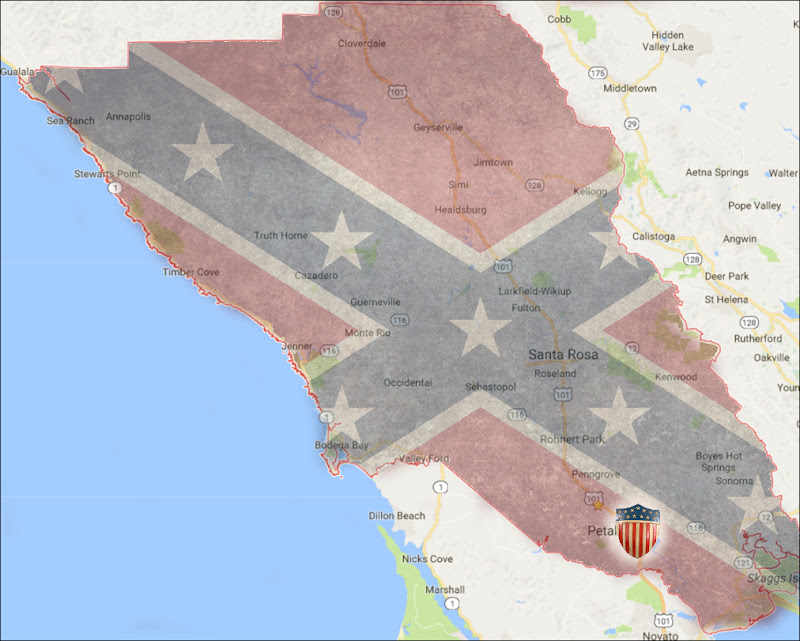

True: Sonoma county was on the Confederacy’s side during the Civil War (mostly). That fact never fails to draw a reaction when it’s mentioned here in an article and someone in the audience always gasps when it comes up in a presentation.

But the situation was also not so simple. Being pro-Confederate in California did not necessarily mean someone was for slavery in the South, and voting against Lincoln did not even reveal the voter was against the Union; there were many issues at play.

To (hopefully) clarify these issues and correct some misinformation that’s been floating around for decades, what follows is an overview of the Sonoma county homefront during the Civil War, using fresh statistical analysis and pointing out some relevant articles that have appeared here earlier.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Lincoln had support in Petaluma and some small hamlets, but never came close to winning the overall Sonoma county vote. In Santa Rosa, Sebastopol and Sonoma, Lincoln was always strongly opposed – but there is no clear explanation why those communities were so anti-Union before and during the Civil War. Five men from Sonoma county went East and enlisted as soldiers, most of them for the Confederacy. Further details on all these points are discussed below.

Although it’s been mistakenly claimed (including in this journal) that Sonoma was the only county in California that never voted for Lincoln, at least eight others cast most of their votes against him in both 1860 and 1864.1

What gave the voting records of Sonoma county significance was that Sonoma had the most people on the coast after San Francisco (Sacramento and counties in the Sierra gold country had the largest populations). Also among the never-Lincoln counties was Los Angeles – but in the early 1860s, Sonoma had more voters than them.

It was joked that Sonoma county tilted so far to the South it was called, “the state of Missouri,” due to so many early residents coming from there and other pro-secession states. But an analysis of the 1860 census for the Santa Rosa Township shows only two out of five were born in a state that opposed the Union. Although the census didn’t record where they lived before coming here, it’s probably fair to generalize and say the majority did NOT come from rebel (or rebel-friendly) places.2

Opposing Lincoln’s Republican party were Democrats taking a wide range of positions. Some hardliners hoped the South would defeat the North militarily or that Washington would give in and recognize the Confederate States of America as a sovereign nation. Moderate Democrats wanted to rejoin the Union with some sort of compromise over slavery. In Sonoma county, there were two big reasons why the Democratic message was unusually appealing – slavery and the idea that federal laws and treaties could possibly be overturned by the state.

Although California was a “free state,” slavery was widely practiced here in the years around the Civil War. One of the very first laws passed by the state legislature had made it legal to arrest Native people “on the complaint of any resident citizen” and auction them off to the top bidder for four months, while their children could be “apprenticed” to whites until they reached adulthood. North of Sonoma county, Indian villages were attacked by white raiders who kidnapped the children in order to sell them. (“The baby hunters sneak up to a rancheria, kill the bucks [men], pick out the best looking squaws, ravish them, and make off with their young ones” – Sacramento Union, 1862.) If that wasn’t bad enough, in 1860 Democrats wrote amendments to the law that kept the children in servitude until they turned 25 years old while any Native adults arrested for simple vagrancy could be sentenced to serve as an “apprentice” for up to ten years. These laws would only be partially repealed in 1863, with the status of those already enslaved not addressed until ratification of the 13th and 14th Amendments after the end of the Civil War. (More background.) And unlike the South where African-American slaves cost about $800 in 1860, underage Native American slaves in California were less than $100 and affordable to many households. The Democratic-leaning communities around here appear to have embraced the slavery laws – the 1860 census lists 17 underage “Indian servants” in the Sebastopol area including six year-old “Charley.”

Local farmers may also have been inclined to support the Democratic party because the political hot potato was anger over the government taking years to resolve land claims made by those squatting on properties which were legally still Mexican ranchos. As discussed here, Democrats here promoted their notion of “popular sovereignty,” which was the concept that every state and territory had a right to set its own laws and rules, even on slavery. In Sonoma county they piggybacked onto the politically powerful settler’s movement, which had its own definition of sovereignty – namely, it wanted California to proclaim the Mexican and Spanish land grants were “fraudulent.”

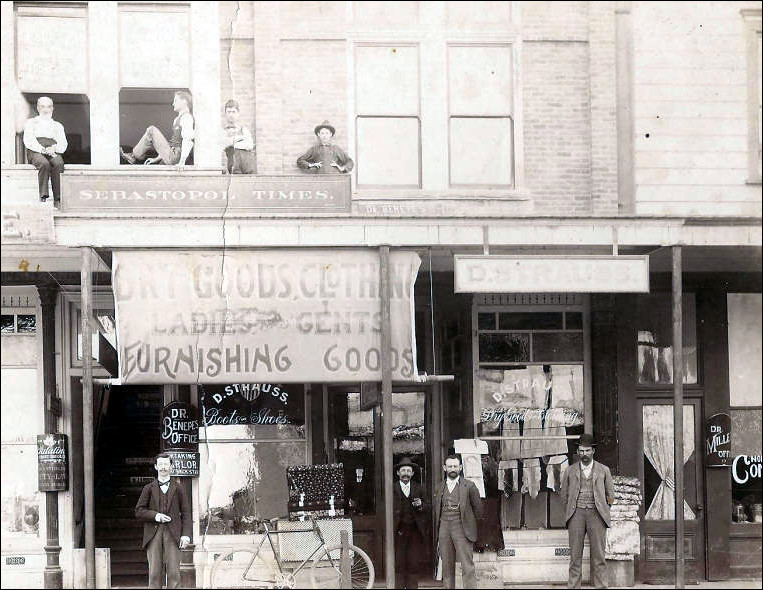

Besides election results, another way to take the pulse of a community was to look at its newspaper(s), which in Civil War-era Santa Rosa was the Sonoma Democrat, the direct ancestor of the Press Democrat. Judging by what appeared there, it would appear the town was gung-ho behind the Confederacy, even justifying African-American slavery without hesitation.

Sonoma Democrat editor Thomas L. Thompson’s paper was astonishingly racist and continued being so long after the war. There were hundreds of uses of the “n-word” during his thirty-odd year tenure, and to squeeze that many hateful slurs into a four-page weekly suggests that Thompson was not only an awful person but probably mentally ill. There’s no question he was certifiably nuts when he committed suicide in 1898 – the coroner’s jury ruled he was “mentally deranged” after ranting that the Odd Fellows’ Lodge was out to get him.

There were over a couple of dozen “Copperhead” newspapers in California during the Civil War endorsing pro-Confederacy views, as detailed below. Some (particularly the Napa Echo and Marysville Express) were quoted in the Alta and Sacramento papers as representing the views of the state’s rebel faction – but as far as can be determined by searching historic newspaper pages online, the Sonoma Democrat’s Civil War opinion pieces were almost totally ignored outside of this county, further suggesting what appeared in the Thompson paper concerning the war was not taken seriously.

As the war slogged on, Thompson only became increasingly rabid in his support of Dixie, and by the end was even reprinting propaganda from Southern papers – see “A SHORT TRUCE IN THE (UN)CIVIL WAR.” A choice line appeared in 1864, when he wrote, “the abolition party who now rule the country have become completely demonized by the infernal spirit of fanaticism with which they are possessed.” That’s a remarkably large gob of spittle to pack into just two dozen words.

| – | – | DOWNLOADArchive .zip file of Sonoma County census and election reports discussed in this article |

But judging from election returns, the people living in Santa Rosa and the other local Copperhead towns were headed in the opposite direction and became more moderate over the duration of the war. Votes are a problematic measure of public opinion (especially back then, when only white males could vote) but it’s the best measure we have.

Before the 1860 election, Thompson told readers that Lincoln was a bumbling fool who would soon cause the collapse of the Union (see “THAT TERRIBLE MAN RUNNING FOR PRESIDENT“) and the county seemed to agree with him; overall, two out of three voted against Lincoln.3 In Santa Rosa he only got about half that many votes (18 percent).

That year was an odd four-way election with both Northern and Southern Democrats in the running. Besides Lincoln, the official Democratic Party candidate was Stephen A. Douglas, who thought he could somehow forge a grand compromise to keep the United States patched together; Southern Democrat Breckinridge, who wanted to uphold slavery as an absolute Constitutional right; and third-party candidate Bell, who wanted to appease the South by ignoring the slavery issue altogether.

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION RETURNS

1860

Lincoln

Breckinridge

Douglas

Bell

For Lincoln

Census Pop.

Santa Rosa

91

205

113

94

18%

1623

Analy

217

273

88

27

36%

1604

Sonoma

84

213

29

18

24%

597

Petaluma

375

223

126

151

43%

1505

As shown in the table above, the hardliner Breckinridge won in every town except Petaluma. Votes in the Analy district seem mixed because it encompassed Bloomfield, which was nearly as large as Sebastopol at the time (!) and where they enthusiastically supported the Union. Note also that Lincoln won in Petaluma, but the combined anti-Union candidates still got the most votes there.

A clearer picture emerges from the 1861 elections, which voted for all top state offices. Now Bloomfield was separated as its own precinct so we can see that Sebastopol, Santa Rosa and Sonoma marched pretty much in lockstep. (Anecdotes about Sebastopol’s Confederate sympathies can be read here.)

The race for governor was a mirror of the previous year’s presidential election. The party-of-Lincoln Republican was Leland Stanford who was opposed by moderate and hardline Democrats: John Conness, the squishy “Union Democrat” who wanted a ceasefire followed by some sort of peace talks, and John McConnell, the (I kid you not) “Dixie Disunion Democrat” who wanted to drink the blood of Lincoln supporters, or something. The radical McConnell won in the pro-rebel towns, but Stanford did far better in those places than Lincoln had.

CALIFORNIA GOVERNOR

1861

Stanford

McConnell

Conness

Pro Democrat

Santa Rosa

164

264

77

68%

Analy

79

117

45

67%

Sonoma

127

218

10

64%

Petaluma

427

173

106

40%

Bloomfield

144

25

29

27%

1862 was a minor election year not discussed here, as there were only candidates for the state legislature – races where personal links may trump political party loyalty. Thompson complained the results were a setback for Democrats.

The 1863 election was another one for top state offices and had an interesting twist: Voters could choose a party slate for all those positions – presumably there were checkboxes for “All State Democrats/Republicans,” or similar. And so they did; county votes for all Democratic candidates hover around 1,715 and around 1,690 for all Republicans.

As shown below, this provides an opportunity to guesstimate party loyalty in the five main communities. Compared to 1860, Confederate support was weakening – even while the Republican majority in Petaluma grew stronger. Twice as many voted Democrat in the Copperhead towns while in Petaluma-Bloomfield, for every two who voted Democrat, five voted Republican.

FULL STATE TICKET

1863

Democrat

Republican

Santa Rosa

272

140

Sebastopol

142

71

Sonoma

162

84

Petaluma

148

363

Bloomfield

44

110

Also in 1863 the remaining wheels on Thompson’s bus began flying off. In his newspaper there was no longer even a (R) designation next to a candidate’s name – now he used (A) for the “abolition” party. His pro-rebel propaganda took on a new urgency; in his paper that year, Gettysburg was reported as a strategic withdrawal and not a Southern defeat.

That was also the peak year of reported activity by the “Knights of the Golden Circle,” a seditious underground rebel group mainly operating in the Midwest. It’s now believed there really was no organization behind it, being instead uncoordinated attacks and other acts of violence by anti-Yankee deplorables – that the KGC was mostly a bogeyman ginned up by Northern papers wanting to write sensationalist propaganda about domestic terrorism. Nevertheless, the fear was real and also in 1863 a “Union League” was formed in California to counter the supposed threat. Meanwhile, the Sonoma Democrat reprinted items about the KGC to bolster its “fake news” claim of grassroots opposition to the Union within Northern states. More on this topic will appear in a later item.

And that brings us to 1864, the year of Lincoln’s re-election. This time he had just one opponent – George McClellan, former general-in-chief of all the Union armies until Lincoln removed him from command after his epic military failures of 1862 including Antietam, where a quarter of the entire Union army was killed or critically injured in a single day. McClellan campaigned as the anti-Lincoln, telling voters he personally knew the president was an oafish clod who would let the the war drag on forever. Lincoln won the election in a landslide.

In Sonoma county, Lincoln fared better than he had in 1860, when two out of three voted against him (66%). This time he still lost in the county overall, with most voters (57%) picking McClellan.4 True to form in printing only good news about the South, the Sonoma Democrat never published Lincoln’s total local vote.

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION RETURNS

1864

Lincoln

McClellan

For Lincoln

Santa Rosa

208

437

32%

Sebastopol

114

191

37%

Sonoma

112

229

33%

Petaluma

559

353

61%

Bloomfield

170

67

72%

When the war began five men from Sonoma county felt strongly enough to enlist. (I am not counting Joseph Hooker, as “Fighting Joe” had not lived here since 1858.) All served as officers and two died from combat wounds. They are:

|

|

ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL GODWIN was an American settler in the Geyserville area during the early 1850s where he opened the first store. For a time he was the owner of The Geysers as well as the resort hotel built nearby, but it was still years away from becoming a profitable tourist attraction. He returned to his native state of Virginia in the summer of 1861 and rose quickly in the Confederate army ranks, briefly posted as commander of a prisoner of war camp where he was accused of cruelty (see Wikipedia). He saw combat at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg and was an acting brigadier general when he was killed during the 1864 Battle of Opequon (Third Battle of Winchester). Much false information on Godwin has been repeated as gospel in books, articles and on the internet, including the claim he was supposedly an Indian fighter and so adept at dodging arrows that a tribe agreed to sign a treaty with him. Ray Owen, who quite probably is half bloodhound, traced the misinformation back to a single 1920s magazine article about Confederate war heroes, confirming one of his favorite sayings: “Once a mistake gets into print, it takes on a life of its own.”

|

|

|

RODERICK MATHESON went East to attend Lincoln’s inauguration and when the war began he was still in New York City, where he was instrumental in organizing the California Regiment (technically, the 32nd Regiment of New York). Colonel Matheson died of injuries from the 1862 Battle of South Mountain and was the second Californian to die in the war. His body was shipped around the Horn back to Healdsburg (“the body has been embalmed, and the features have a very life-like look” – Daily Alta) and buried in Oak Mound Cemetery. His funeral cortege on November 9 from Petaluma to the graveyard was the only occasion during the Civil War when a truce was declared between the armchair warriors of Petaluma and Santa Rosa, the procession stopping in the City of the Roses for lunch and eulogy from “General” Otho Hinton.

|

|

|

ROBERT FLOURNOY resigned as Sonoma county District Attorney in July, 1861 to fight for the Confederacy. He was Captain of Company E, Arkansas 13th Infantry Regiment, and the next year the Petaluma Argus printed that his head was shot off by a cannonball (it was more than a year later before that paper reported that his head was indeed still mounted). As the rebel forces fell into disarray and dwindled, his company was consolidated with others from Kentucky and Tennessee. After the war he became an attorney in Louisville, later moving to Los Angeles where he spent the rest of his life.

|

|

|

REGINALD THOMPSON stuck close to Flournoy through the Civil War and after. They went East together, enlisted with the same Confederate regiment, and Captain Thompson took command of Company E when Flournoy was reassigned. Years later a story about Thompson was told by his commander: Their brigade was making its way on foot through a heavily-wooded area when a Union soldier stepped out from behind a tree and took dead aim at him. He stopped, stood up straight and told the soldier, “shoot, and be quick about it.” Cowed by Thompson’s bravery, the soldier lowered his rifle and allowed the “little captain” to pass. Following the war he became a Louisville lawyer like his friend Flournoy, remaining there for the rest of his life and where he became a much respected municipal judge. He was a notary public in Santa Rosa before the war but once he left, was never mentioned again in the Sonoma Democrat although he was the brother of editor Thomas Thompson. Biographical materials about Thomas refer just to his two other brothers; only Thomas’s obituary in the Press Democrat names Reginald as “another brother” far down the article in a paragraph listing their sisters. No notice of his death in 1899 can be found in any Sonoma county newspaper.

|

|

|

JUDSON HAYCOCK was an attorney in the town of Sonoma but he barely qualifies as a county resident – he lived there for only a year, and apparently came to the area in the summer of 1860 at the behest of Agoston Haraszthy to form the “Sonoma Tule Land Company,” which drained 8,000 acres of marshland on San Pablo Bay (near Sears Point, perhaps?) for farming. Haycock was commissioned as a Union army officer in 1861 thanks to a personal request to Lincoln made by his brother-in-law, California Senator Latham. He mainly served as a recruiter for the 1st United States Cavalry, but a Civil War researcher who wrote a short biography of Haycock found he was frequently AWOL, disappearing for months at a time. He was finally arrested in 1864 and dismissed from the service for “cowardice, drunkenness on duty, and absence without leave.” He returned to California and resumed his legal practice in San Francisco and Vallejo. A newspaper later described him as “a young attorney whose career, though promising at the time, never came to anything above the most severe mediocrity – if that.”

|

|

1 Voting against Lincoln in 1860: Calaveras, Colusa, Del Norte, El Dorado, Fresno, Humboldt, Klamath, Los Angeles, Mariposa, Mendocino, Merced, Napa, Placer, Plumas, Sacramento, San Bernardino, San Diego, San Joaquin, Santa Barbara, Shasta, Sierra, Siskiyou, Solano, Sonoma, Stanislaus, Sutter, Tehama, Trinity, Tulare, Tuolumne, Yolo, Yuba (3 counties were incomplete). Voting against Lincoln in 1864: Colusa, Fresno, Lake, Los Angeles, Mariposa, Mendocino, Merced, Sonoma, Tulare (6 counties were incomplete)

|

|

2 Of the 1,637 people tabulated in the 1860 census of the Santa Rosa Township, about 654 were born in secessionist states. Missouri and Indiana were also counted because of their weak support for the Union. A more accurate count is possible but would require considerable time because of the poor handwriting and unusual ad hoc abbreviations used by the enumerator, along with misspellings such as “Mare Land” and “Eutaw Territory.”

|

|

3 In the 1860 election there were 3,764 total votes in Sonoma county, with 1,236 voting for Lincoln. For the towns shown in the 1860 table above there were 2,327 total votes, with 767 voting for Lincoln.

|

|

4 In the 1864 election there were 4,686 total votes in Sonoma county, with 2,026 voting for Lincoln and 2,386 for McClellan.

|

Cᴏᴘᴘᴇʀʜᴇᴀᴅ Nᴇᴡsᴘᴀᴘᴇʀs Iɴ Cᴀʟɪғᴏʀɴɪᴀ. In answer to a correspondent, the San Francisco Flag gives the following as the list of Copperhead papers in California: Yreka Union, Colusa Sun, Marysville Express, Sierra Standard, Auburn Herald, Snelling Banner, Placerville Democrat, Dutch Flat Enquirer, Sonora Democrat, Amador Dispatch, Mariposa Free Press, Los Angeles Star, Napa Echo, Napa Reporter, Santa Rosa Democrat, Stockton Beacon, and Beriah’s Press, the Monitor, the Gleaner, the Hebrew, Irish News, Echo du Pacifique, L’Union Franco Americane, of San Francisco. There are several of the above-named sheets whose disloyalty is of a very mild form, and some of the balance are so utterly flat, obscure and devoid of any life or influence, that they hardly deserve enumeration as having any political complexion at all.

[Additional Copperhead newspapers not mentioned here were the Mountain Democrat, Merced Banner, San Jose Tribune, Placer Herald and San Joaquin Republican – je/June 2018]

– Marysville Daily Appeal, June 8 1864

Gone East. — R. C. Flournoy, Esq., has resigned the office of District Attorney of Sonoma county, and is on his way to his native State—Arkansas. A. C. Godwin, Esq., of Petaluma, has taken his departure for his native State—Virginia. Reg. H. Thompson, Esq., resigned the office of Notary Public, and has also gone East. The latter is a brother of the editor of this paper and was recently one of its editors. We are sorry to part with so valuable a portion of the community, and trust that they will return at no distant day. But theirs is a sacred mission. They have kindred there—brothers, sisters, fathers and mothers—who will need probably their presence. May they have a safe return.

– Sonoma Democrat, July 18 1861