Remember the pursuit of O.J. Simpson in his white Ford Bronco? Of course you do; that strange, slow-speed police chase mesmerized the nation for an evening in 1994. Now flip the calendar back to 1886, when an even slower pursuit of a man suspected of a double murder transfixed the country for nearly three months, with even the White House becoming involved.

In January, 1886, Sarah and Jesse Wickersham were found brutally murdered at their remote cabin west of Cloverdale. Suspicion immediately fell upon their Chinese cook who was nowhere to be found, and who was further assumed to have skipped the country on a steamer going back to China. Supposedly he also confessed to a close friend before fleeing.

As explored in “MANHUNT PT. I: ESCAPE,” there are many serious holes in that story. The cook, whose name was usually reported as some garbled version of “Ah Tai” (he’s referred to simply as “Ang” here) had no motive to kill his employers. Word about the supposed confession in Cloverdale came from second-hand sources and the name/description of the person on the boat were very different. In sum: Not only was there actually no evidence Ang had killed the Wickershams, there was no proof he was heading for China either.

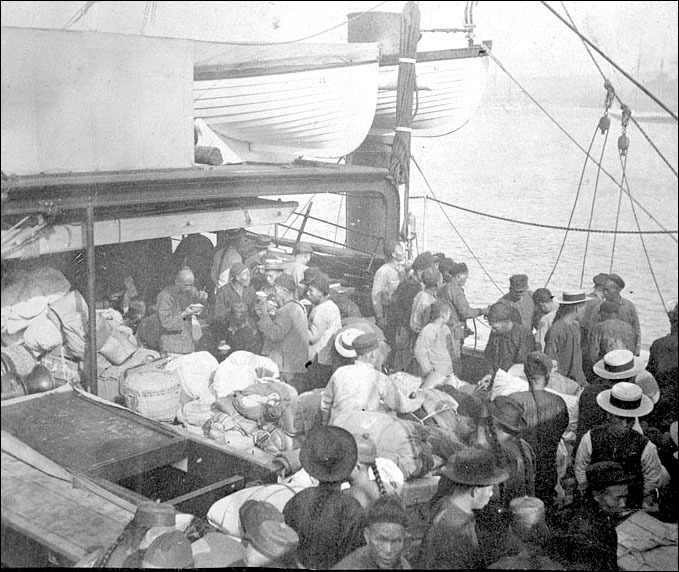

(RIGHT: Chinese passengers on a steamship probably bound for Hawaii, c. 1910-1915. Photo courtesy of the Hawaii State Archives)

It would be nearly a month before the steamship “City of Rio de Janeiro” made its first stop in Yokohama, Japan where authorities could take Ang into custody. But there were obstacles to first overcome, foremost being no extradition treaty existing at the time between the United States and Japan – more about that in a minute.

The other problem was simply getting a message from San Francisco to Japan. It was 1886, twenty years before the first trans-pacific cable. A telegram from here had to hopscotch 9-10 times across across Europe, the Mideast, India and China – and that was after it had already crossed the continent and reached the East Coast. The cost for all that was $2.50 a word, or about $85 in today’s money. A week after the murders I. G. Wickersham, the wealthy uncle of the murdered man, “volunteered to defray all the expenses for telegraphing, even if they amounted to $500.” As that would only pay for 125 words, he would come to regret that promise.1

The plan was for San Francisco Police Detective Christopher Cox to take the next ship bound for Yokohama and bring Ang back for trial. He would be accompanied by Sam Weston, a 23 year-old Petaluman who was following his father’s path and learning the newspapering trade at the Argus, where he was something of a cub reporter when he wasn’t knocking around looking for adventures. He apparently had visited the Wickersham ranch during his rambles and could recognize the suspect – but before Sam could leave for China to identify Ang, he had to go to Southern California to see if a man arrested near Fresno was Ang. Weston said no, he wasn’t the suspect.

The very next day, Japanese authorities cabled that the steamship Rio arrived and Ang had been arrested. Much excitement ensued; all that remained was for Cox and Weston to fetch him, so round trip tickets were purchased (by I. G. Wickersham?) for $350 each, or today over $24 thousand total.

But suddenly there was trouble: Japan wouldn’t allow his extradition and the excitement turned into outrage. The editor of the Santa Rosa Republican howled, “Before the last election the Democrats cried themselves hoarse over what they would do when the got in power. Well, they captured a forgerer [sic] through the intervention of the Japanese government but refuse to ask the same assistance in apprehending this pig-tailed [sic] beast.”2

Earlier that year a police detective went to Yokohama and brought back a forger who had stolen $14,000 from a San Francisco bank. The Japanese government explained that was different because the bank robber was an American being returned to America – while Ang was a Chinese national. The solution was a rather elegant diplomatic pas de deux choreographed by the State Department:

Japan would escort the Chinese man to Hong Kong, which was his intended destination anyway. Hong Kong was a British colony. There the Chinese Consul would receive the prisoner and turn him over to British authorities. As there was an extradition treaty between the U.S. and Great Britain dating back to the War of 1812, the suspect could then be held until he was taken into custody by an officer from California (because the murders were not a federal crime). The Secretary of State and President Grover Cleveland personally signed the arrest warrant.

That settled, Cox and Weston left for China on April 3. Pity no one in Hong Kong had bothered to cable them that it was a waste of time and money – the man believed to be Ang Tai Duck had hanged himself five days earlier.

News of the suicide did not reach the states until a steamer from Hong Kong berthed at the end of the month. An inquest conducted at the Victoria Jail in Hong Kong found that he hung himself from a peg high on the wall of his cell while his two cellmates slept.

The coroner’s jury did not question that his death was suicide, although they chided the British turnkey of the jail because “in view of the charge against, him, [he] should have been kept under more constant supervision.”3

While negligence by the guards is certainly the most likely reason he died, it should be noted that in the U.S. at least, Chinese immigrants accused of killing whites had a habit of turning up dead in jail. A local example happened six years earlier in Marin when a Chinese cook suspected of shooting his employer “took off his undershirt tore it into straps, knotted it, and hung himself in his cell.”4

| – | – | THE WICKERSHAM MURDERS MANHUNT II: HOW (NOT) TO CATCH A FUGITIVE SOURCES (PDF, 31 pages) |

Other bits of news included a claim that the man had confessed to the Chinese quartermaster on the steamer Rio de Janeiro – but while he was being transported from Yokohama to Hong Kong in irons, he remained silent except to protest his innocence. Nothing was mentioned about the jury confirming his identity or Hong Kong authorities presenting evidence as to whom he was.

So was the man who killed himself in Hong Kong rather than face extradition really the Wickersham murderer? The San Francisco police didn’t think he was on the ship at first, ransacking Chinatown for days in search of Ang – but since they assumed he couldn’t possibly be anywhere but in SF or on the boat, came to believe he must be a passenger on the ship.

I. G. Wickersham soon became the most prominent skeptic, writing to the San Francisco Police Chief “announcing his doubt as to the identity of the Chinaman who sailed on the steamer.” He was also concerned about the heaps of his money being spent on cablegrams to Asia, “…requesting that no further expense of international proceedings leading to the suspected man’s capture be incurred.” A year later, he asked the state to reimburse him over $2,000 related to the futile extradition.5

In Manhunt part one, it was explained that the man on the boat suspected of being Ang – and presumably, the same person who died in a Hong Kong jail – was named Ang Ah Suang and his appearance poorly matched the description of Ang circulated by authorities. So at best, we can ask the Magic 8-Ball if this was the right person and the answer will be, “Don’t count on it.”

But recall Sam Weston had been called to Fresno because the Deputy Sheriff there had arrested a man whom he was certain was Ang. The stranger appeared in the area just days after the murders and exactly matched the description of Ang, right down to the unique white spot in pupil of one eye. The man had an exit certificate allowing him to return to China and reportedly had several hundred dollars. He acted suspiciously, tore up papers when caught and was also said to be carrying a pistol.6

It’s probably safe to presume Ang arrived in San Francisco in the afternoon of January 19th and obtained an exit permit allowing him passage on a China steamship. He could not have possibly been aboard the SS Rio de Janeiro had it departed as planned that same day, but the ship was delayed for over 24 hours because of rough seas. For Ang that was good fortune; he then had plenty of time to catch it the next afternoon. But by late morning of Jan. 20 – about three or four hours before the ship’s departure – the San Francisco police and Chinatown authorities were alerted that a Chinese immigrant had reportedly murdered some Americans in Sonoma county.

There are two pressing questions: Did Ang realize he was being sought for the murders during the final hours before the Rio weighed anchor? Next, was he clever enough to anticipate that he would become a sitting duck if he boarded the ship, almost certain to be arrested on arrival in Asia?

With anti-Chinese bigotry already threatening to explode into violence, you can bet the news that someone from their community had supposedly killed whites would have spread like lightning through San Francisco’s Chinatown that morning. If Ang were there at the time, ask the Magic 8-Ball whether he knew there was a dragnet specifically looking for him – and the answer will be: “Signs point to yes.”

As to his smarts, the one fact that’s indisputable about the man who worked for the Wickershams is that he was intelligent. Besides being fluent in English, in his room he left behind a journal written in Chinese. Instead of finding incriminating evidence showing he was the killer, a translation revealed “…its contents prove the owner to have been educated far above his coolie employment. It is filled with notes of the sayings of philosophers and sages, interspersed with numerous original comments.”7

Whether or not he committed the murders (see the next and final part) my bet is Ang recognized he was in imminent danger of being captured either before the boat left or on arrival in Asia, so he took a train south, possibly hoping to disappear within the large Chinese population in Southern California. And except for Sam Weston saying the guy arrested near Fresno was not the fugitive, the weight of circumstantial evidence points to Mr. Fresno being Ang instead of the fellow on the boat. Which leads to a final question: How well did Weston really know Ang? Did the young man stay at the Wickersham place for awhile and get to know their Chinese cook, or did he only stop there briefly while riding through? His qualifications as someone who could positively ID the man were never explained in any newspaper that I can find.

Nor did Weston apparently see the body of the man who hung himself in Hong Kong. He and detective Cox arrived about a month after the suicide, and authorities told them the same details as reported about the inquest. There was no mention whether a photograph had been taken of the suspect before or after death.

But it wasn’t a total waste of time; Weston enjoyed the trip of a lifetime, completely free. “Sam Weston got back from his ocean voyage this morning,” reported a Petaluma paper in early June. “He looks as if the trip had agreed with him.”8

|

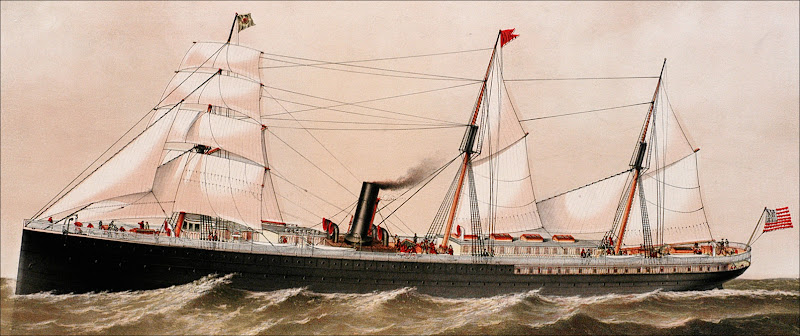

| SS Rio de Janeiro |

1 Alta California, January 27 1886 |

2 Daily Republican, February 22 1886 |

3 San Jose Herald, April 28, 1886 |

4 Sonoma Democrat, April 24 1880 |

5 Sacramento Record-Union, February 16 1886 / Alta California, February 18 1887 |

6 Alta California, February 16 1886 |

7 Alta California, January 28 1886 |

8 Petaluma Courier, June 2 1886 |