[Editor’s note: You might really be looking for “THE FORGOTTEN GREAT FIRE OF 1870” which describes there was a third firestorm identical to the Tubbs/Nuns Fires which has never been mentioned]

Could this fire happen again? That’s the multi-billion dollar question hanging over everyone who lost homes in Fountaingrove and Coffey Park as they weigh the decision on whether or not to rebuild. There are no good answers; we can’t even be sure our guesses are reasonably good. There’s just too much we don’t know about the world’s changing climate to say this was a freak event or the harbinger of a new terrible normal.

To understand more, I urge everyone to read (or at least, skim) “The Real Story Behind the California Wildfires” by Seattle meteorologist Cliff Mass. He makes several important observations I’ve not seen mentioned elsewhere, particularly that there were hurricane force winds (96 MPH!) at higher elevations before the fire began to spread. The speed of those winds are unprecedented in our neck of the woods and were a significant factor in creating what he calls a “unique mountain-wave windstorm.” Again, it’s a must-read.

Comparisons are being made to the September 1964 Hanly Fire (that’s the correct spelling, not “Hanley”) which burned over the same route – Calistoga to Franz Valley to Mark West Canyon and then driven down into Santa Rosa, likewise by the powerful, unrelenting “Diablo Winds” on a Sunday night. But it did not grow into the hellish firestorm that raged in 2017; it was stopped on Mendocino avenue just outside the now-lost Journey’s End trailer park.

But forgotten since are the two other major fires specific to Fountaingrove and the Coffey Park areas. Each was the most serious fire of that year in Santa Rosa. It just may be a coincidence that these incidents were at the same locations, but at this point, any additional information about our fire history is good to have.

Major factory fires threatened Santa Rosa’s industrial rim in 1909 and again in 1910, but of all the fires in Santa Rosa history, the Fountaingrove fire of 1908 was the one which might have burned down the town.

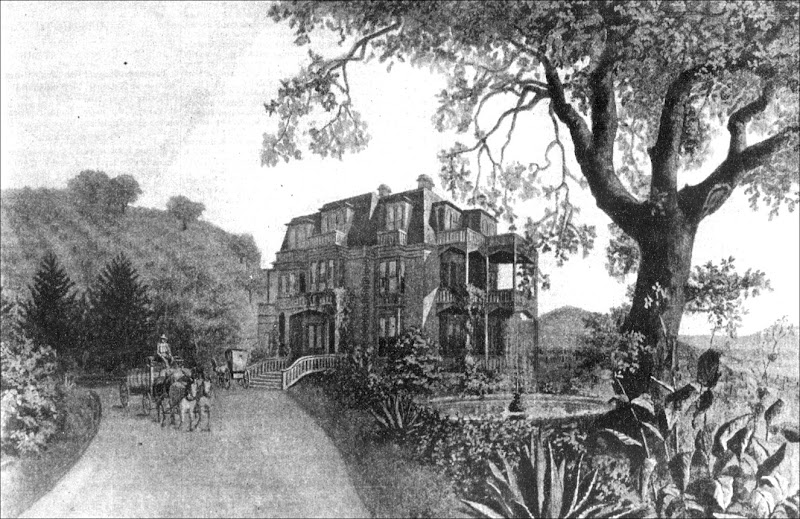

The fire was huge, easily visible from Healdsburg because it was nearly at the top of the hill. In flames was the landmark “Commandery,” one of the main buildings from the heyday of the utopian colony founded by Thomas Lake Harris. That was the residence for the colony’s men. The fire began when a kerosene lamp exploded, destroying the place so fast that nothing in the three-story mansion could be saved.

“Fortunately the north wind that had been blowing earlier in the day and evening died down, otherwise the flames would have spread,” the Press Democrat reported at the time. From a high ridge like that, just a stiff breeze could have easily thrown embers a mile and a half downwind to the county hospital on (the road later named) Chanate – which also came within 100 yards of burning in the 1964 Hanly Fire (and where a developer now has the go-ahead to build a dense subdivision of up to 800 units).

The fire burned itself out quickly; it’s not clear if the Santa Rosa Fire Department did anything. A pasture also ignited and was easily handled. But had a northern wind still been gusting, firebrands from the Commandery might have blown as far as the core neighborhoods across from the modern-day high school, where almost all Victorian homes had shingle roofs.

While Santa Rosa got a lucky break in 1908, Fortuna did not smile as much on the town in 1939, when a wind-whipped fire swept across 500 acres in (what would become) the Coffey Park neighborhood.

That September 20 fire started at the airport. Today probably only the oldest-timers and aviation buffs know that the town had an airport there; when it opened in 1929 it was first called the Santa Rosa Municipal Airport, then it became the Santa Rosa Airpark and lastly the Coddingtown Airport, which finally closed in 1971 or 1972 (EDIT: The Airpark and Coddingtown were nearby, but not the same place). The layout of the runways shifted over the years but the way it probably looked at the time of the fire can be seen in the graphic below. (For much more on all the historic airfields in the Santa Rosa area, see the “Abandoned and Little-Known Airfields” site. Don’t miss the commemorative postmark of Luther Burbank looking like an angry muppet.)

|

| Approximate location of the Santa Rosa Municipal Airport runways in 1939 |

The airport fire was completely avoidable, and if not for the serious danger it posed would serve as the script for a Keystone Kops slapstick comedy.

It was the hottest day of the year, with the thermometer reading 104 – hardly conditions to do weed burning, but that’s what a crew of 10-12 men were doing that afternoon on the runways, dragging burning rags behind a truck.

They were working in the southwestern end of the field when the wind suddenly started blowing from the south, sending the fire towards the modern intersection of Coffey Lane and Hopper Ave. It was moving so fast they could not overtake it in the truck, according to the PD.

Naturally, they were unprepared to handle such a runaway blaze so the fire department was called. A single truck with 150 gallons of water was dispatched and quickly emptied. The fire was now out of control.

A second fire truck arrived, as did a crew and truck from the state as the fire line headed towards several farms. Students from the Junior College joined the fight and were credited with saving at least one home.

“Farmers, passing motorists, airport attendants and others fought side by side, beating out the flames with wet sacks and using portable water pumps in the two-hour battle,” the PD reported.

One farmer lost a small house and farm buildings, including a barn; another lost many outbuildings including chicken houses, where many animals died. Two orchards were burned over, power poles went up in flames and a large stack of baled hay continued to burn into the next day. Altogether 13 buildings were destroyed on five properties.

The idiocy of doing a controlled burn on an extremely dry and hot day aside, it’s jaw-dropping that it spread to 500 acres before a city and state fire crew plus a platoon of volunteers could control it – all in an area that was then undeveloped and just a couple of miles from town. What would they have done if the wind changed again and started blowing towards Santa Rosa?

Again, I hasten to add it’s probably just a Believe-It-Or-Not! coincidence that the big fires of 1908 and 1939 happened at the same places as 2017. Those fires don’t even have anything in common with each other; the airport fire was caused by a sudden change of wind and the Commandery burned like a torch amid no winds at all. One fire was avoidable, one probably not. What they do have in common is that both could have been catastrophic had the winds shifted towards Santa Rosa; the town could not have coped with a serious fire on its border at either time.

After presenting lots’o graphs and colorful maps, meteorologist Cliff Mass concludes with an optimistic view that our computer models are probably able to predict when conditions are ripe for a replay of the Tubbs Fire. That’s good news for sure, but the depressing message from history is that disasters aren’t always so foreseeable in reality. Sometimes life-threatening events comes from scientifically-predictable weather conditions, but sometimes the worst danger is just some fool dragging a burning rag behind a truck.

|

| Painting of the Commandery by Fountain Grove colonist Alice Parting as it appeared in the Pacific Rural Press, May 18, 1889 |

Top image of Commandery courtesy Gaye LeBaron Collection, Sonoma State University Special Collections

BIG RESIDENCE GUTTED BY FIRE AT FOUNTAINGROVEA Disastrous Blaze Near Town Wednesday NightThe explosion of the lamp resulted in a fire Wednesday night the destroyed the fine old residence at Fountaingrove, which for years occupied a commanding site on the hill overlooking the valley, greeting the eyes of every passerby along the Healdsburg Road. It was the biggest residence on the estate.

In a remarkedly short space of time, so fiercely did the fire fiend to do its work, the splendid building that rose four stories high, was reduced to smoldering embers. The residence was furnished and the contents cannot be saved. In addition a small creamery was also destroyed.

Shortly before 10 o’clock the fire started. The flames lit up the heavens for miles. People in Santa Rosa climbed into automobiles and carriages and left for the scene. At first many people thought the fire was at the old Pacific Methodist College building, and quite a number of them headed in that direction. Then it was said that it was Frank Steele’s residents near town. All these conjectures proved wrong.

The lamp exploded without warning and Mr. Cowie, who resided in the big house, was slightly burned about the face. The fire spread rapidly. The residence, built entirely of wood, was an easy prey. At the first cry of fire the large force of employees on the Fountaingrove estate rallied and did what they could to prevent the spread of the flames to other buildings. Numerous small hose were attached to faucets. Fortunately the north wind that had been blowing earlier in the day and evening died down, otherwise the flames would have spread. Some flying embers started a fire in the pasture but it was checked.

The house was well built. It had stood for about a quarter century. It was a largest residence on the place. When seen by a Press Democrat representative at the scene of the fire, Kanai [sic] Nagasawa stated that it would be hard to estimate the damage. Probably $35,000 to $40,000 will cover it. It is understood that there was some insurance on the place. Years ago, when the late Thomas Lake Harris published his books, the printing presses and other paraphernalia had aplace in the building destroyed. Of later years it had been used as a residence and for sometime prior to their going away from Fountaingrove Dr. and Mrs. Webley, and the Clarks occupied apartments in it.

There must have been a couple of hundred people in the crowd who drove out from Santa Rosa to the fire. Mr. Nagasawa took in the situation most philosophically, saying while it was too bad it had happened yet he was very thankful no one was hurt, and that there was no wind to scatter the fire further.

The old house will be missed. While it was the largest house it was not considered as fine as that occupied by the late Mr. Harris, which contains some valuable paintings, plate and furnishings. There are many Santa Rosans who have visited the Webleys and the Clarks there, and they will be sorry to learn of the destruction wrought by the fire.

For an hour or more after the fire, and while it was still in progress the telephone line to the Press Democrat office was certainly “busy.” The fire was seen for miles around and inquiries poured into the office.

Mr. and Mrs. Shirley Burris were leaving Healdsburg for Santa Rosa in their automobile at the time the fire started. Its reflection could plainly be seen there, and attracted considerable attention. All along the road people were out watching the flames.

While mention is made of those who went in automobiles and buggies to the fire those who rode horseback and on bikes must not be overlooked. There were many entries in these divisions. Several young ladies galloped on horseback to the scene of conflagration. For his speedy transit to Fountaingrove the Press Democrat representative was indebted to Frank Leppo, who drove his auto. When all the autos returned to town after the fire it made up quite a decent illuminated parade. An effort to reach Fountaingrove by telephone after the fire was met with the information the telephone had been destroyed with the building.

– Press Democrat, June 18 1908