Brainerd Jones designed high-fashioned mansions and simple homes; he was adept with both the old styles and the avant-guarde. If there was any other architect as versatile as this, I do not know who it is.

But he had no formal training. He did not study architecture at any college, nor did he apprentice at a major architectural firm. His only credentials were having worked as a carpenter and a draftsman. Yet there he was at the turn of the century, hanging out his shingle as an architect.

This is the first part of a presentation made at the Petaluma Historical Library & Museum on October 20, 2018, and explains the developments in late 19th century architecture which had the most impact on Jones. Part two covers his background and some of his residential architecture up to 1906.

When Brainerd Jones was born in 1869, America was mainly a nation of plain Greek Revival farmhouses, federal style and assorted regional styles that didn’t travel very far from where they emerged. Builders had limited skills and worked without plans, having previously built nearly identical houses many times before. Builder’s guides and manuals often only contained directions on how to best follow classical principles and apply decorations.

|

| Modern American architecture started after the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia as a wave of nostalgia swept the country for the first time. Probably driven in part by escapism from hardships of the ongoing Long Depression, popular books and magazines glorified America’s colonial past with sentimental tales of Revolutionary days of yore, illustrated with drawings of cozy cottages and Elysian farms, where everyone supposedly lived and worked in harmony and fought the heroic cause (the bloody and divisive Civil War had also ended just a few years before, remember). All things colonial became fashionable again, particularly furniture and building styles. |

|

| Fairgoers also packed a replica New England Kitchen of 1776, where they could interact with players in colonial costumes. |

|

|

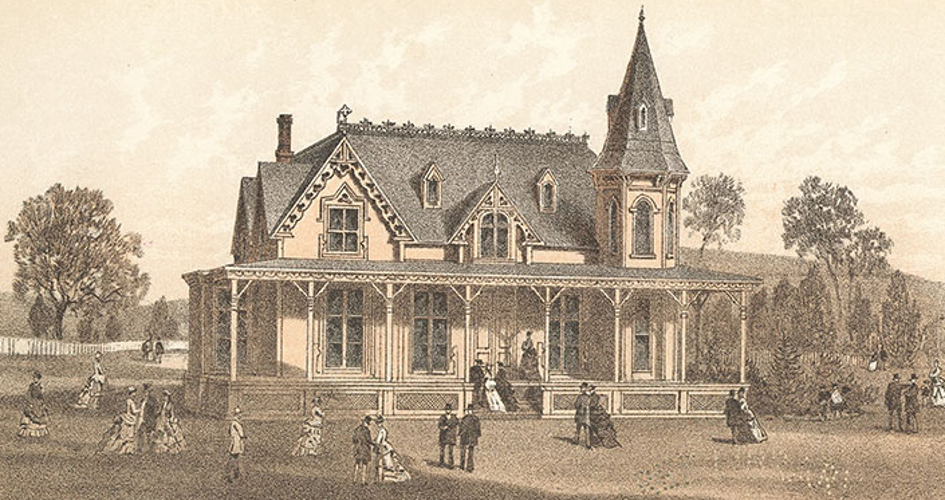

Pavilions representing the states, such as this one for Illinois, exposed the limited range of American architecture, where the Gothic style loaded with ornamentation was considered the ideal design.

|

|

|

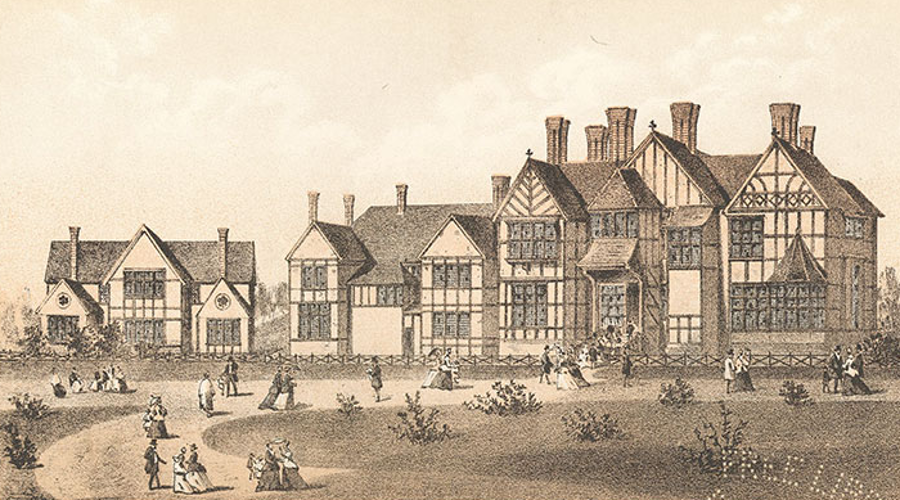

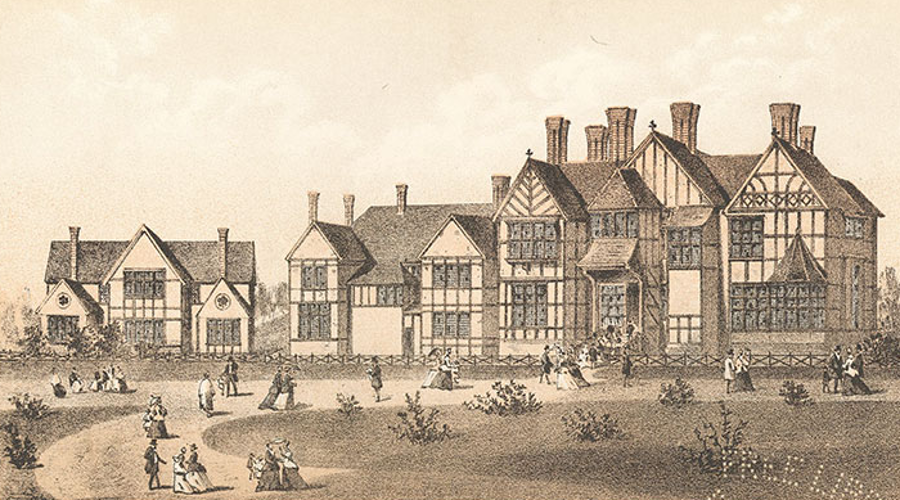

At the fair visitors encountered architecture completely unlike anything back home. Most talked about were the Queen Anne style buildings at the British compound. In England this revival style already had been popular for several years.

|

|

| The “Japanese Dwelling” presented an architectural esthetic with simple, clean lines and the highest craftsmanship; an observer said it was “as nicely put together as a piece of cabinet work.” Inside was an open floor plan without doors or even permanent interior walls. The Atlantic Monthly commented it made everything else look “commonplace and vulgar.” |

|

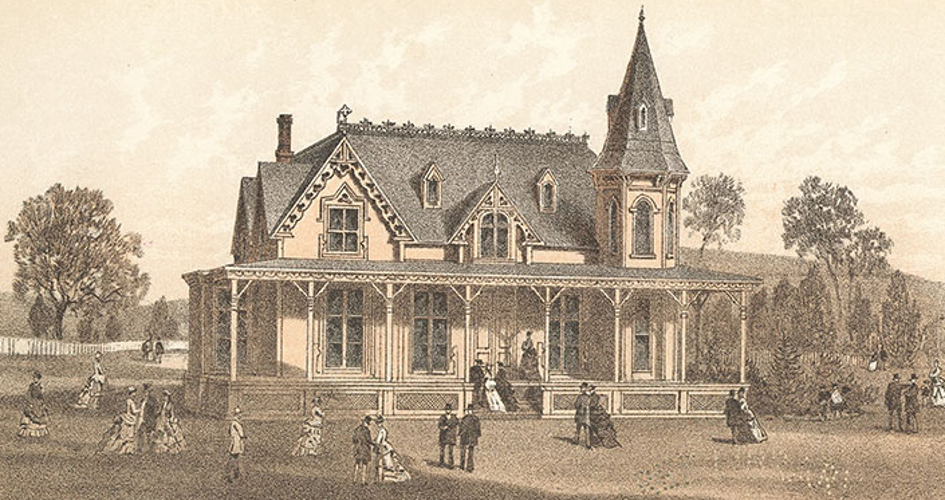

| About ten million people attended the fair, the equivalent of 1 in 5 Americans. Victorian Gothic, with its busy gingerbread ornamentation quickly lost popularity as American Queen Anne began evolving as the popular favorite nationwide. This house still has lots of scrollwork but also many of the curvy elements of Queen Anne, including a gazebo wrap. |

|

| Another transitional Queen Anne, with more curved surfaces and a prominent, irregular roof. |

|

| In a remarkably short time, Queen Anne evolved into the style we all recognize today, in all its boundless variations. But American Queen Anne lost all relationship to its historic roots; it was popular because it was a new, highly picturesque style. |

|

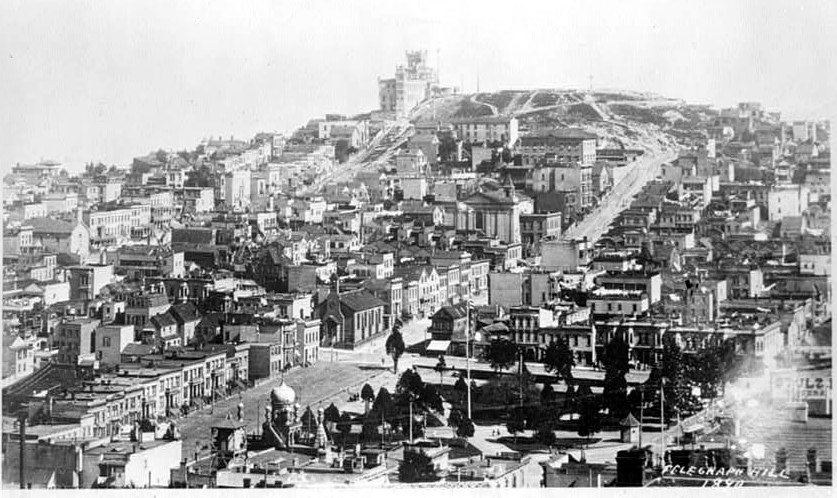

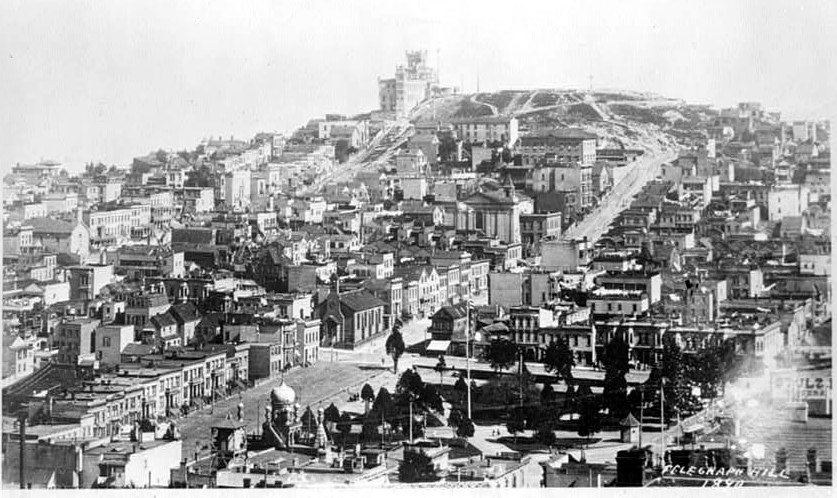

| Where the Pacific states were usually slow to adopt new trends from the East Coast, Queen Anne emerged simultaneously throughout the country; this is the 1881 Atherton House in San Francisco. |

|

| One reason Queen Annes caught on so quickly was because there was now a trade magazine that taught builders how to make those turrets and other unfamiliar elements. American Architect and Building News – which also appeared in the Centennial year of 1876 – did much to standardize construction methods nationwide. |

|

| Through the late 1880s and 1890s, Queen Annes sprouted like mushrooms all over San Francisco. |

|

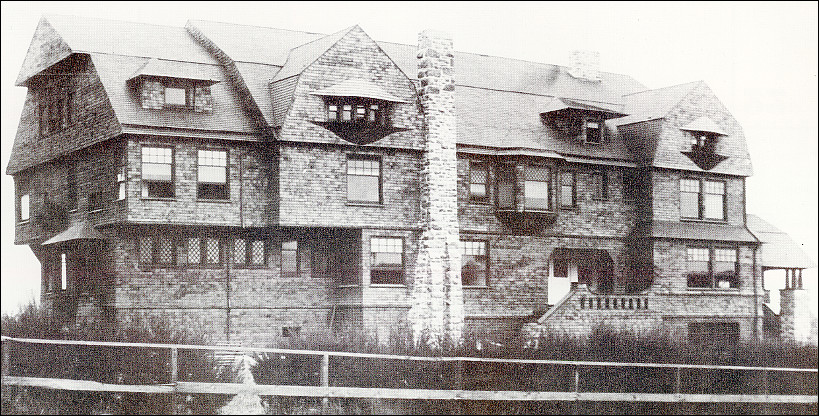

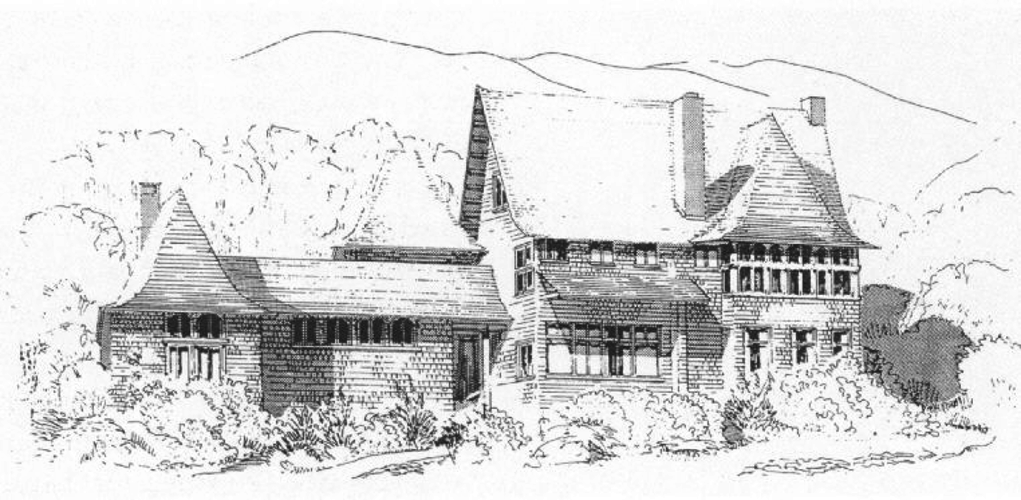

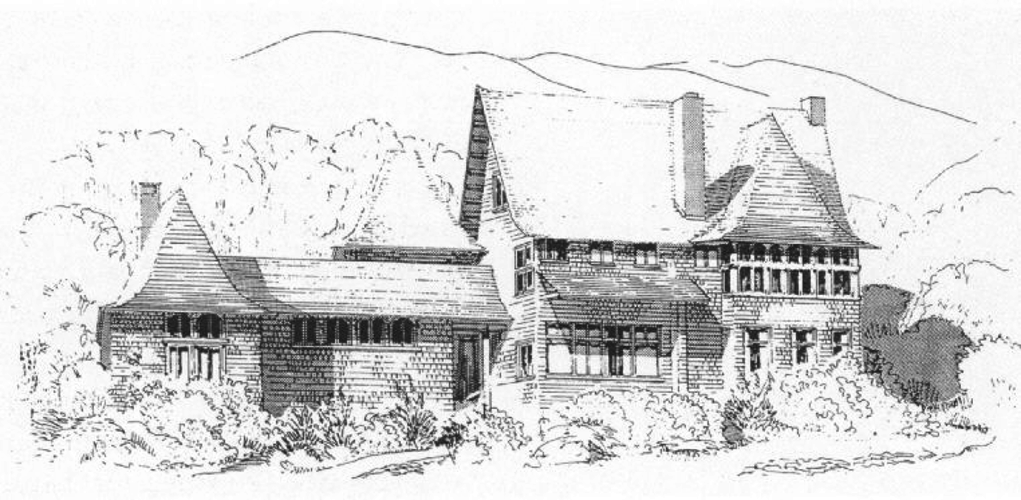

| Let’s rewind back to the Centennial Exposition to meet the birth of Queen Anne’s twin. Now called “Shingle Style,” it was really Artistic Queen Anne, created by a cadre of East Coast architects, particularly the firm of McKim, Mead and White. It mixed the Tudor elements with aspects of the Japanese building. Usually wider more than tall and with a prominent roof, the designs incorporated as many windows as possible and open interiors, which transformed hallways and vestibules from mere circulation corridors into living spaces. |

|

Unlike the popular Queen Anne style with its flashy look, these architects were consciously trying to create artistic houses that looked as if they could be centuries old. Plain shingles were sometimes aged in buttermilk or painted the color of moss. These homes had minimal ornamentation; notice here the fine latticework that suggested Asian wicker or rattan. (For more background, see my history of the East Coast Shingle Style, “ Behind the Design” with illustrations and footnotes.)

|

|

| In the letters section of magazines like American Architect and Building News and Harper’s, philosophy and aesthetics were hotly debated. For some it was a crusade to forge a unique style of American architecture, while others argued a higher objective was “unity,” which meant in part that a building must be in harmony with its setting. |

|

| And some designs look ultra-modern even today. |

|

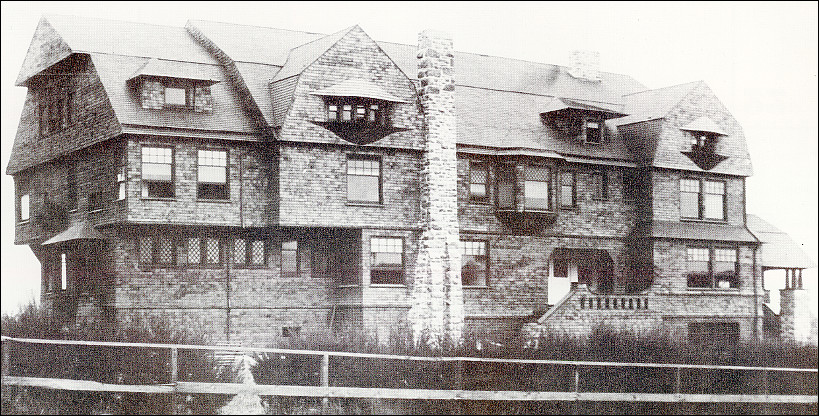

| These mammoth “cottages” were commissioned by the wealthy families of the Gilded Age living in Newport and elsewhere in New England. This is Elberon, New Jersey, which was the Newport for the nouveau riche. |

|

| While popular Queen Anne was immediately embraced by San Francisco, it took ten years for Shingle Style to arrive. The city had a reputation as a provincial backwater indifferent to the arts, including architecture. Big commissions for commercial buildings went to firms in Chicago and New York. A. Page Brown opened an office in 1889 on a trial basis and soon found himself swamped with clients. Brown hired Willis Polk, Alexander Oakey and other A-team architects from the East who had been associated with McKim, Mead and White. Bernard Maybeck worked with Brown’s firm on and off for several years. |

|

| This 1890 card party at Willis Polk’s apartment included Ernest Coxhead, whose designs straddled Shingle Style and the British Queen Anne Style. All of them were with a few years of Brainerd Jones’ age, as was Julia Morgan, who would be studying under Maybeck at UC/Berkeley in the following years. The man on the far right is Soule Edgar Fisher. (Photo: On the Edge of the World: Four Architects in San Francisco at the Turn of the Century, Richard Longstreth) |

|

| Fisher’s 1892 Anna Head school in Berkeley was firmly in the East Coast Shingle Style, avoiding any ties to popular Queen Anne. Here are some others: |

|

| A. Page Brown’s Crocker Old People’s House in San Francisco, 1889. |

|

| Coxhead’s Carrigan House, San Anselmo, c. 1895 |

|

| Coxhead’s Beta Theta Pi Chapter House in Berkeley, 1893 |

|

| Coxhead’s Churchill House 1892 Napa, now Cedar Gables Inn |

|

| Maybeck house for Charles Keeler, 1895 |

|

| Hearst’s Wyntoon, which involved Willis Polk, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan |

|

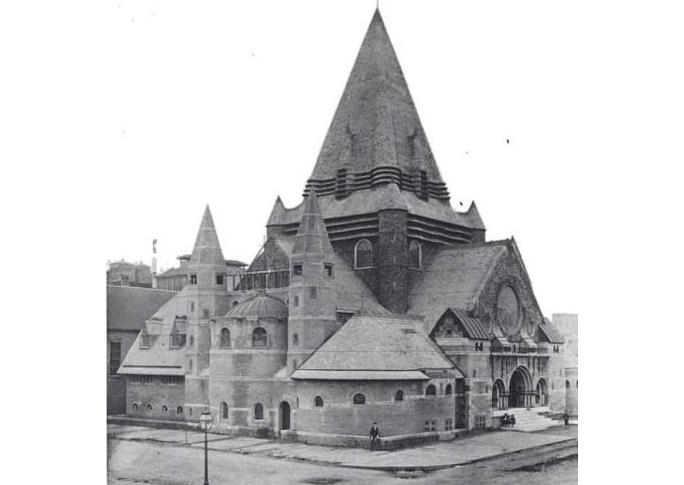

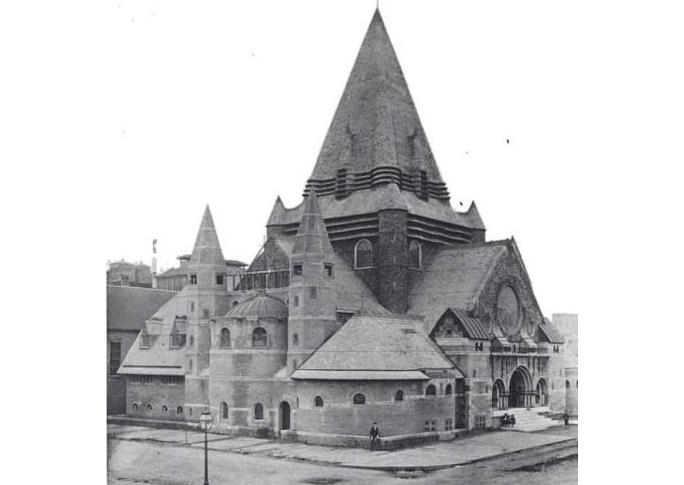

| Coxhead’s 1890 St. John’s Episcopal Church in San Francisco |

|

| American Queen Anne and Shingle style architecture are two of the three significant influences on Jones as he began his career. The last element was the news stand. Trade periodicals had taught builders how to make a Queen Anne but in the mid-1880s, general public interest in home design was strong enough to support periodicals. Shoppell’s was the most popular, selling about 10,000 copies of every issue by the turn of the century. |

|

| George Barber’s pattern books were the other main source for “mail order houses.” More than anyone else, Barber established the American Queen Anne style. His firm sold plans for over 20,000 houses, but it’s likely a far greater number of houses were built without buying blueprints, instead improvised from the floor plans and basic drawing shown in his pattern books. |

|

| Barber launched his monthly “American Homes” in 1895 to appeal to a wider audience of people who may not be building in the near future. The magazine included poetry and general interest articles with many photographic illustrations. |

|

| Keith’s Magazine was somewhat like the nerdy Popular Mechanics/Popular Electronics magazines of the mid 20th century. Plenty of DIY projects and technical articles aimed at builders and architects. When Barber’s American Homes ended publication the firm’s designs were featured here. |

|

| Magazines with enormous circulations such as House Beautiful began presenting readers with more articles about modern trends in residential design. Even Country Gentleman, the oldest magazine aimed at rural America, began running articles about modern architectural design. (This issue is from much later, but the cover is a personal favorite.) |

|

| Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman was a true general interest magazine, with short fiction, poetry, children’s stories as well as in-depth articles about all kinds of art, particularly fine furniture and home decoration. The magazine popularized the word, “bungalow” and nearly every issue included a “Modern Craftsman” house design following the clean look of the Arts & Crafts movement, free of decoration and with exposed construction elements, Stickley’s houses meshed with the philosophy of John Ruskin, who promoted skilled craftsmanship and the pleasures of a simpler way of life. |

A group of magazines such as shown above is probably what Brainerd Jones saw on the coffee table (or dining room table, more likely) when he first met with a new client. With so much exposure to modern architecture through popular media, they probably already had strong opinions about the kind of home they expected Jones to design, making it more of a collaborative effort with the architect than we have today, where a client is expected to pick a design from the contractor’s brochure. This helps explain why Jones’ work represents so many different styles.

NEXT: YOUNG BRAINERD JONES

Related

I was sorry to miss the presentation at Petaluma Historical Library and Museum Saturday afternoon and am most grateful to Katherine Rinehart for sending this link. I lead walking tours in Petaluma and enjoy learning more about Brainerd Jones’s work and it is interesting to see what influenced him.