William Cox was having lunch at home when he heard the whistle of his train. “Toot, toot,” it blew as the locomotive left Sebastopol bound for Santa Rosa.

|

NB to Gentle Reader: Yes, I am quite aware the whistle of a steam locomotive in 1900 did not sound anything like “toot, toot,” but I am quoting here directly from the Press Democrat coverage which otherwise is a darn good piece to read, so let’s cut the paper some slack on this.

|

As William was the train’s engineer and he was clearly not aboard it, he assumed Eugene, who kept the engine stoked with wood, had received an urgent order from the California Northwestern railway station in Santa Rosa to bring the train there.

But Eugene Ellison was not in the cab either. The man with his hand on the throttle was Will Thompson, who everybody called “Brick.” He was 31 years old and had never driven a train before. He was also insane.

“Toot, toot,” Brick sounded the whistle at every crossing, just as William always did. Section hands doing track maintenance near Llano Road were having lunch as well. They didn’t look up when engine No. 11 passed by and just assumed Engineer Cox had received an urgent order from the California Northwestern railway station in Santa Rosa to bring the train there.

Witnesses later said Brick was pushing the train up to 50MPH, which was faster than it had ever gone before. He made the trip to Santa Rosa in twenty minutes, and it only took that long because he had to stop near Fulton Road to wait for the steam gauge to come up to pressure after shoving in more wood.

This next bit is fun because the PD almost never printed dialogue in those days, and here we learn our ancestors spoke fluent Victorian-era slang.

A boy on his bicycle rode up to Santa Rosa Station Agent Joe McMullen and said, “Say, Joe, No. 11 is coming in.”

“What’s the josh?” McMullen asked the boy. “Straight goods,” the kid replied. “Here she comes.”

McMullen watched in astonishment as the steam engine pulled into the south end of the railroad yard and a strange man popped out of the cab. “Who brought over the engine?” He asked Brick, apparently thinking Cox or some other trained engineer must be in hiding.

“I did,” answered Brick before strutting away down Fourth Street, “and don’t you let her go.”

Apprised of the unusual hijacking, the sheriff and city marshal were also flummoxed and likely wondered if there was more to the story than it seemed – after all, people don’t take off with trains. A posse was formed, which meant at the time that they spread the word to be on the lookout. From the PD: “Needless to say, the news of the occurrence caused no little stir in this city and ‘the man who stole the engine’ was pretty forcibly talked of.”

Meanwhile, Brick was enjoying a repast at the Chicago saloon on Fourth Street. When he stepped out of the bar Deputy Sheriff Tombs (yes, his real name) arrested him. Brick pulled a carpenter’s hammer from his pocket and tried to whack the officer in the head, but City Marshal Holmes stopped the assault by grabbing his raised arm.

That afternoon a Press Democrat reporter spoke to Brick at the jail. He paced in his cell, ranted about the deputy touching him without a warrant, and insisted he bought the train fourteen years ago. “When [the president of the railroad] knows of it, it will be all right.”

He was examined by the lunacy commission – an agency we certainly should revive, particularly in election years – and sent to the asylum near Ukiah for a time. It’s noteworthy that his father requested his commitment, possibly as a legal maneuver to avoid Brick being sent to prison for stealing the train and/or trying to hammer a deputy.

Details later emerged that Brick’s joyride almost ended in disaster. As he stepped off the train in Santa Rosa he left the throttle open, and, as the PD noted, “When the locomotive arrived here the water was nearly exhausted. Had the man run the engine much further it is very probable that he and it would have been blown to fragments.”

It also came out that he was a “dope” addict at the time, which in his case meant opium. After his release from the asylum he remained in the Ukiah area, where he worked at a livery stable and reportedly began using drugs again. There in 1905 he attacked the owner with a razor and fled to Sacramento, where he shot a policeman in the leg.

Brick was spotted in Santa Rosa a few days later – his family lived in the area – before he returned to Sacramento. There he accidentally shot himself in the hip and died of sepsis.

The only obituary to be found was in the Santa Rosa Republican, and read in part: “He was 36 years of age and was considered somewhat demented, which fact brought him into prominence several times as the principal in a number of escapades.”

FROLIC WITH STEAM

A Sebastopol Engine on a Flying Trip

A MAN’S WILD RIDE

While the Engineer Dined Another Took His Place Unasked

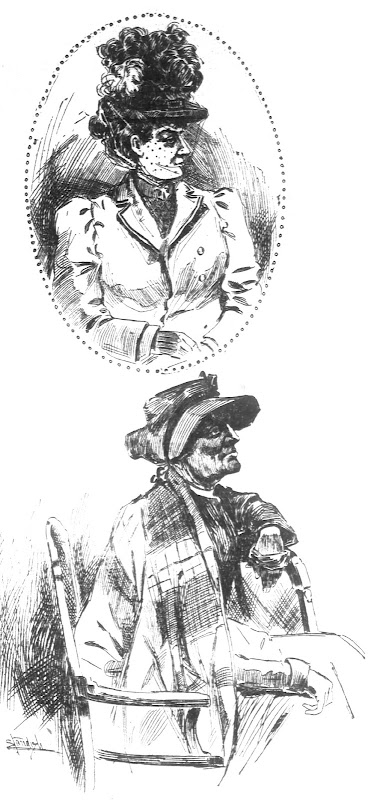

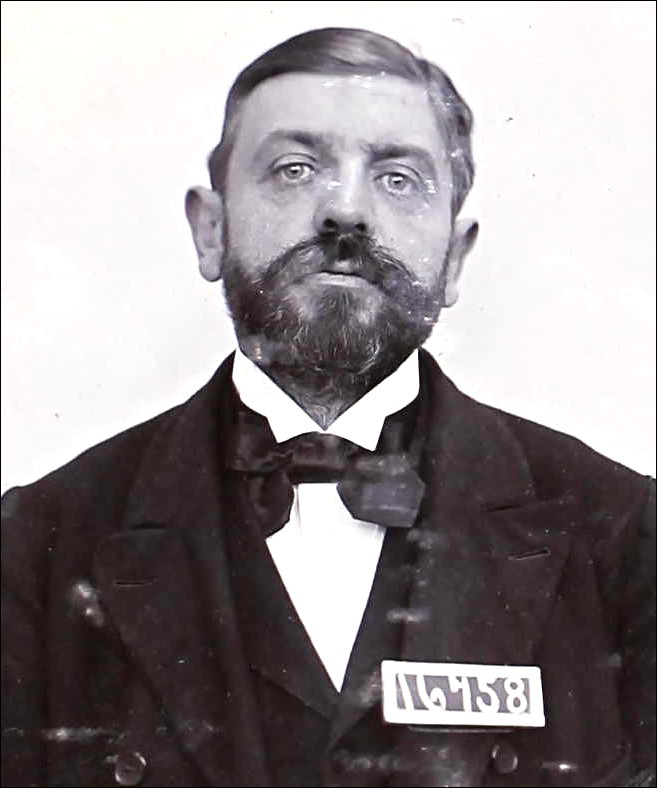

“Brick” Thompson’s Escapade on Monday — When Arrested Tries To Assault the Officer – A Charge of InsanityIt is rather an uncommon thing for a man to be able to “steal” a railway locomotive and run it as he desires, especially without harm resulting to himself or some one else, or even to the engine. Yet Will Thompson, or as he is familiarly known, “Brick” Thompson, did this Monday afternoon.

Fate was certainly with him when he coolly stepped into the cab of the locomotive used on the Sebastopol branch of the California Northwestern railway, pulled the lever and opened the throttle and started, monarch of all he surveyed down the track to Santa Rosa. At the first crossing he gave the accustomed “toot, toot,” just as Engineer Cox, the regular hand at the throttle, does. By the way, Mr. Cox was in the act of complimenting his wife on the excellent lunch she had provided for him, when he heard the warning whistle of “No. 11” as she sped down the track. He thought, however, that a hasty call must have come from Santa Rosa for the engine and that Fireman Ellison had “taken her over.” When he and others learned what had really happened their astonishment can readily be imagined.

Acting Engineer Thompson made “No. 11” break several records until he was well out of Sebastopol and when crossings were reached the warning whistle rang out as usual. When near the Llano school house he slowed down for a short distance. The section men, who wore eating their lunch near the LaFranchi place, paid no particular attention to the oncoming locomotive, thinking that Engineer Cox had been summoned to make a special trip. But somehow or other Thompson in the cab paid particular notice of them for he sped “No. 11” at such a terrific rate that they could not see who was in the cab. Once or twice after this the self-constituted engineer slowed down a little and started up again just to see what the engine could do. When Santa Rosa was reached steam began to give out so that his perilous ride had to end.

Mervyn Donahue rode on his wheel hurriedly to the depot. Espying Station Agent Joe McMullen, he accosted him thus;

“Say, Joe, No. 11 is coming in.”

“What’s the josh” inquired the station agent.

“Straight goods,” replied the other, “Here she comes.”

Station Agent McMullen so far recovered his astonishment to be able to ask the strange engineer as he drew up near the depot, “Who brought over the engine?”

“I did, and don’t you let her go,” Thompson replied then walked hurriedly away up town. The marshal’s office and sheriff’s office were instantly apprized of the unheard-of theft of a locomotive and in a twinkling a posse had started to round the man up.

Just as Thompson stepped out of the Chicago saloon on Fourth street near the corner of that street and Exchange avenue, Deputy Sheriff Tombs placed him under arrest. The man ran his hand into his pocket and quick as a flash produced a carpenter’s hammer, swung it aloft and it was about to descend on Mr. Tombs’ cranium when City Marshal Holmes held the uplifted hand in a firm grasp and prevented any damage. Tho man was then taken to the city hall.

Engineer James Donahue was on his way up town just about the time when the engine arrived at the depot. It is true that he was dressed in his Sunday best, but he climbed into the cab and ran the engine back to Sebastopol in time to bring in the afternoon train.

Needless to say, the news of the occurrence caused no little stir in this city and “the man who stole the engine” was pretty forcibly talked of. Such a person had never been heard of in these parts before.

A Press Democrat reporter saw Thompson later in the afternoon at the county jail.

When asked why he took the engine he replied: “I own the engine. I bought it a number of years ago. When Foster (meaning the railroad president) knows of it, it will be all right.”

He then made some strange remarks about having the officers arrested for touching him without a warrant. While he was speaking he moved about all the time, walking hither and thither about his cell. His conduct was such that those present at the interview were led to believe that probably the hand of an insane person held the throttle on that run from Sebastopol to Santa Rosa. The man’s own father, who is a respected citizen of Santa Rosa, says that his son is insane. He was very much grieved when he signed his name to a complaint alleging that he was insane. He told Judge Brown Monday afternoon that up to a month or so ago “Brick” used opium freely. All of a sudden he stopped taking the drug and it is supposed that this resulted in his mind becoming affected. At one time he also used considerable morphine and was under the care of a physician.

That Thompson’s wild ride ended as luckily as it did is a matter for congratulation. When the locomotive arrived here the water was nearly exhausted. Had the man run the engine much further it is very probable that he and it would have been blown to fragments. From a legal standpoint the mere running away with the engine would probably mean prosecution for malicious mischief or trespass. When asked Monday evening whether the man would undergo an examination on the insanity charge District Attorney Webber said that he could not state yet. He may be charged with assault with a deadly weapon for his attempt to hammer Mr. Tombs.

– Press Democrat, February 21 1900

A WILD RIDE ON AN ENGINE

Mad Man Takes a Spin on the Sebastopol Locomotive.

Opened the Throttle and Sent Old No. 11 Across the Valley at a Rapid Rate.It is only once in a life-time that we hear of the theft of a railway locomotive, and such an occurrence has a natural tendency to stir up a little interest and excitement. For the first time in the history of the California Northwestern Railway one of the Company’s engines was stolen last Monday.

Shortly after twelve o’clock a man about thirty years of age walked into Sebastopol from the direction of Freestone. Near the cemetery, about a mile west of town, he met William Mather, to whom he stated that he was going to make a speedy trip from Sebastopol to Santa Rosa and that only twenty minutes would be consumed in the seven-mile cross-country run. It cannot be denied that the stranger executed his boast according to schedule. He walked down to the depot, boarded the engine which had been left standing near Julliard’s winery, opened the throttle and was soon heading toward Santa Rosa at a mighty clip. Station agent Harvey was in the depot building at the time and the train hands were at home enjoying the noon-day meal. When the locomotive passed over the laguna trestle the noise was distinctly heard up town. Most people thought the train men were going over to Santa Rosa to do some switching before making the regular afternoon run. Engineer Cox, fireman Ellison and conductor Corbaley realized that something was wrong and after holding a brief consultation they decided to wire a “lost, strayed or stolen” message to Agent McMullen at Santa Rosa. In the mean time old No. 11 was speeding over the steel rails at a pace she had never struck before. At every crossing the man in the cab opened the whistle valve to give warning of his approach. People who saw the iron horse crossing the valley say that the trip was made at a fifty-mile rate of speed. Between the Llano school house and Wright’s crossing the steam supply became exhausted and the locomotive came to a stand still. With the familiarity of a veteran fireman the stranger at the throttle applied the brakes, filled the furnace with wood and waited until the steam gauge indicated that the trip could be continued. Then he set the machinery in motion again and a few minutes later the engine and its passenger made a flying entrance into the railway yard at the County Seat. There was a large and appreciative audience at the station to witness the arrival of the lightning special. The locomotive was stopped in front of the depot and the would-be engineer left the cab and walked up town. He carried a large hammer and not one of the spectators seemed inclined to molest the privileged character as he sauntered up Fourth street. Before many hours had passed the entire force of Santa Rosa’s official dignitaries struck the trail of the locomotive excursionist and he was located in the Chicago saloon on Fourth street. The officers experienced considerable difficulty in landing their man in the county jail.

When asked why he took the iron horse without permission, the adventurer stated that he purchased the engine fourteen years ago and had a perfect right to run it as often and as fast as circumstances necessitated.

The man who created such a sensation in railway and police circles is William Thompson, son of a Santa Rosa carpenter. He has been working for some time past on Sam Allen’s farm on Pleasant Hill. It is said that for years the young man has been addicted to the opium habit and he is a mental wreck. The general opinion is that he is insane and he will be examined by the lunacy commissioners. The engine was brought back to Sebastopol Monday afternoon in time for the regular 2:50 trip. No damage was done by the extra run.

LATER.

Thompson was examined by two physicians and they reported that his mind is temporarily deranged.

– Sebastopol Times, February 21 1900

Examined for Insanity

William Thompson, whose sensational ride from Sebastopol to Santa Rosa aboard “No. 11” Tuesday caused such a sensation, was examined yesterday upon a charge of insanity, preferred by his father. The examination took place in the county jail, Drs. J. W. Jesse and S. S. Bogle acting as commissioners. After subjecting the prisoner to a rigid questioning, it was decided to postpone the decision for a few days as it is thought his present condition is but temporary.

– Press Democrat, February 24 1900

SANTA ROSAN IS IN TROUBLE

“Brick” Thompson Who Stole the Sebastopol Engine Five Years Ago Shoots PolicemanR. M. Thompson familiarly known as “Brick” Thompson who according to the dispatches from Sacramento shot Officer Bert Callahan in the thigh last night after he had run amuck is well known in Santa Rosa and in this vicinity.

About five years ago Thompson boarded the engine of the Sebastopol branch of the California Northwestern at Sebastopol and ran it over to the county seat. He knew nothing of the mechanism of the locomotive but managed to start it and once started it kept going until the steam gave out. This happened at the south end of the railroad yards in this city and when the locomotive came to a standstill Thompson alighted without shutting off the throttle. After he stepped from the engine employees of the company who investigated the unexpected entry of the engine into the railroad yards caught him and detained him until he could be placed under arrest.

Thompson was believed to be insane and the freak of stealing the engine was characterized as the result of a disordered mind caused by using “dope” He was sent to the hospital at Ukiah and afterward was discharged as cured.

At Ukiah he made a vicious and unwarranted attack on Henry Smith proprietor of a livery stable there where he was employed and attempted to carve Smith with a razor. This was the result of his craze from using dope. Smith entered the barn and without a word of warning or any provocation Thompson jumped at him with an uplifted razor. That Smith escaped instant death is regarded as miraculous as he was unprepared for the onslaught.

Thompson passed through this city a couple of days ago and was recognized by Oscar Smyth at the local depot. After the episode of stealing the engine Thompson dropped from sight here by reason of his incarceration in the asylum. He was not heard from again until his attempt on the life of Smith at that place. His latest escapade will probably result in his being incarcerated again.

– Santa Rosa Republican, February 10, 1905

Will Go to a State Hospital

Contrary to the faintest hope, about half-past 4 o’clock yesterday morning, William Thompson, who took morphine the previous evening to end his life, began to revive, and continued to improve. His mind, weak at the time he took what nearly proved a fatal dose, was worse yesterday, and last evening two of the lunacy commissioners held a consultation. Probably today or tomorrow Mr. Thompson will be removed to the state hospital at Napa.

– Press Democrat, March 11 1899