This would be a nice weekend to put some flowers on the grave of your Great-Great Aunt Virginia, who passed away during the Spanish Flu pandemic – so grab some posies and trek over to where she was buried in 1918. Is she still there? Why, yes. A cemetery is a place with people who generally don’t move around much. This is widely considered to be a good thing.

Should you find yourself lost in the cemetery, there’s usually an office (or at least a telephone number) where someone can direct you to Aunt Ginny’s most permanent address. That helpful person would have little trouble finding her because the major cemeteries in central Sonoma county have a map and a master index of names. Sometimes very old records might not be perfect, but overall the picture of who’s located where would be still mostly complete (see sidebar). The sad exception was always Santa Rosa’s Rural Cemetery.

At some point in the early 20th century the burial listing book for Rural was lost. Or maybe it never existed – there’s no proof it did, although it’s difficult to imagine how the historic cemetery could have functioned otherwise. If Virginia was supposed to be buried in the family plot, it would be a really good idea for the mortician to know exactly where to dig.

So the ultimate mystery of Santa Rosa’s Rural Cemetery centers on discovering how all its records were destroyed, and when – but until that can be answered (if ever) the adventure lies in trying to recreate the burial listing book.

Efforts have been ongoing for nearly a century, and finally in 2021 we have a version that is both rigorously fact-checked and includes far, far more long forgotten burials. For more background on this new book see the interviews with co-authors Sandy Frary and Ray Owen.

Efforts have been ongoing for nearly a century, and finally in 2021 we have a version that is both rigorously fact-checked and includes far, far more long forgotten burials. For more background on this new book see the interviews with co-authors Sandy Frary and Ray Owen.

What follows are the stories of all the versions that came before. This might seem to be a real snoozer of a topic but along the way Gentle Reader is going to meet several interesting people making heroic efforts to save our history, and we can never read that story often enough.

In each case, a team of volunteers dedicated years to chasing what had been recorded in the original book; that their final product was flawed is not due to anyone’s lack of effort or commitment. As explored in the interviews, the new edition is so much more successful because Sandy and Ray brought along investigative skills and had access to previously unavailable primary source materials. They also spent nearly fourteen years, longer than any other team.

Ray and Sandy additionally had a significant advantage in the cemetery being in its best shape…since ever. The previous article “A CEMETERY SO LONG UNCARED FOR” documents the shameful condition it was in until serious restoration work finally began in the late 1990s. The earlier project volunteers deserve enormous respect and sympathy for pursuing their research despite having to claw through thick underbrush – including poison oak – to simply read what appeared on grave markers.

The first group to do a field survey of Rural was the Santa Rosa Chapter of the D.A.R. in 1934-1941. In that era the Daughters of the American Revolution were better known for venerating their ancestors at Colonial-themed soirées and pushing über-patriotic “Americanism” school programs, but the state D.A.R. also took seriously George Washington’s call for institutions to promote the “general diffusion of knowledge.” Their good works included transcribing the 1852 California census and doing cemetery surveys “…so that if the graves are lost, the records will still be preserved,” as the Press Democrat explained. And they didn’t just tackle the Rural Cemetery – they collected names from all 90 graveyards in the county (there are now about 130 known to exist).

The driving force in the local D.A.R. cemetery efforts were sisters Pauline Olson and Edith Merritt. Pauline had worked for Luther Burbank for a few years both as a secretary and operator of the “Bureau of Information” kiosk on Santa Rosa Ave. which kept Burbank-curious tourists from pestering him. When their research was finished in 1941, she typed up five copies of the entire 320 page book, which must earn her a Believe-it-or-Not! honorable mention. (The D.A.R. paid for the paper, the typing, and hopefully the linament for her aching wrists and fingers.)

Edith Merritt had a deep interest in local history. She was a popular speaker on the topic at women’s clubs and in 1925 directed the Native Sons club in placing signboards at significant historic landmarks around the county. She and husband Edson C. Merritt lived at the beautiful Craftsman style house at 724 Monroe Street (which still exists) and it was there that she and Pauline hosted a 1905 Goth-like “Ghost Party” which had people still buzzing about it months later.

| – | – |

|

Surely the D.A.R. researchers would have referred to the burial listing book for Rural if it still existed as the project continued through the 1930s, but the only outside sources they credit in the preface are newspaper death notices for burials prior to the Civil War. At the end of this piece I offer a theory that the listing book disappeared in that decade and what I believe might have happened to it.

The 1930s also saw the end of the Rural Cemetery Association, which is discussed in greater depth in the previous article. Although their corporation legally ceased to exist in 1916, they continued selling private deeds to burial plots. Finally in 1938, Santa Rosa came to recognize a harsh truth, as a Press Democrat editorial commented: “Rural cemetery is now and for years past has been an abandoned child…Nobody owns Rural cemetery.”

The 25 years that followed were the darkest in the history of the cemetery. Aside from a disastrous 1951 “controlled burn” there were no efforts at cleanup (much less maintenance) and it grew into an urban jungle. Even worse, the defunct Association had left a poisonous legacy by convincing the town that every grave plot was private property and not a weed could be pulled without explicit permission from descendants.1

The turnaround began after Sara Laughlin was buried there in 1963. When the family tried to visit her grave the trails were so overgrown they could barely get through, so Sara’s 25 year-old grandson Jay McMullen started bringing up a lawnmower on weekends and clearing the roads. Soon his mother, Evelyn McMullen, was joining him in their unofficial cemetery caretaking.

Word spread of what they were doing and others pitched in, with sometimes up to twenty people joining Evelyn’s volunteer crews. In 1965 she and others formed a new Cemetery Association as an affiliate of the Sonoma County Historical Society. The goal was not to claim ownership and sell grave plots but to collect $1/yr. dues – enough to pay for trail gravel.

As the McMullens became known for their cemetery smarts, people began calling them to ask where someone was buried – although it’s doubtful they were able to help that much, as they were going on only their personal experience and the D.A.R. book at the library. And that led to the creation of the “Greenwood Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery” map.

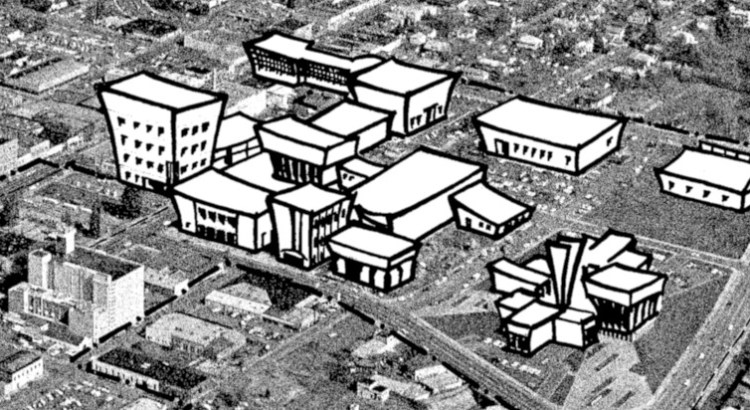

Trained as an architect, Jay began making a hand-drawn map which measures about 3×4 feet. He finished around 1968. Although there are technically four cemeteries there, he grouped them all together as Greenwood – which like “Rural,” was often a generic cemetery name during the Victorian era in America. (Jay said there was a reference to the name being used in Santa Rosa, but nothing can be found in the old newspapers.)

At least three photocopies were made but there’s no evidence Jay ever intended to publish his rough map – it seems that it was just a guide to help those who called the McMullens and maybe a reference tool for volunteer workers. And he added every scrap of information he and Evelyn could find, including records of plot deeds from the recorder’s office. (The map includes handwriting by at least one other person.)

In 2015 Sandy Frary, Ray Owen and I took an iPad with Jay’s map to a small section of the cemetery, hoping to determine if tombstones had been lost in the last 55-odd years, whether there were markers for unrecorded burials, and the like. Alas, Jay’s inclusiveness proved to make it a mostly futile exercise.

In 2015 Sandy Frary, Ray Owen and I took an iPad with Jay’s map to a small section of the cemetery, hoping to determine if tombstones had been lost in the last 55-odd years, whether there were markers for unrecorded burials, and the like. Alas, Jay’s inclusiveness proved to make it a mostly futile exercise.

As shown at right, the entries marked in red were not found. But we don’t know whether the McMullens saw a marker there in the 1960s or not; the grave could have been purchased from the Association and had the deed registered, but ended up never used. (Sandy was later able to determine that four were buried elsewhere.)2 Or maybe the person is at the indicated place, but the family didn’t want to spend money on a tombstone. There are many possibilities.

Yes, it would have been historically more valuable if the McMullens had only recorded what they actually saw, but there’s still a usefulness in knowing someone might be buried at a particular place. Future historians will find it a valuable resource as long as they keep in mind that a percentage of the entries are paper ghosts.

The McMullen volunteers stopped volunteering as the 1960s came to a close and despite support from the Madrone Audubon Society, the McMullen era was over. Weeds began taking over again and that was the least of the problems. In 1980 vandals were driving 4WD vehicles into the cemetery and using winches and cables to topple large monuments. Someone broke into the holding vault where the cremains of the indigent were stored, dumping the ashes on the floor.

The year before Santa Rosa had declared ownership of the cemetery via eminent domain, but allocated no funds to pay for anything; it was left to the Board of Community Services to fundraise for building a gate and a fence. Nanci Burton – who became a member of the Santa Rosa City Council and mayor later in the decade – led the new cleanup projects. At an April 1980 work session, an estimated 325 volunteers turned out.

The Genealogical Society also pitched in to search out descendants of those buried at Rural. The Society had already published a 1977 second edition of the D.A.R. book with some corrections and additions so it should come as no surprise they decided to use their research skills to produce a book of their own.

And so began the search for the last lost graves. Their list of sources in appendix I is impressive – the Society built a card catalog starting with the D.A.R. material and what they could find in the legacy records of every local funeral home. They copied tombstone receipts from the North Bay Monument Company. They examined death certificates through 1905. They combed through all the deed books. They absorbed all the information that Evelyn McMullen had collected over the years. What the Genealogical Society published in 1987 was an impressive work of scholarship at the highest standards – but it was still far from complete.

As told in the last article, the renaissance of the Rural Cemetery began in 1994 when Bill Montgomery from Recreation & Parks formed a Restoration Committee. Among those volunteers were Margaret and Alan Phinney.

Alan and others did the heavy work that no one had attempted before – relifting fallen tombstones and monuments. (Like buttered bread, it seemed that tombstones always fell face down.) Sometimes the markers had to be pieced back together like giant marble jigsaw puzzles.

The Genealogical Society gave Margaret Phinney the old floppy disks with the text files used to create their 1987 book, which she imported into a database where entries could be easily updated or added.

The database proved critical because new information was pouring in. Members of the Committee and the Society joined in creating the first comprehensive row-by-row field survey, and the Phinneys were feeding Ray Owen a steady list of names needing research. By the time the next edition of the burial listing book was published in 1997, about five hundred names had been added. The 2007 update contained further additions and corrections.

And that brings us, more or less, to today. The Phinneys handed the database over to Sandy Frary, who with co-author Ray Owen has now published the new, exhaustively researched 2021 edition. While there are bound to be some lost graves still to turn up, the numbers should be vanishingly small compared to the 5,515 burials that are now documented.

So what did happen to the original burial records? It’s sometimes said they must have been lost in the 1906 earthquake and fire, but the last recorded sale of a burial plot by the old Association was May 1930, so it’s a safe bet the book (or books) still then existed. My working theory is that it was lost due to some mishandling accident between the D.A.R. and board members of the Rural Cemetery Association.

The local D.A.R. chapter began work in Sonoma county in 1934, although the state organization in Sacramento had launched the project two years earlier. As the headquarters were set up to copy historical records – as per their transcription of the 1852 census – it seems quite likely they would have asked to borrow the burial listing book to make a copy. A search for correspondence with the Association between 1932-1934 in the D.A.R. archives would definitely be worth a look.

I am haunted by a comment made years later, at a 1951 Chamber of Commerce meeting on what to do about awful conditions at the cemetery. The county recorder speculated (or had been told?) that the burial listings were lost because “records were passed around until finally they all disappeared.”

The book with those records was one of the most important documents in Santa Rosa history, so it’s tempting to believe it must have been destroyed in a dramatic event, such as a catastrophic fire. Surely it couldn’t have been simply lost in the mail, or left behind on a Sacramento city bus.

| 1 The Rural Cemetery Association sold private deeds, but it is unclear whether that included property title. The Cypress Hill cemetery is adamant that their deeds only bestowed burial rights. California laws regarding cemetery corporations left the definition of grave ownership to the bylaws of the corporation, aside from whatever rights of the deed holder becoming “forever inalienable” once there was an interment. The Rural Cemetery Association did not record the deeds they sold with the county, although some people did so at the recorder’s office on their own. |

| 2 Details of Eastern Half Circle survey compared to the Jay McMullen map: Of the twenty map entries where no marker was found in 2015, it was decided half were likely to be buried in the indicated plot; four were either known or very likely to be buried elsewhere; and six had no matching name in the county’s Vital Statistic Death Index, which suggests either the person died outside of Sonoma county or the name on the map is incorrect. |

Apr 26 1922; Mrs. Frank C. Newman president of association

Nov 5 1932; D.A.R. begins

Oct 24 1934; D.A.R. work

Apr 28 1937; Cemetery Association last election

Feb 26 1941; D.A.R. done

Dec 24 1950; D.A.R. book presentation

Mar 28 1951; records were passed around

Apr 7 1965; McMullen Cemetery Association formed

Mar 29 1966; McMullen Cemetery Association 1st annual meet

Apr 26 1966; McMullen map has 1000 names

Aug 3 1969; McMullen Association cleanup work

Aug 17 1969; new incorporation

Sep 19 1977; full page foto spread

Jun 1 1979; Gaye Lebaron on McMullen Association

Jan 11 1980; Gaye Lebaron on eminent domain and vandalism

Feb 24 1980; vandalism of cremains

Jun 2 1980; fence fundraiser