The forecast was cloudy with a chance of doom.

In the final weeks of 1919, no one in Sonoma county knew what would happen when Prohibition officially began on Jan. 17, 1920. Was it just token political gimcrackery to appeal to a certain class of voters, or was this really the end of the wine industry in the United States? Our wine-making, grape-growing and beer-brewing ancestors already had endured a year of being whipsawed by good/bad news, and now the frightful precipice yawned directly before them.

For those new here, some background will help: This is the third and final article about that bumpy road to national Prohibition. Part one (“Onward, Prohibition Soldiers“) covers local efforts by the “dry” prohibitionists to close or restrict saloons in Sonoma county in the years following the 1906 earthquake. Part two (“Winter is Coming: The Year Before Prohibition“) picks up the story in 1918, when the notion of prohibition has expanded beyond simple demands for temperance into a tribal war between rural, conservative and WASPy sections of the nation against those who lived in areas which were urban, progressive and multicultural.

Much of the angst during the latter part of 1919 centered around the “Wartime Prohibition Act,” a law that pretended the U.S. was still fighting WWI although the war had been over for a while. The real intent of the Act was to impose bone-dry prohibition upon America months before the real 18th Amendment Prohibition took effect, but there were legal questions raised and the Justice Department said the government (probably) wouldn’t enforce it, leading to patchwork compliance.

Saloons in Petaluma and Healdsburg closed, but many in Santa Rosa remained open pending a court decision, the bars becoming de facto speakeasies: “In some saloons, it is said, you have to cock your left eyebrow and ask for ginger ale, while in others you ask for whisky and get it,” reported the Press Democrat.

“City and county officials seem to have adopted a policy of hands off,” noted the PD, but all that ended shortly before Hallowe’en, after President Woodrow Wilson tried to kill the Wartime Prohibition Act and failed (see part II). Santa Rosa went dry, although some saloons stayed open to serve soft drinks – perhaps with something extra for the left eyebrow crowd – in the hopes that the courts would rule the Act unconstitutional, allowing America to have one last “wet Christmas” before full-fledged Prohibition kicked in. Sorry, the Supreme Court finally said in mid-December; the Act was valid law. Hearing that news left millions of Americans crying in their beer – or would have, if there were any suds to be had.

Over the following weeks, newspapers ran stories about their local taverns shutting down or evolving into some other kind of business. Reporters marveled that famous bars with their polished brass foot rails were sold for the wood and metal; the back bars, with their ornate carvings and etched mirrors which had reflected generations of men arguing politics and fast horses were taken apart and went for cheap. From the PD:

Santa Rosa saloon sites will be occupied by restaurants, candy factories and candy stores, and even by real estate offices…In only a few cases are saloon owners hanging onto their leases of Santa Rosa property, with any idea that they might be able to return to business. “It’s all over, so why worry about coming back,” declared one former saloon proprietor…About half of the old saloon sites are already wiped off the map. More are in process of change, and of the few remaining open as cigar stores and soft drink emporiums… |

While the barkeeps and the drinking public were made miserable by Prohibition’s approach, the grape growers seemed to wobble between denial and panic.

Just as the saloon crowd hung on to an unrealistic optimism that Prohibition would include an exemption for beer (see part II), many growers couldn’t imagine their lovingly tendered vineyards might become worthless overnight. The editor of the California Grape Grower newsletter found “during the last weeks of August, the writer visited practically every grape district in the State in an effort arouse the growers to an understanding of the critical situation. He was amazed to find them making absolutely no preparations for the disposal of their crop in the case the wineries were not permitted to operate.” Louis J. Foppiano later said in an interview they thought Prohibition “might last a few months, if ever, and then things would get back to normal.”1

The Sonoma County Grape Growers’ Association was only slightly more realistic. Faced with the choice of crushing the 1919 vintage or letting the grapes rot on the vine, they recommended proceeding with the harvest and holding the crush in reserve until the prohibition question is finally solved [emphasis mine].

But trusted authorities were telling them to get out of the wine grape business – NOW. Even 72 year-old Charles Wetmore, who had devoted most of his life to building the California wine industry, said any growers who did not have a contract for their grapes “should lose no time in converting all the space they can into young orchards.” The PD reported “all over the county the vineyards are being stripped of their grapes, and in many cases the pickers are being closely followed by other crews, tearing out their vines in anticipation of this being the last crop that will ever be harvested in the county.”

The advice from the Department of Agriculture was that Sonoma and Napa growers should switch to raisins – even though it was pointed out that wine grapes do not make good raisins because A) they have seeds, B) are not sweet, and since we have a shorter growing season than places in the Central Valley C) the raisins would rot on the vines instead of shriveling. The government’s response was that growers could replant all the vineyards – or, since there was a market for subpremium U.S. Grade B raisins, maybe we should be happy to settle for becoming a second-class version of Fresno.

From the State Board of Viticultural Commissioners came wails of lamentation, that Prohibition would “seal the doom” for an entire agricultural industry unless the Amendment was overturned, as wine grapes could only be used to make fresh wine. Don’t even try turning it into grape syrup or unfermented grape juice, they warned, “because there is no rational assurance that such products could be successfully marketed.”

Let’s hit pause for a moment to consider the scope of all this. Saloons could be repurposed into restaurants; instead of selling to breweries and distillers, grain farmers could sell to flour mills and make the same money. But wineries couldn’t be turned into ice cream parlors, and it would take years for any “young orchard” to bear a fruit crop. Hops, a major Sonoma county crop unaffected by Prohibition, was out of the question because the plants needed a plentiful water supply. Thus the United States government was about to wreck the economy of Northern California – and for no reason other than pleasing the moral ideals of some. Hardest hit would be Sonoma county, where the wine business brought in $4 million/year.2 Put another way: It would be like the government today forcing the county to lose about a billion dollars of its GDP over the next decade.

This was a serious issue which urgently needed a serious national debate – but instead of that, our ancestors received a condescending lecture. Since the real intent of prohibition was to bully the rest of country into obeying WASP cultural standards, it should come as no surprise that a self-righteous prig blamed Wine Country for being the cause its own problems.

“The Wine-Grape Riddle” was a lengthy essay which appeared in Country Gentleman, the most popular magazine in rural America. It accurately quoted the red flag warnings from state Board re: no use for the grapes other than making wine, most of the vineyard land being unable to support any other kind of farming, plus nothing would be as profitable as wine grapes. Mostly, however, the editorial writer makes sneering remarks about the North Bay having a remarkable number of idiots. “The combined intelligence of all the purveyors and manufacturers of intoxicants who ever lived wouldn’t furnish the average pullet with sense to cross the street safely.”

According to the author we demonstrated our collective stupidity by voting for prohibition, thus acting against our own best interests. That was a remarkably ignorant thing to write; the previous year Californians had voted against pro-prohibition ballot items, and by overwhelming numbers in Wine Country (see part II). And, of course, voters never had a direct say in its passage – amendments to the Constitution are ratified by the state legislature.

But that was just the editor’s starting premise; he claimed 42 percent of Sonoma county farmers were foreign born, further presuming most never bothered becoming citizens so they could vote – which was because they were Italians and too simple-minded to understand what prohibition meant. Yes, Gentle Reader, on the eve of a multi-million dollar agricultural crisis, the largest chunk of (what was almost certainly) the most widely read information about the situation was at its core an assortment of ugly stereotypes and ethnic slurs, believe it or not.

Our ancestors must have been crestfallen when that magazine arrived in their mailboxes; the start of Prohibition was still a month away and here was their obituary already written, their livelihoods sent off with a caustic goodbye and good riddance. The Press Democrat fired back with a response from state Board member Charles E. Bundschu and although the letter (transcribed below) could have been stronger in its defense of Italians, it otherwise countered most of the points in the article.

And then the day of Prohibition arrived: January 17, 1920. But instead of the sky falling, something very good and very unexpected happened. Three good things, actually.

Just days after Prohibition officially began, vineyardists found buyers hammering down their doors, offering $25/ton for their 1920 wine grape crop in the autumn. Everyone appeared taken off guard; not only were their grapes still in demand, but that was a premium price. The Press Democrat remarked, “the grape growers of Sonoma county cannot complain of National Prohibition as the price is paid to be more than per ton higher than the average price paid for grapes during the past ten years.” A few days later, that offer was already too low.

As winter turned into spring, the contract price kept climbing: $30 per ton; $40; “Growers Are Refusing $50 Ton for Grapes,” was the PD headline on April 1, which might have seemed like an April Fool’s Day joke, had it been predicted just a couple of months earlier. By early May it was up to $65, and a year later, it would be nearly twice that. The growers who had taken a gamble and not ripped out their vines had now hit the jackpot.

What was going on?

It seems that it was foolish to presume people were going to obey the new law. Even before Prohibition home winemaking was popular (and yes, it was mainly done in Italian households). At end of 1919 at least 30,000 households in Northern California and Nevada were making home wine but they were buying just a fraction of the wine grape crop sold to consumers; most of it was shipped East via refrigerated freight cars. And once Prohibition began and there was no other way to obtain wine, demand for the wine grapes skyrocketed 68 percent over the previous year.3

All of this was legal. There was no restriction in the Volstead Act on growing wine grapes, selling them to a broker who would transport the produce somewhere else in the country where they would be purchased by a consumer in, say, New York City. Sure, it was now against the law for the buyer to allow those grapes to ferment an alcohol content higher than 0.5 (ABW) but hey, who’s to know?

When the Act was made law just a few months before Prohibition, the culture warriors believed it would be tweaked to fix any shortcomings, presumably making it even MORE restrictive. That Country Gentleman article suggested it might be modified to block transport of wine grapes or make it “too dangerous for the householder to manufacture his own wine,” which sounds uncomfortably like tossing out the Fourth Amendment blocks on searches and seizures.

But after having experienced a couple months of “bone dry” Prohibition, public sentiment was starting to shift in the other direction. New Jersey and Wisconsin defied Volstead and authorized sale of light beer. More newspapers began editorializing against Prohibition calling for a national referendum or immediate repeal. With 1920 being a major election year, the Democratic party – still torn between Wet and Dry factions – added a “moist” plank to the party platform which reflected President Wilson’s views that exceptions be made for wine and light beer. (The resolution also cited concerns about “vexatious invasion of the privacy of the home” which suggests people were worried about raids, whether the threat was real or no.)

On July 24 the Internal Revenue Bureau ruled homemade wine and cider could have more than 0.5 percent alcohol as long as it was consumed at home and “non-intoxicating.” Home wine making was now legal, as long as you didn’t make over 200 gallons/year – the equivalent of about 1,000 750ml bottles.

On July 24 the Internal Revenue Bureau ruled homemade wine and cider could have more than 0.5 percent alcohol as long as it was consumed at home and “non-intoxicating.” Home wine making was now legal, as long as you didn’t make over 200 gallons/year – the equivalent of about 1,000 750ml bottles.

That was the second bit of good news for our grape growers during the early months of Prohibition. The third was the rapid development of commercial dehydrators.

Shipping fresh grapes across the country was always a chancy proposition; the railcars could be delayed because of labor issues, routing problems, overcrowded delivery terminals or a host of other reasons. Growers assumed the entire risk of transportation; if the fruit was spoiled by the time it reached the buyer, they were liable for shipping costs. Among the horror stories was that of a small Alexander Valley vineyard that shipped twelve tons of grapes to New York only to receive a 17¢ check. 4

Those risks were reduced significantly if dried grapes could be shipped instead. UC/Davis had been working on perfecting the best formula since the summer of 1919, with the goal of not drying them to the point of becoming raisins but rather to evaporate away the water content, keeping the grape’s color and flavor once it was rehydrated. Charles Bundschu’s letter in the PD mentioned the importance of this; in fact, he predicted everything that would happen in early 1920:

…The demand for dried Wine grapes is so great since Prohibition has become effective that California will not be able to supply the demand. To bring up a very important point, the very same grapes that were formerly used for the legitimate business, are now being dried and sold in small quantities to people who are making their own wines. It is encouraging an illegal business and I would ask whether under these conditions it is better to conduct a business along legitimate lines or whether it is better to force people to violate the laws?… |

Read the California Grape Grower newsletter from those months and marvel at how quickly the gloom and despair turned into bullish optimism. Even though the dryers were not cheap and were the size of a two-bedroom bungalow, wineries and investors were gung-ho on building them; a Chicago brokerage spent $35,000 on one at West Eighth street in Santa Rosa. By the 1920 harvest, there were seven dryers in Sonoma and three in Napa county, including Beringer and Gundlach Bundschu.

I’ll wrap up this particular article on that high note from the summer of 1920, as the topic of this series was just the advent of Prohibition. Although I’ll certainly write about our bootlegging days later, for more of what happened locally in the vineyards beyond this point see Vivienne Sosnowski’s book, listed with other reading materials below. But in my prowlings I stumbled across an intriguing rabbit hole that no one has researched (as far as I can tell) and I’m hoping this coda might tempt some other historian to dig deeper into the story of “Vino Sano.”

I’ll wrap up this particular article on that high note from the summer of 1920, as the topic of this series was just the advent of Prohibition. Although I’ll certainly write about our bootlegging days later, for more of what happened locally in the vineyards beyond this point see Vivienne Sosnowski’s book, listed with other reading materials below. But in my prowlings I stumbled across an intriguing rabbit hole that no one has researched (as far as I can tell) and I’m hoping this coda might tempt some other historian to dig deeper into the story of “Vino Sano.”

Although the future of dried wine grapes seemed bright, the demand for them hit the skids after the government sanctioned home winemaking that July, which was followed by ultra-cheap European dried varietals flooding the East Coast markets. Also, the fresh grape shipping situation improved dramatically every year; the railroads kept adding hundreds more refrigerated cars annually and as the war faded in the distance, there was far less scheduling chaos caused by the military commandeering the tracks. By the 1921 harvest there was little interest in drying wine grapes, or at least selling them on the open market – there might have been private contracts. It became a niche market, like making sacramental and kosher wines (legal under Prohibition, but only under special license).

Then in August, 1921, this little ad began appearing in Midwestern and Eastern newspapers:

That San Francisco address belonged to Karl Offer. He was (supposedly) a former German aviator who was awarded an Iron Cross for valor in the 1914 Siege of Tsingtao, settling in San Diego the following year and where he became a dealer in fine German jewelry. After the U.S. entered WWI he was arrested as a German agitator/alleged spy and sent to Ft. Douglas in Utah for the duration of the war. When Offer surfaced in San Francisco during early 1921 he was now a bond trader (particularly German bond futures) and currency speculator (German marks and Russian roubles) running large ads in newspaper business sections.

Most of Offer’s “kick in a brick” ads were in the help-wanted sections as he was seeking salesmen and distributors; his own product ads stopped the next year as Vino Sano dealers began their own regional advertising, followed by him opening storefronts in San Francisco and New York City (and possibly elsewhere). The ads and the package itself included a clever gimmick, warning customers there was a risk the reconstituted juice from the brick could ferment and become alcoholic.

That grape brick concept was simply an act of genius. Fresh wine grapes were only available for a few days in the autumn and you had to have connections to get them, particularly outside of the Bay Area. The bricks were shelf-stable and could be ordered through a grocery store or pharmacy. The markup was also astronomical; as a rule of thumb three pounds of fresh grapes made one gallon of wine, and the wholesale price of dried grapes was 10¢ a pound. Vino Sano agents sold those bricks for up to $2.50 per.

Offer was charged twice for violating the Volstead Act, in 1924 and 1927 and in both cases was acquitted by juries. Let it be noted, however, that he was found guilty of something worse – in 1925 he was charged with misleading investors and lost his bond trading license. In 1942 he was again suspected of being too pro-German and ordered to leave the West Coast as a potential security threat.

I would very much like a researcher to discover where he obtained the dried grapes that his San Francisco factory pressed into bricks. The only article on grape bricks suggests they came from the Beringer winery but that article contains factual errors, among them claiming the bricks were made of “concentrated grape juice” while news coverage during the jury trials clearly stated they were “compressed grapes.”

The big question I hope someone can answer is this: How successful was Vino Sano? Did they manufacture 10,000 bricks? 100,000? A million? More? Sure, the finished product was probably not very good wine unless the home winemaker was very lucky, but more relevant is that their degree of success could be a unique bellwether to what was happening nationwide. I imagine selling a consumer-friendly wine-making kit tapped perfectly into the zeitgeist of the time, with the public growing more rebellious against Prohibition with every passing year.

Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition by Daniel Okrent, 2010. Very readable and a good companion to the Sosnowski book.

Prohibition: The Era of Excess by Andrew Sinclair, 1962. By far the most thorough book on Prohibition and national events leading to it.

California Grape Grower (newsletter); December 1919 – December 1921. Highly technical articles but worth reviewing for the editorials, harvest reports and ads, plus many anecdotes.

Prohibition as a Democratic Issue (article); Literary Digest, March 20, 1920. The surprisingly vigorous pushback during the early days of Prohibition.

1 When the Rivers Ran Red: An Amazing Story of Courage and Triumph in America’s Wine Country by Vivienne Sosnowski, 2009 |

2 Statement from the Sonoma County Farm Bureau to President Wilson mentioned in part II: “PRESIDENT TOLD OF VINE AND HOP INDUSTRY HERE”, Press Democrat, August 8 1918 |

3 The 1919 crop was 128,000 tons and the 1920 estimate was 215,000 tons. The 1921 estimate was 250,000 tons with Sonoma county being the largest producer, despite much of the Northern California crop being lost to a late frost. Household statistics based on those who declared they were making wine under the Wartime Prohibition Act and paid the 16 cents/gallon tax. |

4 Sosnowski op. cit. pg. 80 |

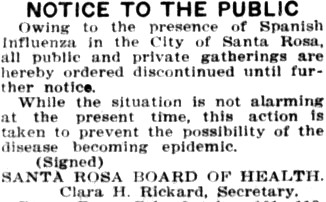

Santa Rosa May Be Dry, But Some Have Their Doubts

Is Santa Rosa dry?

The law says it is, but there are some doubters.

Rumor has it that despite the war-time prohibition on ail forms of liquors, whisky is being sold openly at several saloons.

Of course, the question of the legality of 2.75 per cent beer ia being threshed out in the courts and it is openly acknowledged by the saloonmen and city authorities that beer containing that percentage of alcohol can be obtained in any saloon. The city has even licensed dealers to sell this beer, pending federal decision.

But the hard stuff — the distilled spirit of the rye and corn — whisky, which was supposed to have been everlastingly knocked out by the war-time prohibition solar plexus blow, rumor declares is still on a more or less open sale.

In some saloons, it is said, you have to cock your left eyebrow and ask for ginger ale, while in others you ask for whisky and get it.

Rumor also says that one Fourth street saloonman is in more or less of a defiant mood, and has openly issued a defi [sic] to federal officials, declaring he will sell to whoever asks for it, and make a test battle in the courts.

City and county officials seem to have adopted a policy of hands off, in view of the fact that selling of intoxicating liquor is a federal offense, and thus far no federal officers have gotten as far as Santa Rosa in their raids on whisky-selling saloons. Several arrests, however, have been made in San Francisco.

It is pointed out by those interested in suppressing the sale of whisky, that the city has issued no licenses for the sale of this brand of fire-water, and the saloons are operating under another form of license, designed for 2.75 per cent beer.

– Press Democrat, October 2 1919

MAJORITY OF GRAPE MEN ARE CRUSHING THEIR CROP

Precedent Set by Leaders Following Decision of Association Is Being Generally Followed Under Conviction That It Is the Only Procedure Possible to Save Any Part of the Crop.The majority of the grape growers in Sonoma county are crushing the 1919 vintage, when unable to sell, and some are doing so who could have sold, according to a prominent grape man’s statement here last night.

The growers generally are crushing, considering it the best, and in fact the only possible precedent to follow, this man said, especially in view of the decision of the Sonoma County Grape Growers’ Association that this year’s crop would be crushed and held in reserve until the prohibition question is finally solved.

Most of the wine, in fact all that has been crushed to date, has been made for sacramental purposes, it is said.

With the grape crop coming on rapidly, forcing the necessity of harvesting the grapes, or allowing them to rot on the vines, the growers have feverishly gone ahead to save all possible of their crop by making it into wine, which will not be put on the market or offered for use in any way, until all the fine legal points are established.

All over the county the vineyards are being stripped of their grapes, and in many cases the pickers are being closely followed by other crews, tearing out their vines in anticipation of this being the last crop that will ever be harvested in the county. Those taking out their vines are already laying plans for experimenting with something else, hoping that they will not entirely lose out by prohibition.

– Press Democrat, October 8 1919

BOOZE OF ALL VARIETIES NOW BANNED HERE

Booze of all kinds was absolutely non-procurable in Santa Rosa Wednesday night, due to the passage by Congress of the dry enforcement act over the presidential veto.

Even the lowly 2.75 per cent beer, hitherto on sale in every saloon, was not obtainable.

“No. we have no beer, but we have some very nice soda water,” was the answer made in half a dozen saloons which were open Wednesday. All the other liquor emporiums were as dark as the the outlook of their proprietors.

Some of the saloon proprietors are keeping open, selling soft drinks, to be on the job when war time prohibition is declared off by the signing of the peace treaty. Others who have closed say they will reopen when the saie of liquor is again legal.

But the dry enforcement bill has accomplished one other thing in addition to drying up Santa Rosa — it has made a lot of converts for the early signing of the peace treaty.

– Press Democrat, October 30 1919

Liquor Licenses Are Refused by the City

Despite the fact that several saloon men have applied for liquor licenses the city authorities under the present federal laws have refused to issue any license for the sale of liquor. Most of the saloons in Santa Rosa have been closed, as they have throughout the state, but in a few cases the proprietors, in an effort to retain any possible advantage in case wartime prohibition is annulled before national prohibition goes into effect, have kept their places open and cater to the soft drink trade, although they are said be losing money by doing so.

– Press Democrat, November 5 1919

ENFORCEMENT LAW AND BEER ALCOHOLIC CONTENT DECISIONS NEXT MONDAY

By the Associated Press.WASHINGTON, Dec. 15.—By unanimous decision, the legality of the war-time prohibition act was upheld today by the supreme court. The decision was written by Justice Brandeis and held in effect, however, that the war-invoked “dry” law may be revoked by presidential proclamation of neutralization.

Giving his opinion that the court, however, would not add its opinion regarding the constitutionality of the prohibition enforcement act or on appeal regarding the alcoholic content of beer, leaving those cases to future opinion, which may be handed down next Monday, before the court recesses for the Christmas holidays to January 5.

This decision practically swept away all hopes of a wet Christmas, as the chance of the war-time act being repealed before prohibition takes effect one month from tomorrow was considered remote.

PENALTY ACT IN DOUBT

Upon the court’s decision on the prohibition enforcement law will depend whether the federal government has at hand any legal means for making tho amendment effective.

The constitutionality of wartime prohibition. however, the drys are confident, will keep tho country dry until the amendment is carried into effect by law of its own.

In deciding the question the Supreme Court also dissolved injunctions restraining revenue officials from interfering with the removal from bond of about 70,000,000 gallons of whisky valued at approximately $75,000,000, held by the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company of Louisville. Ky.

WAR POWER STILL IN USE

The signing of the armistice did not abrogate the war power of Congress, Associate Justice Brandeis said in reading the decision of the court.

Justice Brandeis said the government did not appropriate the liquor by stopping its domestic sale, as the way was left open for exporting it.

Justice Brandeis also called attention to the continued control of the railroads and reassumption of powers by the government relative to coal and sugar under war acts to show that the government continues to exercise various war powers, despite the signing of the armistice.

The constitutional prohibition amendment is binding on the federal government as well as the states, and supersedes state laws, the court declared.

– Press Democrat, December 16 1919

THE WINE GRAPE RIDDLE BRINGS OUT MANY POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

The publishers of the Country Gentleman recently sent Mr. Jason Field, one of their traveling editors, into this section to investigate and write up the present standing of the wine grape industry, and his report has no doubt been read with much interest by their numerous subscribers in this territory, some of whom do not quite agree with him in the results of his findings.

After carefully studying and reviewing the whole situation Mr. Field disposes of the “Riddle” in the following illogical summary:

1. Beverages containing alcohol – which includes wine – cannot be manufactured or sold any more; and

2. Therefore, the wineries will not run and the wine-grape growers must go out of business; but

3. It has not yet been declared illegal to transport either wine grapes in the fresh state, or wine-grape raisins for wine making purposes: and

4. Thousands of tons of grapes and raisins are being sold and shipped to individuals who will make wine of them: and also

5. It may not be illegal for a man to crush grapes in his own house for his own use, even though the juice does ferment; and

6. As it will probably ferment before he drinks it, he may be a violator of the law; but

7. As yet no one seems to be in a position to say that he will even then be interfered with, unless

8. He soaks up a skinfull of the liquor too hastily and then goes out and gets arrested; whereupon

9. It will be asked where he got the intoxicating liquor, and the manufacturer – even himself – can be and will be imprisoned: and meanwhile,

10. What in the name of Sam Hill will he do with his vineyard — root it up and go out of business, or just paddle along and take his chances?

This logic is quite beyond the innocent Italian in Sonoma County, and he is getting wild-eyed trying to understand it.

Mr. Field then concludes his investigations with the following hint of a solution:

It is the little vinyarists [sic] who are hardest hit, naturally. The big holders have capital enough to hold out for a long lime; to go into other lines; to seize shipping opportunities.

The big ones are “hollering” the loudest, and making the most money out of their grapes this year. The little chap who has, because the land was so cheap, jerked his vineyard rigid out of the sage-brush, at the front door of Coyoteville is the one who will go in the wall.

Suppose that the prohibition law is so rigidly enforced as to make it dangerous for the householder to manufacture his own wine, either from fresh wine grapes or dried grapes — thus cutting off all markets for the wine making purposes?

At first glance this appears an unreasonable supposition. Human nature being what it is, and the transition from grape juice to wine being a natural one, it would seem that illicit wine would always be with us. But it is possible for the enforcement officers to make it so difficult to transport the makings that the wine-grape growers could no longer profitably count on that outlet. What then?

There are several possible “outs” for the wine-grape grower with established vines. Few new plantings would be made on such obscure and doubtful chances. They are:

1. Drying by sun and evaporators for use as raisins. We have seen that most wine grapes would not make good raisins. Some would make raisins of fair quality. But this market is not promising.

2. Grape syrups. There is at present no market developed for grape sirups [sic]. It is doubtful if a market could be created in time to do the growers any good. The sirups would have to bring a much larger price than ordinary sirups.

3. Grape juice. Under this head something is going to be done. The market for grape juice has grown by leaps and bounds in the past several years, and the Eastern manufacturers of grape juice foresee a vast demand which Concord vineyardists of the East cannot supply. This is said to be the explanation of the sale of vineyards and wineries to the so-called Virginia Produce Company. I am told that the head of this company is a well-known grape-juice manufacturer.

At present the unfortunate part of it is looked at agriculturally, that the wine-grape growers are in the position of one who is doing something under the blanket instead of in the open. It is not wrong to raise grapes; it is not wrong to send grapes to somebody else; but if wine is made and someone becomes intoxicated, then the finger begins to swing around to the man who raised the grapes.

Subjoined is a copy of an answer to Mr. Field’s version of the “Riddle” which was sent in by our townsman, Mr. C. E. Bundschu.

The Editor.

Country Gentleman,

Philadelphia. Pa.Dear Sir: —

The articles on the “Wine Grape Riddle” by Jason Field published in your issue of November 15th and 29th have been read with a great deal of interest and I wish to compliment Mr. Field on the data that he has gathered covering this question, but the article is written from a probition [sic] and I therefore am taking the liberty of giving you the other side of the question:

First let us refer to the article in which he writes about the sweet wine industry, which centers in through San Joaquin Valley. It is quite true that in the face of Prohibition legislature, properties have changed hands at unheard of prices; there are two reasons for this: If Mr. Field had only extended his investigation a little farther he would have found out that land values in California have greatly increased since the war, there is a boom at the present time in country lands and prospective buyers are therefore paying exhorbitant prices on land purchases. There is no boom in the sweet wine industry as the manufacture of sweet wine, except non-beverages and medical purposes, is prohibited.

Furthermore the districts where sweet wines were produced are especially well adapted for raisin grapes and the demand for raisins has been an great that prices have advanced from 3 and 4 cents to 13 and 14 cents per pound, and this naturally would be an incentive to purchase vineyards for raisin purposes; a great part or all sweet wine grapes are particularly well adapted for raisins. The Wine grapes that are grown in this section are also easily dried in the sun, which is a very inexpensive process; it is not necessary to put up any dryer or dehydrator. The demand for dried Wine grapes is so great since Prohibition has become effective that California will not be able to supply the demand. To bring up a very important point, the very same grapes that were formerly used for the legitimate business, are now being dried and sold in small quantities to people who are making their own wines. It is encouraging an illegal business and I would ask whether under these conditions it is better to conduct a business along legitimate lines or whether it is better to force people to violate the laws? I say force, because I believe a man is entitled, according to the constitution of this country, to enjoy his glass of wine or glass of beer, the same as any other food, which he has been in the habit of using. Wine is a food, which he has been in the habit of using [sic]. Wine is a food and a temperance drink. There are many foods which are more injurious than wine.

I would also like to enlighten Mr. Field, why Fresno county, which is one of the largest grape producing counties in this State voted “dry.” It is not entirely due to the prices fixed by the California Wine Association, but we have in this State what we call local option, and people in the Fresno district voted dry in order to do away with the road house and the saloon; there was no other alternative, but to either vote the district bone dry, or allow the road house and saloon; and therefore you can readily understand why this section voted dry. The Wines produced in this section are not consumed there, but shipped out, in fact we might say 90 per cent of the wines produced in the State of California are shipped to the Eastern markets.

Referring to the second article on the dry wine districts, Mr. Field admits that a great injustice is done to the Grape grower who was encouraged in the planting of grapes by the United States Government, as well as by our State. The United States Department of Agriculture is still maintaining experimental plots throughout this State and the Government is appropriating funds for the maintenance of these experimental vineyards. On the one hand the Government prohibits the manufacture and sale and on the other hand the Government is leasing land for the sole purpose of demonstrating to the farmer what grapes are best adapted for his particular soil.

I would like to correct an impression, however, that Mr. Field gives, that the Italian dominates the Dry Wine Districts. This is not so; it is true that the Italian is generally employed in wineries and vineyards, but from any ownership stand-point the vineyards in this part of the State are owned by Americans, that is to say generally of foreign extraction, there are French, Swiss, German and Italian. We might say the largest portion is in the favor of French and German-Americans. The pioneers of this industry planted their vineyards in the late 50’s and early 60’s, some of these estates have been handed down to the next generation and some of them are still farmed by the original settler.

It is easy enough to make the statement that the grapes can be uprooted and other crops planted, but this is easier said than done. I would like to point out an instance, and I can mention many more, that are in the same class. A man that has spent a lifetime in setting out a vineyard, perfecting his winery and settled down with a family, now in his declining years is asked to root up the vineyard and plant other crops. A man that has made a specialty of wine grapes is not familiar with other crops and the time that it would take to replant and get returns would be at least from six to seven years, in the meantime. who is to support the family and how is a man able to finance such a change? Then again it is a question of whether the soil will produce other crops. Seventy-five per cent of the vineyards grown in the dry wine districts are grown on land which will produee no other crops, so as to give a man fair returns on his investment.

Mr. Field also mentions in his article that the State of California voted dry. This is not correct, as this State voted wet with a large majority every time this question has come up in the State, but when our State Legislature convened. strange to say the legislature endosed “National Prohibition.” If there is any “Riddles” to be solved I would like to ask Mr. Field this: “Why did our State Legislature vote ‘Dry’ when our State voted ‘wet’”? Exactly what has happened in our State is happening throughout the entire United States. And it is unfortunate that an industry representing our investment of over 150,000,000 dollars in this State alone, should be used as a political football.

Feeling that some of your readers would like to hear from the grape growers view point, I remain

Yours very sincerely.

C. E. Bundschu.– Press Democrat, December 24 1919

Wine Company Bids $40 Ton for Grapes

SEBASTOPOL – The California Wine Association offered $40 per ton for grapes that crushed into 217,000 gallons of wine in the Sebastopol winery, according to General Manager F. P. Kelly…Wine men consider that this offer shows conclusively that the entire crush will be sold.

– Press Democrat, December 27 1919

One million dollars’ worth of wine, said to be the largest single shipment of wine ever made from California, left San Francisco for the Orient last Saturday. Included in the shipment will be 10,000 cases of the Golden State, extra dry, champagne, made at the California Wine Association’s big winery at Asti. Besides the champagne there will be 10,000 barrels of other wines. The wine went out on the Robert Dollar and will include some of the choicest wines ever produced in California.

– Sotoyome Scimitar, January 2 1920

Must Have Licenses To Sell Near Beer

Saloon proprietors and restaurant owners who sell liquor containing one-half of 1 per cent alcohol will be required to secure a liquor license, according to a statement yesterday made by Commissioner of Public Health and Safety G. C. Simmons at the meeting of the city commission.

Simmons asked that the city collector furnish him a list of all dealers who have not secured their licenses for the first quarter of the year. The city ordinance regulating the liquor traffic provides that a license must be secured for the serving of any intoxicating liquors, even to malt liquors of whatsoever nature.

– Sacramento Union, January 3 1920

COURT RULES 2.75 BEER IS ILLEGAL BREW

In Two Decisions Last Hopes Of Wets Are Swept Aside: Four Justices In Dissent

Anti – Saloon League Leader Calls Ruling “Sweeping Victory” For ProhibitionWASHINGTON—By a margin of one vote, the Supreme Court upheld today the right of Congress to define intoxicating liquors insofar as applied to war time prohibition.

In a 5 to 4 opinion rendered by Associate Justice Brandeis, the Supreme Court sustained the constitutionality of provisions in the Volstead prohibition act prohibiting the manufacture of beverages containing 1/2 of one per cent or more of alcohol. Associate Justices Day, Van DeVanter, McReynolds, and Clark dissenting.

Validity of the Federal prohibition constitutional amendment and of portions of the Volstead act affecting its enforcement were not involved in the proceedings, but the opinion was regarded as so sweeping as to leave little hope among “wet” adherents. Wayne B. Wheeler, general counsel for the Anti-Saloon League of America, hailed it as a “sweeping victory” and in a statement tonight said the only question left open by the court now is whether the eighteenth amendment is of a nature that can be considered as a Federal amendment and whether it was properly adopted.

– Chico Record, January 6 1920

HOP PRICES ASSURED FOR NEXT THREE YEARS

WOODLAND—That the present hop prices will be maintained for some time despite prohibition is the conclusion of a number of Yolo growers, Anson Casselman, a local rancher, has filed a contract with Le Pierce, county Recorder, for the sale of 120,000 pounds of hops to Strauss and Company of London England…

– Press Democrat, January 15 1920

Saloons Are Fast Disappearing Here

They said it couldn’t be done, but it was done, and the evidences of the passing of the saloon and hard liquor are multiplying in Santa Rosa and other cities of the land every day.

Not only have the saloons passed into history, with the amendment to the federal constitution, but even the places where the saloons were located are passing into the hands of other businesses, in no way related to the former trade.

Santa Rosa saloon sites will be occupied by restaurants, candy factories and candy stores, and even by real estate offices, according to facts learned Wednesday in a canvass of the city.

In only a few cases are saloon owners hanging onto their leases of Santa Rosa property, with any idea that they might be able to return to business.

“It’s all over, so why worry about coming back,” declared one former saloon proprietor. “I, for one, am going to look around and get into something else.”

“Why hurry?” was the query on the other hand from another saloonman. “I’m going to stay open, sell whatever I can sell, and see what happens. I won’t starve for several months even if I don’t pay expenses.”

A hurried survey of the situation Wednesday showed something like this has happened and is going to happen to saloons in Santa Rosa:

Jake Luppold’a famous “Senate” saloon in Main street is closed. Jake says his plans are unsettled, but he does not think the saloon business will ever come back.

Scotty Tickner has opened a restaurant in his former “Recall” saloon in Fourth street.

Across the street Hans Alapt has likewise changed the Eagle Bar into a restaurant.

The Rose Bar, next to the Rose Theater, has become the realty office of Garrett Kidd and Elmer Crowell.

The Grapevine, Mendocino avenue’s only saloon in recent years, will be remodeled into a restaurant for George R. Edwards, whose Lunchery will then move across the street.

The Brandel wholesale and retail liquor store in Fourth street is to open about February 1 as a grocery under the conduct of McCarcy & Woods.

Bouk’s candy factory is already established in the quarters in Fifth street formerly occupied by the Brown & son liquor store.

Bacigalupi & Son, grocers, have already absorbed the site at Fourth and Davis street, once occupied by a saloon.

A fruit and poultry market occupies the old Magnolia site at the corner of Fourth and Washington streets.

Fire wiped out of memory the States formerly the Germania, hotel and bar, near the Northwestern station.

And so the story goes. About half of the old saloon sites are already wiped off the map. More are in process of change, and of the few remaining open as cigar stores and soft drink emporiums, like Thomas Gemetti in Third street, their plans are unsettled.

Landlords are delighted with the manner in which the old saloon sites are filling up, and tenants are glad to be able to secure desirable locations.

– Press Democrat, January 22 1920

BUYERS ARE IN THE FIELD OFFERING $25 FOR GRAPES

Higher Prices Than Have Been Paid for Years Are Now Being Offered and Prompt Vineyardists to Trim Their Vines, Plow Their Land and Get Ready for 1920 Crop Despite “Dry” Era.

With buyers already in the field offering $25 per ton and boxes for handling the crop, the grape growers of Sonoma county cannot complain of National Prohibition as the price is paid to be more than per ton higher than the average price paid for grapes during the past ten years.

Several buyers are out seeking contracts for the 1920 black grape crop at $25 per ton with $5 cash advance on signing the contract and $20 on delivery of the grapes in the fall. With the exception of the last year, when somewhat higher prices contingent on the disposal of the wine prevailed, grapes have not averaged, it is said, $20 per ton in past years.

While it is said the present price is experimental and will be only for this year’s crop it is known that there is a movement afoot to stabilize prices of grapes at approximately that figure in the hopes of maintaining the land value in the county. If it works out at a conference to be held by big growers and firms seeking the grapes in the near future it will mean that the grape industry will become a fixed one similar to hops with one, two and three year contracts to the growers.

It is understood that the grapes are being purchased with the view of drying and shipping abroad. The price of shooks and freight rates will have a heavy bearing on the industry. It has been reported that the lines may require prepayment of all freights which would add a big item to the expense of handling the grapes in transcontinental shipment.

The prices for this year, at least, are not at all dark for grape growers with the price already fixed at $25 per ton and there will be few who will dig out their vines as long as contracts can be made at that price. Reports from various points in Sonoma county this week are to the effect that vineyardists are already trimming their vines, ploughing their land, and getting in readiness for the new crop. In some cases, however, growers are taking out the roots and putting in prunes and other trees, especially in the low lands and on good hill lands.

– Press Democrat, January 22 1920

John Peterson, wine manufacturer of Santa Rosa, has sold 143,000 gallons of wine for $74,000 to the California Wine Association. Price for a single gallon was 55c. The wine will be used for sacramental and non-beverage purposes.

– Petaluma Daily Morning Courier, May 4 1920

GRAPE MEN OFFERED SIXTY-FIVE DOLLARS

A number of vineyardists have this week been approached by buyers who have offered them from sixty to sixty-five dollars a ton for their coming crops of wine grapes. It is understood that some growers have accepted these prices, while others are disposed to hold and see the results when Grape Growers Exchange is organized. It is slated that permanent organization of the Exchange is likely to occur very soon, the time depending upon how quickly the required acreage of grapes is signed up in membership.

– Press Democrat, June 30 1920

DEHYDRATOR TO BE BUILT HERE, COSTS $35,000

International Brokerage Company of Chicago Buys Wine Association Site; Also to Build a Dryer in County.Santa Rosa is to have a new fruit dehydrator. to be built immediately by the International Brokerage company, said to be the largest handlers of California grapes in the United States.

The company, which has its main offices in Chicago. has purchased the California Wine Association’s site at West Eighth street and the N. W. P. railroad and will begin the construction of the first unit, a $35,000 building, immediately. The first unit will be used for grapes and all other classes of fruits…

The first unit will have a capacity of fifty tons, and further units will be built as fast as the tonnage warrants, it is announced, with a possibility of a total capacity of 500 tons every twelve hours.

The company contemplates» the construction of another dryer in the county for packing and distribution.

The local dehydrator will eventually handle all products grown in this part of the state, including vegetables, green fruits and dried products. Other dehydrators owned by the company are already being operated in the central part of the state. The plant will operate the year round and is expected to have a large payroll. All the products will bear the names of Santa Rosa and Sonoma county.

– Press Democrat, June 30 1920