Spoiler alert: This may be the craziest thing you’ll ever read and stranger still, its author was one of the most notable men ever to live in Santa Rosa.

(Above: Detail of Aviation magazine cover, April 1910, slightly modified)

“Santa Rosa in the Year Three Thousand–Looking Back Ten Centuries” appeared in the Press Democrat a few weeks before Christmas, 1913 and is transcribed below. Here’s a summary of what he predicted:

Around the year 1925 Sonoma county built a canal connecting the Russian river to the Petaluma river, through the Laguna, Mark West and Santa Rosa creeks. It was big enough to handle the largest ocean steamships which was a good thing because about 2700 the entire Pacific ocean seabed rose up in the “great upheaval” and capped the Golden Gate. All of this new land became part of the United States (of course) and all commerce and travel with Asia went through the Sonoma canal to the mighty river that formed and stretched all the way to China. By then, Santa Rosa was not only a major seaport but when the Queen of the East visited here as a guest of the Santa Rosa Improvement Club she declared it a great and beautiful city. An election was held in 2905 and Santa Rosa was chosen as the nation’s new capitol, to be built on Taylor mountain after it was graded down to an elevated plateau.

The great legacy of the early 1900s lived on. On the capitol grounds was a statue of Luther Burbank, the renowned scientist who revolutionized the vegetable and plant life. A mathematician at Sweet’s business college, one of the leading institutions of the country, invented a new form of math or physics or something.

A great Santa Rosa scientist discovered it was light, not gravitational forces that binds the universe together. Engineers were able to harness the mysterious, invisible force emanating from the sun and soon everyone was flying around in a light powered “palada,” which could travel nearly the speed of light. A Santa Rosa adventurer tried to go to the moon in a palada, but failing he made the journey around the world. He was gone about three days.

It’s difficult to know what to make of this. Edward Bellamy’s 1888 novel “Looking Backward” was a great success and created a new genre of fiction mixed with philosophy for predicting the future, as found in the dozens of books and articles which appeared in following years asserting human culture would become extremely utopian or dystopian if some current trend(s) continued. In those cases, the authors were always were trying to drive home a specific idea; here, there’s no point at all except “yay, Santa Rosa,” maybe. These future histories are also great opportunities for biting wit, commenting on the “backward” present day conditions; you can comb through all 1,800 words in this essay and not fear being bitten, unless one counts the passing observation it took until the year 2950 for Santa Rosa to create a public park.

Keeping a scorecard of the prediction accuracy in these early examples of science fiction is always fun. No, there was never a canal built between the Russian and Petaluma rivers, but there was talk the previous year of cutting a channel through the Laguna (see following article). Here the author did get solar power right (sort of) and may have been inspired by a presentation in Santa Rosa a few years earlier that demonstrated gee-whiz gadgetry including a little motor powered by a photovoltaic cell. That lecture was also in the form of a look back from the future, titled “In the Year 2000.”

No, instead of those serious works, this essay more resembles the Sunday newspaper cartoons of the day such as The Kin-Der-Kids or Little Nemo, where silly and fantastical things happen for no particular reason. Nemo’s Slumberland even likewise had a queen and the story of the guy who was sidetracked on his way to the moon sounds exactly like a plot from those funny pages – although sans cartoons, there’s nothing particularly amusing about someone changing course.

So who wrote this not-funny comic scenario and pointless future history?

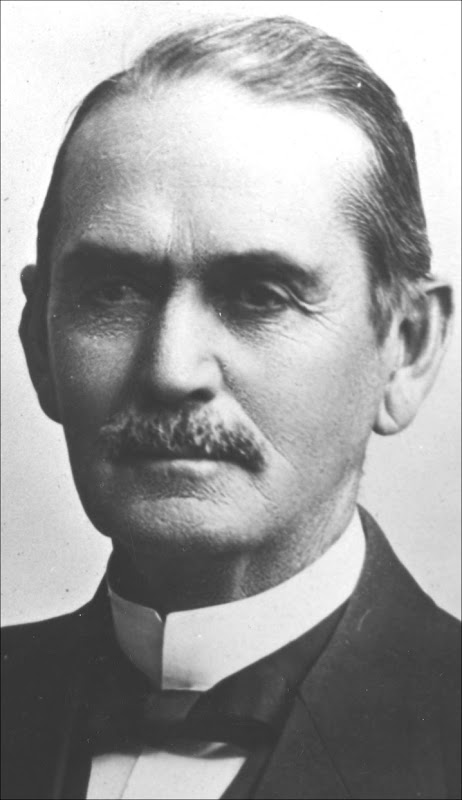

The author was John Tyler Campbell, who was a big deal in Santa Rosa almost from the moment he arrived about 140 years ago. He was elected city attorney a year later, in 1875, and also became the county’s assistant D.A. He ran for the state assembly as a member of the “New Constitution party” – a small and short-lived political group that vowed full support of the controversial new state constitution which was narrowly approved in 1879. He served two terms in the assembly, being speaker of the house for part of that time.

Next came a diplomatic career; he was off to New Zealand to become the American consul, followed by appointment as consul to the Chinese cities of Fuzhou and Tientsin. In an unusual arrangement with the U. S. government, he also served as consul for Germany while in China. Back in America in the 1890s he lectured about China and the Chinese people; it would be interesting to learn what he thought, as the state constitution he once ardently supported was in large part meant to deny the Chinese who were here their basic rights.

Although he was usually referred to as “Judge Campbell” no history shows he actually presided over any court in California (his son was a Sonoma County Superior Court judge, however). He served on the committees that framed two city charters for Santa Rosa: 1876 and 1904, joined in the later one by his friend James Wyatt Oates – Campbell attended the Oates’ housewarming party (at what would become known as Comstock House) in 1905, then a decade later was an honorary pallbearer at Oates’ funeral. They were both respected attorneys but out of step with Santa Rosa’s lingering pro-Confederacy, “Old South” political leanings. Campbell, who grew up in the slave-holding part of Missouri, rushed to join the Union at the outbreak of the Civil War and rose to the rank of captain.

Campbell often contributed stories to magazines and newspapers according to profiles in the county histories, although this is the only one currently found. In 1906 he completed writing a book about dueling (!) but the manuscript, along with his other papers, were destroyed in his downtown office during the great earthquake and fire.

One wonders why the Press Democrat agreed to publish this odd essay when it could only serve to damage Campbell’s esteemed name. It appears unedited; the nutty ending about the Queen of the East and paragraphs about Atlantis and the Tower of Babel were apropos of nothing and should have been red-penciled out. The typeset article was clearly not proofread as it is rife with typos, which was unusual for the PD. Perhaps editor Ernest Finley, who could nurse a grudge for decades, disliked Campbell as much as he hated his friend Oates and was glad for the chance to embarrass the old man. Campbell was 73 when this essay was published and lived until 1935, dying at 94.

MIDDLE: Detail of 1912 portrait of John Tyler Campbell, courtesy Sonoma County Library

BOTTOM: Detail of 1902 drawing by Albert Robida predicting the year 2000

The year two thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine is gliding away and will take its place with the past. It soon will be numbered with the things that were “a schoolboy’s tale, the wander of the hour.”

The year three thousand is near the door and Father Time will introduce her to the coming ages. She will be received with happy smiles and glorious expectations. At the threshold of the coming year let us recount some of the most striking events of the past ages.

The year three thousand is near the door and Father Time will introduce her to the coming ages. She will be received with happy smiles and glorious expectations. At the threshold of the coming year let us recount some of the most striking events of the past ages.

The confusion of tongues at the Tower of Babel, as recorded in the Book of Books, gave to the world the varied languages used by the human race. At the time it came suddenly and without warning, and it is difficult to full realize the great confusion and entanglement that came to the workers on the great tower.

Away back in the dim past the continent of Atlantis was suddenly engulfed, completely swallowed up and became lost to the world. Then in its place appeared the Atlantic ocean. Milton wrote “Paradise Lost” but he afterwards wrote “Paradise Regained,” a similitude for the lost continent Atlantis was followed by a continent regained in the Pacific ocean. Less than three hundred years ago a great upheaval occurred in the Pacific ocean and a new continent was thrown up along the west coast of North America, and it extended out westerly in the Pacific ocean more than two thousand miles, but it became contiguous territory attached to the west side of the continent of North America, and after these years it cannot be determined where the old land ends and the new continent begins. The upheaval that gave to the United States and so it remains to this day.

Following the upheaval the progress of the country surpassed all dreams and all expectations. River of the old continent forced themselves over the new territory and out to the Pacific ocean. Fruits and vegetation and in fact all products of the soil, grew in the greatest profusion and the greatest abundance. The horn of plenty poured its wealth out in the new territory. Immigration flocked in from all over the world and soon great cities, towns, and villages sprung up everywhere. Mills and factories were constantly in motion and the hand of industry brought in a constant stream of gold. In the hundred years following the acquisition of the new land America had more wealth than all Europe put together. The population far exceeded all Europe. About this time the name “United States of America” was changed to “Columbia.” This was done in honor of the great discoverer, and it is the name it should have had all the time.

The capital of the country had always been in Washington City, but it became in time far from the center of population. So about the year two thousand nine hundred and five Congress submitted the question of the removal of the capital to a vote of the people. A number of well located and populous cities entered the race, but when the election was over and the votes were counted it was found that Santa Rosa, California, had won the capital. People who had given the matter consideration were not surprised. At the time of the voting Santa Rosa had become one of the largest and most attractive cities in the world. Its population was nearly a million.

Away back to about the year nineteen hundred and twenty-five, the County of Sonoma constructed a canal from the mouth of [the] Russian river, through Russian river, the Laguna, Mark West and Santa Rosa creeks, thence on to Petaluma creek, thus connecting the waters of the ocean through to San Francisco bay, and the largest ocean steamers passed through the canal. The canal was a simple matter for nature had almost made it, and it required but little extra work to send the waters of the ocean through Sonoma county.

When the great upheaval came and closed up the [Golden Gate] the Sacramento river passed its way through Petaluma creek and through the Sonoma county canal out to where was once the Pacific ocean, and thence it continued to cut its way through the new-made ground of the new continent to the Pacific ocean, now well over to China. The commerce of the world entered the Sacramento river at its mouth near the continent of Asia, and in time came to be one of the greatest and most important rivers in the world.

Santa Rosa has been the capital of the republic for nearly a hundred years. In all of these years it has been the county seat of Sonoma county, and its importance as one of the great cities of the world is a sufficient justification for giving some of the leading events of its history.

Back in the twentieth century Santa Rosa was the home of the renowned scientist, Luther Burbank, conspicuous in history as the man who revolutionized the vegetable and plant life. He not only changed existing products of the soil and doubled their size, but he greatly increased the variety and quantity of the necessaries and luxuries of life. His productions were superior to any ever known before, and hence they were eagerly sought for by the people over the world. It is impossible to overestimate the great benefit realized by humanity from the Burbank productions. His statue has a conspicuous place in the great hall of fame in the capital grounds in this city.

The theory that motion counteracts the laws of gravity and keeps the heavily bodies in their orbits in the revolutions had always been accepted as true. The law of gravitation is the tendency of all bodies toward the center of the earth. If motion were to cease the bodies obeying the law of gravity would all fall together in a crash. About fifty years ago Prof. Herr von de Reido of Santa Rosa, after long investigation, made the assertion that light and not motion kept the heavily bodies in their orbits–that light counteracted the law of gravity. It was twenty-five years before his discovery was accepted as true.

The theory that motion counteracts the laws of gravity and keeps the heavily bodies in their orbits in the revolutions had always been accepted as true. The law of gravitation is the tendency of all bodies toward the center of the earth. If motion were to cease the bodies obeying the law of gravity would all fall together in a crash. About fifty years ago Prof. Herr von de Reido of Santa Rosa, after long investigation, made the assertion that light and not motion kept the heavily bodies in their orbits–that light counteracted the law of gravity. It was twenty-five years before his discovery was accepted as true.

The sun is the center of the universe and there is a mysterious, invisible force emanating from the sun, and by the means of machinery and appliances this force is now conserved and used in propelling airships and other contrivances used for transportation. The palada is the vehicle for transportation of people or freight now in general use, and the motor power that propels it is light. Travel is now almost entirely in the air, and the palada is made for one person or for any number of persons. It is easily set in motion and its speed can be increased almost to the velocity of light. It is also used for freighting and for running all kinds of machinery.

In the days of Jules Verne, Phineas Fogg went around the world in eighty days. Hans Patrick Le Conor of Santa Rosa, filled with adventure, tried to go to the moon in a palada, but failing he made the journey around the world. He was gone about three days.

When Santa Rosa won the capitol, Taylor mountain was selected as its site. The capital grounds contain one thousand acres and were graded down to an elevated plateau by machinery propelled by the power of light, and the work was done in the short space of thirty days. Under the old system it would have required ten years.

The grounds are ornamented with the Burbank productions and are the most beautiful in the world. They surpass in grandeur and loveliness the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon. The capitol is the most picturesque building in the world.

The universe is too vast for the humanmind to grasp, or to comprehend. There are stars so far away from the earth that it would take a million years for them to reach the earth even if they traveled with the velocity of light, which is one hundred and ninety-two thousand miles per second. An eminent astronomer had published that the rays of light from the star Nova Geronimo started to the earth the same year that the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, Massachusetts, in sixteen hundred and ten, and although they had been over three hundred years speeding toward the earth they have not reached their destination, and the problem as to the length of time required was considered in the well known commercial college established by Prof. J. S. Sweet of Santa Rosa, then as it is now, one of the leading institution of the country. One of the students in the college, Alamon del Marsoni, a born mathematician, undertook to figure out the problem, but after many months of constant work he gave up, but he made a new discovery in figures, and with the new principle which he had worked out he was enabled in a few minutes to give the true answer to the problem. Under the new theory any problem of mathematical question can be unerringly worked out with one-tenth the figures and in one-tenth of the time required under the old system. The new theory is now universally accepted.

The fame of Santa Rosa as a great and beautiful city spread over the world, and people of taste and culture came from everywhere to see it.

The Queen of the East, the lineal successor of the Queen of Sheba of King Solomon’s time, was one of the number who came to the great and beautiful city of Santa Rosa, and she viewed the city and gave forth the following words: “It was indeed a true report which I heard in mine own land. Howbeit, I believed not the words until I came and mine eyes had seen it and behold, the half was not told me.”

The queen while in Santa Rosa was the guest of the Santa Rosa Improvement Club, the oldest club in the State, having had a continuous existence for more than a thousand years, and during a great part of that time had faithfully and diligently worked for a public park in Santa Rosa, and fifty years ago victory crowned their long, faithful service. They actually acquired the park and dedicated it to the city forever.

The Queen of the East said goodbye to the thousands of people who gathered about her, and in a moment of time she and her train of paladas disappeared over the Sierras and were lost to view.

The world is nearer perfection tan ever before. It has been one hundred and fifty years since the last war, and when it closed the gates of Mars were shut and they have remained closed ever since. The reign of the Prince of Peace is universal and eternal.