There was no question who killed the Wickershams because no one questioned who killed them; it was definitely their Chinese cook – right?

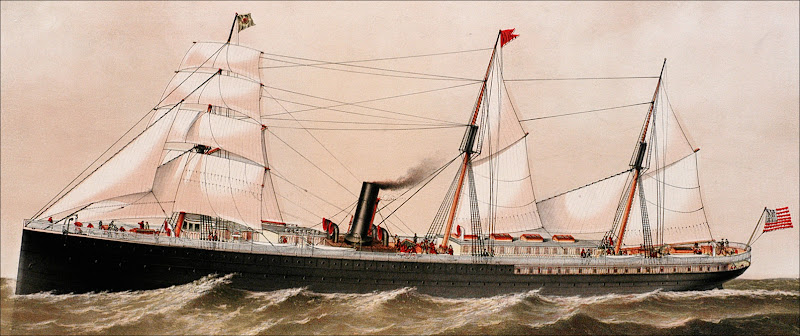

This is the final chapter in the series about the 1886 killings of Sarah and Jesse Wickersham on their ranch at the most remote part of Sonoma county, between Cloverdale and the ocean. The same night, their cook – whose real name is unknown and here called “Ang” – ran away to San Francisco where it was presumed he boarded a steamship bound for China. This man was apprehended once the boat landed and he died in a Hong Kong jail cell – supposedly by suicide rather than face extradition to California. Further details can be found in the chapters listed to the right.

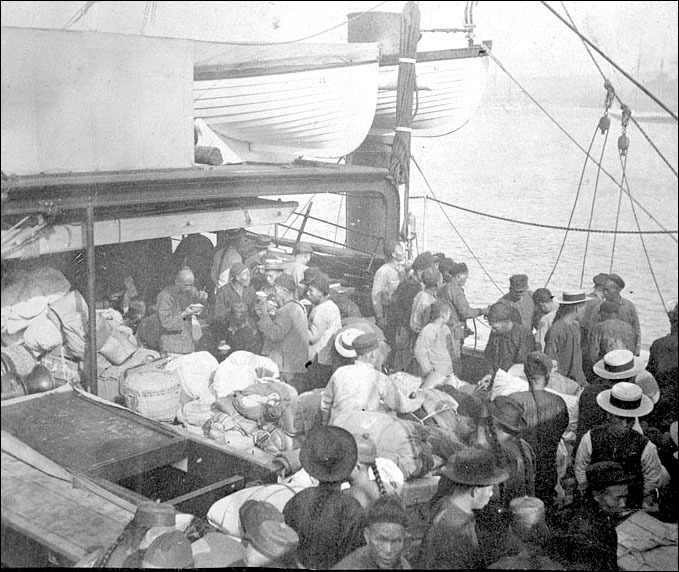

News that one of their countrymen had murdered Americans spread fast and far, and could have hardly come at a worse time for Chinese immigrants in the West. For months, anti-Chinese sentiments had been escalating from grumbling newspaper editorials to acts of violence, even mob riots. Eureka banished its 300+ Chinese residents, as did Tacoma, which followed by razing its Chinatown area. In Wyoming, white miners went on a rampage and murdered at least 28 Chinese men with many burned alive.

Ang was a perfect villain in that swirling torrent of racist hate and fear. The story being told was he had murdered the couple in cold blood for no apparent reason, shooting Jesse Wickersham in the back of his head while he was eating supper and tying Sarah to her bed before killing her as well (some versions of the story also falsely suggested she was sexually assaulted). As a domestic servant living under the same roof as them, the Chinese haters pointed to it as proof that none of the immigrants could ever be trusted, that they could unexpectedly turn on you like a rabid dog. And that fever burned no hotter than in parts of Sonoma county, where the Wickersham victims were members of an esteemed Petaluma family.

Trouble was, Ang made for a lousy suspect. There was zero evidence linking him to the double murder. He had no known motive nor history of trouble; a journal found in his room was translated and revealed a bent towards philosophy. Louis Smith, who worked frequently for the Wickershams and seems to have known Ang better than anyone else, told a reporter that Ang was a “good Chinaman” and “…got along nicely at the ranch and said he liked the place. When last asked how he was getting on he said all right, but he did not know how long he would remain…”1

But if it wasn’t Ang, then whodunnit? I believe the culprit was apparent at the time, but swiftly overlooked because the focus entirely turned to the exciting pursuit of (the man believed to be) Ang enroute to Asia. Further, I believe reenacting the event based on the inquest and descriptions of the crime scene supports no other possible interpretation. Read on.

The first suspect to consider has to be Elliott Jewell, the neighbor who discovered the murders. Jewell said from the beginning he believed the Chinese cook killed them – in fact, he wouldn’t shut up about it. As an honors graduate of ACU/Wingback (Agatha Christie University, Armchair campus), I can tell you that the character who kept yapping “the butler did it, the butler did it” likely was the one who killed Colonel Mustard in the library with the candlestick.

Jewell told the Coroner’s Jury he was certain Ang was the killer, although he had no proof to offer: “I think China cook killed him; [I] should think so from the position of Mr. Wickersham and disappearance of Chinaman.” As for Mrs. Wickersham, Jewell testified, “I do not know who killed her but believe it to be [the] Chinaman.” Based on that (non) evidence, the Jury decided “ail evidence [was] pointing towards a Chinese cook in the employ of deceased.”2

Around two miles away, Jewell and his wife were the closest neighbors. “We were continually over at each other’s places,” he later said, and the four of them had just spent the long New Years’ weekend together. The Jewell’s ranch was something of a country retreat for the couple as both he and his wife were prominent in Petaluma society; he also owned an important business there and had investments.3

Like Ang, however, Jewell had no apparent motive to kill the Wickershams. While we can’t rule out a crime of passion, shooting them separately and tying up Mrs. Wickersham doesn’t seem like part of an impulsive act.

Still, this detail bothers: Jewell did not say anything about hearing the three (four?) shotgun blasts that evening. Even at two miles they should have been noticeable – and that two miles was by road, so the houses might have been closer by earshot. Remember that was 1886 and there was no TV, radio, motors humming or other distracting sounds, just mountain stillness a few hours after sundown on a winter’s night.

But in the brief window before Jewell and the others put the spotlight on Ang, another sort of suspect was considered. In the very first article in the Santa Rosa newspapers about the killings, the Democrat wrote, “…The general supposition is that the crime was committed by parties who expected to obtain possession of his money, knowing that he had many men in his employ, and being such a distance from town they probably thought he kept a large sum of money in his house…”4

That’s the simplest – and I argue, most likely – explanation of the murders: It was a robbery gone wrong. A criminal learned a middle-aged recluse had a sheep ranch in a very remote area. The man was weak or sickly and couldn’t do much so he relied upon hired hands, which meant he must have cash money around to pay them. The man was a Wickersham, and everybody knew they were the North Bay’s wealthiest banking family. The man was married, and rich wives must have valuable jewelry.

As this history blog is concerned with Santa Rosa and the surrounding county, little has been mentioned here about what was going on outside our little bubble. But in 1886 a traveler heading further north would have found it steadily became wilder and woolier, and from Cloverdale onward it well could be considered frontier.

Today writers romanticize highwaymen like “Black Bart,” the gentlemanly robber who left some poems. Forgotten are his vicious colleagues such as Buck English and his gang, who terrorized Napa and Lake counties with brazen stickups at gunpoint. Buck supposedly wasn’t in the area at the time (I can’t find conclusive proof of that) but there were plenty of other bad guys around.

On January 28, a week after the Wickersham murders were discovered, the front page of the Los Angeles Herald neatly summarized the trends going on that week in Northern California. Item 1) reported the arrest of a man in Cloverdale who attempted to rob a stagecoach; 2) provided the latest details on the Wickersham case from Santa Rosa; and 3) mentioned a secret meeting held in Red Bluff to drive out their Chinese residents.

On January 28, a week after the Wickersham murders were discovered, the front page of the Los Angeles Herald neatly summarized the trends going on that week in Northern California. Item 1) reported the arrest of a man in Cloverdale who attempted to rob a stagecoach; 2) provided the latest details on the Wickersham case from Santa Rosa; and 3) mentioned a secret meeting held in Red Bluff to drive out their Chinese residents.

That thwarted stage holdup was not unusual; in 1886 there was a rash of other armed robberies in the region. About three weeks after the Wickershams were killed a couple of masked men robbed a convey of pack horses carrying mail outside of Cloverdale. The same month two armed robbers held up horse buyers on the road to Alexander Valley. There were at least three other highway robberies later that year around Cloverdale, according to the Santa Rosa newspapers.5

Sometimes the holdup guys were later caught (gotta admire those Wells Fargo detectives) or made jailhouse confessions, but none were implicated in the Wickersham deaths. And that may be the strongest evidence that highwaymen were not the real killers. Those dimwits seemed to squeal on each other eagerly, and there was an enormous $1,500 reward offered in the Wickersham case – although it’s not clear whether or not it was specifically for the capture of Ang.6

I readily concede there is a real chance that everything happened as they presumed at the time, that Ang the Chinese cook went berserk for some unknown reason and murdered the couple. But once you strip away the racist notions about the Chinese being monsters, that interpretation makes little sense. Evidence shows it is far more likely that two (or more) robbers surprised them in their home, demanded money and murdered them not to leave witnesses. In this scenario, Ang is completely innocent but flees because he thinks they are pursuing him, or he anticipated (correctly) he would be presumed guilty.

Deciphering whatever really happened mostly comes down to answering this question: Who placed the napkins?

Four days after the killings, a party of 17+ men crowded into Wickersham’s small cabin to investigate and hold an inquest. From there emerged six first-hand accounts of mixed quality.

All of the damning claims – that Sarah Wickersham had been “outraged,” that a piece of cake was left next to her as some sort of Chinese offering to the dead, that she feared to be alone with Ang and that he supposedly killed someone in Sacramento – can be traced directly to Petaluma City Marshal Julius Blume and Healdsburg Constable Roland Truitt, both of whom were quoted widely in the press. Any article relying entirely upon these highly prejudicial lawmen has to be dismissed as untrustworthy.

Fred Wickersham, the adult cousin of Jesse, confirmed some important details in a telegram to his family and later knocked down some of the stories being told by Blume and Truitt. As mentioned already, neighbor Elliott Jewell had little to offer aside from parroting “the Chinaman did it.”

The most reliable sources were a description of the scene by a correspondent from the Petaluma Courier (no byline) and details found in the Coroner’s report about the bodies, per testimony by the doctor who performed the autopsies. (Unfortunately, the inquest did not include any testimony concerning material evidence.) Based on those two accounts, here is the information we can trust:7

All signs pointed to the Wickershams being interrupted while eating supper. Food was still on their plates at the table and the lamp on the table had burned out of oil. Jesse was seated with his back to the fireplace, the door next to it leading to the kitchen. He looked as though he had fallen asleep in his chair. The autopsy found he had been shot twice, once in the back of his head with the other shotgun wound on his side.

|

Scene of the Wickersham murders showing the approximate position of the victims. In the actual crime scene Sarah was seated directly across the table from Jesse but is shown here at the side as to not obscure him from view. The people shown were selected from vintage images on the internet and are NOT either of the Wickershams. An untouched view of the room can be found in part one. Photo courtesy David Otero and Wickersham Ranch

|

Sarah was found in their bedroom (presumably the door on the left in the photograph). She was thoroughly tied up with clothesline, her arms pinned behind her back and the end of the rope tied to the head of the bed. She was in a kneeling position with her head resting on the mattress and was killed by a single shotgun blast to her side, likely standing but already tied up.

Most viewing the scene remarked on the evidence on the kitchen door. The Courier: “On the kitchen side, about four feet from the floor, were marks of powder burn almost as large as a man’s hand. The gun from which the shot was fired that ended the life of the owner of the house was evidently held close against the door, and in that position the muzzle would have been only about five feet from the body of the unsuspecting victim.”8

The shotgun was found in its usual position in the kitchen, leaning behind the door. “On the table was two empty shells, and two other empty shells were taken from the gun.” As there were three shotgun blasts in the killings, it is unknown if the fourth used shell was already in the gun. There is a large bullethole in the ceiling in front of the bedroom door but it’s unknown if that was made by the killers or was the work of some joker at a later time. No contemporary source mentioned it.

After mulling over the evidence for the better part of a year, here’s my best guess as to what happened:

Around six in the evening on Monday, January 18, two or more men rode to the Wickersham ranch. Someone had been there before (one of Jesse’s many hired hands, perhaps?) and knew how to find the place; it was off a lane which was then little more than a cowpath and far from main roads.

As they approached the ranch a heavy storm was brewing, if rains were not already lashing the hills. The flooding resulting from that and a following storm would hamper investigators later in the week, but on the night of the murders the bad weather only added to the enveloping darkness. There was no electricity at the cabin in 1886; the only light inside was the weak glow from candles and coal oil lamps, with the robbers certain to have carried in hurricane lanterns which would cast deep shadows as they moved around.

The small cabin has three rooms and a kitchen; there is a front door in the room where the Wickershams were eating. In the kitchen there is a back and a side door which the robbers probably used, likely carrying revolvers or long guns. At the time everyone presumed the Wickershams were killed by Jesse’s own shotgun, but no evidence of that was ever given – we’ll just have to take their word because back then, they certainly knew a thing or three about firearms.

The small cabin has three rooms and a kitchen; there is a front door in the room where the Wickershams were eating. In the kitchen there is a back and a side door which the robbers probably used, likely carrying revolvers or long guns. At the time everyone presumed the Wickershams were killed by Jesse’s own shotgun, but no evidence of that was ever given – we’ll just have to take their word because back then, they certainly knew a thing or three about firearms.

The assault probably began with a shotgun blast fired from the kitchen into the front room. I believe this caused the hole in the ceiling, and was intended to surprise and terrify the Wickershams.

I imagine the frightened couple must have jumped to their feet, throwing their hands in the air – whether ordered or not. The accomplice(s) likely made a quick search of the cabin, finding the coil of clothesline rope in Ang’s room which they used to tie up Sarah, all the more to terrorize Jesse into revealing the whereabouts of his supposed strongbox.

Jesse likely protested there was little gold coin in the house – he usually paid everyone by a check from a Healdsburg or Petaluma bank account. This was borne out by others who later spoke to reporters, including neighbor Jewell, in one of the few moments when he wasn’t yammering about the Chinese cook being the killer: “He could hardly have been murdered for the sake of any money that he might have about the house, because in all our transactions I used to be given a check on the bank, Wickersham often telling me that he had strong objections to keeping money in the house”. (True to form, Jewell followed that statement by volunteering, “the only solution that I can give you of the mystery is that the Wickershams have been murdered by the Chinaman.”)9

Here’s the most controversial part of my interpretation: I don’t believe the robbers went there intending to murder anyone, and I think the shot that killed Jesse was accidental. The highwaymen mentioned above rarely fired their guns except to scare people.10

It appears everyone presumed Jesse was first shot in the head – but I believe the autopsy evidence proves not; the doctor said only that either shot would have killed him. He was meticulous in describing the buckshot in Jesse’s body, and no wound was mentioned in his right arm. This suggests his hands were up when he was shot in the side and fired by someone slightly behind him. Like the blast from the doorway, the upward trajectory of the buckshot found in the autopsy suggests the gunman was firing the weapon from his hip, most likely holding a lantern in his left hand with his right trigger finger on an unfamiliar shotgun. It’s easy to imagine how it could happen.

The bandit was not facing Jesse and probably still in the kitchen doorway, which is why the blast hit him “a little posterior to middle” between his fifth and sixth ribs (directly below the sternum), as the coroner wrote. He fell back into his chair, slowly bleeding out with buckshot through both lungs and heart. But the worst was yet to come.

Those pushing an anti-Chinese agenda made up details about the scene where Sarah was discovered bound by the rope, but all described her having been savagely beaten on her head and face, most likely as the robbers demanded she reveal where all the money was hidden. Her “…face was swollen and bruised, the appearance ghastly in the extreme,” reported the Petaluma Courier, and another account stated her nose was broken. A witness who saw her body at the undertaker’s said her “face was much discolored.” There were further nightmarish descriptions which I am sparing Gentle Reader.11

The robbers left, but not before a point blank kill shot to the base of Jesse’s brain – the amount of bleeding makes it apparent the first shot had not killed him. His “pool of blood” was mentioned more than any other detail, the Petaluma Courier noting specifically, “beneath the chair on which the body rested were two pools of blood…”

Besides the made-up stuff about Sarah’s sexual assault and the ritual offering of cake, the other big canard was that nothing was stolen, thus proving it was an act of rage by a deranged Chinaman. But no one knew how much money Jesse had around to steal, if any. From the reliable Courier:

The orderly appearance of the house showed that after the double crime was committed it was not generally plundered or ransacked…In a bureau drawer was found a gold watch belonging to the deceased husband, gold-rimmed spectacles, gold bracelets, and one or two articles of jewelry belonging to Mrs. Wickersham. A small satchel, however, in which the rancher was known to sometimes keep money, was found open, and its only contents, when taken charge of by Fred A., the nephew, was few old and curious coins. No one present was able to state whether there was much or little money in the house before the deed was committed. |

That the gold items were left might raise suspicion, but consider again the darkness problem: Oil lanterns cast light to the sides but obscure anything below, where the light is completely blocked by the base. Only by holding a lantern far above your head can someone peer downward – and if valuables are kept in a top drawer, it may not be possible to raise it high enough to see inside. Or maybe it simply wasn’t worth much; a pocket watch that dated back to Jesse’s days in the Civil War was probably of low value, and it’s doubtful Sarah kept anything but costume jewelry on the ranch.

The thieves were also pressured to finish up and leave by not knowing who else might be around and armed. Clearly they were in Ang’s room and knew the Wickershams had a house servant; perhaps there was also a stableboy in the barn or a hired man herding sheep in the hills in advance of the big storm. Which brings us to the critical question: If Ang didn’t do it, where was he all that time?

The Wickershams had just started eating supper and Ang had served everything, including the apple pie dessert and cups of tea. It was one of the few moments of the day when he had time to himself. My guess is that when the highwaymen arrived Ang wasn’t in the cabin but rather in the outhouse or barn. Once the curtain rose on the tragic play, all he could do was hide and hope he would not be sucked into it. There can be no doubt the robbers would have murdered a Chinaman without hesitation.

Ang probably remained hidden long after they left, terrified the killers might return. What he did when he finally crept back into the little house proves, to my mind, that he was not the raging mad killer as he was portrayed.

When the investigators arrived at the cabin four days later, this is how they found Jesse C. Wickersham, according to the Petaluma Courier: “…About the neck was twisted a large linen tablecloth, and underneath it several napkins. These were almost as thoroughly soaked with blood as if they had been dipped into a bucket…it was evident that the tablecloth was taken from the drawer in which the linen was kept for the express purpose of absorbing the blood…”

Incredibly, Jesse’s heart apparently kept beating even after the second shotgun blast. Someone desperately tried to stanch the bleeding. It was not a rational act because anyone thinking normally could see he was nearly dead; it was the sort of compassionate thing done instinctively by someone in shock. And the only person around to offer such a gesture of futile kindness was Ang.

What followed was hashed over in the previous three chapters, and I’ll repeat only that I doubt Ang was the man who died in the Hong Kong jail, although it’s certainly possible. But I am 100 percent certain the evidence shows he did not harm Sarah and Jesse Wickersham; trying to prove otherwise is like trying to assemble a jigsaw puzzle by hammering in pieces that don’t fit.

Overall this is the most terrible tale I have ever told. Before and after 1886 awful things occurred in Sonoma county, but the impact of what happened on that lonely ridge rippled outwards through the Bay Area, throughout California and the West and influenced people who had never before heard of a place called Sonoma county.

Weep for the Wickershams who suffered horrible deaths, but also weep for the Chinese who were abused and sometimes killed in the aftermath; weep for the communities that acted disgracefully by turning into anti-Chinese vigilantes, and weep for all our American ancestors who were willing to believe there existed on this earth a race of people who did not share our common humanity. We can all weep an ocean of tears but it still will not wash away such a mournful legacy.

1 Petaluma Courier, January 27, 1886

2 Coroner’s inquest January 22, 1886, pages 3 and 2b

3 San Francisco Chronicle, January 26, 1886

4 Sonoma Democrat, January 22, 1886

5 North county violence (or threats of same) was not limited to highway robberies. Had not the Wickersham murders taken center stage, the county newspapers would likely have been buzzing about the threat to financier John A. Paxton. Just a couple of days before the killings, a woman and man were charged with threatening him. Minnie Kasten had been stalking men connected to a Nevada bank who gave her late husband a ruinous tip on mining stock some years before. She had horsewhipped one man (the wrong guy, as it turned out) and had pulled a handgun on Paxton’s former partner (she was found not guilty by reason of insanity, in part because nobody believed her pipsqueak revolver could do much damage). Now she had shown up in Healdsburg looking for Paxton with a thug, who told someone, “That if Paxton did not look out he would get the drop on him, and then he would not be troubling anybody around there very much.” They were acquitted when it came out that Mr. Thug was a sometimes-San Francisco constable, and “that expression was used very much by that fraternity.” (So death threats were okay as long as they were just cop talk?)

6 The reward was $500 from the governor and $1,000 pledged by the Chinese merchants of San Francisco

7 Coroner’s inquest January 22, 1886 / Petaluma Courier, January 27, 1886

8 According to details in the inquest and Petaluma Courier, the shot was fired with the door slightly cracked open to prevent the gun barrel being noticed. The Courier states there were powder burns on the kitchen side of the door. But it is currently hinged in towards the kitchen; it would have to be completely open, or then opened the other way, to leave burns from the muzzle of the shotgun. Either these sources are both wrong (doubtful) of the door was rehung to open the other way at some later point in time, perhaps when an addition was added to the back about forty years ago.

9 San Francisco Chronicle, January 23, 1886

10 While few victims were injured during those stickups, a member of the Wickersham Coroner’s Jury working as a stagecoach guard was shot to death by highway robbers between Cloverdale and Preston a couple of years later.

11 San Francisco Chronicle, January 26, 1886

Read More