How beauteous sellers are! O brave new world, That has such people in ‘t!” Of course, then her world-weary father, Prospero, pops her bubble and replies simply, “Tis new to thee.”

Prospero could have been thinking of the even braver new world which dawned on New Year’s Day, 1913. Now for the first time you could send a package to anyone in America, no matter how remote or distant – and the person at that place could send a package to you as well. It is probably impossible for any American alive today to appreciate what this meant to a nation which was still mostly rural, and equally hard now to understand why it was such a controversial idea at the time.

(Detail of cartoon from the San Francisco Call, January 5, 1913)

(Detail of cartoon from the San Francisco Call, January 5, 1913)

The service was parcel post and our great-grandparents enthusiastically began mailing stuff to each other immediately. The volume of mail at the San Francisco post office doubled the first day, the Call newspaper reported, and that was even before any trains arrived with parcels from outside the Bay Area.

At the start a package could weigh only eleven pounds max (the limit would soon be bumped to twenty) and there was a long list of items you couldn’t mail, particularly booze, animals alive or dead, guns, or things that might explode or stink. But the early days were somewhat chaotic, in part because there was circulating another, shorter list of forbidden items with live poultry being the only specified animal. There were also jokesters trying to mail silly things and get them mentioned in the paper – bricks addressed to Postmaster General Burleson were a favorite. “The most popular American toy today is the parcel post,” commented the Brooklyn Eagle. “Everybody in the land seems to be playing with it.” Gag items sent in the first week included a woman’s hat, a snow shovel, a tarantula in a little cage, a coffin split into two parts and eggs that hatched en route, as intended. Skunk pelts were reported in Kansas, Pennsylvania and Arizona, while someone from Sonoma county sent a large Burbank potato with the address carved in it.

The Postmaster General issued a clarified set of rules at the end of the month – meat was no longer a “dead animal” – and the postal service settled into being a delivery service, hiring thousands of new workers. People came to expect parcel post being available from every sort of local business. If you lived in Cloverdale, for example, you could mail dirty clothes to a Santa Rosa laundry. You could get a freshly-killed turkey from Petaluma and order a fancy cake from a Sonoma square bakery.

Parcel post was cheap but if the sender and recipient were both in the “local zone” – meaning their mail carriers worked out of the same post office – it was nearly free: 5¢ for the first pound, up to 24¢ for the maximum 20 pounds (the weight limit went up to 50 pounds the following year). In the middle of 1913 the post office introduced C.O.D. so you no longer even had to pay for something until it arrived.

If that was the extent of Parcel Post, it still would have been a dramatic shift in the lives of most Americans. There was now a pipeline to their home from virtually any store or service; no longer was home shopping limited to what was offered from Sears and Montgomery Wards mail-order catalogs. But the revolutionary aspect of the service was that the pipeline flowed both ways – farmers could now sell direct to the consumers and bypass all middlemen, and sell they did: A mainstay of parcel post deliveries in those years were farm-fresh eggs, butter and lard. (Pictures of an egg mailing carton here.)

But the postal involvement didn’t end there. Rural mail carriers collected lists of which farmers had what to sell and copies were stuffed in mailboxes of city dwellers, as well as posted at public libraries. In 1914 they launched a farm-to-table movement – and yes, they called it a “movement” – that term was not an invention of foodie hipsters. At the same time on the urban front, women’s groups such as the National Housewives’ League promoted neighborhood collectives to manage bulk buying and handle storage of perishables, as few home kitchens had refrigeration.

These years just before WWI were probably the closest America ever came to achieving Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an agrarian republic, with town and country joined in harmony (or at least, in some places). But none of it would have happened had not the federal government done a bold and subversive thing by going into direct competition with a major private industry.

Prior to 1913 if you wanted to send a package to cousin Polly in Poughkeepsie you took it to an express office. There were about 30,000 offices across the country; if a hamlet was really small, it usually doubled as the telegraph office. It wasn’t a bad system for shipping stuff long distances, but the first problem was what happened when the parcel arrived. The express companies weren’t in the home delivery business; if your address wasn’t on their routes, the package would likely wait at the Poughkeepsie office until your cousin came in to pick it up. By contrast, the post office had a well-established mail delivery system nationwide with routes covering five times more mileage; the mailman was already going to Polly’s door once or twice a day anyway. The second problem with the express companies were their rates. Everyone griped they charged too much, but nothing was ever done; when Congressional hearings on parcel post began in 1911, the latest investigation by Interstate Commerce Commission had been going on for nearly two years.

We can thank Oregon Senator Jonathan Bourne, Jr., a progressive Republican in the vein of Teddy Roosevelt, for the creation of parcel post and all that followed. He might have been a swell fellow, but he could not chair a public meeting. If you’re a masochist with about ten hours to lose, read all eight days of Senate hearings and marvel at how often they get lost in the weeds. My favorite moment is when a guy tells the Senators, apropos of nothing, that “Brain and Personality” was the greatest book about the human mind published in the previous 25 years (spoiler alert: No).

Sparing Gentle Reader that ordeal, the testimony can be summarized as wildly contradictory. Parcel post would doom little country stores or parcel post would be a boon to little country stores. It was a giveaway to Sears and other big mail-order houses or it was a giveaway to the farmers. It was un-American to compete with the express companies or it didn’t go far enough and the government should take over the express companies. It was a big step towards socialism or it was an overdue step to help reduce the cost of living for workers. It would bust the post office budget (which only recently had wiped out a big deficit) and plunge it deeply into the red or it might possibly make a profit.

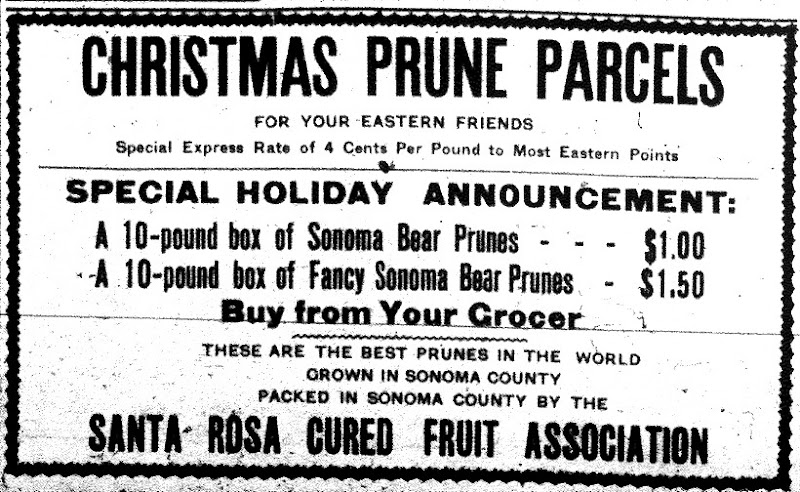

To the astonishment of nearly everyone, as the end of 1913 approached it was reported parcel post had turned a whopping $30 million profit. Other benefits of that year’s success included the express companies lowering rates and offering new farmer-friendly services. The ad below for “Christmas Prunes” was a deal intended to be sent via parcel post, according to an item in the Pacific Rural Press, but apparently an express company jumped in with a more competitive offer.

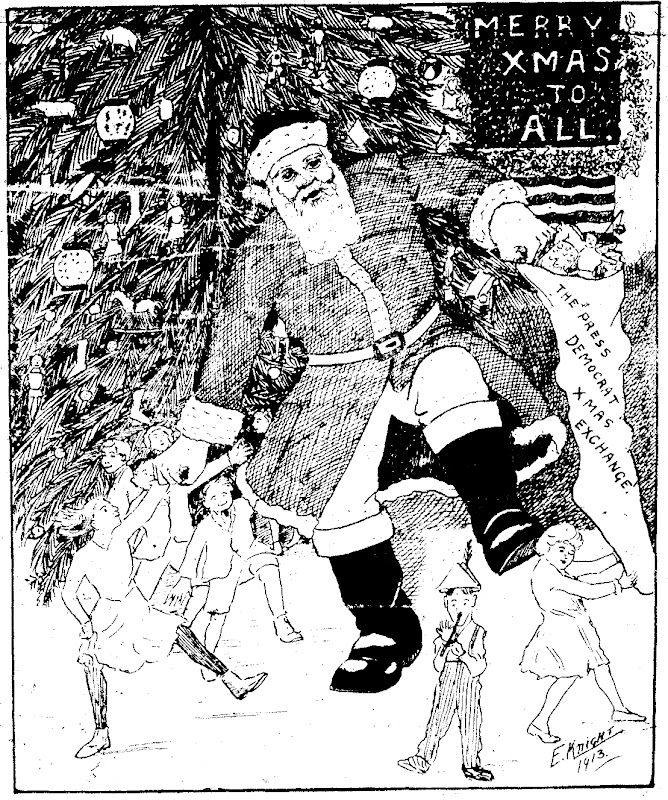

(Oakland Tribune cartoon Dec. 22, 1913)

(Oakland Tribune cartoon Dec. 22, 1913)

But before the post office could take a victory lap, it had to survive the tsunami.

Everyone loved parcel post so much they felt empowered to send gifts to all their Christmas card relatives – Aunt Irma, Uncle Herb, Cousins Willy and Mabel and Edith and her husband Sid and everyone’s little ones whom they knew only by name. So enormous was the volume of parcel post mail in the week before Christmas that every day set a new all-time post office record over the day before. “There is always a great volume of mail around Christmas time,” a December 20 wire service story reported, “and this year, with the added task of handling hundreds of thousands of parcel post packages, the offices in the larger cities would have been hopelessly swamped but for emergency measures.” Efforts to cope with the unending piles of parcels were epic and it became a major news story, with several papers offering cartoons such as the one seen here; another popular variation showed an express company driver having a good laugh at the poor mailman’s misery.

The obl. Believe-it-or-not! epilogue to the launch of parcel post came a few weeks after Christmas, when May Pierstorff’s mother glued stamps to her five year-old’s coat and parcel posted the child to her grandparents 73 miles away. Because she was just under the new fifty pound weight limit, postage was 53 cents.

She wasn’t the first child to be mailed nor was she the last, although the newspaper stories about these kids always mentioned it was against the rules to send people through Parcel Post. But guess what: That wasn’t true – unless you counted the regulation that “meat may not be shipped through more than two parcel post zones.” It wasn’t until June, 1920 before the post office decreed no humans could be shipped in the mail regardless of weight, inspiring the bestest headline that ever appeared on the front page of the New York Times: “Rules Children Cannot Be Sent by Parcel Post as Live Animals.”