Imagine asking someone in the Bay Area anytime around the turn of the last century to “Name someone who lives in Santa Rosa.” There’s little doubt that first pick would be that guy named Burbank. But depending upon the year, a surprising number of people might have thought of Blitz W. Paxton. Unlike Burbank, he wasn’t famous because of personal achievements; he was well known because he was often mentioned in the newspapers on account of being sued – and he was sued a lot.

The saga of Blitz (and yes, that was his real name) is a pretty good story in its own right, but it’s really all background to the article which will follow, describing the magnificent house Blitz and his family built in Santa Rosa. Whether that second chapter in his life redeems him or not is up to Dear Reader to decide – or maybe you’ll read this and come away feeling he did nothing amiss and was treated unfairly. Either way you’re likely to have strong feelings about him, just as your Bay Area great-grandparents probably had.

When Blitz was born in 1858 his father was already on his way to a fortune; by the time he reached adulthood, theirs had to be the richest family in the north end of Sonoma county. John A. Paxton was a banker and investor who was among the founders of the Santa Rosa Bank and president of the town’s gas company, among other investments. He built the family a 17 room manse in 1880-1881 west of Healdsburg in the fashionable Second Empire style which is still around; you probably know it as the elegant Madrona Manor B&B.

In those years John spent the workweek at his San Francisco bank office, returning on the Friday train where he was met by a servant. “If the weather was a bit nasty, the coach and footman arrived in a closed carriage – some class!” Wrote Dr. William C. Shipley, the Boswell of old Healdsburg. Shipley described the Paxtons living like gentry. “There was a footman, groom and several maids. They had quite an entourage in keeping with their position and wealth, yet with it all they were perfectly likable human people…the whole town gloried in their dignity, majesty and power, but none were envious.” It was a grand life.

According to the biographical sketch of Blitz in the 1911 county history (always self-serving because the sketchee paid to be included) young Blitz had a series of office jobs for a silver mine, a bank owned by his father and a dried fuit distributor. But unspecified “failure of his eyesight” caused him to stop working,

Blitz married Elizabeth “Bessie” Emerson in Healdsburg in 1882. She was from Rochester, New York and they likely met because her sister, Luta, had married into a prominent Healdsburg family and was living there. Bessie was the seventh of eleven children (no twins, either) all of whom lived to adulthood. Her father was an entrepreneur who ran many businesses; her mother was likely exhausted from running after so many children before dying at age 42.

The marriage of Bessie and Blitz quickly soured. A son, John, was born after their first anniversary but while the boy was still an infant, he and his mother were living back in Rochester with her father. It’s unknown whether Bessie or Blitz knew she was again pregnant at the time they separated.

Soon after they split in mid-1884, Blitz left the country for 6+ years traveling in Latin America, then Europe. What he did in those years is a mystery; the hagiography in the county history notes only that “a number of years were pleasantly and profitably passed.” (The history does not mention Bessie and their kids, by the way.)

While he was abroad, his father John disinherited Blitz not once, but twice; the first codicil in 1885 dropped his quarter-share in the $750,000 estate, and the next change took away his one-eighth interest in the farm. Just a few months later, John died in 1888 aboard a ship en route to London, where he was expected to meet – and presumably, reconcile – with Blitz.

Three months after John died, his mother, Blitz was joined in London by his mother, Hannah, and her niece. The three of them toured Europe together, so presumably the only one in the family that had a beef with Blitz was his dad.

Blitz returned to California in late 1890, moving into the grand house at Madrona Knoll Ranch with his mother and aunt. The year before he died John built a two-story winery with an impressive 200,000 gallon capacity; Blitz assumed control of this and other family business. Little happened for the next few years – until Hurricane Bessie landed in 1894.

Overnight the Paxtons found themselves cast as villains in a titillating scandal covered by the yellow press on both coasts.

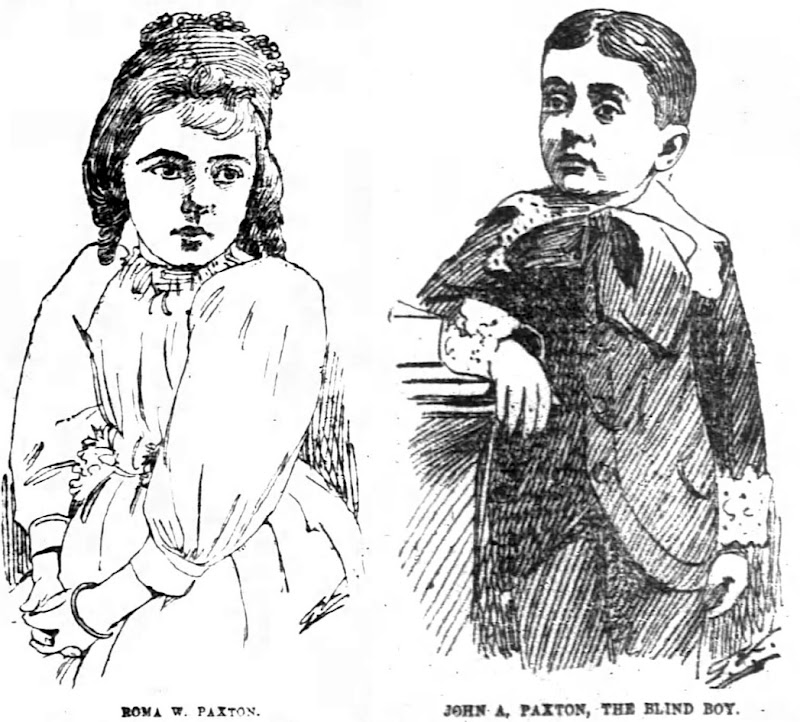

|

| Bessie and Blitz Paxton illustration from San Francisco Chronicle, May 11, 1894 |

Bessie sued for divorce, charging Blitz had deserted her ten years earlier and had refused to provide child support – and for good measure Bessie also sued his mom for $100,000, claiming she caused “alienation of her husband’s affections.” The divorce was granted but Bessie and Blitz would battle over support for the next eighteen years, making it surely the longest dustup in the history of Sonoma county courts.

Over the years, charges flew. In a later suit she claimed that she went to live with her father because “drugs he compelled her to take wrecked her health and caused her great suffering.” She said he had provided almost no child support, but when they corresponded a year after the separation, Blitz allegedly offered half his fortune ($25,000) – although according to Blitz, she instead unsuccessfully tried to shake down his father for twice as much. (Blitz later said his first disinheritance was because his father didn’t want her to benefit in any way from his estate.)

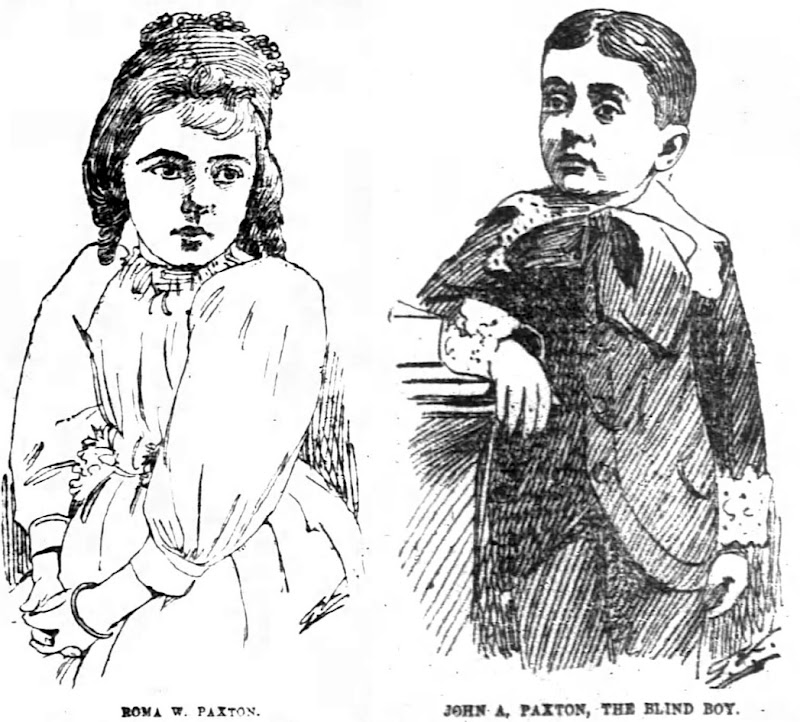

The core of Bessie’s demand for money was always her children being helpless dependents. Son John had been completely blinded a few years before the divorce in some sort of accident, and his sister, Roma – born after her parent’s separation – was portrayed as an invalid, although nothing specific was ever claimed except that she was “delicate” for once having hit her head. (Roma married in 1908, had four kids and lived to the great old age of 85.)

As the years passed and new lawsuits were filed, Bessie’s pleas became more strident and dramatic. She sobbed in court testimony, claimed that her children were about to go hungry as she was months overdue on all bills. She blasted her wealthy ex-husband as every kind of monster – although in a 1906 appearance she turned her ire towards Blitz’ attorney (and seemingly his best friend) James Wyatt Oates: “I know that if he were left alone Mr. Paxton would provide for me and my blind son, John, and my invalid daughter, Roma,” she complained in 1906, “but Attorney J. W. Oates of Sonoma, who represents Mr. Paxton, will not let him settle the case, because the longer it goes on the larger will be his fee. This is common talk at our old home and is a fact.”

Even as Bessie kept escalating her claims of pauperism, Blitz likewise kept deflating the size of his bankbook. He claimed at various times he was “practically bankrupt,” his investments had flopped, he was “in such bad shape that I cannot tell at this time what I will be able to do,” had no income because he could not work due to gout and heart disease (yet somehow managed a week-long fishing trip with Oates), had “no coin, and no property on which he can raise any” or was nearly penniless from paying lawyers to fight Bessie. In 1905 he filed an affidavit claiming he was flat broke – yet three months later, hosted a party for 300 at his grand Santa Rosa home.

From the beginning of their courtroom conflicts, the San Francisco press framed the story as the cold-hearted millionaire fighting the impoverished mother of his children and his pitiful children. During the 1894 divorce case the Chronicle was unusually honest in suggesting this spin was selling lots of papers: “The article published in the Chronicle lately concerning the suit…caused a sensation here and in Sonoma county, where the wealthy Paxton family is well known. The narrative of Mr. Paxton’s treatment of his young wife and their two children was interesting reading in the clubs and swell places which he frequents.”

Flash forward a few years later and the San Francisco Call offered a headline, “PAXTON HUNTS DUCKS AND CHILDREN STARVE.” Scattered among the selection of articles transcribed below are a few other examples of the anti-Blitz spin (and there are certainly more) but this snark from the 1906 Call is my favorite:

Every parent in the animal kingdom, by studied proximity and conscious sacrifice, feeds and shelters its offspring. Then why does Blitz W. Paxton stand alone? There are some animals that devour their young. Then there is the canis tribe – a class by themselves of carnivorous mammals, such as the dog, the fox, the wolf and the jackal, but these all outclass Blitz W. Paxton in the support and shelter they universally supply to their offspring.

Was Blitz really that rich and was Bessie really that poor? More on Blitz is below and in the following article, but he was never close to being the Daddy Warbucks who Bessie portrayed. And it’s very doubtful she or the children ever faced real financial hardship.

Bessie apparently returned to California in 1892, not long after Blitz came back from Europe. She and the children settled in San Francisco where her brother-in-law (General Richard H. Warfield, the husband of her sister Lute) leased and ran the California Hotel in the city’s fashionable French Quarter centered around the intersection of Bush and Kearny. She remained a “permanent guest” there at least through 1899 – as a side lawsuit in the divorce proceedings, Warfield demanded Blitz pay $315 for two years of food, clothing and boarding.

While the press was telling readers that poor Bessie was counting nickels, she was actually hobnobbing with elites on Nob Hill, particularly multimillionaire James Graham Fair (he’s the “Fair” in the name of San Francisco’s Fairmont Hotel). A notorious philanderer whose wife had divorced him for “”habitual adultery,” Fair died the year after the Paxton divorce. Women came forward claiming he had promised to leave them a generous bequest and rumors were that Bessie had a final will which named her a major beneficiary; it wasn’t true, but it suggests the newspapers presumed she and Fair had a very close relationship.

The Paxton divorce was settled in the autumn of 1894: Bessie would get $7,500 in cash and $100 a month until the children were of age. Blitz also took out a life insurance policy naming her and the kids as beneficiaries. It wasn’t a grand sum, but $100/mo in 1894 works out to about $40,000 a year in today’s money – and remember, she was apparently paying little for living expenses at her family’s nice hotel.

Following the divorce settlement and the flurry of excitement over the Fair affair, all was quiet concerning the former Mr. and Mrs. Paxton until the turn of the century. Then: Vaudeville!

(RIGHT: Bessie Blitz Paxton vaudeville publicity photo)

Bessie had long fancied herself a singer, and as far back as the original divorce suit she claimed of being “forced to sing in church choirs” to support herself and the children. It comes as news to me that was ever considered a well-paying gig, but she later expanded her claim to “singing in oratorio” and opera, although never were any specifics provided. (Full disclosure: I myself was in two productions of the New York Metropolitan Opera and can likewise say I have made operatic appearances. In one I marched onstage with other spear carriers and in another I waved a flagon in a tavern scene.)

In 1900 she made her first appearances in San Francisco and Los Angeles to polite reviews. Her voice was low but carried well and said to be “velvety in quality.” Her stage name was “Mrs. Bessie Blitz Paxton” to milk the divorce infamy and per usual, she worked in a dig at Blitz when interviewed: “[T]here are bills to be paid,” she told the San Francisco Call, “doctor’s bills the result of my little daughter’s recent illness. Her father won’t pay them so I must, and I am going on the stage to earn the money.” Ever sympathetic, the Call’s headline was, “SINGS IN PUBLIC FOR HER CHILDREN.”

The following year she did an East Coast tour which did not go so well. She began with a troupe playing Midwestern cities. (Lincoln, Nebraska review: a “California society woman with charming vocal powers and a most peculiar manner.”) Bessie was fired a few weeks later for punching the leader of the company after he chided her for a lack of professionalism. According to the Los Angeles Herald, “She wheeled him around and out into the [train] aisle and planted a No. 5 [boxing lingo for an uppercut punch] where it was the most forceful.” She ended 1901 on stage alongside bottom-of-the-barrel acts such as the Carmen Sisters (“banjoists”) and “Fritz the monkey, who turns wonderful somersaults.” For a few weeks she apparently tried to relaunch herself as a novelty act: “Alice Blitz Paxton, The Female Baritone.”

Back home the legal battle with Blitz resumed, this time over a $918 medical bill for daughter Roma. Blitz argued he should not have to pay for it as he did not authorize the treatment and the state Supreme Court agreed. It was another example where he easily could be viewed as heartless – but that was a hefty bill (about $29,000 today) and we have no information about Roma’s ailment or medical treatment. All we have to judge its merits is that the physician was Dr. Grant Selfridge, a homeopath who specialized in hay fever and allergies.

This brings us to 1902, probably the most eventful year of Blitz’ life. He was now president of the Santa Rosa Bank, of which his father was a founder; he had a new wife and a new son and the family had moved into their fine new house in Santa Rosa. That year his mother also died, which seemed to make him the rich man Bessie had always falsely presumed him to be. Soon she was back demanding he double the alimony payments. This round of their epic fight would continue from 1903 to 1908.

Rehashed once again were the accusations from their old separation, with some new details added: Bessie now accused him of stashing away their $500 wedding silverware. It was probably Bessie’s stage experience which brought tearful and wrathful drama to her court appearances, including a moment where she attacked Blitz in the courtroom like a bulldog prosecutor:

Springing to her feet, bitterness marking every gesture, Mrs. Paxton walked toward the man whose abandonment of her has cost her years of suffering, and said:

“And who, if it please you, took care of your children when you took $40,000 from the bank and went to Europe for a good time? You say, you should support these children. You had an opportunity before any suit was filed, but you turned your blind son away from your home when he went to ask for aid.”

Paxton winced and reddened, but tried to smile unconcernedly.

“Oh, you may well laugh,” said Mrs. Paxton, “when you are living in luxury and we are starving.”

At first Bessie’s new legal campaign against Blitz might seem like the action of someone foolish or desperate. He was no longer required to pay child support as John and Roma were no longer minors, being 22 and 20 (respectively) in 1905, the key year for their court decisions. But requesting more alimony was merely a clever gambit by her lawyers; under California’s Civil Code §206 there was an obligation for parents to support children who could not provide for themselves because of infirmities – regardless of age. Now his children were individually suing him as well.

Blitz was ordered to pay Roma and John $50 a month each. He refused and his children’s lawyer asked for him to be imprisoned on contempt. As reported in the Call, their attorney told the court that Blitz was such a monster that he even refused to see his kids after they trekked all the way to Santa Rosa on their own:

Last week, alleges Attorney Hanlon, John, the blind son, and Roma, the invalid daughter, went to Santa Rosa to ask their father for aid, as the court had decided that not only morally but legally he was bound to support them. Leading her sightless brother by the hand, says Hanlon, Roma trudged from the station along the country road to the splendid home of their father. Up the drive they had once hoped would lead them to their own doorway they walked, two children intent upon executing their own judgment, but they were to be disappointed…when these children turned into the driveway leading to their father’s home he was sitting at his ease at that home. But as the children approached the blinds were drawn and a servant was dispatched to meet John and Roma. ‘Your father is not at home,’ said the servant. ‘He has gone to San Francisco. I do not know when he will return.’ Thus repulsed, these children turned back to the station, penniless.”

I tell you, the reporting on the Paxton court hearings was the best entertainment available during the autumn of 1905. Forget sports, forget politics; you can bet everyone in Northern California was eagerly flipping through their morning papers to see if there was a fresh salvo from Bessie and the kids or whether Blitz had finally sprouted horns and a tail.

While Blitz was being threatened with the court seizing his share of Madrona Knoll and/or throwing him in the clink for contempt, Bessie’s society friends organized a gala concert on her behalf at the Tivoli Opera House. “When the total receipts were figured up if was found that a fund of fully $2000 was ready to relieve the temporary embarrassment of the brave Mrs. Paxton and her family,” the Call reported.

Years were passing and like a soap opera storyline, details changed while the plot remained fundamentally the same. Court decisions kept falling in favor of the children, with one point being appealed to the state Supreme Court. John bitterly demanded judges to punish his father. Blitz said he had no property to sell, which was true – he had transfered the Santa Rosa house to wife Jane on New Year’s Eve 1904. The only thing he truly owned was roughly one-third of the Healdsburg property which he had inherited from his mother. Bessie’s lawyers had estimated his share at over $100,000, but much of its value was in the productive winery. That building collapsed in the 1906 earthquake and was not rebuilt, so when Madrona Knoll was sold at the end of the same year Blitz cleared only about seventeen thousand.

And lo, it finally came to pass, eighteen years and four U.S. presidents later: In 1912 there was a settlement for all claims. Blitz paid $5,000 to each of his kids.

Blitz always claimed (at least, when he could find a reporter willing to listen to his side) that he didn’t object to supporting his children, but rather objected to any money reaching the ex-wife he and his family loathed. From a 1905 affidavit:

The affiant admits that he deserted and abandoned his former wife, Mrs. Bessie E. Paxton, but asserts that he was compelled to do so, owing to her meanness of temper and bitterness of tongue; which made the life of this affiant unbearable. Mrs. Paxton further alienated the affection of the parents of this affiant for him and when this affiant returned from his trip abroad, it was only to learn that his father, John A. Paxton, had absolutely disinherited him, as he did not wish Mrs. Paxton to benefit in any way from his estate, owing to the meanness of her conduct.

This contempt for Bessie was also seen in his mother’s will, where Hannah Paxton only left a token $10 each to her grandchildren Roma and John Jr. And it is true that any contribution to John would have been a benefit to Bessie; he apparently lived with his mother until she died in 1937. (He passed away two years later.)

And even before the settlement, Blitz did aid his son. In 1907 he paid for the 24 year-old John to run a cigar stand on Sutter street, but his blindness left him open to theft. Blitz started another at California and Divisadero streets but again was robbed of everything. While today it might seem a setup for failure – or even cruel – to encourage a sightless person to operate a street business like that, magazine and tobacco stands were a common business for the blind in that era, and John did it for the rest of his life.

Personally, I feel Blitz and Bessie were equally despicable for turning John and Roma into pawns. It might look like a zero-sum game but wasn’t; both parents considered they won a moral victory every time he ignored a court order to pay up. Money was only a phony excuse to go to war over their mutual hatred. I very much doubt either of the children ever suffered cold or hunger, but am certain both must have been scarred emotionally by being pushed to the battlefield frontlines in the roles of the pathetic invalid girl and blind boy.

Finally, if l’affaires Blitz haven’t left you totally exhausted, you can open the Paxton matryoshka doll and find another collection of sensationalistic lawsuits, and still more court battles nested inside that one.

Blitz had a younger brother Charles, who was not mentioned here before because he has no real Sonoma county connection. He was a San Francisco stock broker and after their mother died in 1902 the brothers were named co-executors of the estate. Within the year Charles was accusing Blitz of embezzlement while Blitz was trying to force Charles out, charging he threatened “to destroy his reputation and to drive him out of Sonoma county.” Meanwhile, the Santa Rosa Bank – where Blitz was still president – sued the pair of them as executors for not paying back the loans mom took out for Blitz’ allowance in the 1890s. Then when Charles died and Blitz was executor of his estate there were still more lawsuits. At one point I think I read Blitz was suing himself, but am probably wrong about that. Still, as crazy as that seems, you couldn’t blame the poor fellow for getting mixed up over such a little detail.

|

| Roma and John A. Paxton illustration from San Francisco Chronicle, May 11, 1894 |

MRS. B. W. PAXTON SUES FOR DIVORCE

She Says Her Millionaire Husband Treated Her Cruelly and Deserted Her.

SAN FRANCISCO, March 10.–A complaint was filed to-day in a suit for divorce by Mrs. Bessie E. Paxton against Blitz W. Paxton, who is reported to be worth two millions of dollars. Paxton comes from a rich family in Santa Rosa, Sonoma county, and his fortune is largely in land and mining property.

The plaintiff, who is a young and handsome woman, says they were married in 1882 and lived happily until 1884. She had one son and was expecting another child when Paxton deserted her. She gave birth to a daughter, Roma, on Jan. 3, 1885, and her health was seriously affected by her husband’s cruelty.

His action she ascribes to his parents, who desired him to separate from her. He induced her to return to her father and mother in Rochester, N.Y., promising to meet her there after paying a business visit to Texas. She fulfilled her part of the compact, but her husband returned here, and then went to Guatemala. She learned nothing of his whereabouts until the following year, when he wrote that he should never come back to her.

For eight years, the plaintiff declares, she has supported herself and her two children aided by her parents, receiving no more than $125 last year from Paxton. He refused any further aid, although his little son is totally blind and requires the mother’s constant care. Mrs. Paxton alleges that her husband is living in luxury and that he spends large amounts at costly restaurants on periodical visits to San Francisco, while she is forced to sing in church choirs and give music lessons to get the simplest necessaries for herself and children.

The plaintiff has also secured an injunction restraining her husband from disposing of any of his property, and she demands money for support and counsel fees during this action. The complaint, when it is published tomorrow, will create a social sensation, as Paxton is a well-known club man and a member of San Francisco’s four hundred.

– New York Sun, March 11 1894

Paxton Repudiates Doctor’s Bill.

The action instituted by Dr. Grant Selfridge against Blitz W. Paxton and his former

wife, Bessie E. Paxton, who recently abandoned the society drawing-room for the vaudeville stage, to recover $918 for treating the son of the defendants, was tried and submitted for decision by Judge Seawell yesterday. Dr. Selfridge and Dr. J. S. Brooks testified as to the reasonableness of the plaintiff’s claim. Mr. Paxton was placed on the stand in his own defense and repudiated the claim saying that he did not authorize the treatment of his son by Dr. Selfrldge. The case was then argued and submitted.

– San Francisco Call, March 20, 1901

MISHAP TO HARRY CORSON CLARKE

Bessie Blitz Paxton Chastises tha Actor

DENVER, Col., April 25.–Harry Corson Clarke undertook to reprimand Bessie Blitz Paxton, the plump land who sang “Twickenham Ferry” with the Clarke company, with results disastrous to himself.

While the company was en route to Cheyenne, Mr. Clarke undertook to tell Mrs. Paxton how little she knew about the show business, and how much she could learn from hum. He also referred to her failure to attend rehearsals, and ended by an expression which aroused the actress to more real anger, she says, than she has felt since he was married.

Bessie Blitz Paxton thereupon arose in her wrath and her car seat and swatted Mr. Clarke on the ear. She reached over with the other hand and jolted the comedian under the chin. Then she took a firm hold at the nape of his neck, and another and firmer hold farther down, and threw him up against the window sash. She seemed to be trying to let go of him, but could not. She wheeled him around and out into the aisle and planted a No. 5 where it was the most forceful, and Mr. Clarke dived into the stove box.

The rest of the company interfered and held Mrs. Paxton until Cheyenne was reached. Here Mr. Clarke paid her two weeks’ salary, and the actress returned to Denver, arriving this morning.

– Los Angeles Herald, April 26, 1901

FILED FOR PROBATE

THE LATE MRS. H. H. PAXTON LEFT PROPERTY VALUED AT OVER $200,000

Will and Codicil Dispose of the Estate the Bulk of Which is Bequeathed to the Deceased Lady’s Two Sons

Blitz W. Paxton has petitioned the Superior Court for probate of the will of the late Mrs. Hannah H. Paxton of Madrone Knoll, Healdsburg,

Among other things the deceased’s property consists of an undivided five-eighths interest in 208 acres of land known as the “Madrone Knoll” place, the interest being valued at $62,500; furniture, furnishings, etc., valued at $5,000; jewelry, etc., $1,000; 200 shares of stock of Santa Rosa Bank valued at $28,125; cash in bank, $889; 60 first mortgage bonds valued at about $60,000; shares of Puget Sound Iron Co., worth about $28,000; an undivided interest in personal property worth about $2,500; Interest in wine 1 bond worth $2,600. T

The value of the property is about $200,000. Mrs. Paxton left a will bearing date October 11, 1894. with a codicil thereto dated January 24,1899, in the possession of Colonel James W. Oates, who is the attorney for the estate. Blitz W. Paxton. Charles E. Paxton and Mary M. McClellan are named in the will as executors.

In the will the deceased’s bequests Include $5.000 to her sister, Miss Mary McClellan; her sister, Ruth McClellan, $6.000; John A, Paxton and Roma W. Paxton, her grandchildren. $10 each.

To her son, Blitz W. Paxton, Mrs. Paxton leaves a legacy of $40,000.

All the residue and remainder of the estate is left to Blitz W. Paxton and his brother, Charles E. Paxton, in equal proportion, share and share alike. The reason for the additional legacy to the former son is explained by the testator for the reason that he did not share his father’s property at the time his brother did, the latter being left about $40,000.

In the codicil to the will, made January 24, 1899, Mrs. Paxton absolutely Revokes the bequest of $5,000 to her sister, Miss Ruth McClellan. The executors will serve as such without bonds and they are given power to buy. sell, convey, compromise, manage and control the estate.

– Press Democrat, September 9 1902

She Wants More Money

Mrs. Bessie Paxton has petitioned the Superior Court of San Francisco for an order to compel her former husband, Blitz W. Paxton, to allow her $200 a month. At present she receives an allowance of $100, but she declares that this is insufficient for the support of herself and her two minor children.

Mrs. Paxton obtained a divorce in 1894, and at that time was awarded the custody of her two children, John A. Paxton,now aged 20, and Roma Warren Paxton, now 18. When the divorce was granted Mr. Paxton offered his wife half of $25,000, his fortune at that time. She refused this and went to his father for $50,000. He would not listen to her, and finally when the divorce was granted, she accepted $7,500 in cash and $100 a month to be paid until the children were of age.

Mr. Paxton believes that the children will soon be legally out of her custody, and according to the stipulation she will no longer get the $100 a month. “That is not in any sense alimony,” said Mr. Paxton. “The $7,500 was in lieu of that. I carry a $10,000 insurance policy made out for her benefit and that of the children. 1 will make different arrangements for them when they are out of the legal custody of their mother.” Mrs. Paxton’s petition will be heard on August 21.

– Press Democrat, July 9 1903

LAW IS WITH BLITZ PAXTON.

Banker Defeats His Former Wife in Her Efforts to Get Increase in Alimony.

A petition to modify a decree of divorce, the means taken by Bessie E. Paxton, the singer, the former wife of Blitz w. Paxton, the Sonoma County banker and capitalist, to secure more alimony, is not the proper proceeding, hence Judge Murasky found against her yesterday, and ordered the entry of an order denying her petition. She must file a suit in equity to set aside the agreement she made at the time she secured her divorce, in which she waived all claims against Paxton for the sum of $13,200 to be paid in monthly installments of $100, which agreement, she claims, was obtained from her by misrepresentation.

The matrimonial history of the Paxtons is a stormy one. They were married in 1882, and have two children, a boy and a girl. The boy, who is now almost 19 years of age, is blind. The troubles of the Paxtons commenced a short time after their marriage. In 1894 she sued him for divorce and obtained a decree on the ground of cruelty. She agreed that she would waive all claims upon Paxton provided that for a period of 132 months he would. pay her $100 a month. When the children grew up and the boy lost his sight and the girl became sickly, Mrs. Paxton found it hard to make both ends meet on $100 a month, and she went upon the stage. For a period of two weeks she sang at the Orpheum. Then Paxton fell heir to a fortune estimated to be worth $500,000, and Mrs. Paxton thought it about time that he should do a little more for her than give her $100 a month. She accordingly filed the suit to amend her decree of divorce, basing her claim on the ground that Paxton, to obtain her signature to the agreement concerning alimony, had willfully and fraudulently concealed the true state of his finances.

– San Francisco Call, March 26, 1904

DEMANDS AID FROM FATHER

Daughter of Blitz Paxton, Banker, Files Suit to Compel Him to Support Her

GIRL PLEADS POVERTY

Says She Is an Invalid and in Need of Necessaries. Marriage Bonds Severed

The litigation growing out of the matrimonial infelicities of Blitz W. Paxton, the Santa Rosa banker, and Bessie Paxton the singer, which began in 1893, when Mrs. Paxton sued for maintenance, and which was further complicated in 1894, when she dismissed the maintenance proceedings and instituted a suit for divorce, became still more involved yesterday, when Roma Paxton, the 19-year-old daughter of the couple, filed a suit against her father to compel him to support her. She says she is an invalid, unable to work to provide either the necessaries of life or medical attention for herself, and she asks the court to order her father to provide for her out of the fortune of more than $100,000 she says he possesses. She asks for $100 a month.

– San Francisco Call, May 27, 1904

Sues for Maintenance.

John A. Paxton, the blind son of Blitz W. Paxton, the wine grower and backer,

brought suit yesterday to compel his father to provide for his support. The young man’s parents were divorced in 1894 and since that time the son has been living with his mother. He came of age on August 10 and It is now alleged that owing to his infirmity and need of constant medical attendance his mother is unable to provide for him.

– San Francisco Call, September 11, 1904

The Paxton Case.

Divorced wife tells her story in San Francisco Court.

Divorced in 1894.

“Since my husband, without cause or explanation to me, his bride of two years, abandoned me at the behest of his family twenty-one years ago (1884), I have struggled alone, while he has disported himself in luxury,” said Mrs. Blitz Paxton (Bessie Emerson Paxton), wife of the Sonoma Banker, when the suit of her two children against their father for maintenance came up before Judge Graham Friday in San Francisco.

“I simply worshipped my husband; when the blow fell on me I was nursing my little baby boy (John Alexander); my little girl (Roma) was born afterwards. Then misfortune seemed to pursue us; accidents happened to both children, a hard fall in each case rendered them helpless for life, my son having been blind from babyhood. An operation, the doctors said, would save his eyes, but my appeal to his father was in vain. Then it became too late to do anything for his sight. My daughter is delicate from a fall which caused concussion of the brain.

“I tried for awhile to turn my musical training to account, and the songs of happier days, when I entertained guests at my luxurious home, were heard on the Orpheum Circuit. But the children needed my care, and the work was too hard. This suit seems our last hope for relief.

The case was argued and taken under advisement by the court.

– Healdsburg Tribune, June 1, 1905

PAXTON WINCES UNDER CHARGES.

Former Wife Verbally Flays Santa Rosa Banker for His Acts Toward Children.

COURT SCENE DRAMATIC.

Mother of Plaintiff Rises and Replies to Defendant’s Statements on the Stand

Blitz W. Paxton, Santa Rosa banker and capitalist, winced under the verbal lash, wielded by Bessie W. Paxton, who was once his wife, in Judge Graham’s department of the Superior Court yesterday. He was in court to fight against the petitions of his blind son and invalid daughter for maintenance. Well-groomed and showing in his dress every evidence of the possession of the wealth the mother of his children says he enjoys to their exclusion, he glanced at the sightless eyes of his son and at the frail form of his daughter without the faintest display of emotion.

With the eyes of the spectators upon him and the accusation of his former wife ringing in his ears he was less at ease, however.

Paxton first presented an answer to his children’s petition in which he denies that he is possessed of the hundreds of thousands of dollars with which they credit him and says that he is worth no more than $30,000. He also presented an affidavit signed by his physicians in which it is stated that rheumatic gout and heart disease compelled him to relinquish his position with the Santa Rosa Bank, which left him without salary or income other than that derived from his small estate, which, he says, he needs for the support of his present wife arid child.

PAXTON MAKES ADMISSION.

Upon taking the stand the capitalist admitted, in answer to questions put by Judge Graham, that he believed he should support his children, but, he said, “I will contribute nothing to them that might be used by their mother for her support.”

Springing to her feet, bitterness marking every gesture, Mrs. Paxton walked toward the man whose abandonment of her has cost her years of suffering, and said:

“And who, if it please you, took care of your children when you took $40,000 from the bank and went to Europe for a good time? You say, you should support these children. You had an opportunity before any suit was filed, but you turned your blind son away from your home when he went to ask for aid.”

Paxton winced and reddened, but tried to smile unconcernedly.

“Oh, you may well laugh,” said Mrs. Paxton, “when you are living in luxury and we are starving.”

Paxton was silent under the stinging accusation.

In an affidavit Mrs. Paxton said that since the expiration in August of an agreement entered into between herself and Paxton at the time she divorced him in 1894, under which he paid $100 a month for the support of his children, Paxton has only sent them $40, and that was to his blind son John. To his daughter Roma he sent nothing.

NO FOOD IN HOME.

“Why, even now,” said Attorney. Hanlon, interpolating, “there is no food in the home of these people that are in sore need.”

Again Paxton smiled; he found grim humor in the lawyer’s statement.

Continuing in her affidavit Mrs. Paxton recited the facts of the abandonment of herself

and her children by her husband, who had become angered, she said under oath, at her through her refusal to submit to criminal means to stay the advent of her baby girl into the world. She said he sent medicines and got a doctor. In his effort to compel her to submit to his demand, but she refused, and although her daughter had been sorely tried through illness her gentleness of spirit has brought much comfort into a stricken home.

At the conclusion of the reading of Mrs. Paxton’s affidavit, in concluding which she reiterates her statement that her former husband is a wealthy man and that his statement to the contrary is made solely to defeat the effort of her children to secure a judgment for maintenance, the case was continued until next Friday to enable Paxton to file counter statements, signed under oath.

– San Francisco Call, October 14, 1905

Pretty Hard Up.

An affidavit by Blitz W. Paxton, of Santa Rosa, as to his lack of money was filed in Judge Graham’s court Friday in response to the application of John A. Paxton and Miss Roma Paxton, his two children by his first wife, for an order to compel him to pay their counsel fees and costs in their suits against him for maintenance. Paxton declares on oath that he has no coin, and no property on which he can raise any. His stock in the Sonoma Consolidated Quicksilver company has no market value, he says, and his stock in the Santa Rosa bank and the Puget Sound Iron company is pledged to the Wickersham Banking company for more than it is worth.

– Healdsburg Tribune, February 15 1906

BESSIE PAXTON PLEADS FOR AID

Asks Judge Graham to Intercede for Her With Former Husband, Who Is Rich.

SAYS RENT IS UNPAID.

Explains That Her Credit With Tradesmen Is Exhausted and Hunger Nears

“For God’s sake, Judge Graham,” said Mrs. Bessie Paxton on the stand yesterday, “Intercede for me and my children with Mr. Paxton! You have stilled resentment in many hearts and have brought contentment to many unhappy mothers, and why cannot you do this for me?” Here the unfortunate woman, once the wife of Blitz W. Paxton, capitalist of Sonoma, broke down and sobbed bitterly. For several minutes there was silence in the court until Mrs. Paxton partly composed herself. Then she continued:

“I do not know what we will do, Judge. My rent has not been paid for three months; my credit at the butcher’s, the baker’s and the grocer’s, is exhausted and my gas bill is overdue two months. We have nothing but a gas stove in the house, and if the gas is shut off we will have no way to cook our daily meal. We have now but one meal a day, and as the weeks pass we find that we must further economize, even in the amount of food that we can have at this one meal. It is dreadful, and I fear that my mind is breaking under the terrible strain.”

“I know that if he were left alone Mr. Paxton would provide for me and my blind son, John, and my invalid daughter, Roma, but Attorney J. W. Oates of Sonoma, who represents Mr. Paxton, will not let him settle the case, because the longer it goes on the larger will be his fee. This is common talk at our old home and is a fact. Cannot you intercede for me?”

“Well,” said Judge Graham, visibly affected by the, unhappy woman’s appeal, “l have done and am doing all I can for you. The last time Mr. Paxton appeared in court I asked him why he did not conduct himself like a man and see that you and your children were kept from want, but my criticism had no effect upon him.”

Still in tears, Mrs. Paxton left the stand to listen to the argument of counsel on the motion of her children for an allowance pending the hearing of their father’s appeal from Judge Graham’s order directing him to pay them $50 a month each for their permanent maintenance. At the conclusion of the argument Judge Graham allowed the two children $350, but when they can collect that, sum is a matter for conjecture.

The case thus decided, Attorney John M. Burnett, who represents Paxton in this city, requested Attorney Charles F. Hanlon, who represents the children, to consent to the printing of the transcript on appeal in but one of the two cases involved. “This will save us great expense,” said Burnett.

“If you will agree to give these children 75 per cent of the cost of the second I will release you,” answered Hanlon.

Burnett would not consent to such a proposition, Attorney Hanlon settled the dialogue by saying:

“Mr. Burnett, you have chosen to live by the sword, and you can die by it. Prepare both transcripts and turn into useless print the gold that would buy these children food. You have given none, and hence you can expect no quarter, from us.”

– San Francisco Call, February 22, 1906

PAXTON BENEFIT A BIG SUCCESS

Success, artistic at every point, and in a financial way far beyond expectation, marked the testimonial concert given to Mrs. Bessie Paxton, former wife of Blitz W. Paxton, and her two children, at the Tivoli In 19 House, in San Francisco, last Tuesday afternoon. Members of society flocked to hear the delightful program that had been prepared for them by Mrs. Camille d’Arviile Crellln, to whom most of the credit for the tremendous success of the affair must be given. When the total receipts were figured up it was found that a fund of fully $2,000 had been realized to relieve the temporary embarrassment of Mrs, Paxton and her children.

– Healdsburg Enterprise, March 17 1906

“MADRONA KNOLL” GOES TO HIGHEST BIDDER

About one mile west of this city is located beautiful “Madrona Knoll.” It is one of the most picturesque and artistic homes of this county. Many years ago John A. Paxton, a wealthy mining man purchased the site, cleared it of an undergrowth of brush and built on the knoll a mansion for his home and that of his family. It is an ideal spot from which one may overlook the Dry Creek and Russian River valleys.

After the death of Mr. Paxton and his wife, several years ago, the home was occupied by Blitz W. Paxton, a son. Later he removed to Santa Rosa and engaged in the banking business. The famous madrone home then stood in the name of the heirs as an estate. In the last few year it was decided to dispose of five eights of the estate. Accordingly it was advertised for sale at auction to the highest bidder, Including the entire tract of land, the home and all personal property.

On Tuesday last the sale took place as advertised under the auctioneer’s hammer. Five eights of the estate and all the belongings went to the highest bidder, the Santa Rosa Bank. The five eights of the reality was sold for $25,000.

The five eights of the personal property was knocked down to the bank for $6000. The furniture in the home which belonged to Mrs. Paxton went to the same purchaser for $3800.

The other three eights of the property is owned by Chas E. Paxton of San Francisco.

The auctioneer was John Hansen of Sebastopol. Attorney J. Rollo Loppo of Santa Rosa represented the bank. Colonel Oates looked after the Blitz Paxton interests and Attorney W. H. Rex of San Francisco appeared for Chas E. Paxton. There was a fairly good attendance at the sale.

– Healdsburg Enterprise, December 22 1906

THE PAXTON CASE

Offer Made By Father to Contribute to Support of Blind Son

The long standing dispute as to whether Blitz W. Paxton should be compelled to support his two minor children John A. and Roma W. Paxton came to an end Thursday in Judge Graham’s court, San Frandisco, when the judge accepted Paxton’s offer that his interest in his mother’s estate should be turned over to the Judge as an individual to be used for the benefit of his blind son. The estate of Hannah Paxton was left to her two sons and is said to have been worth $100,000. John A. Paxton, who has been running a cigar stand on lower Sacramento street, is anxious to open a new stand up town, and his attorney. Charles F. Hanlon, said that $200 cash was necessary for immediate use. Judge Graham will use his good offices with Judge Seawell, in whose court the estate of Hannah Paxton now is. to obtain the cash, says a San Francisco paper. The order to show cause against Blitz Paxton was dismissed without prejudice pending the court’s investigation of his offer.

– Healdsburg Tribune, July 2 1908

PAXTON PAYS CHILDREN

By the payment of $5OOO to his two children by his first marriage in settlement of all claims, Blitz W. Paxton of Santa Rosa Friday brought to a close the litigation the children have waged against him for the last six years. The chief beneficiary is John Paxton, the blind son. He has been assisted by his sister, Roma, in the legal battle. Mr. Paxton, it is stated, has never been averse to paying for the support of his children, but made the long contest in an effort to prevent any of his money going to the support of his former wife.

– Healdsburg Tribune, September 26 1912

Read More