Betty Carey rattled around the huge mansion the winter of 1922, alone except for the 20-member staff who served her. She was waiting for a court decision; at stake was whether she could be kept there indefinitely, against her will.

She was a prostitute and a drug user who hated being at the 40-room “castle” outside of Sonoma, but was ordered to be sent there by San Francisco Police Court Judge Lile Jacks. After a month she begged the judge to let her leave, writing she’d “rather serve a year in the county jail than spend a month in the Valley of the Moon.”

“What awful, narrow-minded people are in the beautiful Sonoma Valley!” she wrote, according to the SF Daily News. “They said I was so wicked they wouldn’t have me in the city of San Francisco, that I have actually asked one of the insignificant farmers for a cigarette. I did, Judge Jacks, such a breach of etiquette! Such small town newspaper talk! They said a woman captured me. It took three men to capture me…”

It was true her neighbors in the Sonoma Valley did not want her there, and their “small town newspaper,” the Sonoma Index-Tribune, objected fiercely. One reason was because the place was a point of local pride: The old Kate Johnson estate on the grounds of the historic Buena Vista winery, with 645 acres of vineyards and manicured lawns which were once compared to Golden Gate Park. The mansion was a landmark by itself, being probably the largest private residence ever built in Sonoma county and where it was gossiped that Mrs. Johnson had devoted an entire floor to her hundreds of cats. (Not true; see “THE MAKING OF A CRAZY CAT LADY.”)

But what the locals really disliked was not Betty’s presence. It was the fear that her pending court decision might mean five hundred more Bettys would be coming to live indefinitely at the big mansion in the Valley of the Moon. And all would presumably have venereal disease.

This is part one of our history of the “California Industrial Farm for Women” – usually instead called some variation of “the Sonoma State Home for Delinquent Women” – which explains the background about why the women were there; part two describes what happened after the Home opened and what became of the building.

It has been an uncomfortable article to write, which is probably why no local historians have touched this topic before. Understanding what happened/why requires wandering down some darker alleys of our past we’d like to forget; it requires coming to grips with how such unjust treatment of women was considered not only legal but embraced as fair and just – as were some unspeakable medical procedures which will make you cringe (or at least, should).

Also difficult to understand is how all this happened just as the women’s rights movement was at a historic peak, having just gained clout with the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920. Why wasn’t there backlash to the all-male legislatures and all-male courts declaring some women did not even have the basic constitutional right to bail or a trial? Surprise: The loudest voices chanting, “lock her up!” were other women – who believed people like Betty needed to be disenfranchised for their own protection.

This is a complex and grim story; although the Sonoma State Home for Delinquent Women was supposed to reform and benefit the women under its care, its real purpose was to protect men from venereal disease.

The estate where lonesome Betty Carey roamed was purchased by California in 1919 for a quarter million dollars 1920 for $50,000. Legislators didn’t seem to mind spending that much money for the grand old place, but from the start some were griping it could be put to better use than housing riff-raff like prostitutes and junkies, with a TB sanitarium or a home for disabled WWI veterans suggested as early alternatives. More on this thread in the following article.

That the state was spending such a large chunk of the budget on any sort of a female-only facility was considered a major victory for women. Starting more than forty years earlier, the W. C. T. U. and other temperance groups began beating the drums for a separate women’s state reformatory/prison; up to then female convicts from all over the state were crammed into small quarters at San Quentin. Some improvements were made after a shocking 1906 expose´ revealed there was no heat, rats ran loose and chamber pots were dumped into a hopper in the common room. But the women were still rarely allowed outdoors lest they be seen by the male prisoners, and windows in their quarters were whitewashed to likewise prevent men from peering in.1

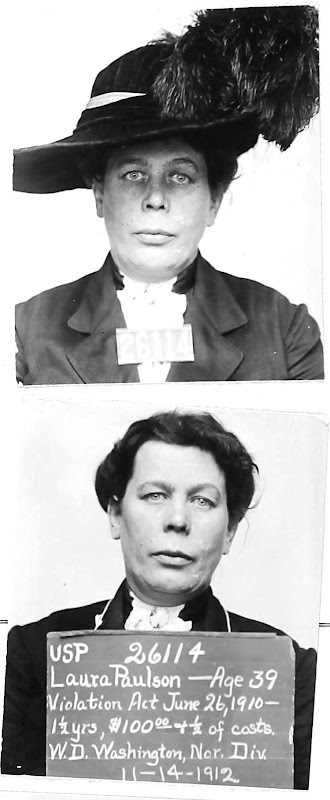

RIGHT: Few of the women at San Quentin in the early 1910s were guilty of sex crimes. One exception was Laura Paulson, wife of a saloon and dance hall owner in Burke, Idaho, convicted in 1911 under the “White-Slave Traffic Act” (the Mann Act) for bringing over prostitutes from Washington state

RIGHT: Few of the women at San Quentin in the early 1910s were guilty of sex crimes. One exception was Laura Paulson, wife of a saloon and dance hall owner in Burke, Idaho, convicted in 1911 under the “White-Slave Traffic Act” (the Mann Act) for bringing over prostitutes from Washington state

The awareness of how poorly women were treated behind bars came during a period of explosive growth in social groups for women (that same year, the Press Democrat gossip columnist estimated there were 100 women’s clubs in Santa Rosa, when the town had a population of about 10,000). After California women won suffrage in 1911 the clubwomen became a formidable political bloc, and before the end of the decade the Women’s Legislative Council of California claimed it represented over 187,000 club members throughout the state. Improving conditions for “delinquent women” was among the Council’s top priorities – but what did that mean, exactly?

At the 1918 Council convention they urged the state to “establish rehabilitation farms and colonies for delinquent women and to establish a state boarding school for incorrigible public school children whose offenses do not demand reformatory treatment.” Take note first of “farms and colonies;” it was long presupposed by prison reformers and women advocates that rural, women-run institutions would transform law-breaking ladies into model citizens. “These pastoral prisons were supposed to accommodate the domesticity attributed to women’s natures,” explained prison historian Shelley Bookspan, because they could have “schooling and training in marketable female skills, such as sewing, mothering and nursing.”2

Second point: Even though the term was widely used, “delinquent woman” had no clear definition. Did it mean a sex worker/drug addict? A woman charged with any crime? Here the Council lumps delinquent woman together with juvenile delinquents (“incorrigible public school children”) which implies a D. W. is someone who makes poor decisions and may have committed petty crimes. The latter was indeed the definition earlier in the 1910s when legislators first considered a women’s farm; in a 1911 article transcribed below it’s stated that a delinquent woman was someone who had committed five or more misdemeanors such as drunkenness, vagrancy or shoplifting.

The clubwomen clearly expected a woman’s farm would be used for women who could be rehabilitated and released, but less clear is whether it was believed the place would be used to house all female criminals. Even as the opening date approached, there was uncertainty about who would be sent to Sonoma. Recently released from San Quentin was Dr. Marie Equi, who had served time for sedition.3 Shortly before Betty Carey became the test case, an Oakland Tribune reporter interviewed Dr. Equi, who apparently believed all the women inmates at San Quentin were going to the elysian gardens at Buena Vista:

| The girls at Quentin are wild to get on the farm. They are housed in a little square mausoleum being permitted to go out among the green fields but once a week and having nothing to do to occupy their minds…The women inmates at San Quentin are not morons by any means…my cell mates at San Quentin were just the type of bright, pretty ‘chickens’ that the tired business man cultivates for his amusement. Check-passer, murderers, women of the street, forgers and narcotic addicts mingle together… |

But although the April, 1919 act establishing the Home stated it was “to provide custody, care, protection, industrial, and other training and rehabilitation for the delinquent women,” none of that would be provided, except for custody and care. And few, if any, of Dr. Equi’s cellmates would be welcome. The Home was only for women like Betty Carey – prostitutes who were to be held under an indefinite quarantine because they had diseases considered nearly incurable at the time.

The Home never would have existed if not for the Wilson Administration’s obsession with the so-called “American Plan,” starting when the U.S. entered World War I and continuing on through most of the 1920s. Like Prohibition which soon followed, this was a morals crusade in the guise of patriotism – in this case, keeping our boys healthy before they went overseas to fight the Germans by attempting to eradicate venereal diseases.

There had been vice crackdowns in American cities before, or course, but the War Department decided the U.S. needed “invisible armor” around every training camp to protect soldiers against “heated temptations.” A five-mile radius “moral zone” was established around the camps where no alcohol could be sold; women suspected of being prostitutes could be detained and forced to undergo a blood test and gynecological medical exam. Even though any sexually active woman could have a venereal disease, every woman found to have VD was presumed to be a prostitute – and every prostitute was presumed to have VD. And that meant she could be locked up without due process.4

Besides local and military police, the Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA) created its own national Law Enforcement Division and even local public health investigators now had powers to arrest civilian women on suspicion. The dragnet expanded after Congress passed The Chamberlain-Kahn Act of 1918, which was not restricted to the immediate vicinity of military camps. It’s usually said 30,000 women were swept up, but Scott Wasserman Stern, the author of an excellent study on the American Plan (see footnote 4), believes that greatly underestimates the true numbers.

The need to lock up so many women created a problem of what to do with them all. Local hospitals and jails were kept full; state reformatories and orphanages were pressed into service and the CTCA began building detention camps. In a believe-it-or-not! twist, the feds decided that former brothels were ideal places to house them – just surround the place with barbed wire and add guards.5

Much of this was being paid for with money personally controlled by President Wilson, including $1 million from the Chamberlain-Kahn Act. And it wasn’t just for lockup; the CTCA was also charged with lobbying states to adopt a set of model laws it had written to curb promiscuity. Among the provisions were creating reformatories for women detained on “incorrigibility or delinquency” charges and outlawing all premarital sex. By 1919, 39 states had passed such laws.

To be sure, VD was endemic among prostitutes. A 1917 San Francisco study found 72 percent had syphilis, gonorrhea or both. In that year – just as the CTCA was starting – the city was lenient, allowing women who tested positive to sign an agreement to report to a physician or clinic within a few days. If she was not known to have a disease, a woman paid a $5.00 bail and was released, even though some were rearrested up to four times a night and certainly not retested every time. Under new pressure from federal officials, the bail was increased to $1,000 for the first arrest. As a result of the astronomical increase, many skipped bail and fled the city for places with lax enforcement.

To be sure, VD was endemic among prostitutes. A 1917 San Francisco study found 72 percent had syphilis, gonorrhea or both. In that year – just as the CTCA was starting – the city was lenient, allowing women who tested positive to sign an agreement to report to a physician or clinic within a few days. If she was not known to have a disease, a woman paid a $5.00 bail and was released, even though some were rearrested up to four times a night and certainly not retested every time. Under new pressure from federal officials, the bail was increased to $1,000 for the first arrest. As a result of the astronomical increase, many skipped bail and fled the city for places with lax enforcement.

Today it may seem odd that infected women did not eagerly agree to medical treatment, but in that pre-antibiotic era the options ranged from bad to awful; there was no guarantee of being cured – but weeks, months, or a lifetime of pain was assured and side effects could be crippling or lethal.

Arsenic-based Salvarsan was the first drug that could actually cure syphilis but problems abounded with the treatment: The shot was described as “horribly painful” followed by days of sustained misery – and the drug would be effective only if it were prepared immediately before injection under precise, nearly laboratory, conditions. Repeat for 4-8 weeks.

At the time the wonder drug for gonorrhea was 3-6 weeks of shots with a solution where the main ingredient was mercurochrome. Like the syphilis treatment, though, the compound had to be absolutely fresh and precisely formulated to cure. For women with untreated chronic gonorrhea – which most prostitutes suffered – doctors cut away or cauterized any parts of the reproductive system they deemed infected. Surgical procedures were routinely performed that today would be condemned as types of female genital mutilation.6

But let’s presume our misfortunate heroine, Betty Carey, was given the full course of treatment and it worked exactly as hoped. She’s now completely STD free. Maybe she sticks around the Buena Vista castle a little longer for followup tests to show that she’s really and truly cured; maybe she’s required to attend a class on contraception and safe sex taught by someone from Margaret Sanger’s new American Birth Control League. But after that, she would be given a pile of condoms and released, right?

Sorry, Betty – that might be the European Plan, but it wasn’t the American Plan. Over there prostitutes had to be registered so their health could be monitored for public safety; over there use of condoms was encouraged. Here prostitution was being driven underground by the new, harsher CTCA-written laws; here we didn’t even send our boys overseas in WWI with condoms, despite all the Wilson administration’s squawking about soldiers “keeping fit” and the president personally directing spending on ways to protect them from VD.

No, the state was not yet done with Betty; besides confinement and care, section one of the delinquent women act also calls for rehabilitation. What did that legally mean? How could Betty prove to a judge and the Board of Trustees that she was rehabilitated – and from what, exactly? Remember: She had not been convicted of prostitution or any other crime, but instead simply ordered to be sent to the Home by a justice of the peace.

Her court-appointed attorney immediately appealed when she was sentenced to the Home. For three months Betty would pace the empty corridors of the mansion awaiting a decision from the state appeals court. If she lost, they could keep her there up to five years.

Betty Carey’s fate was to be decided by the 3rd District Court of Appeal in Sacramento. As Gentle Reader already knows there’s more to appear here about the Home for Delinquent Women, it’s not much of a spoiler to reveal now that she lost her case. Badly. But it’s the court’s reasoning behind the decision that is a true jaw-dropper, and reveals how unjust and unconstitutional the overall concept was.

Had she won any of her points it would have been unprecedented. The first suits against such sentencing appeared not long after the launch of the American Plan; with CTCA encouragement, Seattle police had conducted widespread vice raids, sweeping up “suspicious” and “disorderly” women and men (including labor activists) during the winter of 1917, holding them without bail or court hearings and forcibly starting the painful treatments whether the person had VD or not. Judges dismissed the complaints, ruling the police were acting in the interest of public welfare.7

One of those cases made it to the Washington State Supreme Court in 1918 and set an astonishing precedent. An unelected official – in this case, Seattle health commissioner J. S. McBride – had virtually unlimited authority to declare someone had a contagious disease and thus hold the person indefinitely in quarantine. Dr. McBride even refused to allow those being held to communicate with their attorneys. Not only was venereal disease now in the same category as lethal communicable diseases such as smallpox or plague, it gave police the authority to arrest and deny rights of habeas corpus to anyone they claimed was “reasonably suspected” of having VD.8

It cannot be said Betty had a poor defense. The petition for appeal was brought by Darwin J. Smith, then a statehouse reporter for the Sacramento Bee, and the attorney arguing on her behalf was Charles E. McLaughlin, Director of the State Prison Board and a former judge on the same appeals court. Their defense had five basic points:

|

A police court doesn’t have the power to commit offenders to reformatories |

|

A police court can’t commit someone to an indefinite sentence |

|

Commitment to an indefinite sentence is cruel and unusual punishment |

|

It is discriminatory to confine women to reformatories for sex crimes and not men |

|

It is discriminatory to confine women for soliciting sex yet not men for pimping, which is soliciting sex on behalf of a woman |

All were strong arguments, and in another context or another time, at least some should have won the day. But the appeals court turned down everything, even though they had to frequently wander out into legal weeds. You can read the entire decision in a few minutes; it’s only five pages. But you might want to first make sure the windows are tightly shut because you’ll probably be screaming in outrage.

Let’s get the most absurd stuff out of the way first: The court claimed the law couldn’t lock up men in the way they were about to incarcerate Betty. Why? Because there was no such thing as a male prostitute (“men cannot commit the crime of carrying on the business of prostitution…a business that can be carried on only by women”).

Next: Betty’s indefinite sentence couldn’t be considered cruel and unusual – because it wasn’t actually indefinite. Today we’d call it a Catch-22 situation: “It has uniformly been held that the indeterminate sentence is in legal effect a sentence for the maximum term.”

Women had no more legal rights than children. In order to justify Betty’s commitment to the Home by a police court judge, the appeals court cited two decisions, one of its own and another from the state supreme court. Both concerned juvenile offenders being sent to reformatories. Part of the supreme court cite stated the police court was just acting in the same role “…which, under other conditions, is habitually imposed by parents, guardians of the person, and others exercising supervision and control…”

The court also used the comparison to juvenile delinquents to make the Orwellian claim that Betty wasn’t being incarcerated at all, but merely being required to attend a reform school. Again quoting the state supreme court regarding police courts sending children to reformatories: “…the purpose in view is not punishment for the offense done, but reformation and training of the child to habits of industry, with a view to his future usefulness when he shall have been reclaimed to society…”

The longest, and most important part of the appellate court decision, didn’t address any of Betty’s complaints; instead, it attempted to justify the need to quarantine and disenfranchise women like her. Prostitutes, the judges wrote, are a unique danger to the rest of “the human kind.” They are like “the chronic typhoid carrier – a sort of clearing house for the very worst forms of disease” and that they are “a constant pathological danger no one would question.”

| …The statute in question does not purport to deal with her as an innocent person. On the contrary, the law appraises her as so steeped in crime and in so exceptional an environment that ordinary methods of reformation and escape are impossible. Every door is closed to her. Every avenue of escape is shut off. The state, realizing this, has undertaken to take forcible charge of this class of unfortunates and extend to them a home, education, assistance, and encouragement in an effort, otherwise hopeless, to restore them to lives of usefulness. |

This mix of loathing and compassion matched the clubwomen view, and they likewise shared a belief that Betty and the others had to be locked up until they were rehabilitated. Given enough time, eventually they would have to emerge from their chrysalis as women of adequate moral character – just as Prohibition would surely transform every drunk into a fine sober citizen.

With the court decision lost, Betty was no longer alone at The Sonoma State Home for Delinquent Women, as the “castle” began to fill up with women inmates from San Quentin and other prostitutes sentenced directly from police courts.

As for the “education, assistance, and encouragement” the court promised she would receive, Betty told the San Francisco Daily News she was being treated like an imbecile or a naughty child, with nothing to do except caring for farm animals. “I feel like one of the goats out on this farm,” said the woman born in New York City, “I shall never milk these goats.”

| 1 A Germ of Goodness: The California State Prison System, 1851-1944 by Shelley Bookspan, University of Nebraska Press, 1991; pg. 74-75 |

| 2 ibid pg. 77-78 |

| 3 Under the Sedition Act of 1918, criticism of the U.S. government, the American flag or military uniforms was outlawed. As a socialist and outspoken pacifist while the country was gearing up to enter WWI, Dr. Marie Equi was an early target of J. Edgar Hoover, then a rising star at the Bureau of Investigation office charged with harassing “radicals.” |

| 4 The Long American Plan: The US Government’s Campaign Against Venereal Disease and Its Carriers by Scott Wasserman Stern; Harvard Journal of Law & Gender, 2015 (PDF). Much of this section is sourced from this excellent thesis. |

| 5 ibid, pg. 384 |

| 6 Mercurochrome was not universally accepted as a cure for gonorrhea, and the medical journals c. 1920 show physicians experimenting with a wide variety of treatments which were frequently torturous. Because it was known that a sustained high fever killed the bacteria, electrical rods or cathode ray tubes (gauss lamps) heated to 112 F were sometimes inserted vaginally for up to four hours a session and repeated daily. The most common form of gonorrheal surgery was removal of the Bartholin glands, which would cause the women agonizing pain during sex for the rest of their lives. And if that wasn’t punishment enough, the gynecology department head at the San Francisco Polyclinic Hospital wrote in the 1922 AMA journal that the Skene’s gland also should be cauterized with a hot needle, which would have destroyed nerve endings (PDF). |

| 7 op. cit. The Long American Plan, pg. 389 |

| 8 ibid, pg. 393 |

|

| Collage of San Quentin mugshots, 1918-1919 |

ALL FARMS LOOK ALIKE TO WALLACEAgricultural Committee Will Grapple With Delinquent Women BillAim of Measure Is to Take Female Prisoners From Penitentiaries[Special Dispatch to The Call]

CALL HEADQURTERS SACRAMENTO, Jan. 13.—Thanks to Lieutenant Governor Wallace’s determination to accept things for what they may appear to be, a bill designed to establish an indeterminate sentence farm for delinquent women who have been convicted of five or more misdemeanors reposes in the hopper of the senate committee on agricultural and dairy interests.The bill, which Is a free copy of the New York law for the treatment of delinquent females, has the support of virtually all the women’s clubs of California. It provides for the appointment by the governor of a board consisting of the prison directors and two women to have the management of a state farm for the custody of delinquent females. The board is to select a site and upon approval by the governor purchase it and equip it with buildings for the accommodation of at least 250 inmates. The farm is to take the place of custody for females over the age of 25 who shall have been convicted on misdemeanor charges five times. The sentences are for indefinite terms, but not to exceed 3 years.

The women’s organizations framed the measure and gave it to Finn, chairman of the committee on prisons and reformatory, for introduction. Finn sent it to the desk confidently expecting that Lieutenant Governor Wallace would immediately refer it to his committee. The reading of the title “state farm for the custody of delinquent females” was lost on none but Wallace. He gravely referred the measure to the committee on agricultural and dairy interests, A shout of laughter instantly went up, but it failed to perturb Wallace. A farm measure the bill was labeled and to Wallace farm suggested agricultural and dairying.

– San Francisco Call, January 14 1911

WOMEN PRISONERS WILD TO GET TO BUENA VISTA.Recently Released Political Prisoner From San Quentin Says Newcomers to Delinquent Women’s Farm Here Will Be “Classy” JanesThere has been considerable specilation among Sonoma Valley folks as to the kind of wards the State of California is to care for at the new penal institution at Buena Vista. The former Kate Johnson place known as the Castle was purchased about a year ago to be used as a farm for Delinquent Women and according to Dr. Marie D. Equi, recently released political prisoner from San Quentin, the women are yearning to get here and will be bright, classy Janes. Here is what the Oakland Tribune reveals:

“Girl prisoners at San Quentin penitentiary are the smartest women felons in the United States, according to Dr. Marie D. Equi, political prisoner, who has just been released from the prison and who says that the latest styles are all the vogue at the Marin county resort.

“The women inmates at San Quentin are not morons by any means,” Dr. Equi declared yesterday. “They roll ‘em down, wear ‘em high and the sleek silk-clad ankle and high-heeled shoe are always in evidence at the parties staged in S. Q. F. D.” The S. Q. F. D. means the San Quentin Female Department, she explained.

The high moral tone at the State prison, however, bars cigarettes for the girls, limits the night owls to 10 p.m., prohibits debutantes from going out unchaperoned, while at the same time countenancing the “shimmy,” the bunny hug” and the “San Rafael Waddle,” Dr. Equi says.

CLASSY PRISONERS

“Western women prisoners are greatly superior in all respects to the inmates of Eastern penitentiaries where the majority in the female departments are morons or lower,” Dr. Equi, a graduate physician of Portland continued.

My cell mates at San Quentin were just the type of bright, pretty “chickens” that the tired business man cultivates for his amusement. Check-passer, murderers, women of the street, forgers and narcotic addicts mingle together – crochet, sew, cook, read books, discuss the latest styles or dance in the big living room to the jazz tunes of a piano, just like their sisters outside.

“These girls are intelligent, not intellectual. Some of them are more intelligent than the intellectual free women. Their wits are sharpened from contact with the world.”

STATE FARM BOOSTED

Dr. Equi is beginning a campaign to have the women prisoners at San Quentin transferred immediately to the new farm provided for them near Sonoma.

“Here the women will live an outdoor life and will be able to work and become more self-supporting,” says the Doctor. “The girls at Quentin are wild to get on the farm. They are housed in a little square mausoleum being permitted to go out among the green fields but once a week and having nothing to do to occupy their minds.

“Their removal from the prison to the farm is being held up pending the construction of a hospital. I contend that the women can be transferred and the hospital built afterward…

– Sonoma Index-Tribune, September 3, 1921WILL TEST SONOMA FARM LAWSan Francisco, December 7.- Following the sentencing of Betty Carey, an alleged drug addict, to the new state home for delinquent women, near Sonoma, for an indefinite term, legal steps will be taken to test the law giving the courts authority to impose such sentences.

This was decided upon today by Police Judge Lile T. Jacks when he announced that he would pronounce sentence sending Betty Carey to the home.

Attorney Harry McKenzie, appointed by the court under agreement with Chief of Detectives Duncan Matheson, to appeal from the court’s judgment in the case, in order to test the law, expressed the hope that the law would be sustained.

Judge Jacks and Captain Matheson also declared their hope that the law would be upheld and thus give the courts clear headway in their efforts to cure the addicts who are brought before them.

The question at issue is whether or not the courts have the right to deprive an addict of his or her liberty for an indefinite period.

– Sotoyome Scimitar, December 9 1921

First Woman for Sonoma FarmMiss Betty Carey, who lost a Christmas present of her liberty by failing to leave town as she promised Police Judge Lile T. Jacks, was Saturday ordered committed to the Sonoma Home for Girls. She is the first woman to be sent to the new home on court order from San Francisco county.

– Argus-Courier, January 9, 1922WOMEN MAY BE SENT TO FARMCourt of Appeals Upholds Act; Will Operate to Protect Morality(By Associated Press leased Wire)SACRAMENTO, April 10. The constitutionality of the act establishing the state prison farm for women and also the right of police and justice courts to sentence women to the prison farm for a period not exceeding five years, today were upheld by, the third district court of appeals, denying the application of Betty Carey, an inmate of the farm, for a writ of habeas corpus.

Four points were urged by Judge C. E. McLaughlin on behalf of the petitioner in applying for the writ, as follows:

That it was beyond the jurisdiction of the police court of San Francisco where Betty Carey was arrested to sentence her to the prison farm for an indeterminate sentence which might amount to a detention for five years; that the punishment is cruel and unusual; that the act is discriminatory in that it applied only to women and that the legislation can not be general enactment modify an ordinance of San Francisco.

Replying to Judge McLaughlin’s first contention, Judge J. T. Prewett of Auburn, as the juristice protem, who wrote the opinion, declared the claim that the police court was without jurisdiction to sentence women to the prison farm was untenable. He cited Supreme Court cases upholding the right of police and justice courts to commit minors to reformatories and he held the same right existed in the matter of sentencing women to the prison farm. He declared the purpose in view is not punishment for the offense done but reformation to reclaim the women to society.

Being that the commitment of women to the prison farm is only for the purposes of assistance and reformation,” Judge Prewett held that the incarceration can not be regarded as cruel and unusual punishment.

Replying to Judge McLaughlin’s claim that the statute is unconstitutional in that it discriminates against women, Judge Prewett quoted from a Supreme Court decision holding that legislation may be directed to women as a class and that they may be segregated into groups or sub-classed in the interests of public health, safety or morals.

– San Bernardino Sun, April 11 1922