Petaluma was soooo lucky. Mark Twain, that funny guy everyone was buzzing about, made only a few appearances before he left for the East Coast and Europe, probably never to return out west. Reviewers had been giddy with delight over his recent appearance in San Francisco: “From the beginning to the end, the interest was never allowed to flag,” gushed the Chronicle. “Taking it altogether, ‘Mark Twain’s lecture may be pronounced one of the greatest successes of the season.” Other SF newspapers sang with similar praise. Thus on November 26, 1866, you can bet Hinshaw’s Hall was crowded with Petalumans expecting to spend a jolly evening. Spoiler alert: They hated him.

The next edition of the Petaluma Journal and Argus offered a review of his lecture with the headline, “REPREHENSIBLE.” That fellow who called himself Mark Twain was a complete flop (“…as a lecturer he falls below mediocrity”) and the San Francisco papers should be condemned for misleading the public by giving good reviews to such bad entertainers.

Now, wait a minute; today, everyone knows Sam Clemens/Mark Twain was the most celebrated speaker of his time, if not all of American history. Surely that Petaluma critic was as much an idiot as the Hollywood producer who supposedly dissed Fred Astaire’s screen test, “can’t sing, can’t act, balding, can dance a little.”

As it turns out, the Petaluma review was truthful, albeit inartfully written (the full review is transcribed below, apparently for the first time since 1866). Evidence found in contemporary papers show Twain’s appearances in those weeks were often stinkers – and it seems he was aware of that but did not know how to improve. Following one lecture he told a friend he felt like he was a fraud who was taking people in.

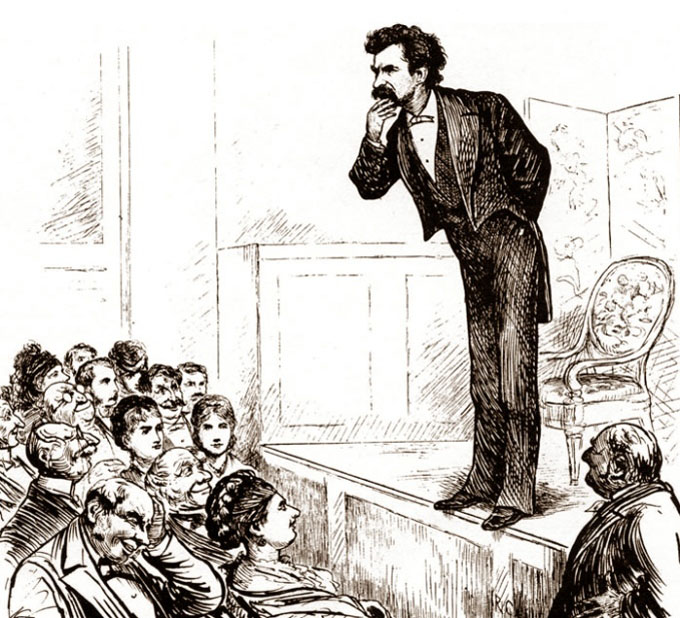

But that’s not the story he tells in his memoir and first popular book, Roughing It, or when reminiscing as he did in his remarks about stage fright made after his daughter’s musical recital. In his version, he was nervous about his debut performance in San Francisco, fearful that no tickets would sell and no one would laugh at his jokes. He papered the house to pack it with friends including three “giants in stature, cordial by nature, and stormy-voiced” who were expected to howl with glee and beat their shillelagh on the floor whenever Twain made a funny. Still, he was terrified of failure. From Roughing It:

…before I well knew what I was about, I was in the middle of the stage, staring at a sea of faces, bewildered by the fierce glare of the lights, and quaking in every limb with a terror that seemed like to take my life away. The house was full, aisles and all! The tumult in my heart and brain and legs continued a full minute before I could gain any command over myself. Then I recognized the charity and the friendliness in the faces before me, and little by little my fright melted away, and I began to talk. Within three or four minutes I was comfortable, and even content. My three chief allies, with three auxiliaries, were on hand, in the parquette, all sitting together, all armed with bludgeons, and all ready to make an onslaught upon the feeblest joke that might show its head. And whenever a joke did fall, their bludgeons came down and their faces seemed to split from ear to ear… |

“All the papers were kind in the morning,” Twain finished up, referring to those reviews the Petaluma paper later called “reprehensible.” As he didn’t write about his subsequent appearances, Gentle Reader was left with the impression all went smoothly after his debut butterflies. And as far as I can tell Twain biographers all take him at his word, speeding past events of that autumn to arrive without delay at his rise to international fame.

It’s a great shame more attention hasn’t been given to this period, as this was a turning point in his life. “Without means and without employment,” as he wrote in Roughing It, he convinced himself public speaking was his “saving scheme,” despite having absolutely no experience or training at it. And although the reviews after his debut were often poor, his convictions seemingly never faltered that he would now do this for a living. If nothing else, it’s an inspiring story of determination; constructing a Mark Twain from scratch was not easy work.

The topic of Twain’s lectures were the “Sandwich Islands,” AKA the Kingdom of Hawaii, where he had just spent five months as a special correspondent for the Sacramento Daily Union. The Kingdom was a pretty exotic place to Americans in 1866 and the couple of dozen articles he wrote were well received, but travelogue lectures are not where you usually expect an evening of knee-slappin’ humor. Twain destroyed his copy of the speech years later so we don’t know exactly what he said, but from snippets and summaries we know the lecture was mainly a travel description of people, places and things along with his wry observations. Or as the Sacramento Union critic wrote, he “seasoned a large dish of genuine information with spicy anecdote.”

The topic of Twain’s lectures were the “Sandwich Islands,” AKA the Kingdom of Hawaii, where he had just spent five months as a special correspondent for the Sacramento Daily Union. The Kingdom was a pretty exotic place to Americans in 1866 and the couple of dozen articles he wrote were well received, but travelogue lectures are not where you usually expect an evening of knee-slappin’ humor. Twain destroyed his copy of the speech years later so we don’t know exactly what he said, but from snippets and summaries we know the lecture was mainly a travel description of people, places and things along with his wry observations. Or as the Sacramento Union critic wrote, he “seasoned a large dish of genuine information with spicy anecdote.”

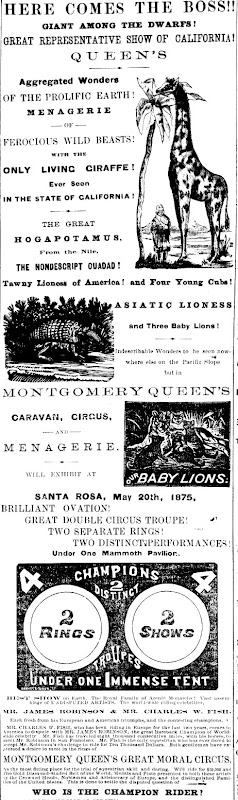

The advertisements he placed in the papers became celebrated in their own right. Shown here is his first from the Sept. 30 Daily Alta California (CLICK or TAP to enlarge) with its funny blurbs. “A SPLENDID ORCHESTRA Is in town but has not been engaged“, read one of them. At other lectures he came up with different items, such as “THE WONDERFUL COW WITH SIX LEGS! Is not attached to this Menagerie“. Most famous was the tag at the end: “Doors open at 7 o’clock. The Trouble to begin at 8 o’clock.” He varied this line, too; another example was, “Doors open at 7; the inspiration will begin to gush at 8.”

Once back in his old Gold Country stomping grounds, he also ran this in the Nevada Transcript and Grass Valley Union:

After the lecture is over, the lecturer will perform the following wonderful feats of SLIGHT OF HAND, if desired to do so: At a given signal. he will go out with any gentleman and take a drink. If desired, he will repeat this unique and interesting feat – repeat it until the audience are satisfied that there is no deception about it. At a moment’s warning he will depart out of town and leave his hotel bill unsettled. He has performed this ludicrous trick many hundreds of times in San Francisco and elsewhere, and it has always elicited the most enthusiastic comments.At any hour of the night, after ten, the lecturer will go through any house in the city, no matter how dark it may be, and take an inventory of its contents, and not miss as many of the articles as the owner will in the morning. The lecturer declines to specify any more of his miraculous feats at present, for fear of getting the police too much interested in his circus. |

The Mark Twain who appeared on stages in those weeks was more or less an imitation of his contemporary and friend who went by the name of Artemus Ward. One of the most popular humorists during the Civil War – Lincoln opened the cabinet meeting about the Emancipation Proclamation by reading aloud a little humor sketch – Ward’s stage persona was a backcountry hick who drawled through rambling stories, clueless there was anything remotely funny about his remarks. Audiences ate it up. It was Ward’s great success that undoubtedly inspired Twain to try his hand at it.

Those early lectures by Twain included a great deal of clowning. He would open by pretending he did not know there was an audience; if there was a piano available the curtain sometimes went up with him yowling and banging away at an old saloon tune, “I Had an Old Horse Whose Name Was Methusalem.” From a good profile of Twain’s years in the West, “Lighting Out for the Territory:”

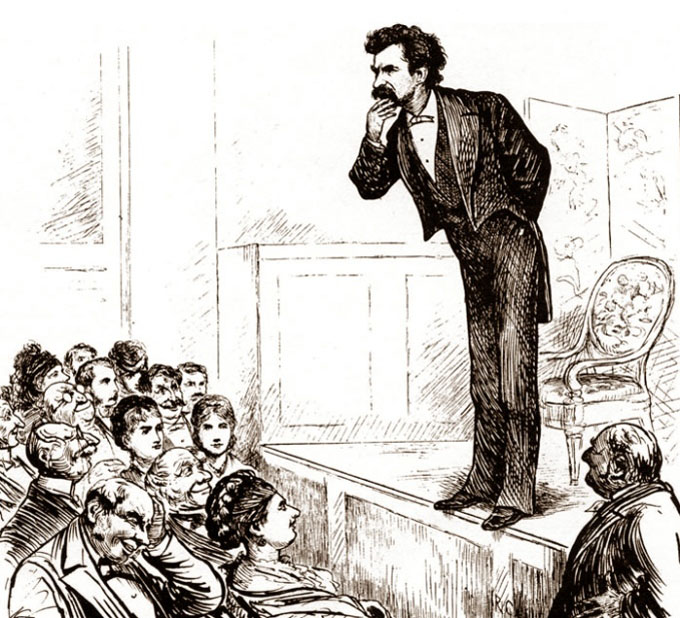

As can best be reconstructed, he simply sauntered onto the stage from the wings, his hands stuffed into his pockets and a sheaf of papers clutched under his arm. He wandered vaguely around the lectern for a bit, looking for the most comfortable place to stand, and then appeared to notice the audience for the first time, the expression on his face registering an equal mixture of surprise, perplexity, and fear. For a long moment he looked silently at the audience while it looked back at him, waiting.

|

Once he introduced himself the comic shtick continued as he pretended to be shocked and mystified whenever there was laughter or applause. Describing his debut performance, a journalist in the audience recalled “…the apparently painful effort with which he framed his sentences, and above all, the surprise that spread over his face when the audience roared with delight or rapturously applauded…”

His Petaluma review was certainly the worst. but other reactions were decidedly mixed. Even as the Chronicle called his debut “one of the greatest successes of the season,” the back page of the same edition had a little item about running into Twain on Montgomery street and telling him “the envious and jealous” were saying it wasn’t worth the price of admission. When he appeared in San Jose the Mercury said “the lecture was entirely successful” while the Santa Clara Argus wrote “the lecture disappointed.” For his second San Francisco lecture the Chronicle called his performance unpolished and raw: “Some of ‘Mark’s'” jokes were very much strained, and others were so nearly improper–not to say coarse–that they could not be heartily laughed at by ladies.”

This was not harsh criticism, but that any were negative has to be weighed with understanding he had a “favorite son multiplier.” Samuel Clemens was a fellow newspaperman and drinking buddy of everyone in the City and in the Sierras who reviewed his appearances. They all wanted him to succeed, if for no other reason that he used his box office receipts to buy rounds of drinks after the show.

So great was his popularity that the harsh Petaluma review received its own smackdown from the Grass Valley Union:

Unfortunate Clemens! Why did you blight your lecturing prospects by attempting to pass the ordeal of the corn and spud-producers of the Russian river country? You may do in San Francisco and ‘sich like places,’ but you ought to have known better than to brave the Petaluma lions in their den…what business had you, Mark Twain, up in that part of the country? Telegraph to the St. Louis and Cincinnati Boards of Commerce that you cannot accept their invitations to lecture – that your lecturing star went down in Petaluma. |

We have that sublime gob of sneer thanks to Santa Rosa’s newspaper, the Sonoma Democrat, where editor Thomas L. Thompson was still locked in battle with the Petaluma Argus over the Civil War, by then over a year and a half. (In an adjacent article, the Confederacy-mourning Thompson ranted at length about “the Radical tools and dupes of Abolition despotism.”) Thompson was clearly delighted that another editor handed him a cudgel to bash Petaluma and he did so with relish, taunting their critic as not “able to appreciate the entertainment” and comparing him to a dimwitted character in a Shakespearean play.

By the end of 1866 Mark Twain was on a ship headed to the East Coast. Over the next seven years he would deliver the Hawaii lecture some 150 times, by his count, almost always to acclaim. How did he completely turn it around?

For starters, he must have sharpened his focus once he was facing audiences of strangers and not his personal acquaintances, as was the case in California and Nevada. In the second Chronicle review they noted his weeks performing in front of his old pals in the Gold Country had changed his performance and not for the better: “…He was a little too familiar with his audiences. What will be thought very funny by the inhabitants of the desolated wastes on the other side of the Sierra Nevada mountains, won’t do at all in great metropolis like San Francisco.”

He also likely improved the writing; the Hawaii lecture he gave in 1873 probably was very much evolved from the original of 1866. His early reviews remarked at how much information he packed in about the climate, volcanoes, weird food, “board surfing” and the native people who were primitive because they did not act or dress like Victorian-era Americans. That didn’t leave much time for humor beyond making witty asides; were people filling his theater seats for a geography lesson or to have some laughs?

An incident during the Nevada leg of his tour should have given him cause to reflect: While walking the short distance back to Virginia City after an appearance at a mining town, Twain was held up by masked robbers who took his money and expensive gold watch. It soon came out the highwaymen were really his friends playing a prank and everything was returned to him, but Twain was livid and unforgiving. Why did they do it? Some forty years later, one of would-be brigands revealed they hoped it would cause him to stick around Virginia City and give another talk. And hopefully for that lecture, the robbery – which they had made as scary as possible – would be his topic instead of rehashing those damned factoids about Sandwich Islands.

But it appears his biggest improvement was dropping the stage business – the silly gimcrackery of pretending he had no idea what he was doing in front of an audience. He became less targeted on checking off the list of Hawaii’s wonders than sitting back and telling us a story about the place. Here was the emergence of the beloved Mark Twain we all know (well, the Hal Holbrook we all know), the man in the white suit, relaxed in the comfy chair and flicking ashes off his cigar while keeping us spellbound with whatever fool thing that happened to pop to mind. Volcanoes? Jumping frogs? Steamboats and your Missouri childhood? Whatever, Mark, just keep talking. We’ll listen to anything you have to say. You never needed the theatrics.

|

| Unknown illustration, probably from early edition of Roughing It |

“Mark Twain’s” Consolation

Meeting “Mark” this morning on Montgomery street, the following dialogue ensued:

“Mark” — Well, what do they say about my lecture?

We–Why, the envious and jealous say it was “a bilk” and a “sell.”

“Mark” — All right. It’s a free country. Everybody has a right to his opinion, if he is an ass. Upon the whole, it’s a pretty even thing. They have the consolation of abusing me, and I have the consolation of slapping my pocket hearing their money jingle. They have their opinions, and I have their dollars. I’m satisfied.

– San Francisco Dramatic Chronicle, October 3, 1866

SECOND LECTURE BY “MARK TWAIN”-Platt’s Hall has been engaged for to-morrow by “Mark Twain,” tor the delivery of his second lecture on the Sandwich Islands, and in addition he promises “the only true and reliable history of the late revolting highway robbery, perpetrated on the lecturer at the dead of night between the cities of Gold Hill and Virginia.” The tickets for the lecture are for sale at the book stores, “The wisdom will begin to flow at 8.” “Mark” will depart on the steamer of Monday, for a visit to the Atlantic States.

– Daily Alta California, November 15, 1866

…”Mark” was not as happy in this new lecture as he was in his old one. He was not in very good condition, having of course got alkalied while in the savage wilds of Washoe, and at the same time we fear that he had become a little demoralized. He was a little too familiar with his audiences. What will be thought very funny by the inhabitants of the desolated wastes on the other side of the Sierra Nevada mountains, won’t do at all in great metropolis like San Francisco. Some of “Mark’s” jokes were very much strained, and others were so nearly improper–not to say coarse–that they could not be heartily laughed at by ladies. However, “Mark,” of course, sent the audience into fits of laughing again and again; and as a whole, his lecture was thoroughly enjoyed by those present. “Mark’s” travels to the interior, where he has so many friends, have not improved his style. The lecture which he delivered last night might have been polished considerably without wearing down any of the sharp points with which it was ornamented.

– San Francisco Dramatic Chronicle, November 17, 1866

“Mark Twain,” the Missionary. styled the “Inimitable.” by the Mercury, favored a large and appreciative audience at San Jose, on Thursday, with an amusing account of what he heard, saw, and “part of which he was,” in the Sandwich lslands. One attraction, he announced, was necessarily omitted. In illustration of Cannibalism, as practiced anciently, he proposed to devour, in presence of the audience, any young and tender cherub if its maternal parent would stand such sacrifice for public edification, but there being no spare infants at hand the illustration was not given. With this exception, the Mercury says the lecture was entirely successful. They want him to do it again.

– Daily Alta California, November 24, 1866

The Argus, concerning ” Mark Twain’s” lecture, says: We have long been an admirer of the infutitable humor of the lecturer, as shown in his numerous letters and sketches that have been so widely published but confess that the lecture disappointed us. We expected to hear the Kanakas “joked blind,” but had no idea of being treated to such an intellectual feast as he served up to his audience. We never heard or read anything half so beautiful as his descriptions when he laid aside the role of the humorist and gave rein to his fancy. To use the expressions of a wrapt listener to the lecture, “he’s lightnin’.”

– Daily Alta California, November 25, 1866

MARK TWAIN.– The Alta of Sunday last says that Mark Twain is to deliver a lecture in this city Friday evening. We hope this is not a mistake.

– Petaluma Journal and Argus, November 22, 1866

REPREHENSIBLE.– The gentleman who enjoys a wide celebrity on this Coast as a spicy writer, over the non de plume of “Mark Twain,” delivered his lecture on the Sandwich Islands, in this city, on Monday evening last. While we accord to him the merit of being a spicy writer, candor compels us to say that as a lecturer he is not a success. We say this through no desire to be captious, but simply because it is literally true. As a newspaper correspondent Mark Twain is a racy and humorous writer, but as a lecturer he falls below mediocrity. In this connection we think it not inappropriate to address ourself to the editorial fraternity on this Coast, and to our San Francisco contemporaries in particular, in relation to the reprehensible practice of disguising the truth in reference to the qualifications and ability of persons who sell their talents for a valuable consideration, and too frequently “sell” those who go to hear them, innocently expecting to be instructed or amused. To remedy these evils we must begin at the fountain head. San Francisco occupies that proud eminence, and what she has of intelligence and real worth we delight to honor. She possesses an array of talent and varied accomplishments of which she may justly be proud; but her journals have apparently yet to learn to discriminate between stars of the first and ninth magnitude. They seem to lack the power of discrimination, and bespatter with printer’s ink all aspirants for public fame, without any seeming regard to their fitness or ability to meet the requirements of the public. Through their fulsome praise the public expectation, in the interior, is worked up to the highest pitch of expectation, and as a consequence nine times out of ten is doomed to disappointment. These frequent dampers upon public expectation has rendered the people so suspicious that lecturers of real merit are frequently mortified by finding themselves facing an audience that would be a discredit to the attractions of a hand organ.

– Petaluma Journal and Argus, November 29, 1866

POKING FUN AT PETALUMA.— The ridiculous comments of the Journal and Argus upon “Mark Twain’s” lecture in Petaluma, which we noticed at the time, have called forth some pretty sharp remarks from various quarters. The Grass Valley Union lets off steam in this manner: “Unfortunate Clemens! Why did you blight your lecturing prospects by attempting to pass the ordeal of the corn and spud-producers of the Russian river country? You may do in San Francisco and “sich like places,” but you ought to have known better than to brave the Petaluma lions in their den. What Mud Springs was to the Californian who crushed a certain young lady’s musical aspirations with a few well directed word-shots, silencing the match-making parent forever, Petaluma is in a lecturing way. Have not the Petalumans had Lisle Lester and other lecturing and reading stars up their way, and what business had you, Mark Twain, up in that part of the country? Telegraph to the St. Louis and Cincinnati Boards of Commerce that you cannot accept their invitations to lecture—-that your lecturing star went down in Petaluma.” There is a mistake here, through which injustice has been done to the people of our neighboring town. They had no fault to find with “Mark Twain.” On the contrary, his humorous and instructive lecture was highly appreciated by them. The editor of the Journal and Argus is the dissatisfied individual on whom Clemens wasted his wit. Not being able to appreciate the entertainment, he at once pronounced “Mark Twain” a failure. Evidently, when doing so, in the opinion of the press of the State, he followed the example of Dogberry of old, and displayed his ears rather prominently.

– Sonoma Democrat, December 22, 1866

Read More