When did we lose “old Santa Rosa”? When did we first glance into the rearview mirror and suddenly realize we could no longer see anything on the road behind us? Some of it happened in the mid 1960s, when the Carnegie library was torn down and Courthouse Square lost its actual courthouse. More was lost in the 1970s, when the Redevelopment Agency’s bulldozers plowed about 31 acres of old buildings – some beautiful and more than a few historic – to make way for that damned mall. But I’d argue a large part disappeared precisely on Saturday, May 4 1985, starting at 10 o’clock in the morning. That was when we sold off artifacts and treasures, some dating back before the Gold Rush. Or rather, the Freemasons sold it off for their own profit – all without the county or city’s knowledge or permission.

This is the story of Santa Rosa’s lost attic. All of those things were kept for a half-century in an actual attic – the top floor of the Masonic Scottish Rite Temple at 441 B street, which is where Macy’s parking garage is now.

To the untutored eye it appeared to be the sort of junky space you might have found at a grandparent’s house: There were boxes of faded photographs, souvenirs only recognizable to old-timers, objects which were precious to people very long dead but useless to anyone now. It was both a mausoleum and a loving shrine in remembrance of all things past, and there was no contradiction in that.

The keeper of these treasures was Sid Kurlander. By trade he was a tobacconist like his father before him. He was born above the family tobacco shop/cigar factory on Fourth street in 1879, and by all accounts began collecting interesting things before he could shave. Sometime during the 1930s the collection became too big for his garage (or wherever he had been keeping it) so everything was moved to the roomy Masonic attic. It’s no surprise that his collection was welcomed there; Sid was about as tangled up with everything Masonic as anyone could.1

Sid was also a Reserve Deputy, which gave him a badge with his name engraved on the back. As such he had no real duties; it was a nod to him being considered an honorary member of the law enforcement fraternity. Which brings us to the guns.

There were lots and lots and lots of guns up there in the attic and many were given to him by the sheriff or local police. There was Al Chamberlain’s gun that killed Police Chief Charlie O’Neal in 1935 and a revolver supposedly used by Black Bart. There were weapons collected by Sid or donated from people who didn’t want to have to have dangerous antiques around. There was an elephant gun, muzzle loaders, a tiny .41 caliber Spanish single-shot with a pearl handle as well as swords and machetes. All were tagged as to where they came from and their part in history.

Among other police-related artifacts: The cabinet displaying nooses from the 1920 lynchings along with the photo of the dangling gangsters. A thick book of wanted posters given to Sid by the SRPD in 1938. A pair of the county sheriff’s handcuffs from 1900. There was “beautifully made oriental opium smoking equipment” taken from a raid of Santa Rosa’s Chinese quarter and donated by Sheriff Mike Flohr. There was an engraved invitation from Sheriff Dinwiddie to the hanging of H. E. Brown on May 4, 1882. (The Governor commuted his sentence to life imprisonment.)

Nearly all of what we know about the contents of Sid’s collection comes from just two 1949 and 1976 feature stories in the Press Democrat – and those were mainly photo spreads, with little space for the writer to describe those “mementos of times that were luxurious for some and hard for others,” as Susan Swartz lyrically wrote in the latter piece.

And there were thousands and thousands of stories there begging to be told. Why did the Straub family hang on to a pair of lacy white hand-knitted hosiery from the Civil War era? On the shelves were police arrest books next to hotel registers from the Occidental and Grand hotels; Swartz was told “you’d be surprised at the names that turn up in one or the other of these.” Aaargh, so tell us!

One wonderful story which did thankfully survive concerned a little silver spoon given to Jennie Shattuck on her twelfth birthday in 1852. She and her family had sailed around the Horn and were now headed to California on a steamer, so the ship’s captain thought it would be nice to hold a party for her. It must have been a pretty swell birthday shindig, because the ship ran aground off the coast of Mexico during it.

Sometimes the PD referred to the Masonic attic as the “Kurlander Museum,” which made Sid none too happy. He was adamant he was only preserving artifacts until the city or county created a proper history museum. In the 1949 interview he said he had turned down offers from a Los Angeles museum and the San Francisco chapter of the Native Sons (NSGW) because he wanted to make sure everything stayed locally.

Also in 1949 the Sonoma County Historical Society was formed.2 That fall there were many meetings planning for an “all-out campaign” to build a history/art museum across from the fairgrounds on Bennett Valley Road. Breaking news: It ain’t there and never was.

Sid died in 1958. His Press Democrat obit mentioned he “maintained an extensive collection of historical photographs, documents, and momentoes of Santa Rosa’s early days.” But since he had never opened it to the public, people walking past the building next to the Sears & Roebuck had no idea what all was in that attic.

The collection was in limbo. A man named Spencer had the keys for awhile before Raford Leggett took over. Leggett had a very successful real estate office in Santa Rosa during the 1940s-1950s and was now in his seventies. Naming him curator seemed a perfect fit; not only did he have an interest in local history, but he was entwined with the Masonic world as much as Sid had been – perhaps more so. For better and worse, the fate of the Kurlander Collection would be in the hands of Raford Leggett for the next 25 years.

There is much to be admired in what he did during his time. He created an inventory of the collection (now lost) and gave private tours to interested clubs and school groups.

His weakness was a failure to grasp that a museum was not just an indiscriminate bunch of old stuff. Leggett donated the license plate from his family’s 1912 Rambler, an elaborate toy his father made, his mother’s wedding dress and household items such as a hand pump vacuum cleaner. There was a toolbox from a Model T (“You didn’t really need any tools, just baling wire and a pair of pliers,” Raford told the Press Democrat).

People cleaning out their attics gave him similar “heirlooms,” which he dutifully added to the Kurlander Collection. He did not see a difference in importance between Sid’s shelf of old bibles – which may contain the only surviving vital data on otherwise forgotten branches of a local family tree – with that row of butter churns he now had lining a wall.

Undated photo courtesy Dennis Kurlander collection

Despite his advancing age, Leggett was an indefatigable advocate for the creation of our current history museum. Yet a museum of sorts had existed since 1963, operated by the Sonoma County Historical Society at 557 Summerfield Road (current location of the East West Restaurant). They leased a portion of the building from Hugh Codding for $1/year; the rest being the “Codding Foundation Museum of Natural History.”

Nothing from the Kurlander Collection was exhibited there and the Society was even more eager than Leggett to accept whatnot, even soliciting donations via the PD. The paper mentioned their collection included a small ceremonial cannon, multiple shaving kits, “a photo of a Crow Indian chief by some famous photographer,” a Singer sewing machine, a lemon squeezer and, of course, old guns.

By the late 1960s the history room at the Codding museum was drawing about three thousand visitors a year and there was talk of expanding it should a new fireproof wing be added to the building. Interest in partnering with Codding to sanction it as the permanent county historical museum waxed and waned, however, depending on the current status of negotiations over the vacant sheriff’s office on Courthouse Square.

| – | – |

SLICING UP THE SQUARE Courthouse Square was split by the new street through the center with the western sliver turned into a (pathetically small) plaza, while the URA planned to sell the rest of the former county land to developers in order to pay back the $200k that was owed. There was broad public support for making it a park – possibly with a Luther Burbank statue – but downtown business interests, led by the Press Democrat, demanded the Agency go ahead with the planned sale. When the URA failed to find a buyer for the east side of the square the county sued and threatened to take back the land to sell it themselves. The lawsuit was settled in 1970 with the county accepting $50 thousand along with some undeveloped property (MORE). |

Those were also the peak years of the urban renewal squabbles over the future of Courthouse Square (see sidebar if Gentle Reader’s memory needs refreshing). The unused sheriff’s building, with its stately classical façade, was seen as a perfect fit for a museum which would combine the Kurlander Collection along with Burbank memorabilia and whatever the Historical Society had to contribute. Leggett and William McConnell formed the “Santa Rosa and Sonoma County Museum Board” to raise money for preserving and remodeling the old jail.

Our Redevelopment Overlords were not amused by the peasantry bucking their plans. Besides needing to sell the property to pay off the debt to the county, it was feared a museum might create “a dead spot” in the heart of Santa Rosa’s soon-to-be-bustling (!) business district. Finally killing the dream was an engineering estimate it would cost up to $200k to bring the building up to code and retrofit it for a museum – which would actually have been a bargain, as it cost 3x more to just relocate the former Post Office building.

In the following years Juilliard Park was mentioned as somewhere a museum could be built, but there was little energy in trying. Then came the 1976 Bicentennial and with it a surge of interest in all things historic. The Historical Museum Foundation of Sonoma County was formed with Leggett named as its first president. The Foundation was given $1,500 by a county commission and there was much ado about a fund-raiser at the Occidental Hotel which exhibited items – presumably from the Kurlander Collection – which would appear in some future museum.

The historical crowd had their eyes set on (somehow) obtaining the post office building the URA had slated for demolition, but there was no clear path forward. Hugh Codding proposed to buy it for a museum and leave it where it was, with the mall developer building a three-story parking garage around it.

Having been disappointed so often before, the Foundation said in 1978 they would settle for a downsized museum in the stonework Railway Express building at Railroad Square (now A’Roma Roasters) and the City Council pledged $250k towards that. But in a burst of hometown verve worthy of a three-hanky Hallmark Channel movie, in the spring of 1979 donations poured in and there was suddenly enough money for the Foundation to acquire and move the old post office.

Come “Museum Day” (Jan 12, 1985) Sonoma County finally had a real history museum when the thoroughly revamped building, now moved 850 feet northwards, had its gala opening. It was a cause for celebration, but the joy for historians was short-lived – within four months the celebrated Kurlander Collection, which Sid had started before the turn of the century with the dream it would be the foundation of just such a museum – would be scattered to the winds.

That the old post office would stay around long enough to become our history museum was never a sure thing until the end of 1978; the mall developer and the Redevelopment Agency were itching to see it demolished. Agency member George Sutherland said he considered the post office an “abomination” that the misguided public had turned into a “sacred cow.” The Agency grudgingly voted to preserve it only because it was already listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

There was also public interest in saving the Scottish Rite Temple but it was a less noteworthy building and not on the Register, so it was torn down the same year. Had it been similarly preserved and moved elsewhere the Kurlander Collection might have survived intact.

At some point inbetween the vague plans to create a museum at Juilliard Park or A’Roma Roasters, Sid’s grandson, Dennis, recalls he and his father Herb approached the Freemasons. They asked for the neglected collection to be returned to their family with the notion of themselves creating a Kurlander Museum of some sort. Sorry, it all belonged to the Masons, they were told, but should Scottish Rite have to move they were promised it would be kept together at their new place and placed on display. So when the building was slated for demolition all that Sid had collected over his lifetime was crated up and placed in storage.

Fast forward to Monday, May 6, 1985. Dennis Kurlander picks up his phone and the caller is a friend who tells Dennis he bought old photos and other items at a big antique auction over the weekend, later noticing some were labeled with the name “Sidney Kurlander.”

The Freemasons had sold the Kurlander Collection as part of a fundraiser to help pay off the mortgage on their new Highway 12 Masonic Center.

“If I had known this on Friday,” Dennis angrily told Gaye LeBaron, “I would have had my lawyer stop them.”

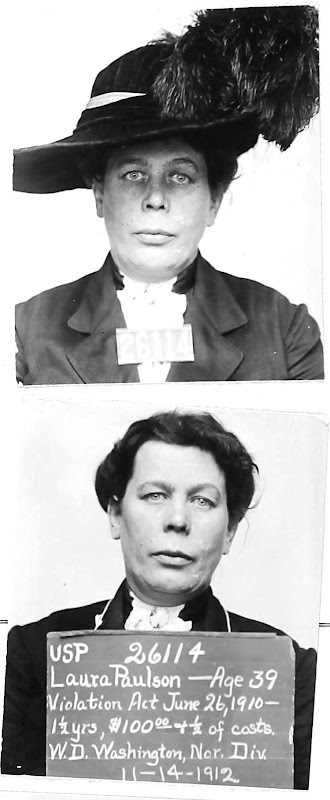

(RIGHT: Auction announcement from the Press Democrat, May 3, 1985)

(RIGHT: Auction announcement from the Press Democrat, May 3, 1985)

Gaye wrote four columns about these doings yet no reporter from the Press Democrat was assigned to investigate, even though the Kurlanders were seeking counsel about suing the Masons – had they simply filed such a complaint it would have been a major news story with an impact far beyond county lines.

What follows is drawn from her columns May 10-16 [my additions are enclosed in brackets].

Although Sid had bequeathed the collection to the Scottish Rite, the Kurlanders said it was given with the express intent it should be kept intact and made available to the public. Walter Eagan, chairman of the Masonic board of trustees, told Gaye LeBaron they “didn’t know there were strings attached…we never realized we had a obligation.”

The auctioneer told Gaye he was likewise unaware they were selling off an important collection, but made a defense that the Kurlander items were only about twenty percent of the things sold that day; the Masons had put out a call for all lodge members to donate their antiques and collectibles for the mortgage sale. [The auctioneer did not say how much of the proceeds came from the Kurlander Collection, but given the rarity of the items – particularly the firearms – it certainly would have brought in a helluva lot more than the other contributions, which were likely garage sale quality.]

LeBaron spoke to Raford Leggett and wrote he did not seem concerned the collection had been sold piecemeal, and told her it was done because there was simply no room in the new building to house the collection. [At the time Leggett was 91 and nominally involved as a director emeritus of the Foundation, which operated the new museum. He did seem to still have focus; just a few days before the auction he gave a well-received talk about his memories of the 1906 earthquake.]

What peeved Gaye LeBaron and others most was the collection hadn’t been given to the museum, as Sid had clearly wanted. “We understood the museum got some stuff,” Eagan told her. “We assumed they got the things they wanted.” The Masons had contacted museum curator Dayton Lummis in advance of the auction and allowed him first dibs, but the museum – newly opened and with a shoestring budget – paid the Masons $1,800 to claw back just a tiny bit of the collection. After Gaye’s first column appeared, a few locals who bought items at the auction without knowing the backstory came forward and donated their purchases to the museum. [A portion of what the Museum was able to save can be seen cataloged under “Kurlander Collection” and “Scottish Rite Society.”]

Also galling was the Masons had offered the entire collection to the county library. Director David Sabsay told them they would “take the historical things, but that we wouldn’t have a place for the moose heads and stuffed birds.” The Masons’ response was that it was all or nothing. [Their proposal was probably to sell the collection, but LeBaron didn’t specify. It also appears Sabsay was mistakenly thinking the Masons were offering him the Codding Museum, which besides the Historical Society exhibit did indeed have stuffed big game animals and birds in another section. Dennis Kurlander doesn’t recall taxidermy items from his grandfather’s collection.]

The whole episode filled the historically-minded community with anguish and anger. Gaye LeBaron wrote some felt the Freemasons should unring the bell and track down all the Kurlander items and buy them back. She commented they should at least refund the $1,800 which was obscenely paid by the museum.

As for the Kurlanders, Dennis spent weeks afterward prowling antique stores and contacting dealers, spending thousands trying to rescue what portions of the collection he could. He told Gaye the issue was never about trying to claim the auction sale proceeds. “It isn’t the money,” Dennis said in 1985. “It’s that this is an insult to our family.”

| 1 Aside from being a member of the Santa Rosa Masonic Lodge as a Knight Commander of the Court of Honor, Sid Kurlander was a 33rd degree member of Scottish Rite, in the local Order of the Eastern Star, belonged to the Shriners Temple in Oakland and was president of the Shrine Club here. According to his Press Democrat obituary, “he devoted much of his time to fundraising activities in behalf of the Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children in San Francisco.” |

| 2 There were earlier “Sonoma County Historical Society” groups which came and went as early as the 1870s. While well-intended, each appears to have fizzled out quickly. The 1949 incarnation went dormant after a couple of years and the current society was formed in 1962. |