Dear Folks, France is just like in the movies and the French people very hospitable but their customs are strange. I am well and enjoying it over here. “Beaucoup” love, your son.

Those are the basic bones of most letters WWI soldiers sent to their Sonoma county loved ones and friends – and we know that because the Press Democrat printed hundreds of them during the war. Sometimes they were condensed down or summarized, but others were allowed to flood an entire page with small print. That was very unusual; even in rural towns, newspapers at the time provided only sketchy details of news from locals serving in the war. (Jack Cline has received a letter from Jack True in which he states that he lost his left leg in the battle at the front – Petaluma Courier, Sept. 26 1918.)

The PD printed enough letters to fill a book (which wouldn’t be a bad idea) and a sample of the ones written from France can be found transcribed below, following the roster of those who died. The paper also ran letters from England and stateside training camps.

Rarely did they write about their combat experiences in much detail (“I am now busy and happy doing my bit at the battle front”) which is understandable, as they didn’t want to worry friends and loved ones. But sometimes there are hints of the harrowing war: “We have lots of cannonading and shelling, both from our front and from the Germans, and we have gas attacks quite often. I had to wear my gas mask for four hours one day, and I have to carry it with me all the time, and also the helmet.”

As they were billeted in French villages near the front lines, their interactions with the villagers were frequent topics. “…It’s surprising how we can get along with these people and make them understand us. Not a one that speaks a word of English, but we talk by using a mixture of English. French, Spanish, German, hands, feet, ears and eyebrows.” They were gobsmacked by the amount of wine being consumed (“the equivalent of 26 cents American money would purchase the finest bottle of Port Wine or Claret ever made”) and that their pastoral country life seemed untouched by modern times (“a person here never needs an alarm clock to wake him up. There is always someone going down the street with wooden shoes and you can hear them for four blocks”).

There are many other anecdotes about village life I could excerpt here, but I’d rather you scroll down and read the actual letters which are genuine and heartfelt, revealing how the old world culture and the Americans were mutually astonished that the other existed. Okay, one more – don’t miss the story about the Frenchman who learned how to blow Taps on a bugle to impress his girlfriend, causing a wild scramble as the soldiers rushed back to camp.

But don’t presume the PD was just offering up lightweight fare about locals having a good time behind the lines. The paper also printed letters from two correspondents which contained details so raw that editors might hesitate publishing them today.

One of the letter writers was Major Hilliard Comstock, an unabashed hero of this journal. He last appeared here in 1916 as Captain of Santa Rosa’s National Guard Company E when they were sent to the Mexican border to protect the United States from Pancho Villa. Company E and other units of California’s National Guard were ordered into service in 1917 and became part of the regular U. S. Army.

Comstock caught the Spanish flu once he was overseas and spent the war behind the lines in France training machine gunners, but he kept in touch with his National Guard comrades and others from the North Bay; most of his letters are composed of their war stories.

He wrote a lengthy account of a hospital visit to a soldier who narrowly escaped dying because the bullet was slowed by squarely hitting a button of his uniform; it passed through a lung and exited his side, missing all bones and arteries. Comstock (or perhaps a PD editor) only identifies the man as “Bill H.” but from the details of his injury we can positively ID him as William Herbert. If that name’s familiar, it may be because he was recently mentioned here as a well-known Santa Rosa architect and early partner of Cal Caulkins. The amazing story below does not appear in any biographical material on him (at least, that I can find). Comstock wrote:

Comstock wraps up the story by writing that the Army would recognize Herbert’s valor and give him a promotion (he was made a lieutenant) but the British commanding officer of his battalion would not recommend him for the Distinguished Service Order because “bravery is only an officer’s duty.”

(Although Comstock was never in combat or wounded, a rumor spread in France that he had been killed. He learned of the gossip and on November 14 wrote to his wife, Helen, to disregard anything she might hear about it: “By the way, if any one has written home that story of my death, I want to say, like Mark Twain, that ‘the report of my death was grossly exaggerated.'” Unfortunately, Helen didn’t receive his letter until December 16. By then two other soldiers had written home and mentioned Hilliard’s supposed death, causing his family anguish and Santa Rosa to lower flags to half staff. Another tragic mail delay involved sisters Ruth and Viola Lundholm, Red Cross nurses from Petaluma, who died of the Spanish flu a few weeks after reaching England. A cheery letter from them about their ocean crossing arrived shortly before a cable informing the family of their deaths.)

The other correspondent whose frank descriptions of the war appeared in the Press Democrat was Constance Cooke, a Red Cross nurse from Healdsburg. From her there were no coy descriptions of the war.

After a few days in Paris she was dispatched to a large military hospital in Beauvais, on the Somme front. Her first letter described the grim scene as she drew nearer the battle zone: “As we passed through the various villages I got my first real glimpse of the meaning of the war. Saw many trainloads of soldiers, French, English, American and Algerian, many wounded returning from the front, and many fresh companies going towards the scene of action. We hear the booming of the distant cannons daily…”

Connie became inured to the sights and sounds of the nearby war, and would go outside when she heard German reconnaissance airplanes, which were sometimes involved in dogfights with French aviators. “These day air battles are exciting to watch. As a rule the machines are too high to see but we can hear their guns plainly and see the smoke from them – like small, fluffy white clouds.”

A crisis came on the night of May 29-30, as a heavy German air raid dropped bombs which landed close to the hospital and shattered windows. A French nurse and her family were killed in their home a short distance away. Cooke was among the five American nurses who moved patients to the basement and lower floors, with some patients apparently sedated by ether. For this she and the others were awarded France’s highest medal for courage, the Croix de Guerre.

Press dispatches about the hospital bombing and later the Croix de Guerre made Constance Cooke a household name in the Bay Area, claimed both by San Francisco and Sonoma county. (Nor did it hurt that she was pretty; there were three wire service photos of her in circulation.) Julius Myron Alexander wrote a really awful poem about her which appeared in the Healdsburg Tribune June 6 and was reprinted in the PD the next day: “She came from the land where poppies blow/ From the land of Western sunset glow/ Where murmuring brook and song of bird/ So soft o’er the land all day were heard/ ’Twas there the maiden grew from her youth/ Nourished in love and God’s own truth…”

When she returned home in early 1919 the Oakland Tribune interviewed her about the bombing. Although the newspaper’s article seems to have some heavy-handed editorial additions, it’s still interesting to read:

Asked if she fell in love with anyone over there, she replied, “yes, I fell in love, but with the whole Yankee army.” I know that sounds cheesey, but I believe she actually said that; read her letters below and you’ll find her tenderly describing patients as “my children.” In truth, she married San Francisco attorney Robert Wisecarver in 1920. During the 1960s she was state chairman for the USO and died at age 101 in 1989. She’s buried in the Oak Mound Cemetery, Healdsburg; stop by next November 11 and say thanks.

LIEUTENANT DUHRING NOW ON DUTY ON FRENCH FRONT

Writes Parents of Experiences and Duties Under Shell Fire of Germans—-Dal Peggetto Tells of Delay in Getting Away From Camp.

The many friends of First Lieutenant Frederick S. Duhring of Sonoma, son of Mr. and Mrs. F. T. Duhring of that city, will be interested in a letter dated in France December 6 to his parents, in which he says:

“Today I received two letters from you and a Christmas card from Mr. and Mrs. C. E. Johnson. Was sure glad to get them – the first news from home for six weeks. They were postmarked December 15th, so you can see my mail travels far before it reaches me. I am anxious to know how you spent Christmas.

“I received a letter from Don Campbell today. He was quite sick for awhile in Nice, but from his letter I judge he found that city a wonderful place in which to convalesce, and he stayed there until he was about O. K. He is now back with the old Section, now 586.

“I am about 60 kilometers down the line with my new Section, again listening to the melodious Boche shells (most odious I assure you) and superintending the work of 33 young speed maniacs hauling sick and wounded Frenchmen under shell fire. I am responsible for about ten kilometers of the front and must see that all sick and wounded are transported from the trenches to the hospitals and evacuation posts farther back from the lines. It is quite a job and when there is much activity I am kept busy. There is a fine, eager spirit amongst the crowd, the majority being old hands at this business and well understand what is expected. They were among the very first Americans who came to the aid of France three years ago.

– Press Democrat, March 8 1918

MISS CONSTANCE COOKE WRITES HOME FROM FRANCE

The following letter from the war zone was received Wednesday from Miss Constance Cooke, daughter of Editor Frank W. Cooke, of Healdsburg, who was recently reported by the press dispatcher as one of the nurses in a large hospital that was bombarded by the Huns:

At the Front, May 8th, 1918 — Please forgive me for waiting so long. It is because I’ve been “going it” as hard as ever I could for the past three weeks. All I’ve done since coming to is work, sleep and eat. I make it a point to go to bed early (10 p. m. until 6:45), so you see I have a lot of rest. Our food is served in plenty, but is not such well-balanced diet as we are accustomed to i. e., meat, is served In abundance, also cheese, jam, wine, lentils and “war bread” without butter. We’ve scarcely seen butter. green vegetables, milk or desserts since leaving New York, except for the four days at the hotel in Paris where we had butter once a day and also a green vegetable, and occasionally lettuce.

We were quite busy for a few days after arriving in Paris, getting our papers filed and accredited, and securing certain other necessary papers. One evening five of us ventured out to a moving picture show. After sundown there isn’t much light on the streets to guide one. Very few of the street lamps are lighted and those few are made dim by means of being painted with dark paint. We paid the extravagant price of 3 francs 80 centimes (72 cents) apiece for our seats. Were surprised to see a picture produced in Los Angeles – quite American. During the evening a picture of President Wilson was flashed on the screen. We clapped loudly, and as a result became the center of attraction for a few minutes. When the main picture was about finished the curtain descended and the ushers quietly informed the people that an air raid was “on.” Everyone calmly left the theater. When we got outside we heard the awful whirring of aeroplanes and the bang! bang! bang! of the bombs, and looking down the wide drive of the German Elysees we could see the glare of an immense fire caused by the bombing. At first we thought we could walk home in time but as the bombing was continued we fled with others into a nearby “abri” (shelter in a deep basement). We were too interested to stay long so [we] stood in the doorway of the building watching the flames of the bombs.

When an alien plane gets into French territory, wireless messages are signaled and a siren (“alert”) warns the people of the danger, whereupon they seek shelter in the “abris.” When the enemy has been driven away another siren sounds and bells are rung to give the signal for safety.

We have as headquarters when in Paris a splendid hotel with all accommodations and excellent food.

After four days I was sent by Miss Ashe to the Grenelle Dispensary, Paris, to do the same type of work for about a week as that in which I was once engaged at the Petrero in San Francisco. Then came an emergency call for a relief nurse to replace one who was ill, so I was hurried off on the evening train, April 20th, to ———, two hours north of Paris, and 30 miles from the front. I was accompanied by Dr. Pearson of Massachusetts, a brother-in-law of Dr. Harry B. Sherman’s wife, (whose little girl I nursed when she had measles). When we were nearing this historic town the Doctor informed me that we might be bombarded, so not to be afraid. I told him I would be quite frank to admit I that I would be afraid, but that I would endeavor to conduct myself in a quiet and orderly manner, nevertheless.

As we passed through the various villages I got my first real glimpse of the meaning of the war. Saw many trainloads of soldiers, French, English, American and Algerian, many wounded returning from the front, and many fresh companies going towards the scene of action. We hear the booming of the distant cannons daily, and the streets of the town are almost a constant stream of huge camions [sic] going in either direction.

Have had charge of a small hospital for the sickest of the refugees who pass through, on their way south. Two English girls, one a nurse and the other an aide, and an M. D., have completed the staff of the hospital. We have had lots of work organizing things, but have grown to love the little place. Sometime will send you pictures of the building and also of the town.

Expect to be transferred to a military hospital for the care of French and American soldiers tomorrow, as the refugee question in this particular district is about settled. I am glad to go, however, as now that we are “over here” we feel the American boys should be our first consideration.

Received my first letter from America. from Grace, dated April 6th. My, I was glad to get it, I assure you.

Please let all of the family read this, as I don’t know when I’ll have another chance to write. Lots and lots of love, Connie. Do write soon.

– Press Democrat, June 13 1918

MISS COOKE TELLS OF THE BOMBING OF HOSPITALS

Daughter of Healdsburg Editor Sends Another Fine Letter From “Over There” in Which She Describes Many Interesting Happenings—Red Cross Nurse Has to Be Most Versatile in Her Accomplishments for the Entertaining and the Nursing of the Sick and Wounded Soldiers.

MISS CONSTANCE COOKE has written her father. Editor Frank W. Cooke, of the Healdsburg “Tribune,” another very interesting letter from France, which will read with much interest by her many friends. Among other things Miss Cooke says:

My undertaking, as you call it, is only a drop in the ocean compared with this ghastly war. You know our ideas have changed by degrees since leaving the United States, and have come to the wonder why we did not start for France long ago. Everyone over here feels as one that no sacrifice can be too great in assisting to win the war for humanity and a higher type of “Kultur.”

My undertaking, as you call it, is only a drop in the ocean compared with this ghastly war. You know our ideas have changed by degrees since leaving the United States, and have come to the wonder why we did not start for France long ago. Everyone over here feels as one that no sacrifice can be too great in assisting to win the war for humanity and a higher type of “Kultur.”

I’ve come to believe a lot in “fellowship” since leaving the United States. My! how I crave companions all of the time. Of course, under so many precautions and in the war zone wo have almost no social life, and it is a mighty nice thing to have a few other nurses, Red Cross official and soldiers to chat with during the day’s work.

Have received two lovely letters from Florence Keene; also Grace, Edna H. and Lily have written, and then I hear often from several of the girls who came over in the unit, and from a very dear sailor aviator, whom I met on the Rochambeau.

I think I have written you since coming to Beauvais. I had the novel experience of organizing a hospital for refugees, with the very able assistance of an English nurse and an aide. After three weeks was transferred to the French Military Service, as the need is great for military nurses. You know I found, after arriving in France, that pediatrics should come second to serving our American boys, and I felt very happy to enter into the greater service. Am in a hospital where “gassed” cases are cared for, both French and American. Have been in duty for several weeks, and just love to care for the boys. Most of them havn’t seen American girls from two to ten months, and they appreciate just looking at one of their own kind again.

Mr. Censor probably wouldn’t like me to go into much detail. I wish I could tell you many things of interest. For the past few nights I have been on night duty. I just try to do everything under the sun to “coddle” the men, because It means so much to them after their experiences at the front.

We are near enough to the front to hear the cannons roar daily and nightly, and are always reminded of the proximity of the aeroplanes by their whirr overhead. The other night Mr. Fritz dropped a dozen bombs in our vicinity. As I had experienced the same thing in Paris I was not so frightened this time. Was surprised to find the patients very nervous as a result of the affair, but realized they have shattered nerves after a few weeks’ relaxation, away from the front and flat on their backs in a hospital. Six bombs dropped in the courtyard of the refugee hospital I was in formerly, crashing windows, etc. No one was killed in that particular place, but elsewhere in town. We picked up a few pieces of the shrapnel to stow away in our trunks.

The Red Cross and the Smith College Relief Unit give much comfort to the soldiers in a thousand ways, and give the nurses many things to distribute. In fact, we get just about all we ask for, i. e., cigarettes, chocolate, cocoa, canned milk, jam, tooth brushes ond powder, soap, washclothes, shaving sets, toilet paper, towels, extra pillows (you know a small pillow tucked here and there makes a world of difference. sometimes), writing material, dally papers, matches, lemons, and oranges, and even money for boys who haven’t received pay for several months. Well, all of these things gladden the hearts of our “blessees,” and all of our efforts are used to do just that, aside from nursing.

You know what a clown I can be without trying very hard. Well, I even perform at times. (Wish I had Lily here to sing). Since I have been on night duty I do all sorts of things to keep our patients comfortable and cheerful, and we have just real nice times, even when some are in throes over their various pains. Some of the men have trouble from sleeplessness, and at such limes I make chocolate or orangeade (material given by the Red Cross of Smith College unit) for them.

The other night, after distributing chocolate, various pills, rubbing the aching members of a number of patients in one ward, stuffing in a pillow here, tightening one there, etc., I found dressings over, loosening a bandage here tightening one there, etc., I found a sleepless family on my hands. So I played poker (horror of horrors!) with one of them by the light of the smoky lantern until 1:30 a. m. with the others vastly interested in the outcome of the game. We used cough lozenges for chips. Then I informed them that they just had to go to sleep, but if there was anything else they wanted before I left to say so. One sang out, “Well, if you’ll just stay here and let us look at you, that’s all we ask.” You see it’s just the idea of someone of their own kind fussing around which “hits the spot” as it were, after trench life.

So I left my children and made rounds in the three other wards. In one of them is a dear boy named Blossom — Karl Blossom — who seems to have fallen back on his nerves. I find him wide-awake at any hour I make rounds, so have taken to sitting beside his bed for an hour or two at a time in the wee small hours. Of course, I enjoy every bit of the work and am glad I finally got “onto” myself to do my bit.

We have a comfortable room at the hotel and good food. So you see I’m really quite well looked after. Our unit has been scattered all over France. I never saw Dr. Lucas to speak to, as he left France for America right after our arrival.

“Beaucoup” love, Connie.

– Press Democrat, June 27 1918

OLD FRENCH WINE CELLAR IS HAVEN FROM BOMBS

Letter From Healdsburg Man Tells of Exciting Experiences “Over There,” as Well as the More Pleasant Forms of Life.

Ancil Walker, son of Mr. and Mrs. D. B. Walker of Dry Creek Valley, near Healdsburg, has sent his folks a nice greeting from France, where he has been with the American army for over three months now. “I am safe and happy,” is his message.

These brief words were contained in a letter sent by a friend of Ole Johnson of Healdsburg. The latter happened to be writing to Johnson from France when Ancil Walker came along and wrote the note to his parents. The letter from the other writer had this to say among other things:

“I am now busy and happy doing my bit at the battle front. I am down in an old French wine cellar, since our hut was bombarded on the 20th of Aprll. I have been walking and standing around in my rubber boots most of the time, as it is muddy here. I serve the boys as they go and come from the trenches. I make coffee and cocoa, and they claim it is the best they have tasted since they came to France. We give it to them free. We sell at cost candy, nuts, figs and such things and have tables for reading and writing. We have services and entertainments for them and they sure appreciate it.

“We have lots of cannonading and shelling, both from our front and from the Germans, and we have gas attacks quite often. I had to wear my gas mask for four hours one day, and I have to carry it with me all the time, and also the helmet. We have a great opportunity here to do good.”

– Press Democrat, July 12 1918

SERGT. WILLIAMS IN FRANCE WRITES JNO. T. CÄMPBELL

Interesting Letter Sent Santa Rosa’s Well Known Citizen by Brave Soldier Fighting the Battle of Freedom ‘Over There.”

A letter from Harvey G. Williams, sergeant in the 66th Aero Squadron of the army in France, to the Honorable John Tyler Campbell is of much interest. Among other things he says:

I received your letter and sure was glad to get it. We always want to hear from home and in my case from California where I hope to spend my days after this “cruel war” is over. I have seen a few of the places you advised me to look up…What a great people are the French. And what a history they have. I turn now to the present. I wish you could see the big dally papers, over here, compared with the dally papers of American cities, they are but toys, I know something about papers, for you know I served an apprenticeship on the Los Angeles Times. That is a great paper.

Mark Twain did not overlook the barber when he visited over in Europe. His account of the barber and the barber shop is good. He gave a funny experience as the readers of Innocents Abroad will attest. I will tell you my experience. Entering the shop I was conducted to a chair — I mean a barber’s chair by a highly uniformed porter. 1 thought He was a major-general. The shaving seems to be a family affair. A kid of twelve or fourteen years lathers your face and he does not skip any part, not even the eyes or mouth. Another kid rubs the lather well in, then comes Agamemnon, the barber himself, razor in hand and he does the work. You sit flat in the chair, feet hanging down to the floor at a right angle from the knees. No lounging with feet elevated and resting on a soft vervet cushion as in America.

I must tell you something about the war – the censor may strike it out, but I will try it. Listen, Germany will be beaten to a frazzle inside of a year. I have talked to too many prisoners not to know what I am talking about. They were always hungry and wanted peace. You would hardly believe your eyes if you could see our boys almost fighting to get on to the front line. They want a lick at the Huns, let me tell you, and let me say to you, don’t talk peace. I don’t want peace until our boys nail the American flag on the door of the Hun capital and they will do it and don’t you forget it.

– Press Democrat, July 16 1918

MANY BREEZY NOTES TAKEN FROM ‘THE SPIDER’ IN FRANCE

From Paul Stevens, a Sonoma county boy with the Engineers in France, The Press Democrat has received another issue of “The Spider,” a monthly paper published by the Engineers and which is full of interesting and breezy notes of the life of the soldier “over there.”

Readers of The Press Democrat will be interested in a few of the excerpts taken from “The Spider.” Here is a writeup of a dance:

Chic French Girls “Rag” at E Company’s Dance

American ragtime, Southern melodies by the colored boys, French comedy and American comedy, solos and quartettes. Jugglers and fireaters. jig dancers and ballet dancers, marked the entertainment April 17, near E Company headquarters, under auspices of the Jazz Orchestra. And afterward everyone danced.

E Company was out for an orderly good time. The air vibrated music from the lightest passing two step to “The Rosary.” In front of the hall a line of autos, coupled with brilliant lighting effect, reminded one of a miniature Broadway, while the courtyard, overhung with decorated lanterns and springtime decorations, was a “petite promenade.”

At the dance some were dancing American steps and others French. “But the overseas steps prevailed, for what is a French maiden to do when all pieces are ragtime, and her partner is a burly railroader intent on putting over his schedule of “Bunny Hug” and “Boston Dip?” At that everyone enjoyed it. Including the small Yvonnes and Jeans who, with the older Messieurs and Mesdames, had only come as onlookers. The whole village turned out, and the French folks outnumbered the Americans.

While the floor was cleared for the dance, sandwiches and coffee were served in an arbor.

Here’s some more:

Breakfast In France

The American idea of breakfast is something new to the French. They don’t have “breakfast” in France; they have “dejeuners.” But they don’t have dejeuners until 11 o’clock. Until recently it was a familiar sight in most any French town to see Americans, early in the morning, roaming around desperately looking for a place to eat.

Then some enterprising French restaurant keepers found out the Yankees eat as much at 7 a. m. as they do at 7 p. m. Catering to the new allles’ sun-up appetites they displayed stiffly formal cards: ” Breakfast Served.” And then, ” Eggs and Ham.”

[..]

It Was Too Bad

In a village near which a portion of A Company is located, three Frenchmen went forth to serenade their lady loves not many nights ago. One had an accordeon, another a bass drum, and the third a bugle. They rendered several selections under the windows of each of the three “maisons” which they hope some day to win, while the appreciate demoiselle, in each case threw down a bouquet to her favored lover.

Rumor has it that some sort of an American game was going on not far from the place where the concert took place. The exact nature of this game has not been determined, but it is said that little cubes, speckled with round dots were shaken up in a box and tossed upon a table, while copper and silver discs were exchanged by the players from time to time with such exclamations as “Come on, you seven!” and Here’s where I have to walk home!”

It was 8:15 by the clock, but the players had lost all track of time.

Suddenly the first notes of taps came floating upon the evening air. There was a wild scramble, the five American soldiers broke the half mile record back to camp. They burst into their Company hut, only to find the lights burning. The usual evening activities were in full swing, and there was no sign of preparations to retire.

And then from somewhere in the village was borne the oft-cursed sound of reveille. This was followed in rapid succession by “recall,” “call to quarters,” “overcoats,” “payday,” ”retreat” and “fatigue.” The French trumpeter was serenading his lady love with American bugle calls…

– Press Democrat, July 17 1918

MISS CONSTANCE COOKE WRITES OF AIRMEN RAIDS

An interesting letter has been received from Miss Constance Cooke from the war in France. Speaking of the reports of her devotion to duty during the raids on the hospital by German airmen, Miss Cooke says:

“I was very sorry such newspaper reports got into San Francisco papers. It seems the correspondents are keen on exciting the home folks. Many instances, however, come to our notice which are certainly worthy of being known by the public.

“Of course, those successive nights of bombing were rather hard on one’s nerves, but it is ‘c’est la guerre,’ as the French say, and everyone in the war zone expects these things. We deserve no credit. We just happened to be on duty, and stuck to our job, as 99 out of a hundred would do anywhere – 100 out of 100 here; for all of the Americans over here have the one purpose, to stop at nothing which will help win this war,

“The French are glad and proud to have the Americans in the trenches with them, and our boys are certainly doing big things at present. I am proud of them.

“On the Fourth of July there were celebrations all over France to honor the Independence Day of America. You know the French are great for ‘frills’ and fetes. Their preparations in the various hospitals for the benefit of the American nurses and patients were really touching. Decorations were made from the wild red poppy, bachelor buttons anf marguerites.

“There was quite a celebration in the town square. French and American flags were flying everywhere the eye turned. Captain J—- was a little worried that the boche might give us another raid and break up the party, and we expected an offensive at the front. But there was no raid and our boys gained more of the enemy’s lines that day.

“The fete of July 14th is at hand and we plan to return the cordiality of the French as far as possible.

“You would smile If you could see me now with a tiny night lamp, shaded very carefully, straining my eyes to write.

“I think I wrote you about being changed from my ward of American boys, after their departure, to a newly opened ward with twenty Frenchmen. As soon as they were evacuated, I was put on special day duty for one week with a pneumonia case (a boy fron Oklahoma) in a French hospital. As soon as the boy was well enough to get along with an aid, I returned to our Red Cross hospital and took back my original ward. There were only seven patients, but within a day or so there were twenty-seven.

“On the 3d of July, Dr.——-, who has charge of those of us who first came to B——, took Miss Joaquim and me in his machine out to C——, a little village about six miles from the Somme front. Beyond this town a short distance, is located a French hospital for gassed cases. There are seven or eight American nurses and aids on duty there. Dr. C. and Chaplain L. had been invited to a dinner and Miss Joaquim and I had dinner with the nurses. Later we were shown through the entire hospital. It was a tent hospital, i. e. some ten or twelve long tents and two brick buildings – accommodating about three or four hundred patients. It was all extremely interesting to me after the work I had done in B, with the same sort of cases.

“On July 4th, Dr. ——- obtained special permission for fifteen nurses and aids from several different villages to go to C—–, close to the front, where the 1st Engineers are stationed. The officers had planned a barbecue and had sent us earnest invitations to be present. At the work was not so heavy at the time, we were mighty glad of the opportunity to out so close to the trenches. We did not go into the trenches, but were very near to the reserve trenches. On the way out we saw many instances of the use of camouflage and also miles and miles of barbed wire defenses.

“It was quiet in that particular sector so we heard only one or two cannon blasts. Just beyond Field Hospital No. —— we came to a stretch of woods and going around to the rear of them we came upon extensive fields, where the 1st Engineers were stationed. There were hundreds of men in uniform. We arrived in the midst of a boxing and wrestling matches and a vaudeville show by some of the men, also orchestra numbers. At 5:15 all faced the flag floating above and sang our national hymn. Then folowed mess call and retreat.

“They had arranged a long table out under an old apple tree, where we fifteen American women together with fifteen of the luckiest (?) among the officers sat down to ’slum.’ I had heard of ‘slum’ many times from the presented with a huge plate of it – (something like our Irish stew) meat potatoes, vegetables and gravy. We were served on a various assortment of plates, salvaged from evacuated homes. After the dinner we danced for two hours in a tent with a board and canvas floor fixed for the occasion. The men certainly enjoyed having us — said it was their only social in a year. Of course we were glad to be there, too, and enjoyed it immensely.

“As the ward has again been evacuated of 26 patients. I have been put on night duty for three nights at a French hospital. Have only seven patients. Pneumonia, lung and other bronchial affections.

“Miss Gilbert, one of my roommates and I are to return to Paris Thursday a. m. Of course I am rather loth [sic] to leave but feel the new experience may be worth while. Expect a return to children’s service or to be transferred to the military service.

– Press Democrat, August 16 1918

ENGLISH FOOD NOT GOOD AS FURNISHED BY THE U. S.

French Wines Do Not Appeal to One Youth

Santa Rosan Tells Interesting Story of Trip and Describes Scenes Älong Route — Has First Taste of Wine and the French Hospitality — Language and Customs Strange, Yet All Are Enjoying Life and Good Health While Preparing for Active Work of War.

A letter from Corporal Ernest L. Richards of Co. E, 316th Am. Train, A E. F., to a former schoolmate, gives a most graphic account of the trials and joys of the trip from camp to France. It will he read with interest by his friends as well as others…

…Through all the country that we had traveled, we saw many old-fashioned contrivances and buildings, and the people, and the machinery and methods of all kinds of living and working. The people dressed very old fashioned, wore wooden shoes, lived in very peculiar shaped houses, built of stone, which were mortared up with clay or dirt. Some of the American boys could talk the lingo, but most of us had to listed to the peculiar noises and be satisfied. Good water was plentiful in most places, but most prevalent of all was the historic French wine.

A quart bottle of wine was cheaper than a quart bottle of water. The price of a quart bottle of wine varied in the different parts of the country through which we passed, but the equivalent of 26 cents American money would purchase the finest bottle of Port Wine or Claret ever made. This is the point at which I fell, and although I never thought I would indulge in liquor, I took my first drink of liquor from a French wine bottle. There is indeed a very peculiar taste to the stuff and although most of the boys would make a quart bottle bubble almost all of its entire contents away, I could in no way see the enjoyment. Many bottles of wine were drunk on the train before our journey was completed, but it was owing to the fact that any other kind of refreshments were impossible to get. Fruit, bread and candy, and in fact any other kind of luxuries were unseen. All this time we were living on hard tack and canned corned beef (horse). Could you blame us refined fellows from the west for bold indulgence of accepting a drink of French wine?

Upon our arrival here we were billeted to different parts of the village wherever accommodations permitted, and at least we had a good, hard floor to stretch out on, and plenty of good, home made American coffee, white bread, cheese, etc., and such like. The first meal we had in our own quarters and you can just bet it was greatly appreciated and enjoyed by all. Our teeth were as yet mighty sore from eating the hard tack, and it seemed mighty good to get something more tasty to chew on for a while.

This village is almost directly south of Paris, and if anything, a little east. This village is about 600 years old — as quaint and old as many of the other little villages that we saw during our travels. We are about 14 miles from a fair sized town by the name of Clare – a fair sized town. The French people are indeed very intelligent and interesting in every way. They are indeed very anxious to learn English as well as to teach the American soldier boys French. I have been out to several French homes to learn French and lots of fun we had, and certainly see some very new and peculiar things.

Every home is well supplied with wine, which the people consider a great treat and courtesy to offer to their visitors when they come to see them. I was not in any way fond of the different shades of the red liquid that was offered me, nor could I understand what they were speaking of, but it was given with such hearty good will that one could not help but accept it. None of the boys will ever forget the hearty welcome we received from these innocent, old fashioned people. Although we cannot converse, we feel the hearty welcome by their customs and actions and courteous manner of treatment toward us, and they try so hard to explain things to us. Many of the boys have been taken into private homes and given real honest to God feeds, but as yet such has not been my pleasure….

– Press Democrat, August 27 1918

CENSORED LETTER FROM ARTILLERYMAN ED KOFORD

Former Santa Rosan Now in France Writes Entertainingly of Life in That Country and Some of the Ancient Cities, But Information Is Cut Out as of Military Value to the Enemy.

Edward Koford, a graduate of the Santa Rosa high school and well-known resident of this city, who enlisted in the regulars shortly after the outbreak of the war, is now in France…

…“After a few days in England we crossed over to France – the battlefield of the nations. We are at present billeted in a very antique village. Its early history dates back to the time of the Romans and Saracens. The height of glory for this place was in the days of chivalry. There still exist many ancient gates and sentry lookouts along with a very intricate system of underground caverns. The boys are learning French rapidly, for we are living in actual contact with the people. (At first the oui, oui, Monsieur, sounded more like wee, wee, manure.)

“The American army abroad is no longer petite. In nearly every city, town and hamlet are to be found American soldiers on duty. Wherever American troops are quartered there may also be found a Y. M. C. A. hut. The Y. M. C. A. is rendering an inestimable service to the boys abroad. We have found the French people very hospitable. Their charming manners, politeness, generosity and cheerfulness have won the hearts of American soldiers. These people are and have been sacrificing such as you people at home will probably never have to do. Vive, Vive la France!

[..]

Yours in arms, “Edw. Koford.”

– Press Democrat, August 28 1918

LIEUTENANT E. E. CAMPBELL WRITES OF EXPERIENCES

Son of Mr. and Mrs. Geo. R. Campbell, of Santa Rosa, Now in France With 364th Regiment of Infantry, Tells of His Arrival and the Sights and Scenes He Is Enjoying Overseas.

July 28, 1918

Dearest Mother: -Here at last is a Sunday with plenty of time to myself, so I guess you’re in for a long letter… It was two o’clock in the morning before we finally arrived, and then after that it didn’t take very long to be assigned to our billets. Lieut Tooze and I are together in a room with the deputy mayor. It’s certainly a wonderful room too. Typically French – marble fire place, marble topped hand carved table, and one of those funny French beds. You know, mother, that a Frenchman has peculiar ideas of what a bed should be like. He builds it far too narrow for two people, about four feet high, and a person is supposed to lie on one feather bed and cover up with another one. I most suffocated the first night I slept in one, so I put up my own cot in the room and let Tooze have the bed. My cot is only 16 inches high, and poor Madame le Deputie couldn’t understand how in the world I could sleep on such a thing. When I came in last night I found that she had put a chair under each leg so that it would be high enough, according to her ideas of a bed.

From our room we get a wonderful view of Monsieur’s garden. It’s just like the French gardens that we used to see in the movies – white stone wall with red tile tops on them, roses and all kinds of flowers, and beautiful climbing vines everywhere. It really doesn’t seem true.

We are in a wonderful little village. Before the war it had a population of 117, but out of that 25 have been killed, and all of the other young men are at the front, and all of the young women are away working in the munition factories, so there are only a few old people and children left here. All of the houses are of white stone with either red tile or shale rock roofs. There is a little stream of water running through the village where the men can swim and wash their clothes. Ordinarily water is scarce in this country.

I nearly forgot to tell you about the town crier. In this place a newspaper is practically unknown, and whenever anything happens a funny little old gent goes along the streets beating an old drum and shouting out the news. It Is the funniest thing I ever saw, but at that we have got to be careful and not crack a smile for it is an old, old time-honored custom, and we must respect it, too…

…It’s surprising how we can get along with these people and make them understand us. Not a one that speaks a word of English, but we talk by using a mixture of English. French, Spanish, German, hands, feet, ears and eyebrows. But really I’ve picked up more French here in three days than I did in two months at Camp Lewis…

– Press Democrat, August 31 1918

WONDERFUL PRIVILEGE TO HELP IN THE HOSPITALS

Miss Constance Cooke, Daughter of F. W. Cooke of Healdsburg, a Red Cross Nurse in France, Declares Her Part Nothing Compared to the Work of the Soldiers.

Miss Marguerite Snook received an interesting letter from Miss Constance Cooke, Red Cross nurse in France, a few days ago, and from which the following extracts are taken:

I am writing on the date of the fourth anniversary of this awful war. I can remember very well when it was declared. I was in Berkeley for the summer session of 1914. Suddenly one day extras came out with entire pages filled with the beginning of the struggle. The news was dreadful and unbelievable. For the past few weeks now our papers here have had good reports. It does begin to look as though peace were not far distant. We were so happy yesterday to learn of Soissons being regained.

My! you should see some of those towns which have been subjected to bombardments and later been invaded by wanton troops. I can’t imagine a sadder picture, except, perhaps, the ruins of the fine old cathedrals, some of which have been standing for centuries.

The big observation balloons are’almost constantly over us nights and in the daytime we have often watched the maneuvers of the French planes doing all sorts of acrobatic stunts on high. Also, we have seen the Boche planes, which came over us on clear days to get pictures, being chased by the French aviators. These day air battles are exciting to watch. As a rule the machines are too high to see but we can hear their guns plainly and see the smoke from them – like small, fluffy white clouds.

The men in the First Division, which arrived in France on June 26th, last year, are almost entirely easterners and southerners. So far they have done most of the fighting and we have cared for very few wounded out of the more recent divisions. I don’t believe I have met a dozen Californians since coming over.

I was sorry to hear of Fred Cummings’ death. Too bad! He was so young, and had so much to live for yet.

Goodness! I was provoked about those reporters sending news of the bombing raids. I wrote Julius Alexander and told him the sentiments were beautiful in the poem dedicated to me, and that I would try to do something worthy of them before leaving France.

It’s very nice to have people proud of you, but it’s really uncalled for in my case. I am only one of thousands of Americans in the service abroad, and we realize fully that those at home are all sacrificing and doing everything in their power to help Uncle Sam. Why, we who are over here are enjoying the work, day by day, and feel it a wonderful privilege to be helping in the hospitals. It is our thousands of American boys in the trenches and under shell fire daily that we should be proud of. They are the heroes of the day.

You should hear some of their experiences. When I read the encouraging letters they write home, my heart just aches for the boy and his family as well. I’m quite content that some mothers aren’t conscious of what their sons are going through, for it wouldn’t help matters any.

I have only five patients tonight, the others having been evacuated. One is a gas case and another has T. B. Both will have to be returned to the United States, as they are unfit for further active service. Another boy of twenty is from Ohio. He has a shrapnel wound in his back. Although operated upon, they were unable to extract one piece, which lodged in a vertebra. He also has two other shrapnel wounds and a machine gun bullet whizzed through his blouse without even touching him.

He gave me a Boche ring, and when I asked ”Was he dead?” he answered: “Dead?—-Well, I had to put on a gas mask to go near him.”

This boy is in the marines, but has been over the top three times – at Catingy, Belleau Woods and Soissons. He assures me that next time he will get a German Iron Cross to send me.

My fourth son is from Florida – a very attractive boy of nineteen, who graduated from high school last year. He has a hole through his left hand, made by a machine gun bullet, several of the bones being fractured also. We keep the wound irrigated constantly by means of a rubber Dakin tube and solution. He suffers from shell shock, and it is pitiful to see him — he is delirious half of the time — living over again those hours of the battle. I have written to his mother, who has two other sons over here in the First Division.

When men are wounded or gassed, official notice is sent to their nearest relatives. I often write to the mothers, sisters or sweethearts of the patients, because it naturally makes the home folks feel easier to get word directly from the hospital wards. Often the boys do not feel one bit like writing even if they are able. Patient No. 5 is a Canadian man.

Last night Fritz paid us a short visit. No bombs were dropped. This was the first night air raid in seven weeks.

Tonight they came at 11 and stayed until 12:30. It sounded pretty exciting – bombs were dropped somewhere within close range. We were reminded at once of old times.

It is perfectly amazing to see what a big part the American Red Cross organization is playing in France. It seems there isn’t a thing done in which they don’t lend a hand. I have had a good chance to see how much is done by them for the wounded and hospital patients and also I know how much the boys appreciate it all. It seems their resources are unlimited. I often think of the millions of dollars it must cost to keep up this huge business of theirs – and then simultaneously somes the thought of the campaigns, driven and parades in America — of the knitting and surgical dressing circles — and then I realize that there can be scarcely an individual of mature age who is not giving until it hurts – as they say.

If there are no other benefits from the war – this I am sure of – it will have drawn individuals of nations closer together on account of necessity of sacrifice and giving common to all.

It is rather nice to have my present small ward of patients, for I have more of a chance to “baby” them. All of the nurses feel the same way, and you would, too. No matter how “mangy” they are – and some of them are pretty much so – we love them.

– Press Democrat, September 6 1918

BRUCE BAILEY TELLS OF WAR EXPERIENCE IN FRANCE

BRUCE BAILEY has written Jas. W. Ramage a very interesting letter from France in which he tells of a number of thrilling experiences and of meeting a number of Santa Rosa boys. His many friends here will be glad to read this letter, which is as follows:

Oct. 3, 1918…

…We left our position at the front some ten or twelve days ago and marched to this sector. Our marching was done at night, averaging about twenty-five miles each night, and as this was kept up for five nights it was very tiring. Not to let us get stale on the job, the last two days they marched us from noon till the next morning, and it was on these hikes that we did cover some ground.

I was a mounted man, but just before starting on this trip my horse went lame and I was forced to lead her for four nights. We passed a French horse hospital and I turned her in to this place, and I am glad that I did, for a horse leads a very hard life. It is hard enough on a man, but a horse fares far worse than a man. During this operation the red tape connected with getting rid of my horse was left way behind the column. While trying to catch up with the regiment I passed an aviation camp and found that Harold Bruner was there, so stopped and found him. The pleasure of seeing one another was equally, mutual as it had been a long time since I saw anyone from home and to see such a close friend I can assure you I was entirely compensated for the delay it caused me and the fact that I missed any rest that night.

Harold is a sergeant in the wireless detail of this aero squadron. In endeavoring to catch up with my regiment, I jumped a truck. I never saw saw so much traffic on a road or street in all my life. Artillery, cavalry, trucks, troops, ambulances, etc., going and coming. Finally the truck I was riding on managed to worm its way through and we arrived up where they were having a lot of excitement. Shells of all descriptions. From a currier [sic] I found out that my outfit had turned into the woods some four kilometers back, so believe me, when I tell you it did not take me long to find an empty truck running to the rear. I found the regiment near morning and We have been here ever since.

Two days after we received orders to pack and be able to move in two hours, and we have been waiting ever since for further orders. As things are moving along very nicely for the Allies on this sector, we are being held in reserve about eight kilometers from the front, this about five miles. The guns have been pounding away. It is getting late in the year and we are experiencing wane very very disagreeable weather. It is cold and rainy, and it is nothlg to sleep in wet clothes and wet blankets. Of course, cleanliness is a thing of the past, as water is very scarce to wash or drink. I haven’t had my clothes off in about fifteen days at night. During our march we stopped in an old French billet, and here I picked up some sort of vermin. They were not “cooties” but I had to burn my clothes, and fortunately I had some more to put on. It is rather an exception to have any extra clothes. The fellows leave them behind as it is so inconvenient to wash them, but I foresaw this, and have held on to all the clothes that I could. I do not think it is necessary to state when the men bathe, but you have heard of all those stories about the farmers who are so unacquainted with water; something on that order.

We are being fed very well, considering the conditions under which we exist. Of course we consume great quantities of corned “Willie,” but if a man gets hungry enough he will eat most anything. During the march we ate corned beef and hard tack all the trip and it became very tiresome. Sweets are the things we miss most, but it can’t be overcome. Canteens are very scarce and I had a hard time getting this paper to write to you on. I might explain how I have the use of this typewriter. It was wrapped up in one of my blankets on the end of one of our wagons, so I borrowed it. One runs out of everything here but patience…

…As you understand there is no one from home of California with me in this outfit and as I have charge of or rather am the top sergeant of this detachment of seventy men, I am about as popular as a Hun in Paris. I have a difficult job, hut I am making the best I can out of it.

This is our third trip to the front and I have had many interesting and dangerous experiences to relate, but I will not take up your time with them now…All of us are having the experience of a lifetime, but dodging shrapnel, high explosive shells, wearing gas masks and all those things are experiences one can get along very well without…

Very sincerely, F. Bruce Bailey, American Ex. Forces, A. P. O. No. 742.

– Press Democrat, November 7 1918

COMSTOCK TELLS OF SANTA ROSANS

Interesting Letter From Major, Who Left Here as Captain of Co. E, Now an Instructor in France, Giving an Account of Many Boys From Here.

A stirring letter has been received from Major Hilliard Comstock of Santa Rosa. who is in training in France. The letter is as follows;

France, Oct. 14. 1918.

Dear H.:— I told you in a previous letter that I lost my trip to the front by being ill in bed with Spanish influenza, did I not? Yesterday I had a most interesting trip. A lieutenant, formerly of my battalion, and an officer of our old National Guard, who had been transferred among the many others to a front-line battalion, telephoned over to a friend at one division headquarters that he had been wounded and was in the hospital not many kilometers from us and wouid like to see some of us if we could get over to visit him. Many officers of our regiment have made the supreme sacrifice already. Some killed — many more wounded. You understand that my present job is the training of troops for the front line divisions and I am not at the front myself, but the largest part of our outfit has been sent to the front. Both officers and men have been in many severe actions already. Well, to return to my story, — it is wonderful how one’s heart goes out to a comrade, who has “been in” and “made good. I would rather have made this trip over to see Bill H—. than to have done anything I know of.

Right here and now, dear H—, I am going to say. I shall never again judge a man by his personal habits and completely condemn him for having a few bad ones. At the same time I do not wish to sanction them. I hold my ideals about personal cleanliness as high as ever, but I will hereafter and through my life be able to love the good qualities in even those men with whom I would not wish to associate while they do some things that they sometimes do. This lieutenant was a rather unprepossessing looking fellow and could be called somewhat wild. He drank some and smoked a lot — liked to “see life” and all that, but I can love him from now on for what he did in the battle line at Verdon, in our recent drive on that sector. We — myself and another — got on a train which took us to a rather large city not far from here, and quite near to the hospital where Bill was. The train moved so slowly, as all French trains do now (any old time they feel like, and never run on, schedule) that we didn’t get to the city until evening — so we decided to go out in the morning to the enormous new hospital where Bill was. We stayed all night at a hotel and in the morning, just as we were about to go for our breakfast, who should we run plump into on the street but Bill himself, looking quite pale, but feeling fine and cheerful. His wound was from a rifle bullet (German sniper). He was shot squarely through the top button of his uniform, the bullet entering the top of his right lung and ranging down and out under his right arm. It fell inside his clothes, where it came out. He has both the button and the bullet, as well as the trench map of the sector on which his battalion attacked. The map is all covered with blood. As extreme good luck would have it, he had no bones broken and no arteries severed. The wound was a clean one and healed quickly, so he is well and walking around now, though suffering some inconvenience from the wound. His story is very interesting. He described the German machine gun fire as very intense after the Americans had lost their artillery barrage. His battalion had advanced quite a bit more rapidly than those on its flanks, so that the Germans made it awfully hot from the flanks for awhile. His platoon was badly shot up at one stage and had broken loose and run. A big shell burst near him and be found himself whimpering and crying from the shock and excitement. He was in cover in a shell hole, but realized that if he stayed there his nerve was gone, so he forced himself out into the fight again. During the fight he twice traveled back forth with information. But here was the best thing he did. His platoon had advanced right up by the side of a machine gun position. There the boche was in the act of swinging his gun to open fire on the flank of his platoon. With a lucky aim from his pistol he shot the gunner straight through the neck, killing him instantly. For this he was mentioned in orders for bravery in action. This will give him a promotion. It is maintained by the colonel that bravery is only an officer’s duty — thus be does not receive the distinguished service order.

C. P. has been up on the line for quite a while. He is in a division from which I get no news. I pray God that nothing has happened to him. He is a good officer and a fine fellow. Gee! but it would hurt if anything were to happen to him.

F. C. was ordered up to the line on our return. He left this morning. There is another fine boy! I hope he comes through all right. Your letters come regularly now — I hope you get all mine.

FURTHER DETAILS GIVEN

Another letter from Major Comstock. reciting some of the facts, has been received by Dr. D. H. Leppo of this city, and parts of it not in repetition of the letter previously given, are reproduced herewith:

“I know you will be interested to hear the news of some of the boys. Don Geary is here with our regiment, still and so is Burton Cochrane. Both have excellent records as officers. We are a training unit and every little while we send a large number of officers and men to the line. Over half of our old officers and men have gone most of them in the San Mihiel or Verdun sectors. Our officers have made wonderful records. In fact, all of the men who were in the old original regiment have made good in action. Reports have come to us repeatedly of the good state of training that both officers and men from our organization were in.

“It is remarkable what escapes some men have. Lieut. Wm. Hayes Hammond. a nephew of John Hayes Hammond, and an officer formerly in my battalion in a Fresno company, went through the most thrilling engagement last week, when we took the Montfaucan vicinity. He was wounded in a place where, if the bullet had been an eighth of an inch to one side or the other, he would have been killed. As it is, he is already out of the hospital and feeling finely.

“At one stage, with his platoon, he attacked a whole company of Germans, scattered them and delivered a whole platoon of American prisoners whom the Germans were making off with. When he was wounded and had gotten first aid from one of his corporals, two stretcher bearers started to carry him to the rear and a machine gun opened fire on them; the bearers dropped him and ran; he rolled from the stretcher to cover, but before he get out of range several bullets had passed completely through his gas mask, which was hanging on his chest. Isn’t this a thrilling tale? He was mentioned in orders and a promotion for it, with possibly a distinguished service cross.

“Out of three officers who went up from my battalion to the line, all three have been wounded; this one whom I have told you about by a rifle bullet, another with H. E. shell fragments, and the third gassed. A sad case was that of Lieut. Carleton Adams of San Rafael, who has been reported killed. He was married in San Diego the day I was, a week before we left. He was a corporal in the San Rafael company at the Mexican border and won his commission last spring at the same time as Chauncey Peterson and Bill Bagley got theirs. Chauncey Peterson has been up in the line for some time, but I have not heard from him. Frank. Churchill left this morning to go up.

“Nearly every member of old E Company who was anywhere near officer material and who had the border experience has won his commission. Most of them have made fine officers. The National Guard divisions have the best reputation over here. The old regular army was all broken up by so many of its officers being promoted to high commands and so many non-coms getting commissions. The National Army has shown inexperience in many cases. The fact that a National Ouard division at Chateau Thierry ‘showed up’ a regular division is said to be responsible for us all being classified as U. S. Army now without distinction.”

– Press Democrat, November 13 1918

MAJOR HILLIARD COMSTOCK WRITES FROM WAR THEATRE

From Major Hilliard Comstock who commands a machine gun battalion, Judge Thomas C. Denny has received a very interesting letter, telling of some of his experiences in the great battle that has been fought overseas. The letter from the Santa Rosa officer follows:

On Active Service with the American Expeditionary Force, Nov. 3 1918

Dear Judge: I often think of you and I can hardly realize that it has been nearly two years since I have had anything to do in your court. I do not regret it, however, for this war is the greatest cause men ever fought in, and the most wonderful experience any one could ever have.

I have had the bad luck to be kept in the rear areas most of the time as an instructor. It seems too bad that they have put this onto most of us who have had the greatest amount of experience. It has been also the lot of Major Dickson of Petaluma, and many others who have followed the military game longer than most of those who are now in it. We have sent thousands of men into the line, and a great many officers, and they have made a wonderful record. The officers of our old California, organizations, particularly, have won great reputations. They have had some awfully tough fighting. Some of them were with Major Whittlesley in the tough scrap in the Argonne Forest, and lots of them have been in the St. Mihiel and Verdun sectors. They have paid dearly for it, though. Out of seven officers whom I sent from my battalion I got news of five, and two of these five were killed and the other three wounded within one month of the time they went up.

We are now at last in a forward area and have a chance to get into the line soon, if the Boche doesn’t lay down his arms too quickly. I have the word of one who can do it that he will send me into the line the first they have need for a major, so I have hopes.

Have not seen anything of Finlaw Geary since he came to France. The Grizzlies are not near us, and I do not know where they are.

I have seen a lot of Donald Geary. He is doing finely and is much liked by all of his brother officers. The last I saw of him was when he was leaving for a school of instruction a month ago. The regiment has changed stations since then, and I heard he had been ordered up to the line, and that he will not return to our organization, but I don’t know how true it is. Nearly all of the boys from Santa Rosa who were in my old company and who have since been commissioned, have either been transfered to some other regiment behind the lines or have been sent up to the front. I hear very little of them.

We are near a large city on what was a short time ago the front. Imagine a city the size of Oakland simply shot to pieces? That is this city. It gives one a strange feeling to see a city like this destroyed and deserted, but now the population is streaming back and business is started again, despite the fact “Jerry” can fly over and drop a few tons of bombs when he wants.

Best regards to you, Judge. It may not be long now before we are home again.

Hilliard Comstock. Major 159th Infantry. American E. F., France.

– Press Democrat, December 3 1918

Like other breweries across the country, the beer-making section of big plant at the foot of Second street in Santa Rosa was ordered shut down by government regulation. The given reason was the nationwide shortage of coal, which began after the U.S. entered WWI; at the time coal was the fuel that ran almost everything in the country and while the crisis had little impact on the West Coast, the situation in the Eastern states was dire. William Jennings Bryan came to Santa Rosa and told us six million tons of coal a year were wasted on brewing beer; that was almost double the true figure, but it didn’t matter that he got it wrong because he sounded so convincing, as he always did.1

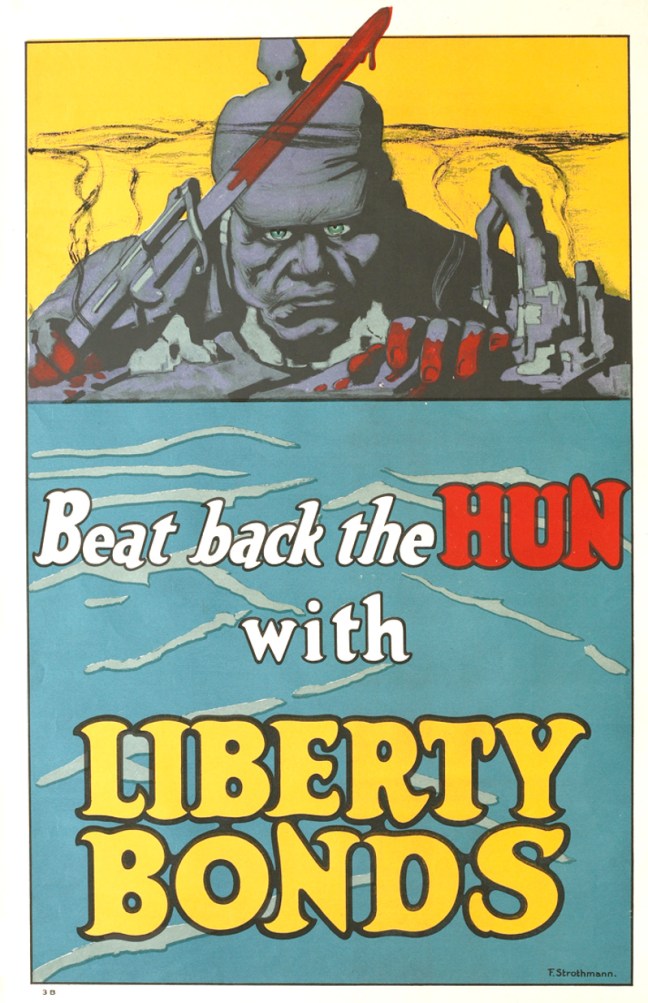

Like other breweries across the country, the beer-making section of big plant at the foot of Second street in Santa Rosa was ordered shut down by government regulation. The given reason was the nationwide shortage of coal, which began after the U.S. entered WWI; at the time coal was the fuel that ran almost everything in the country and while the crisis had little impact on the West Coast, the situation in the Eastern states was dire. William Jennings Bryan came to Santa Rosa and told us six million tons of coal a year were wasted on brewing beer; that was almost double the true figure, but it didn’t matter that he got it wrong because he sounded so convincing, as he always did.1 There were also several movies about espionage in the U.S. in 1918, most notably “The Prussian Cur,” described as a docudrama that was a “mighty panorama of the war…reveal[ing] the menace of the German spy system in America.” The film included scenes of an Allied soldier being crucified by Germans. With its heavy-handed Christian symbolism, posters were also made of German soldier performing crucifixions, as shown below. The story was certainly a myth; the victim was first supposed to be British, then Canadian, and it was never clear where and when it supposedly happened.

There were also several movies about espionage in the U.S. in 1918, most notably “The Prussian Cur,” described as a docudrama that was a “mighty panorama of the war…reveal[ing] the menace of the German spy system in America.” The film included scenes of an Allied soldier being crucified by Germans. With its heavy-handed Christian symbolism, posters were also made of German soldier performing crucifixions, as shown below. The story was certainly a myth; the victim was first supposed to be British, then Canadian, and it was never clear where and when it supposedly happened.