Quiz: Name the woman in 1870s Santa Rosa who was a successful real estate investor. Answer: It’s a trick question (sorry!) because we don’t know her real name. Oh, and by the way: She was a former slave.

On her tombstone at Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery she is Elizabeth Potter. Legally she was C. E. Hudson, which was the only name on her will and how she bought and sold land – except for once when she identified herself as Charlotte E. Hudson. The 1860 census named her as Elizabeth Hudson, and her death notice in the local newspaper stated she was known as Lizzie Hudson. Whatever her name, Elizabeth/Charlotte Potter/Hudson was a remarkable woman. The reason you’ve never heard of her before is certainly because she was African-American and Santa Rosa’s 19th century Democrat paper had a single-minded determination to erase the presence of its black citizens, only mentioning them when there was a shot at grinding them down with ridicule.

(This is the second installment in the series, “THE HIDDEN LIVES OF BLACK SANTA ROSA.” It will be helpful to read the introduction for background.)

Most of what we know about her comes from her tombstone and mentions in her brother’s obituary (there was no obituary for her – she received only that two-line “Lizzie” death notice, which appeared for a single day). From real estate transactions we can guess her net worth was about $7,000 before she died in 1876; at that time in Sonoma County, $10k was the threshold for being considered wealthy.

Her birth name was almost certainly Elizabeth Potter and she was born a slave in Maryland, 1826. Bondage ended when she escaped a slaveholder in Virginia and somehow made her way to Santa Rosa, California. Speculate if you want that “Hudson” was related to a deceased husband, but note she never once used “Mrs.” with any form of her name, as was the custom at the time for widows.

We first meet her locally as Elizabeth Hudson in the 1860 census, where she is part of the household of civil rights activist John Richards, counted as a servant. (A servant was defined as a paid domestic worker.) She was listed as 37 years old and from Maryland. But a few days later, she was listed a second time as a servant for John H. Holman – but this time from Virginia. A double-count mistake like that is unusual, but not all that rare; the respondent for the household was almost certainly one of the Holmans and not Elizabeth herself.

RIGHT: The Potter family plot at Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery

RIGHT: The Potter family plot at Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery

After the Civil War she managed to reach her older brother who had remained in captivity until emancipation, having been sold four or five times in his fifty-odd years. At her urging, Edmund joined his sister here in 1872 and two years later, they became co-owners of 50+ acres north of town next to the county poor farm. Presumably all or most of the $1,200 price was contributed by Elizabeth (this land deal was the only time she used “Charlotte”).

There Edmund and his wife, Martha, made a small farm. Elizabeth may have lived with them as well; it was where she died in 1876.

Elizabeth knew she was dying and a few months prior sold one of her investment properties for the first time, getting $1,700 for a downtown parcel. She also tried to lure more of her family to Santa Rosa; in a poignant bequest in her will, she offered 1⁄3 of an even more valuable lot to “any cousin of mine who may come out from the East and attend me in my last sickness and may be here before my burial.” No one came. When she passed away just before Thanksgiving, her 59 year-old brother Edmund – who could read but not write – inherited everything.

Edmund and Martha’s sunset years looked secure. The parcel he inherited was at the foot of Fifth street (where the Post Office would be built decades later) and sold in 1879 for $3,100, which should have been enough for them to comfortably live on for the rest of their lives. The next year the Potter farm was valuated at $1,600, although they had made no improvements – it was still all meadowland. They had a pig and a couple of dozen chickens.

Tragedy struck as Martha died in a 1880 fire (she fell asleep while smoking) and the Democrat newspaper described her agonizing death in lurid detail. This was not at all unusual – the paper routinely spared no ink in describing how African-Americans died; in the following profile it was even reported the old man was found “partially undressed.” It was another routine exercise in racism, as deaths of white members of the community were almost never treated in such a demeaning manner. And it wasn’t limited to the 19th c. Democrat; the same treatment can be found in the Press Democrat as late as 1911.

RIGHT: Illustration from “City Cries: Or, a Peep at Scenes in Town” Philadelphia, 1850

RIGHT: Illustration from “City Cries: Or, a Peep at Scenes in Town” Philadelphia, 1850

What happened during the next few years is a mystery, but apparently he lost his farm and everything else. No legal notice of the property being sold can be found in any newspaper, nor was there any clue as to what happened to his sizable nest egg. He was next spotted in 1884, when the city paid a bill he submitted for $4.02. That likely meant he was now the whitewash man.

Whitewashing was among the lowest menial jobs traditionally held by 19th century African-Americans. It was messy work particularly as ceilings were often whitewashed but it was not dangerous – ignore internet claims that old-time whitewash contained lead – though there were several variations in the formulas (PDF).

He was now living in town at 528 First street and married again in 1890 to Louisa Hilton, a woman 25 years younger who had four daughters. The minister in the ceremony was Jacob Overton (see intro), one of the Bay Area civil rights activists who had earlier kept John Richards and others here in touch with the movement’s progress. There’s no evidence that Potter or his sister (under any of her names) were actively involved in the fight for equality, but it’s still noteworthy he had some sort of connection with a man as hooked-up as Overton.

Living in Santa Rosa proper exposed the Potters to the unquenched racial hatred that still burned here thirty years after the Civil War. In his collection of character sketches “Santa Rosans I Have Known,” Press Democrat editor Ernest Finley recalled being sent on an errand to ask Potter’s daughter for help with housework at his parent’s house. Finley didn’t know the neighborhood and asked Judge Pressley for directions. (Pressley was the Superior Court judge at the time and an outspoken racist, having infamously once said he came to Santa Rosa “to get away from the carpet-baggers, scalawags and ni***rs of South Carolina.”) Naturally, the judge used the boy’s simple question as an opportunity to throw in a racial slur:

One time while a small boy I was sent down to Uncle Potter’s house to notify the aforesaid daughter that her services would be required at our house the following morning. I had difficulty in finding the place, and as Judge Pressley lived in that neighborhood I rang his doorbell and when he appeared, made inquiry. I must have been somewhat embarrassed or confused, for I said, “Judge Pressley, is there a negro lady who lives somewhere near in this vicinity?” Judge Pressley, a southerner of the old school, replied somewhat testily, “There are no negro ladies living around here, but Uncle Potter’s house is just around the corner and I think you will find Mandy or her mother at home.” |

His “Uncle Potter” nickname probably emerged soon after he moved to Santa Rosa, and make no mistake, this was not a term of endearment or respect as “Tío” is used in Spanish-speaking cultures. In Jim Crow America, addressing an older African-American man as “uncle” was just the flip side of calling a younger adult “boy.”

As noted in the intro, racism in Santa Rosa’s Democrat newspaper during the later 19th century was usually passive – ignoring the existence of people like Elizabeth Potter and less often flinging around “n word” type slurs. Not so with Edmund Potter; the paper portrayed the 80 year-old man as the town’s laughable resident character.

“Uncle Potter” first appeared in the Democrat on April 13, 1895: “De trouble wid de ladders ob success in use now-er-days,” said Uncle Potter at his home on First street, “am dat they ain’ strong enough in de j’ints. When yoh gets pooty clos ter de top, dey’s liable ter break and drap yer.” Over the following 2½ years there would be dozens more of these aphorisms, metaphors and snarky quips about politicians, all written in pseudo-plantation patois – Gentle Reader may be justly skeptical that a literate man born in Maryland would speak like a Mississippi field hand. More examples:

“De man dat calls hisself a fool will nebbah forgive another for agree!n’ wid him.” “When yoo poke a toad philosophically you can’t tell which way he will jump nor how far, an’ its about the same way wid de avrage jury.” “Politicians am like corkscrews, de mo’ crooked dey am, de stronger their pull.” “De man ain’t been born dat kin live an’ love on bad cookin’. Good cookin’ keeps lub in de house much longer’n good looks.” “Political economy seems to me it’s a sickness kinder like the grip. It comes on with a weakness fer office, and you can’t get shet of it, no way. Bime by it brings on a third-term fit — that’s skeery, I tell you, and there ain’t no economy in that fer po’ folks who do the votin’, and there ain’t no economy for the other fellow, for he ginrally gets beat any way.”

The blame for this shameful “humor” falls entirely on Robert A. Thompson, brother of the paper’s founder and Confederate flag-waver, Thomas L. Thompson. Robert was editor and publisher of the Democrat in those final years before it was sold to Ernest Finley & Co. in 1897. He’s since been portrayed as a serious scholar for having written two important early histories of the county and town.*

What Robert was doing in the mid-1890s was just an updated version of what his brother did with racially-charged language a generation before – titillating the white supremacists in the paper’s audience. Readers would have recognized the “Uncle Potter” dialect and backwoods insights as being in step with the popular “Lime-Kiln Club” stories of the 1880s, several of which appeared in the Democrat and were collected in a 1882 top-selling book, “Brother Gardner’s Lime-kiln Club”. With foolish characters such as Pickles Smith, Boneless Parsons and Elder Dodo, the stories portray African-Americans as dimwitted and/or childlike, seeking (and failing) to mimic whites and white society. And, of course, watermelons were stolen. When teaching about the history of Jim Crow, the destructive impact of this white superiority crap in popular culture merits far more attention than it gets, in my opinion.

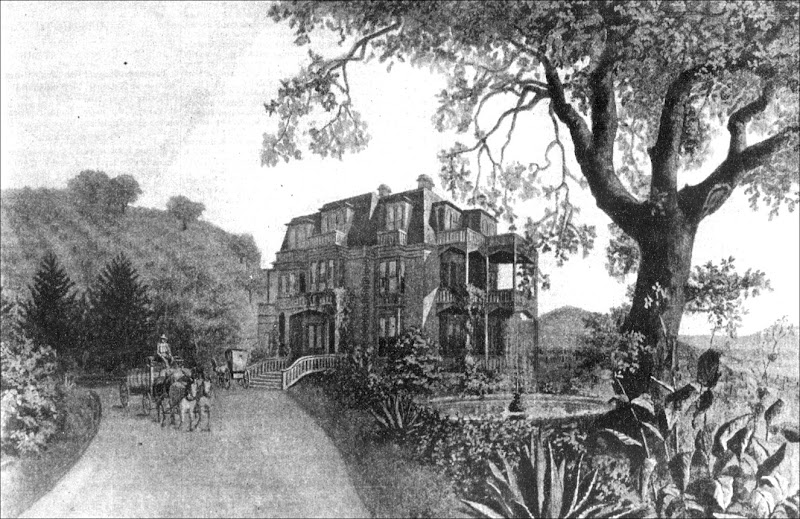

RIGHT: Drawing of Edmund Potter from the Sonoma Democrat, July 25 1896

RIGHT: Drawing of Edmund Potter from the Sonoma Democrat, July 25 1896

While the Lime-Kiln Club was fictional, “Uncle Potter” was not. Edmund Pendleton Potter was a very real, very elderly man trying to make a subsistence living to support himself and his stepdaughters – his second wife had died in 1895, just a week after the first “Uncle Potter” item appeared. Everybody in this small town would have known the whitewash man by sight, and it seems likely the clever sayings attributed to him would have made him target for cruel boys and mean drunks seeking to bully someone for sadistic kicks. Any torment could only have gotten worse after the Democrat printed a drawing of him the following year along with a description that “…He has a keen wit which he punctuates with the apt originality pertaining to his race… He is quite a character and an entertaining talker. Like all his race he has a lively imagination and a highly developed emotional nature…” It was an invitation for people to expect him to perform on request.

Edmund Potter lived to be 91, dying in 1908 and continued whitewashing up to his final day. Obituaries appeared in both the Republican and Press Democrat, although neither paper could be bothered to get his first name right. He is buried in the Rural Cemetery, Main Circle 1, next to Elizabeth and his two wives, although he has no grave marker. His funeral service was conducted by Jacob Overton, the rights activist who had a recurring role in his life which was never explained.

* Robert A. Thompson, brother of Thomas L. Thompson, was County Clerk 1877-1884, then appointed U.S. Merchandise Appraiser in San Francisco 1885-1892. He ran for Secretary of State in 1898 and lost by 0.7% of the vote; he said he would call for a recount but nothing became of it, perhaps due to the expense or because Democratic party officials wanted no part in would have been the first contested office in state history. He first edited the Democrat in 1871 and apparently continued to be involved sporadically until it was sold in 1897. Robert authored two well-regarded local histories and an essay on the Bear Flag Revolt, all of which are available online. At his death he was working on a history of California. Thompson had a renowned library which supposedly contained many unique diaries and other primary sources, but what happened to it is unknown (my personal belief is the family donated it to the California Historical Society in San Francisco and it was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake). He died Aug. 3 1903 and is buried in the Rural Cemetery Main Circle 184. |

HUDSON-Near Santa Rosa, Nov. 21, 1876, Lizzie Hudson (colored), aged about 50 years. Funeral from her late residence tomorrow (Tuesday) at 2 o’clock. Friends are requested to attend.– Daily Democrat, November 20 1876

BURNED TO DEATH.—On Sunday afternoon, May 23rd, Mrs. Martha Potter, wife of Edward Potter, a colored man who lives on a ranch near the Poor Farm, fell asleep with a pipe in her mouth, from which her clothes caught fire, burning her so severely that she died from the effects on Saturday evening. Her husband, who was asleep in an adjoining room, heard her struggling with the flames and going to her assistance, tore the clothes from her person, but she was so severely burned about the abdomen that death resulted as above stated. She was sixty-nine years of age,

– Sonoma Democrat, June 5 1880

Mrs. Potter’s Birthday Party.

Mrs. E. Potter celebrated her fifty-second birthday, at her home on First street, Wednesday night. About twenty of her friends and neighbors were present and sat down to a fine supper. Mrs. Potter’s health was toasted and every one wished her many happy returns of the day. Afterwards music and songs were rendered. All those who were fortunate enough to be present at this birthday party will long remember the happy occasion.

– Sonoma Democrat, April 6 1895

The above is a picture of Edmund Potter, better known as “Uncle Potter”, a highly respected citizen of Santa Roaa, from an excellent pen sketch made by our artist. Uncle Potter is 76 years old and black as coal but his mind is bright and his heart is as kind as any white man. He has a keen wit which he punctuates with the apt originality pertaining to his race. Uncle Potter was born in Maryland and came to California soon after the war set him free. He has lived in and around Santa Rosa for a number of years. Many of his bright sayings have appeared at various times in the “Gossip” column of the Democrat. He is quite a character and an entertaining talker. Like all his race he has a lively imagination and a highly developed emotional nature, if he had his way he would colonize all the colored race in Africa where they could work out their own destiny by themselves. Uncle Potter is wonderfully well up in the Scriptures and is a strict constructionist of the word. He has built his house of faith upon the rock and not upon the shifting sands of doubt.

– Sonoma Democrat, July 25 1896

Edmund Potter, the gentleman of color, better known as Uncle Potter, wants to go to Liberia in Africa, where many men and women of his own race and color are located, who speak the English language. Potter thinks he can do them good and he is circulating a petition to raise money enough for transportation. On his arrival in the dark continent he will devote himself to missionary work.

– Sonoma Democrat, March 13 1897

UNCLE POTTER DIES SUDDENLY

Well Known Negro Lived to be 91 Years OldEdwin Pendleton Potter familiarly known about this city as “Uncle Potter,” the well known negro, passed away suddenly at his home on First street Thursday morning. He was in his usual good health early in the morning and had arisen and was about the house when he was taken with a pain in his back just over the heart. He lay down for a time and seemed to be getting better when he was taken with an attack of coughing and attempted to rise up, but sank back, and his step daughter ran to his side, but it was seen that the end was near. He died in a few minutes and before Dr. G. W. Mallory, who was hurriedly sent for, could arrive.

Deceased was born in Caroline county near Denton, Maryland, and was 91 years of age. He came to California and settled in Santa Rosa in 1872 and has resided here ever since. At the time of the war he had a sister who had been a slave in Virginia, but had run away, and after everything became righted he got into communication with her from this city and it was on her account that he was brought here. He was a slave himself and was sold some four or five times. He was twice married and both his wives were buried in the local cemetery and it was the old man’s wish that he be laid away by their side.

At one time “Uncle Potter” was one of Santa Rosa’s wealthy men and formerly owned the site where the new postoffice is soon to be built. He was also owner at one time of the ranch which is now the county farm and hospital. he was a very active man and right up to the time of his death was engaged in business. He was planning for another job of whitewashing on Wednesday and would have made some of the arrangements about his spray machine today.

“Uncle Potter” was of the Baptist faith but had joined the Holiness band here and was one of Elder Arnold’s great admirers. Hie was a great hand to attend church and took a great interest In religious affairs.

The arrangements for the funeral have not yet been made but will be announced in a day or two.

– Santa Rosa Republican, June 4, 1908

‘UNCLE’ POTTER HAS GONE TO HIS REST

Aged Colored Man Who Was for Many Years a Resident of Santa Rosa Dies Thursday Morning“Uncle” Edward Pendelton Potter will no longer be seen trundling his little cart and its whitewash outfit along the streets of Santa Rosa on week days. Neither will he be noticed, dressed in his best black suit and wearing his silk hat, tottering along towards the little Holiness Chapel on Humboldt street where for years he was one of the most regular of Pastor Arnold’s flock on Sunday.

The old colored man, for so many years a noted character about town, is dead. His life of ninety-one years ended suddenly at his humble cottage on First street Thursday morning where a step daughter has kept house for him. A sudden fit of coughing came on, Dr. Mallory was sent for, but before he could reach the house, “Uncle” Potter was no more.

The deceased had lived In Santa Rosa for almost thirty-seven years. Years ago he owned considerable property, but it all slipped through his hands. He was a good old man. and no one could be found about town on Thursday. but what spoke of him kindly, and with words of esteem. He was a Christian and in his humble way he lived his religion. He was a native of Maryland and in the days of slavery he knew what it meant to be sold as a slave four or five times. He was twice married and in the local cemetery he has a family plot where on Sunday afternoon he will he burled. The funeral will take place from Moke’s Chapel at two in the afternoon.

“Uncle” Potter was a very poor man when this world’s gifts are considered. Dr. J. J. Summerfield. as the representative of many of the old man’s friends, who are anxious that he shall be given a decent burial in his own plot, last night started out with a subscription list to collect enough money to have everything neat at the funeral. The people Dr. Summerfield approached last night were only too glad to give a donation towards the burial expenses.

– Press Democrat, June 5 1908

“UNCLE” POTTER SLEEPS IN SILENT TOMB

In the family plot in the old cemetery on Sunday afternoon they laid “Uncle” Potter to rest. Many old-time friends of the venerable and respected man gathered at the graveside to witness the last rites. The casket was covered with flowers and these in turn were laid on the newly made grave. The funeral took place from Moke’s chapel and the services were conducted by Elder J. M. Overton.

When the band accompanying the Woodmen’s parade met the funeral procession a halt was called, and while it passed by the band played “Nearer My God to Thee.” The sentiment of the hymn was particularly appropriate in view of the Christian character of the deceased and also because it was one of his favorite hymns.

– Press Democrat, June 9 1908

The colored citizens of Santa Rosa offer their heartfelt thanks to Dr. Summerfield and the friends of our departed and much respected fellowman “Uncle Potter,” who so kindly respected his memory with flowers, subscriptions and by giving him a good Christian burial.

The tribute paid by the Santa Rosa band and the W. O. W. touched our hearts. Trying to emulate the life of that grand old Christian, we are, very gratefully.

The Colored Citizens, by

Willis Claybrooks, John W. Dawler, Committee.– Press Democrat, June 9 1908

At the Holiness Chapel at 11 o’clock this morning there will be a memorial service for the late “Uncle” Potter.

– Press Democrat, June 14 1908