It’s hard to imagine a worst curse: May you be remembered through the words of a lunatic who hated you.

(RIGHT: Mary Ellen Pleasant photographed by the San Francisco Chronicle, 1899)

(RIGHT: Mary Ellen Pleasant photographed by the San Francisco Chronicle, 1899)

Our story so far: Mary Ellen Pleasant – AKA “Mammy” Pleasant, although she never replied to anyone using that racist nickname – was an African-American woman of historic importance before the Civil War and during San Francisco’s Gilded Age. Almost everything we know about her is filtered through the views of Teresa Bell, who lived with her nearly every day for at least thirty years and kept a diary. In the 1950s her diary was used to write a popular fictionalized biography, “Mammy Pleasant,” and today, almost all that can be found about Mary Ellen Pleasant – both online and in print – flows from that book with its wild stories of Pleasant running a bordello, practicing witchcraft, blackmailing, murdering and doing every other kind of evil deed imaginable from her spooky “House of Mystery.”

Ignoring the novelization’s invented dialogue and tacky purple prose, the credibility of the book rests on the accuracy of the diary and its author’s truthfulness. But here are two important facts not revealed in “Mammy Pleasant:” In 1899 Teresa Bell abruptly turned against Pleasant and did everything she could to destroy her old friend’s reputation, even after Pleasant died in 1904. Also important was this: Teresa Bell was barking mad.

(By the way: If you haven’t read part one of this series, “Seeking Mammy Pleasant,” some of the rest may be hard to follow.)

Bell was the wealthy widow of one of the Comstock Lode “bonanza kings” and spent the last thirty years of her life as a semi-recluse at her Beltane Ranch, halfway between Kenwood and Glen Ellen. Her days as a San Francisco socialite were long past; when she was mentioned in the papers it was usually because she was in court either being sued by creditors of her long-dead husband or fighting her grown children who were demanding greater access to daddy’s bank accounts. After she died in 1922, however, her name was on Bay Area front pages for weeks.

With her estate worth an expected $1,000,000, she left a will dividing it between the state, San Francisco orphanages and retirement homes, with the remainder going to “cousins if any are living” – a vague bequest made further difficult because she had claimed at various times to be from different families. Predictably, many “long-lost cousins” came out of the woodwork to claim a share of the fortune.1

To her five surviving children she left five dollars each, along with the denial she was the mother of any of them. It was surprising that she disavowed the entire family, but over the years as the children took her to court over inheritance issues, her first act of defense was to claim the plaintiff was no relation whatsoever. As needed by the particular suit, she swore under oath she was the mother of five, four, two, one and none of them. She insisted oldest son Fred, the first to take her to court, was just some foundling her husband took in before her marriage – but towards the end of her life, Teresa told a visitor he was her only child by blood.2 Courts heard from elderly priests clutching baptismal records and from so many people who claimed to be present at the actual birth of a particular heir there must have been a stand of bleachers in the Bell bedroom to accomodate them all.

The children sued to have the will thrown out on basis of Teresa Bell having an unsound mind. Naturally, they insisted it wasn’t about the money at all but rather keeping the family intact.

Newspapers had a field day when the court hearings revealed Teresa was addicted to a potent cocktail of opium and alcohol and suffered wild hallucinations. She believed she could fly and had “gazed from space into the face of her murdered mother.” She could draw electricity from the earth and light candles with the tip of her finger. A neighbor told the court she enjoyed “pounding the piano and shrieking at the top of her voice in no known tune.” A ranch worker testified she could have a violent temper and best avoided when she was “drinking paregoric and carrying a nine-inch dagger whenever she went about the ranch.” Another fellow said he was hired to prospect on the ranch for platinum, gold and diamonds which she insisted were on the property.

Bigotry was another recurring theme in her madness. The Chronicle reported testimony she thought “Italians” had rustled about 10,000 cows from her ranch (which would have been so many they would have had no room to move) and “she had often floated over New York city; that she had looked down from such serial excursions and had been attracted by the gleaming white eyeballs of negroes…” Her personal racism is significant because right after Teresa split with Mary Ellen in 1899, there was a particularly vicious court speech by Bell’s attorney attacking Pleasant as a “Black Mammy of the South…robbing and plundering” her employer.

San Francisco was titillated by the revelations that came out over six weeks of testimony (or at least, it delighted newspaper headline editors, who exhausted every possible combination of words such as, “Eccentric” “Heiress” “Insane” and “Delusions”). A surprisingly large amount of press coverage was presented as illustrated features, rehashing life in San Francisco’s Gilded Age and the Bell family’s connection with the mysterious and sinister Mammy Pleasant.

But San Franciscans were unaware that ten years earlier in 1913, the Santa Rosa newspapers had reported an incident at Beltane ranch which exposed Teresa Bell’s madness. The Press Democrat reported John Ritzman, a local carpenter, said Teresa once attacked him with a club and he had been warned to take along a gun when asking for his pay, as “she carried either a revolver or a dagger.” She refused to pay him the $100 (about three months’ work at the time) and ordered him to go away, threatening to beat him again. Ritzman admitted to pulling his gun and firing before her son-in-law intervened. The tale had an unusual twist in Ritzman’s wife being a former acquaintance of Teresa’s, although she was now in a sanatarium because Teresa had gotten her hooked on drugs and liquor.

It seemed the Santa Rosa papers didn’t know quite what to make of this business. Like Rudolph Spreckels and Thomas Kearns, she was mostly unknown in Sonoma county beyond the borders of her Valley of the Moon estate, so the local papers described her only in terms of money and class – “a wealthy San Francisco woman” and “a prominent resident of the valley.” The first story in the Santa Rosa Republican presumed Ritzman (who they misnamed, “Richmond”) had to be the crazy one: “He repeats constantly, even now, that he is sorry he did not kill Mrs. Bell…it is thought that he may be mentally unbalanced.”

When the case came before the court, Ritzman received a suspended sentence and two years’ probation. “The shot, it is said, was fired after considerable provocation,” the Press Democrat commented with no further detail, again probably deferring to her status. No matter what the court heard about the exact nature of the provocation, the episode had all the hallmarks of the stories which would come out in the fight over the will.

Even though the 1923 coroner’s jury didn’t hear about that story, it didn’t take them long to decide that Teresa Bell was of unsound mind when she wrote her will back in 1910. As a result, all the money went to the children.

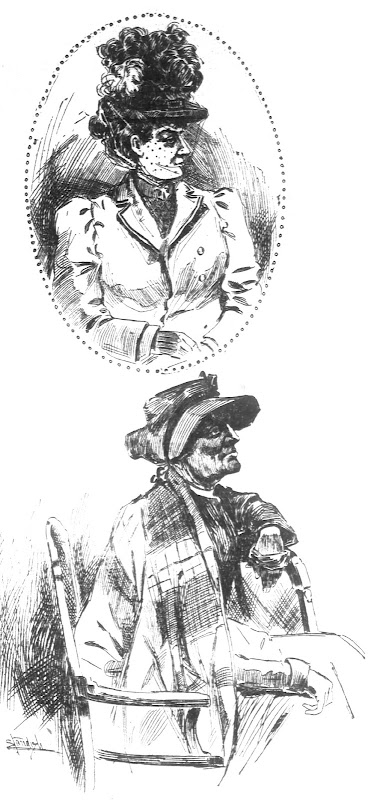

(RIGHT: Teresa Bell and Mary Ellen Pleasant as drawn by a courtroom artist for the San Francisco Chronicle, 1897)

(RIGHT: Teresa Bell and Mary Ellen Pleasant as drawn by a courtroom artist for the San Francisco Chronicle, 1897)

Normally our story would end there, with all the players dead and soon to be forgotten – but this is no ordinary tale. Just a few months after the will was settled, a new stage play began performances in San Francisco: “The Cat and the Canary” was a murder mystery set in an old dark house with a mysterious servant named Mammy Pleasant. The reviewer in the San Francisco Chronicle remarked, “Mammy Pleasant dominates the play, for one is never sure just what she may do at any moment. She seems capable of murder or witchcraft or some other horrible deed.” Now Mary Ellen’s reputation was being trashed anew for the entertainment of the bathtub gin generation. The play was made into a hit movie a few years later and several other film adaptations followed.

Those biographies written in the 1950s – which again, are the basis of almost everything repeated about Mary Ellen Pleasant today – are better viewed as novels about the backstory of the spooky Mammy Pleasant character in “The Cat and the Canary.” Which really is no surprise because they used the same primary source material: The mad, hateful ravings of Teresa Bell after she broke with Pleasant in 1899. But a playwright is not held to the same rigor as someone who claims to be a biographer such as Helen Holdredge, who had the further advantage of owning Teresa’s diaries which offered proof positive she was insane. Yet Holdredge embraced every crazy allegation in the diary as holy writ while ignoring parts which revealed she was out of her mind from drug abuse or mental illness or both. Critics of Holdredge further point out she covered up or whitewashed episodes which reflected poorly upon Teresa, including the nature of her ties to the odious James E. Brown Jr. and Bayard Saville, discussed further below.3

Ultimately every serious discussion of Mary Ellen Pleasant wanders off into a resentful rant against Helen Holdredge, and justly so. Her books were immensely popular even though she flunked as a truthful biographer, a factual historian and even as a competent writer. Want an example? Unpeel this sentence: “The rooms of the Octavia street house now contained something malevolent; the endless mirroring of the walls and the prisms hanging from the rock crystal chandeliers no longer reflected the lights and colors of the spectrum. Instead, they caught and held the dark and evil reflection of unspeakable things.” Golly.

To those literary and objective sins I’ll add another: It’s unforgivable that Holdredge also screwed up the climax of the story. Besides the death of Thomas Bell, the most significant event in the lives of Mary Ellen or Teresa since they met in the 1870s was their abrupt and emotional separation. Holdredge devotes less than four pages to the events, and much of that is made-up dialogue.

In that version, Teresa was confronted by a farmhand from the Schell ranch in the Sonoma Valley who demanded his wages, telling a surprised Teresa that Mary Ellen had always paid workers on that ranch.4 The women began to quarrel over that, followed by arguments over who owned pieces of furniture. It went on for days. Teresa ordered her evicted from Beltane ranch and the San Francisco mansion. Ironically, Mary Ellen actually owned both properties but could not admit it – she had just claimed to be insolvent in court and if she showed proof of ownership, creditors could not only seize the properties (see part one) but she could also go to jail for perjury. Mary Ellen Pleasant was in a catch-22, or, as Holdredge wrote in her perfectly awful prose, “Like the blue goose flying over the Louisiana swamplands, she had exposed herself to Teresa, crouched hidden behind a blind.”

As to what really compelled Teresa to completely break with Mary Ellen, Holdredge vaguely suggests in the months prior to the April, 1899 breakup her resentments were growing as she was feeling more self confident. Teresa wrote it was a “blessing” to learn some old business foes of her late husband had died, “a release from years of doubt and pain.” She was angered to discover Mary Ellen was allowing an impoverished widow to live on another of the Glen Ellen properties. She felt newly empowered by having done her own shopping for the first time in ten years (!) and having recently stolen from Mary Ellen some papers she felt rightfully belonged to her. Never, of course, did Holdredge mention Teresa’s insanity or drug addiction as a possible contributing factor.

Clearly something was seriously wrong with Teresa. Published excerpts of her diaries show her feelings shifted from a childlike devotion (Oct. 1898: “Outside of Mammy the world is empty to me” to blind hatred of the “she-devil” (May 1899: “Mary E. Pleasant has been my evil genius since the first day I saw her…a demon from first to last”). An armchair psychologist might diagnose this as someone with borderline personality disorder “splitting” – emotionally flipping from viewing someone as completely good to completely bad. That may be true although there was another crucial factor: Teresa’s hateful feelings were being fed by a man named Bayard Saville.

Speculate all you like about the nature of the relationships between Thomas Bell, Teresa and Mary Ellen Pleasant – and goddess knows people have been doing lots of lurid speculating for nearly 150 years – but this is a fact: Teresa thought Bayard Saville was the love of her life.

Saville appeared on the scene in 1894, less than two years after the death of Teresa’s husband. He was aristocratic (old Boston family) and charming and handsome and rich and ten years younger and looking for a wife. Of course, he was actually a con man.

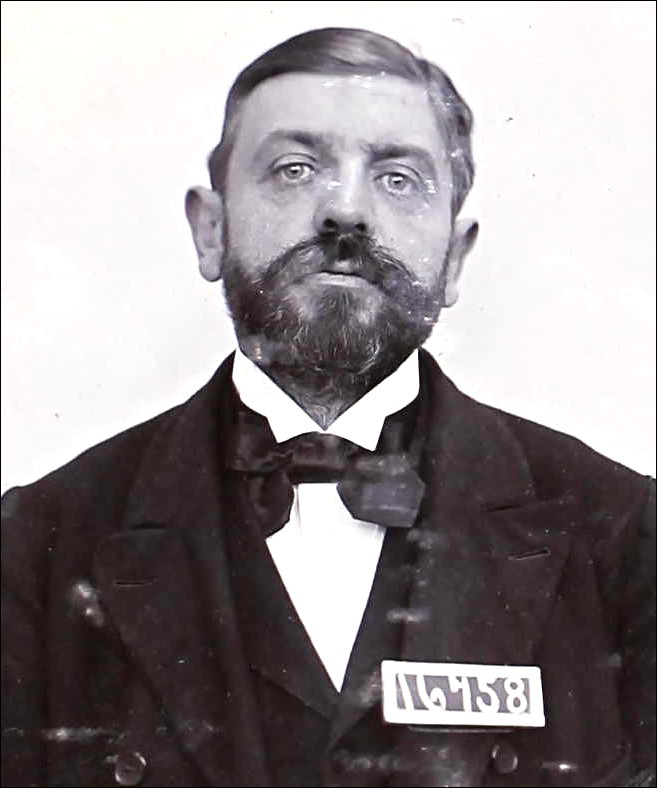

(RIGHT: Bayard Saville mug shot, 1896)

(RIGHT: Bayard Saville mug shot, 1896)

Teresa waxed poetic in her diary about his visits to Beltane ranch, where they hiked and rode horses and did whatever she recorded with an “X” in the diary. “Went riding with Saville–X X X X,” was one entry. “These X X X are to remember something I never wish to forget.” Soon she named him manager of the ranch and soon after that they told the family they were engaged.

Pleasant or her lawyers discovered he was recently released from San Quentin where he served three years for passing rubber checks and forgery. Eldest son Fred rushed to Glen Ellen and confronted Saville, threatening to shoot his mother’s lover. It was partly because of their affair that Fred later tried to have his mother declared incompetent and removed as guardian of the younger children.

True to form, before they could be married Bayard forged Teresa’s signature on two checks, for $75 and $600 (more than an average annual income) and tried to pass them at the local drugstore. When arrested, the Call newspaper reported, “Mrs. Bell would not appear against him, as she was not only in love with him, but dared not make him her enemy.” In 1896 he began serving a fourteen year sentence in San Quentin.5

The next year Saville gave the San Francisco Chronicle a jailhouse interview where he complained Mary Ellen set him up, then lied to Teresa about paying his defense lawyers. He vowed revenge: “In my safe in the deposit vaults I have over a hundred documents concerning Mammy’s manipulations with the Bell and Schell estates, and when the right moment comes I intend to have no mercy on her.”

Saville’s determination to destroy the relationship between Mary Ellen and Teresa is shown in his letters smuggled out of prison where “he told his lover she was doomed if she didn’t get rid of [Mary Ellen],” according to what historian Lerone Bennett Jr. found among the Holdredge papers at the San Francisco Library. Saville’s threat of blasting out a cache of incriminating documents is mirrored in an odd thing Teresa said in her big fight with Mary Ellen – that she had cataloged Mary Ellen’s wrongdoings and mailed the proof to the Bancroft Library at UC/Berkeley (not true).

Nor was Saville alone in poisoning Teresa’s addled mind. She was in regular contact with writer James E. Brown Jr., a yellow journalist who would later burglarize Pleasant’s home with Teresa’s approval. It was Brown who convinced her Mary Ellen had killed her husband to stop him from changing his will. (Teresa famously later wrote in her diary that Pleasant not only pushed him over the railing but “put her finger in the hole in the top of his head and pulled out the protruding brains,” which would have been quite a feat considering his skull was unbroken.)

Although there was no byline, we know from Teresa’s diaries that Brown was the author of the “Queen of the Voodoos,” a feature in the Sunday Chronicle, July 9, 1899, which was about six weeks after the big quarrel and breakup. That she was named as “Mary Ellen” once and “Mammy” 49 times is about the least offensive thing about the article, which casts her as a sorceress, master manipulator and probably the least likable character since Simon Legree. No good deed is mentioned, even the smallest act of charity; the article is a matter-of-fact rehash of old gossip and awful rumors about her consumate evilness, including her “trapping” poor Saville. It probably goes without saying that many of the lies made their way into the Holdredge novelization.

“Queen of the Voodoos” was naked libel, but Mary Ellen was in no position to sue the Chronicle – she was claiming to be insolvent at the time, remember – so the article was left unchallenged. The bemused reader likely thought it to be an objective profile; after all, it carried the misleading subhed, “Remarkable Career of Mammy Pleasant and Her Wonderful Influence Over Men and Women.” Few were still around who remembered most of the events described in the article.

And that’s how Mary Ellen’s actual history came to be erased. While there had been ongoing newspaper items over the years concerning the creditor lawsuits and the earlier Sharon-Hill court fight, by 1899 she was half forgotten. An entire generation and more had passed since her glory days in the Gilded Age, when her team of horses famously raced through San Francisco streets carrying the proud black woman. All her enemies had to do was NOT remind people how she had utterly demolished race and gender stereotypes, building a fortune in the process. Without that, her narrative invited suspicion: How could a woman of her era – particularly an African-American woman – become so wealthy by legitimate means? Brown, Teresa and others were ready with stories to tell you.

Mary Ellen Pleasant died January 11, 1904 at the home of a married couple. The obituaries were mostly kind, insomuch as they often mentioned her association with abolitionist John Brown as well as supposed voodoo rites. Popular descriptors were “weird,” “mysterious” and “strange.” She left several wills, including one which named only the Bell children. Six years later it was decided everything went to the couple who nursed her, including Beltane ranch, now reduced to just 114 acres. That didn’t sit well with Teresa, who kept Mary Ellen’s estate in court until her own death in 1922.

When she wasn’t appearing in a courtroom, Teresa Bell spent most of her last thirty years at the ranch outside of Glen Ellen. After being dependent upon Mary Ellen for most of her life, forcing away her old friend and mother-figure was the most Pyrrhic of victories; as she was usually estranged from all of her children she was left with only a blind servant for companionship. Despite her foolishness and the troubles she caused so many, it’s hard not to feel sorry for Teresa when you imagine her there in the Valley of the Moon as decades crept by, always alone except for the voices she heard on the winds and the mad visions she saw as she flew.

1 Teresa Bell was born in 1846 or 1847 near Auburn, New York. Two women who said they were her birth sisters told the probate jury she was born Marie Clingan and taken in by a family named Harris when she was about four, following the Clingans being sent to the poor farm. Supporting this interpretation is the 1855 New York state census which shows 9 year-old Teresa Harris in the Harris household, but not there in the 1850 federal census. But the coroner’s grand jury also heard testimony she sometimes flipped the story, claiming she was born a Harris and adopted by the Clingans. “Whether she really believed herself a Harris or tried to make the world believe it, no one knows,” the Chronicle reported. An article in an Auburn newspaper (reprinted in the Oakland Tribune, Jan. 20 1881) confirms she was born a Clingan but also lived at two other homes besides the Harris family. She returned to visit Auburn at least twice, in 1872 with her first husband John Percy and in 1881 with her five year-old son.

2 A profile from an Auburn, NY newspaper (reprinted in the Oakland Tribune, Jan. 20 1881) stated she had “two children, and one more by adoption” with the adopted child being Fred, the eldest.

3 “The Mystery of Mary Ellen Pleasant,” Lerone Bennett Jr., published as a two-part article in Ebony magazine in 1979 and reprinted in 1993. A noted scholar and author of several books on African-American history, Bennett did original research in the Mary Ellen Pleasant document collection donated to the San Francisco Public Library by Helen Holdredge. His articles contain many details not mentioned in other research on Pleasant such as the condition of the Teresa Bell diaries, where “several pages and parts of pages have been cut out with a razor blade or some other sharp instrument.”

4 As per usual, it is difficult to determine if there was any truth to what Helen Holdredge wrote about this episode. According to her book (“Mammy Pleasant”, pp. 224-227) Lucy Beebee was Mary Ellen Pleasant’s last protégée and among the Sonoma Valley properties purchased by Mary Ellen in 1891 was a ranch given to Fred Schell, Lucy’s brother-in-law. As a farmer Schell was such an abject failure, Holdredge continued, his wife “did not know whether she would have a pot of beans from one day to the next” and Pleasant was secretly paying his farmworkers. In truth, Lucy appears to be Fred’s cousin, as his mother’s maiden name was Beebee. The Schell family was well-established in the area by Fred’s father since before the Civil War with the Schellville railway station and crossroads village named after them. After several years of office work, Fred returned to farm on “the old homstead” in 1896, according to the Honoria Tuomey county history. In 1899 – the same year that Schell farmworker supposedly demanded his wages from Teresa – Fred established the successful Schellville Hatchery which shipped eggs and chicks all over the west.

5 Saville was released from prison in 1911. It is unknown if he again contacted Teresa in person. He lived in Santa Cruz and died in Venice, California in 1914.

Oil was found on Southern California property Teresa Bell inherited from her husband, and in 1905 she became a millionaire in her own right

John Ritzman, who has been employed on the old Mammy Pleasant ranch, near Glen Ellen, by Mrs. Teresa Bell, relative of Mammy’s, and a wealthy San Francisco woman, told District Attorney Clarence F. Lea yesterday afternoon that when he fired twice upon Mrs. Bell with a revolver on the ranch on Monday afternoon he did so because she had attacked him with a club and because prior to the near tragedy he had been warned to take a revolver with him when he went to demand of the woman a payment of his wages, as “she carried either a revolver or a dagger.” She refused to pay him the $100 she owed him in wages, he said, and when he asked her for it, he said, she called him bad names and demanded that he leave the ranch forthwith, threatened him with a club, he admitted that he fired twice at her but did not hit her. He might have fired again but his desire was cut short when John Lavere, another employee of the face hit him over the head with a water pitcher and floored him. Then the desire left him and the next thing he knew Deputy Sheriff Joe Ryan had him in custody. Deputy Ryan brought Ritzman to the county jail yesterday morning and he will be charged with assault with a deadly weapon. Ritzman’s wife is mentally unbalanced and in his interview with the District Attorney, Ritzman claimed yesterday that Mrs. Bell was responsible for his wife’s condition, as she had furnished her with liquor and drugs.

Mrs. Bell will tell her version of the attack upon her by Ritzman when the case is heard in court. Ritzman has five children.

John Richmond, a resident of Sonoma valley, was arrested Monday afternoon by Deputy Sheriff Joe Ryan and brought to this city Tuesday, where he was lodged in the county jail on a charge of assault with a deadly weapon.

Ryan states that Richmond fired twice at Mrs. Fred Bell, a prominent resident of the valley for whom he was working. Richmond was standing within a few feet of Mrs. Bell when he shot and her escape is considered miraculous. Richmond was about to fire again when another man rushed up from behind him and hit him over the head with a crockery water pitcher, knocking him unconscious.

Richmond admits the shooting and states that Mrs. Bell had been quarreling with him for several days. He is a carpenter and Mrs. Bell charged him with slighting his work and loafing on the job. He says that he lost his temper and determined to get even. He repeats constantly, even now, that he is sorry he did not kill Mrs. Bell. Richmond is a property owner in the Valley and has a wife and five children. He will be given a thorough examination, as it is thought that he may be mentally unbalanced.

Mrs. Teresa Bell, a wealthy San Francisco woman who owns a ranch near Glen Ellen, took the stand in Justice Latimer’s court here yesterday and told of the narrow escape she had when John Ritzman took two shots at her with a revolver on her ranch one day last week. Ritzman’s preliminary examination on a charge of assault with a deadly weapon with intent to murder Mrs. Bell was held yesterday and Ritzman was bound over i n a bond of $3,000 for trial in the Superior court. District Attorney Clarence F. Lea prosecuted.

Mrs. Bell testified that Ritzman became very angry when she criticized the work he was doing in the erection of a building for her. He used strong language tolde her, she said, and when she walked away he followed her. Once she picked up a stick to protect herself. Ritzman continued his abuse and ran to his carpenter’s apron and pulled out a revolver and shot at her. But for the fact that the revolver caught in the apron, Mrs. Bell, testified, the bullet might have found a mark in her anatomy. Ritzman raised the weapon to fire again, but her son-in-law. J. Rullmith, struck Ritzman over the head with a water pitcher and the shot went wild. The son-in-law of Mrs. Bell was called as a witness.

Ritzman had very little to say. Of course he could not give the bail bond and had to return to jail. He claims that he acted in Self-defense and that he had been warned by another man to look out for Mrs. Bell. He claims his words with Mrs. Bell started when he asked her for wages. The question of wages was not brought out at the examination yesterday.

John Reitzman, the aged carpenter, who took a shot at Mrs. Teresa Bell, a well known San Francisco and Sonoma Valley woman, on her ranch near Glen Ellen some time since, was allowed to go on probation after he had pleaded guilty in Judge Seawell’s department of the Superior court on Saturday. Sentence was suspended for two years and in the meantime Reitzman will report to Probation Officer John P. Plover.

The case was deemed one in which clemency could be extended. The shot, it is said, was fired after considerable provocation. Reitzman has had a great deal of trouble, his wife is in a sanitarium and he had a number of children who are dependent upon him. Ritzman was represented by Attorney Roy Vitousek. It is not likely that he will get into trouble again. Mr. Plover will assist him in straightening out his difficulties.

By all accounts Tom Bell was originally just a bank teller in the bank that Mary Ellen used and helped her with all her transactions and he put his name on her account and after his death, his wife Teresa stole Mary Ellen’s money. Otherwise, how did he amass such a fortune to make him the “millionaire”? As noted, most of the property claimed by Teresa as being owned by her deceased husband, Tom Bell, was actually owned by Mary Ellen and the courts never affirmed her claim. Thus, Mary Ellen was swindled out of her fortune by Teresa and by the courts.

As for your forewords: It’s hard to imagine a worst curse: May you be remembered through the words of a lunatic who hated you.

The real curse: Was the one Mary Ellen put on Teresa that turned her into a raving lunatic for the rest of her life, hated by her own children. If they were hers?? Even her son Fred ended up a pauper.