In Sonoma county, the most important outcome of election day 1912 wasn’t who would become president; it was whether voters would kill the roadhouses.

Before launching into this topic, I need to offer a mea culpa; a few articles here regarding the year 1912 are being updated. Accuracy is important (or should be) to anyone who cares about history, and events that happened around New Year 1913 shine a different light on some earlier stories. My small consolation is those late developments even caught local newspapers by surprise, as you’ll read below.

In June 1912, voters in the unincorporated parts of the second district elected to go “dry” (the second district was then a north-south strip west of the Laguna, from the Russian River to Petaluma). Saloons were still allowed in the towns of Sebastopol and Petaluma but country roadhouses were forced to close, or at least stop serving alcohol. While the temperance movement was locally gathering steam in 1912 and 1913, both Santa Rosa newspapers expected the law to pass because roadhouses were harming property values and reducing productivity of farmworkers.

There were only about a dozen places in rural West County impacted by the closures, but the roadhouse scene was expanding closer to the county’s more urban areas. It’s not hard to understand why; more people had cars to escape the city, roads were being improved for autos, and towns (particularly Petaluma) were discouraging – and even banning – dancing to popular music. At the country roadhouse, anything goes.

Churches loudly condemned the roadhouses but community leaders only wrung hands. The Press Democrat lamented, “The number of saloons and road-houses in the Sonoma valley is out of all reason. No self-respecting community could be expected to continue forever to put up with conditions such as exist there.” As a speaker in a series of talks called “What’s the Matter with Santa Rosa?,” attorney Thomas J. Butts complained the town was not growing as fast as it could “because of our surrounding roadhouses.”

But as 1912 rolled on, nearly every week brought stories in the Bay Area papers about serious accidents, even deaths, because of roadhouse drunks “joy riding.” Women were found to be drinking in public (horrors!) and some were prostitutes who were arrested. And on July 1, the governor of Oregon declared martial law as a platoon of cops laid siege to a pair of particularly notorious roadhouses outside Portland. Increasingly counties around the state were banning roadhouses.

Thus it was no great surprise to read the announcement of an “Anti-Roadhouse League” being formed here to get an item on the November ballot calling for prohibition throughout all parts of the unincorporated county. “The league is formed solely for the purpose of eliminating the road houses from the county,” read the statement in the Santa Rosa Republican, “and is not dominated by any religious sect or temperance organization, and does not propose to interfere with licenses now held by hotels or summer resorts now in business or which may hereafter desire a retail license.” This was the text of the proposed ordinance:

No person, corporation, firm or association shall sell, or engage in the business of selling, offering for sale or giving away distilled, fermented, malt, vinous or other spiritous or intoxicating liquors or wines or beers in any portion of Sonoma county lying without the corporate limits of any city or town of said Sonoma county, except such person, corporation, firm or association engaged in the business of conducting a bona fide hotel, having at least thirty-five separate sleeping apartments properly furnished for the accommodation of guests, and having dining room at which meals are served at regular hours to boarders and the traveling public. |

That was at the end of August. Over the next two months before the vote, I can’t find a single op/ed in either Santa Rosa paper concerning the proposal, pro or con. Make of that what you will; my interpretation is that they didn’t think it had a chance in hell of passage. Unlike the earlier second district vote where ballots were cast only by those who lived within the affected rural areas, this was to be decided at a high-profile, November election where every voter in the county could have a say. And the city folk liked saloons (or at least the menfolk, who were allowed to drink inside, did).

Surprise! The ordinance passed easily – thirteen points, 56 to 43. All of the towns voted for it by a comfortable margin including Santa Rosa.

But actually that was only the first surprise; no one knew how to implement the new law, or whether it was really legal. A few days later, the Press Democrat offered an article headlined, “ANTI-ROAD HOUSE ELECTION NOW HELD TO BE INVALID.” The Presiding Justice of the Appeals Court said it violated the “local option” law, where only a community could choose to make itself “wet” or “dry,” as happened in the earlier second district vote. Towns had no say on the matter; Petaluma voters, for example, couldn’t set the rules for distant Geyserville.

“The anti-roadhouse ordinance, carried at the election held in Sonoma county a week ago last Tuesday, is null and void,” the PD declared, “there is no doubt whatever but that the election in this county on the matter is invalid.” There were still no op/eds on the matter in either Santa Rosa paper, which is why I was lulled into presuming this really was not a Big Deal.

District Attorney Clarence Lea filed two complaints to test the ordinance in Superior Court. One was against Everett N. Ellsworth, who had a commonplace roadhouse just two blocks north of Santa Rosa city limits at the corner of Mendocino and Carr avenues, right across from today’s SRJC. (Obl. Comstock House connection: A few years later, John A. Comstock, the divorced husband of Nellie and father of Hilliard Comstock et. al. would live in this house as a border with the Fisk family.)

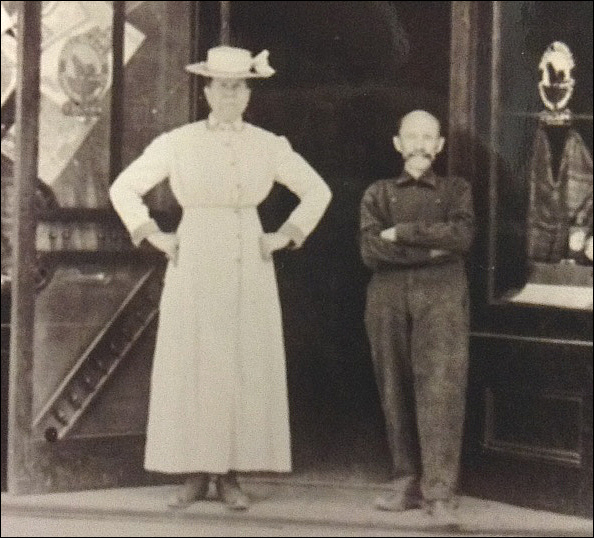

The other suit was against John D’Arcy Connolly, an Irishman who had been on the Board of Supervisors in the 1880s and served as U.S. Consul in Auckland for eight years in the 1890s. Connolly owned the Hotel Altamont in Occidental, which was the nexus of West County social life.

(RIGHT: Hotel Altamont in Occidental, c. 1914. J. D. Connolly is to the right of man in white shirt and vest. Photo courtesy Sonoma County Library)

(RIGHT: Hotel Altamont in Occidental, c. 1914. J. D. Connolly is to the right of man in white shirt and vest. Photo courtesy Sonoma County Library)

The Hotel Altamont was a challenge to a very particular part of the ordinance, requiring a place to be a “bona fide hotel, having at least thirty-five separate sleeping apartments properly furnished for the accommodation of guests, and having dining room at which meals are served at regular hours.” The Altamont qualified in every way – except it did not quite have the 35 guest rooms required. One has to believe the Anti-Roadhouse League chose that very precise, arbitrary number because they knew no place had that many beds.

A week before Christmas, the Connolly case was presented to Superior Court Judge Denny in a courtroom packed with an audience representing both sides. Denny ruled in favor of the ordinance immediately after arguments in order to expedite it proceeding to the California Supreme Court.

Confusion reigned. Most (all?) liquor licenses were to expire in just a few days, on January 1. The Board of Supervisors had stated no licenses would be issued “until the courts have passed upon the validity” of the ordinance. Since the matter was still headed to the State Supreme Court, was the law in effect or not?

District Attorney Clarence F. Lea declared on Dec. 28 that the ordinance would be followed. No new liquor licenses for roadhouses. No alcohol to be served after midnight on New Year’s Eve anywhere outside of a handful of towns in the central part of the county. D.A. Lea would have been reckless if he didn’t request a police guard that night.

All of this is prelude to the fallout in the following year, which will unfold in the following item. It’s the wildest political story I’ve encountered for Sonoma county – emotions ran high on both sides. I’ll close with this teaser: Six days into the new year, the Board met to consider the “injury being done to the legitimate business in the county.” This was followed by a motion granting liquor licenses to fourteen country saloons who had filed affidavits with the county clerk swearing their hotels indeed have the required 35 rooms. One of the licenses went to J. D. Connolly – apparently he somehow discovered over the Christmas holidays the Altamont had enough rooms after all, and the Supervisors were more than happy to take his word for it.