If a time machine is ever invented, lord help Santa Rosa’s 1960s decision-makers; there will be mobs of howling Facebookers chasing them through the streets for what they did to this town.

Those who hang out in local history and nostalgia social media often write about downtown Santa Rosa in that era as if it were a crime scene; a vintage photo of a picturesque building now demolished, a scene of streets crowded with shoppers will draw tearful emojis and bitter comments. How did all this come to disappear? We know the answer: It was the outcome of the town’s gung-ho embrace of urban renewal schemes, which are the subject of this series, “Yesterday is Just Around the Corner.”

(This article covers only “Phase I” of Santa Rosa’s redevelopment in the 1960s, when the urban renewal area was limited to the 40 acres between Sonoma ave. and Third street, and from Santa Rosa/Mendocino avenues and E street. Events leading to construction of the Santa Rosa Mall were Phase II and III during the 1970s and will be covered later.)

Other cities and towns climbed aboard the redevelopment gravy train – it was free federal money after all, and the government wasn’t too picky about how it was spent. But few communities were willing to go as far as Santa Rosa and gut so much of their downtown core.

One reason this is so crazy-making for us today is because there was no compelling reason to declare most of the downtown “blighted,” which was their excuse for wiping out entire blocks and more than a hundred historic buildings. The movers ‘n’ shakers of Santa Rosa saw the opposite – downtown was economically blighted because their projections estimated the taxable value of the area after redevelopment would be at least three times greater.*

They were also true believers that anything new was better than old. In a 1961 editorial the Press Democrat dismissed all the old buildings as “substandard” and said tearing them down would “…serve the Santa Rosa of today and the future instead of continuing to be a deteriorating hodge-podge that ‘just growed’ over the past 75 years or so.”

Steering the redevelopment ship was the five-member Urban Renewal Agency (URA), which was created by the City Council in 1958. Its executive director and the appointed members wielded enormous power (including the ability to condemn land using eminent domain without a public hearing) yet faced little criticism except from one persistent fellow named Hugh Codding – more about him in a minute. What the public heard instead was enthusiastic approval from the Council and city staff and particularly the PD, which was the URA’s most ardent cheerleader. The paper leaned hard on the notion that the blighted area really was studded with eyesores, and good riddance; there was a photo they liked to use showing a ramshackle house badly in disrepair with a sagging porch – while neglecting to mention one of the first places to be demolished would be Luther Burbank’s house.

Redevelopment programs became infamous for graft and corruption but I don’t find a whiff of that happening here. While the URA was biased toward particular developers and clearly treated Codding unfairly, I fully believe everyone’s motives were well-intentioned – that they expected the result of their labors would truly create a city beautiful. Of course, very little worked out as well as they expected and they ended up creating a city regrettable. To paraphrase the great disclaimer at the start of the movie, Fargo:

| This is a true story. The events described here took place in Santa Rosa, California. Out of respect for the survivors of those times and their families, keep in mind the decision-makers back then were not fools, dunderheads or venal crooks, though some of their choices seem glaringly stupid today. But hey, it was the 1960s, when everybody was a little nuts. |

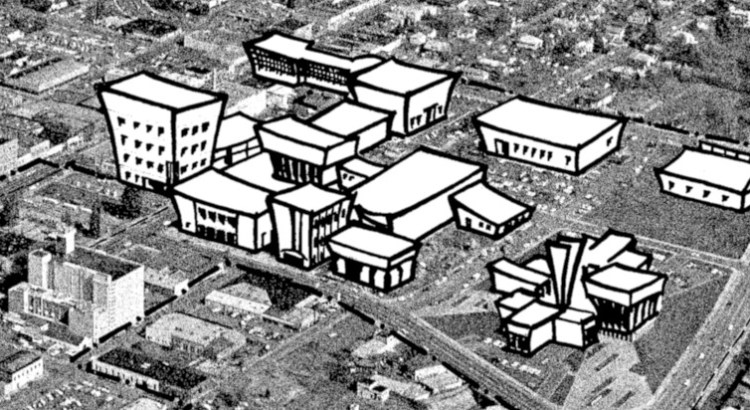

Santa Rosa’s Big Urban Renewal Adventure kicked off in 1960, when the city tapped some of the URA’s government money to hire New Jersey urban planning experts to come up with ideas on what they should do with the six blocks to be redeveloped. They developed a model that everyone here loved like a warm puppy – it was so popular they had to schedule showings of it in bank lobbies and store windows.

Their model shows a fully restored Santa Rosa Creek greenway with the city hall and state building on its southern bank (an earlier drawing shows the courthouse and jail there, before it was decided in mid-1960 to rebuild at the county administration center). There was plenty of parking spaces, a big department store and several mixed retail/office buildings.

Naturally, Santa Rosa threw it all away.

No, strike that – they kept the parking lot next to the library and the parking garage at Third and D.

Without a master plan the URA couldn’t provide a rudder for what should be built and where, aside from vague expectations there should be a new city hall, a major department store (or two) and a “shopping center.” Read that again, slowly: The only planning provided by the city was what to condemn and demolish, leaving it to the developers to shape how downtown would look and function. The Press Democrat had welcomed urban renewal as an opportunity to rid Santa Rosa of its “hodge-podge” appearance, but we were preparing to hodge-podge it up again, only now with plenty of very undistinguished office buildings.

(RIGHT: The 500,000 sq. ft. proposal for downtown Santa Rosa from Megapolitan Corp. The street glimpsed at the top is presumably Sonoma ave.)

(RIGHT: The 500,000 sq. ft. proposal for downtown Santa Rosa from Megapolitan Corp. The street glimpsed at the top is presumably Sonoma ave.)

In place of the master plan there were four proposals made to the URA in 1963. (A reminder again that this was for the six blocks directly south of Courthouse Square, not the current location of the mall.) Two developers pitched conventional shopping centers with no big anchor stores – one used the top floor for professional offices. An ambitious bid from the Megapolitan Corp. of Los Angeles called for a massive shopping center which was virtually an indoor, self-sufficient town, sans housing. The bizarre plan called for a “European opera house” with seating for 1,500 that “could accommodate full broadway, concert, opera, and ballet productions” a nightclub, two “theater bars,” dance and health studios, laundry and dry cleaning shops, a supermarket, drug store, billiard hall and a “host of specialty tenants.” (Whew!)

The winning proposal in 1964 came from the Santa Rosa Burbank Center Redevelopment Company (called here “SRBCRC” to avoid confusion with all other things Burbank). This was a financing consortium put together by Henry Trione and his friends, not planners or architects – they hired top-notch Bay Area designers to come up with actual plans. Their original presentation included two department stores plus a “Civic Tower” on Courthouse Square straddling a sunken roadway, as discussed in the article on the development of the city hall complex.

That the URA made a sweetheart deal with Trione’s group for ownership of the entire 40 acres irked Hugh Codding no end, mostly because the agreement was made with the price yet to be negotiated at some future date. Once he became a City Councilman, Codding would needle the URA directors by sarcastically asking if SRBCRC had made a downpayment yet.

But despite the URA’s founding promise that redevelopment would draw big-name stores to downtown Santa Rosa, it seemed no companies were willing to take a chance. It was rumored that Macy’s was interested; nope. J.C. Penny? Pass. Emporium? Sorry. SRBCRC hired another set of architects to draw up new layouts. “The success of any of the plans was highly speculative,” Trione wrote in his autobiography. “Potential buyers were very cautious.”

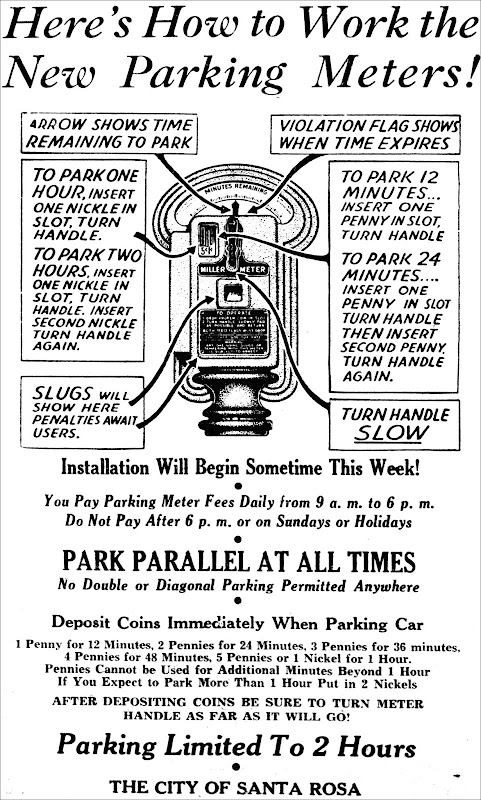

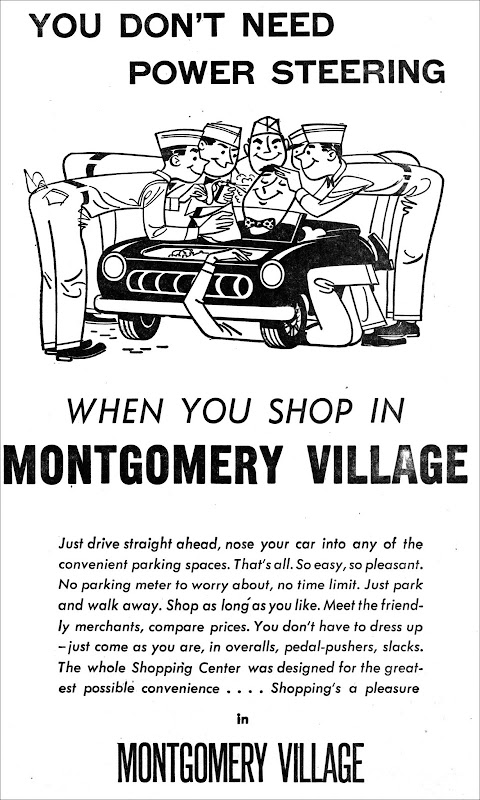

It wasn’t that those companies were cautious about building new stores – it was that they were leery about Santa Rosa’s downtown; their location scouts couldn’t help but notice parking was a headache (and not free). The uncertain status of the redevelopment area meant their future neighbors could range from an upscale jewelry store to a smelly fast food joint, and ongoing construction would keep the area dusty and noisy for years to come. No, a smarter bet would be to build a department store in a spanking new shopping mall with none of those drawbacks. Coddingtown, for example. And so they did.

Looking ahead, Trione and his company built offices, banks and government buildings (which, I imagine, few of us have ever had reason to visit). The only retail space was a new home for the White House department store. Phase I of the urban renewal project did not make Santa Rosa a more beautiful place, nor did it give shoppers more reasons to go downtown, nor did it add appreciably to the city’s tax base.

But in the autumn of 1965, the Press Democrat’s editor Art Volkerts imagined it was the start of a glorious transformation. In a puff-piece “URA Holds Promise in Heart of Santa Rosa” he wrote,

| …What will this mean to Santa Rosa? Well, it will mean more tax revenues to help pay for the city’s expanding services. It will mean bright, new buildings rising in an area which was fast becoming a civic blight…it now seems certain that the URA project will indeed be a flower worthy of maturing next to Santa Rosa’s beloved Burbank Gardens. |

Others more clear-eyed saw it meant 37 businesses had been displaced and 44 families plus 43 single individuals had lost their homes. For the next few years there would be forty acres of vacant lots scraped down to the dirt waiting for all that greatness which would not come.

| * “In its present run-down condition, the Santa Rosa urban renewal area is assessed at $859,000. The least favorable of the several forms which redevelopment could take will result in real and personal values assessed at $2,413,700.” Press Democrat editorial, July 17, 1961. By 1965, the PD was claiming the current value was about $3 million and should be worth over $12M. |