Dear Valley of the Mooners: The state will soon build a lockup there for morons who are outcast women, which is to say they are really prostitutes. P.S. Most of them will probably have chronic cases of venereal disease. P.P.S. It will be your patriotic duty to cooperate fully to show your support for our troops.

This odd proposition came up during the winter of 1917-1918, as California fully ramped up home front efforts for fighting World War I. Under the so-called “American Plan,” it was decided our draftee soldiers in training camps needed to be protected against booze and sex workers, so the Navy established “dry zones” around Mare Island and other military bases. Liquor could not be sold within this five-mile radius and brothels were likewise closed under military order. President Wilson expanded this further by declaring areas around shipyards, munition factories, and schools with military prep programs to likewise be temptation-free.

As explained in part one, this led to tens of thousands of women accused of prostitution nationwide being swept up in vice raids and held under “quarantine” without due process. For such women of Northern California, the state was proposing to build a secured building at the Sonoma State Home at Eldridge big enough to imprison 300.

Why they pitched the “moron” angle is less clear. In the early 20th century “moron,” “imbecile” and “idiot” were accepted quasi-medical terms (although the methods used to classify people as such were complete and utter bullshit). As the institution near Glen Ellen was still widely known by its old name as the California Home for Feeble-Minded Children, maybe it was thought there would be fewer objections from locals if the women supposedly were of lower than average intelligence.1

There was plenty of local pushback against establishing such a “moron colony” at Eldridge even after the projected number of inmates was reduced by two-thirds. Nonetheless, by the summer of 1918, there were 110 “weak-minded girls and young women” from San Francisco quartered there.2

When the federal government abolished liquor in the Dry Zones, it helped pave the way for passage of Prohibition after the war ended. Similarly, the interest in keeping prostitutes locked up continued unabated – although the excuse was no longer protecting the troops from disease in order to keep men “fit to fight.” As also explained in part one, the new call was to abolish prostitution in California by reforming the women – even if it was against their will (and likely unconstitutional).

The loudest voices calling for enforced reform were the women’s clubs. In April, 1919, they succeeded in having the legislature pass an act establishing the “California Industrial Farm for Women” which was “to establish an institution for the confinement, care, and reformation of delinquent women.” Any court in the state could now commit a women there for six months to five years. But where would this “Industrial Farm” be located? The state only considered two locations – both in the Sonoma Valley.

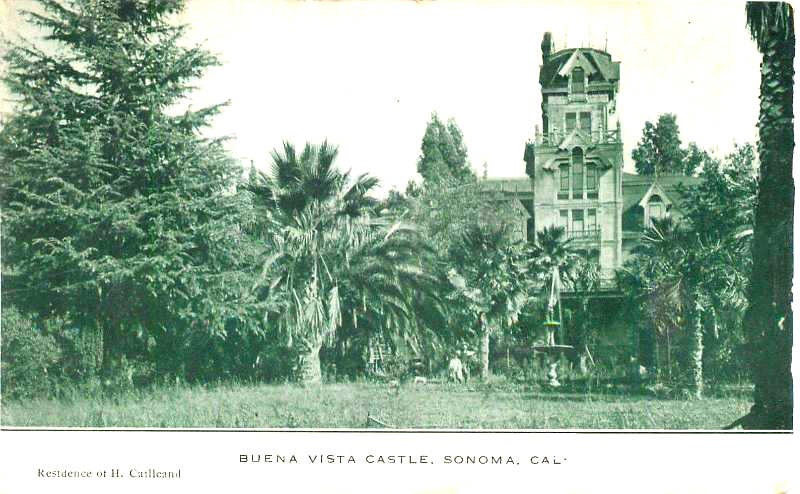

One possibility was the big chicken ranch of J. K. Bigelow between Glen Ellen and Sonoma (today it’s the Sonoma Golf Club, and the sprawling clubhouse is the “cottage” the Bigelows built in 1910). The other option was the old Buena Vista winery, where Kate Johnson, a philanthropist and noted art collector, had built a 40-room mansion in the 1880s. The state chose Buena Vista and began bringing in women after winning a 1922 test court challenge over a single inmate.

|

| A slightly different version of the colorized postcard shown in “THE MAKING OF A CRAZY CAT LADY.” From the Bartholomew Park Winery |

Battle lines formed. Women-based organizations – the clubs, League of Women Voters, the W. C. T. U. and other temperance groups – enthusiastically supported the “Industrial Farm” (it was also called the “Delinquent Women Home” and every variation in between; here I’ll simply refer to it as the “Home”). On the other side were politicians and bureaucrats (all male, of course) who thought the property could be put to better use, or just objected to the idea of spending taxpayer dollars trying to rehabilitate women of ill repute.

The attack on the Home locally was led by the Sonoma Index-Tribune, grasping at every opportunity to bash the place as a misguided experiment by do-gooders who foolishly believed they could domesticate feral humans. A scrapbook of clippings from the I-T during the 1920s can be found in the museum for the Bartholomew Park Winery (which traces its history back to Haraszthy’s original Buena Vista vineyards) and I am indebted to the winery – as well as the anonymous soul who originally assembled the scrapbook – for sharing that invaluable resource with me.3

The Index-Tribune’s bias was so unfettered we can never be certain how much of what they reported as fact was true – and alas, it was the only newspaper regularly covering doings at the Home. Sometimes the fake news is obvious; the I-T once claimed the monthly cost was $509.59 per inmate, but from later testimony and articles elsewhere we learn it was really in the $80-90 range, and was only that high because of building construction and other start-up costs.

A popular theme in the Sonoma paper was that the women were dangerous, depraved criminals. When the W. C. T. U. proposed incorporating some of the inmates from the women’s ward at San Quentin (almost all women at the prison were in for non-violent crimes, mainly check kiting and forgery), the Index-Tribune played up the “unthinkable” threat they would bring to the community:

| …We have had ample opportunity to judge the farm already, and do not hesitate to say that as a penal institution it is a failure, because it is a menace to the community and a nuisance to local officers…to bring 50 San Quentin inmates here, unconfined, without guards and a prison wall, is unthinkable. Surely the people of the surrounding country are to be thought of, despite theorists of the W.C.T.U. Perhaps if these good women knew how the handful already at the farm have acted, they would hesitate to pass their sob-sister resolutions. Perhaps if they were informed that there has been leaks, escapades and communication with companions on the outside, they might understand something of the danger such an institution is in our midst… |

That editorial appeared in September 1922, when the Home had been accepting women only about four months and had thirty inmates. The I-T rushed to declare it already a failure, although the only reported trouble had occurred the week before. The paper would still scream about that incident years later, and as with all other damning news from the Index-Tribune, their version should be presumed slanted.

Two women escaped, were caught and returned. They became belligerent and started a riot. The ringleader was arrested, handcuffed (a later rehash would say she was “hog tied”) and taken to the county jail in Santa Rosa. While enroute, “the prisoner, who is a drug fiend, hurled the vilest epithets at the officer.” Deputy Joe Ryan was immediately called back to the Home to arrest another riotous inmate, and the two women were sentenced to 40 days in the Sonoma county jail.

Six months later the Sonoma paper reprinted a Sacramento Bee report about another escape under the headline, “THREE WOMEN’S PRISON MILK MAIDS FLEE”:

| …[the] aesthetic atmosphere, created to comfort the women jailed because of commission of the sin that has come down the ages, now includes “lowing herds winding slowly o’er the lea.” At least, a herd of milk cows recently was installed at the home, there to replace a herd of milk goats. Perhaps the break for liberty taken from them was actuated by resentment over the transfer of the lowly but picturesque milk goat for the more impressive bossy. Or mayhaps the duty of parking a cow on the farm and relieving her of her fluid treasure proved more arduous to the three “sisters of sin” than being maid to the goats. This is not officially explained. It is officially admitted, however, that the maids three have gone…Anyway, the first big break has been staged at the prison farm. As far as is known, this is the first break from jail in California by three women. |

The Index-Tribune felt compelled to append an editor’s note: “The Bee was misinformed as to this being the first break. There is such a gap between the honor system and discipline at the prison farm that there is a jail break every week.”

As the I-T had not been reporting all those weekly “jail breaks,” the editor was either admitting such events weren’t newsworthy or didn’t happen. Either way, it opens the question: What was really going on at the Home?

Rarely mentioned was that a small hospital was built next door when the Home opened. The original 1919 Act specified that women only could be released “with reasonable safety and benefit to herself and the public at large,” which meant treating – and hopefully, curing – any venereal diseases. As discussed in part one, the best medical protocols in that era involved weeks of painful shots using solutions which had to be prepared under very precise conditions. Thus it’s safe to assume that the hospital’s (20? 30?) beds were filled at any given time.

The Act also called for the inmates to be given “industrial and other training and reformatory help,” but aside from milking those cows – and before that, goats – there was no mention of other work, aside from a later comment in the I-T about them “painting flower boxes and pots,” which could be just gratuitous snark from the editor. Nor was any formal education or training ever mentioned.

Before the place had a single inmate, Superintendent Blanche Morse was interviewed by the Press Democrat. “We are going to give the inmates work to do,” she said, “but we are not going to apply the institutional idea and make them do it to bells and march-time. Each woman will help around the house in some way.” To her and other women’s advocates at the time, the inmates would be transformed once they were lifted out of their abnormal environment. That meant placing these women – who came from San Francisco and other big cities – in the countryside to learn farm chores along with traditional domestic skills like sewing, laundry and housecleaning in a communal women-only setting.

(RIGHT:) Blanche Morse portrait used in the San Francisco Call 1911-1912

(RIGHT:) Blanche Morse portrait used in the San Francisco Call 1911-1912

Blanche Morse was the guiding force of the Home from the beginning. When the Home opened she was 52 years old, a former Berkeley librarian, middle school principal, and feminist with a decade of positions in several East Bay and state women’s groups. In 1911 she was a speaker and organizer on the historic suffrage campaign tour to gain the right to vote in California. Her complete lack of any background in penology or social work or administration might seem to make her unqualified to handle the unique problems of the women sentenced to the Home, but she still probably looked like the ideal person to many in 1920 – because of her activism with the Mobilized Women.

The “Mobilized Women’s Army” was a coalition of Bay Area women’s groups that organized in Berkeley just after the U.S. entered WWI in 1917. Its objective was to locally enforce “Americanization,” which was another creepy project of the Wilson Administration akin to the American Plan – but instead of unconstitutionally locking up women accused of moral crimes, Americanization sought to encourage citizens to spy on their foreign-born neighbors and intimidate them into behaving more like “real Americans.”

It was Blanche Morse who organized efforts to compile a list of every single immigrant in the Bay Area via a house-to-house survey – a list which would have been invaluable to the government and industrialists after the war during the “Red Scare” years, when both sought to crush Bolshevism and labor activism dominated by first-generation immigrants.

And just as the American Plan gained more steam once the war was over, the Mobilized Women’s mission became a well-funded program to push cultural assimilation. It was the Mobilized Women’s “American House” in Berkeley that clearly became the model for the learn-by-osmosis rehabilitation efforts at the Delinquent Woman Home at Buena Vista. There foreign-born women were shown American-style houswifery, which, as one scholar put it, meant “in order to be better citizens, immigrant women should learn to dress, shop, cook and clean in new, better, and more ‘American’ ways.”4

It’s unknown whether Morse’s delinquent women similarly adopted “American ways” and became prostitutes no more. That is, if they were prostitutes to begin with; according to the Sacramento Bee, of the 54 inmates there at the end of 1922, only 17 were prostitutes and the rest were addicts/alcoholics. The law gave courts broad leeway to sentence any woman to the Home for having any connection at all with prostitution or merely being considered a “common drunkard.” One woman was reportedly 67 years old, and all were charged with simply vagrancy.5

Much was later made by critics about the 67 year-old; “When do ‘wild women’ cease being wild?” taunted the Index-Tribune, although she could well have been a bordello’s madam – and the law specifically mentioned, “any women…keeping a house of ill fame.” Others would accuse Morse of padding the rolls. A member of the State Board of Control shared with the I-T a letter where he made the unlikely charge that federal prisons were in cahoots with Morse, and wardens were lending her convicts in order to polish up her budget:

| …The institution never had many of the class of women for which it was intended, namely prostitutes or street walkers. When criticism arose because the institution was costing about $1100 per capital per year, the superintendent ‘borrowed’ a number of narcotic addicts who were under federal conviction, thinking that by increasing the inmates the per capita rate would be decreased… |

Hammered by critics, by the end of 1922 – when the Home had been active only about seven months – a bitter fight was already underway to keep it open for even another year.

The Sacramento Bee came out strongly against it, as did bureaucrats and politicians with influence and oversight responsibilities. Themes emerged: The women should be treated in regular state hospitals or imprisoned; the property should be used for a more deserving cause; if the women’s clubs wanted the Home so badly they should pay for it and make it their charity. On the other side, the state League of Women Voters vowed to fight closure and many women’s clubs demanded the project even needed to be expanded. Some clubs pledged to raise money.

Governor Richardson’s recommendations for its 1923 budget was chopped down to about twenty percent of what he asked, which clearly wasn’t enough to continue operations. Morse went to Sacramento ready to surrender. Then this happened:

| Just after Miss Blanche Morse, superintendent of the Sonoma prison farm for Delinquent Women, had finished telling the joint legislative committee holding hearing upon the Richardson budget that she was about to recommend temporary suspension of the institution, word was flashed over the wires telling of the total destruction of the home by fire. |

“Sonoma Valley’s beautiful landmark, The Castle, for 40 years nestled against the Buena Vista hills, is today a blackened ruins, for the building, since 1921 used to house women delinquents of the state of California, suddenly broke into flames Monday night at 6:15 and burned to the ground…” read the lede in the Sonoma Index-Tribune on March 17, 1923.

The fire began while the 65 inmates were starting supper and was well underway before a member of the Sebastiani family saw it from their house and called the fire department.

All managers were away that evening with Blanche Morse and the Home’s business manager in Sacramento and the farm manager off duty, leaving only a groundskeeper and attendants to cope with a life-threatening emergency. Everyone sought shelter in the hospital; even though it was made of brick, there must have been fear and panic as the immense building next to them blazed away for three hours. All of their clothing and personal items in their top floor dormitory were lost.

The Sonoma and Boyes Springs fire departments responded. The Index-Tribune wrote, “…When the fire departments arrived they found the farm water supply of little value owing to repairs which were being made to the reservoir, so the Sonoma engine therefore pulled water from a nearby creek. Despite four streams playing on the building it burned like tinder.”

|

| A later view of the mansion at Buena Vista, probably c. 1920. Photo courtesy Sonoma County Library |

The I-T rushed to suggest inmates had set the fire. A few years later the paper fleshed out the rumor in more detail: “It was common talk in Sonoma that an inmate boasted she had set the fire — the last of three conflagrations in the building — had locked the door where the flames were started and thrown the key out of the window…” Today it seems commonly believed that it was indeed arson.

But less than three weeks earlier there had been a major fire because of a “defective flue” (no details were ever provided). So serious was the incident that the Sonoma firemen had to chop several holes in the roof to get it under control. Repairs were ordered and the very day of the big fire, a local contractor was working on the problem flue. It seems far more likely the building was destroyed because a workman accidentally did something (knocked loose creosote buildup?) which caused a chimney fire the next time the fireplace was used.

Although the old mansion was destroyed, the state still owned the land and its valuable hospital. Led by indomitable Mrs. Aaron Schloss – the feminist who almost singlehanded turned California clubwomen into a formidable political bloc – the women’s club organizations immediately began to lobby hard for a new building so the Home could resume its purpose.

The pushback was fierce, critical of not only rebuilding any facility for women at Buena Vista but continuing the project at all. Gilbert B. Daniels, State Board of Control chairman said, “If it is the last thing I do, I’ll oppose that farm. It is a fad.” The director of the State Department of Institutions called it a boondoggle and a failed experiment. And as always, from the Index-Tribune’s columns plentiful sexism oozed: The law only passed originally because legislators were “stampeded by the petticoat brigade” and the only people who wanted the Home to reopen were “women theorists and job chasers.”

But even though the governor wanted to give it funding for another year at least, the California Industrial Farm for Women ceased to exist on June 30, 1923.

Over the next two years many ideas of what to do with the hospital were floated. The Sonoma County Federation of Women’s Clubs wanted it to be a children’s TB sanitarium. A veteran’s home was suggested as well as an orphanage for children of WWI vets run by the American Legion, which was proposed by Jack London’s sister Mrs. Eliza Shepard, state president of the women’s auxiliary. In 1924 it unofficially became sort of an annex of the nearby Sonoma State Home at Eldridge, when they housed 35 epileptic boys at the hospital.

The women’s club movement was split; some moved on to lobby for new female quarters at San Quentin (it was built in 1927).6 But in 1925, there was a last push by some clubwomen to revive a woman-only institution at Buena Vista.

A bill was introduced to construct an actual prison building for a “California Women’s Reformatory.” Housed there would be women felons, drug addicts, and “women committed under the provision of the act establishing the California Industrial Farm for Women.” A group from Sonoma county went to the capitol to lobby against it; some, like Eliza Shepard, thought such a place was a good idea, but just didn’t want it in our county. The party rehashed all the old horror stories about inmates escaping and causing havoc – until a legislator produced a letter from Sonoma City Marshal Albertson “denying that wild women had ever given anyone trouble.”

A test vote easily passed in the Assembly and according to the I-T, “Senators had apparently pledged support to not antagonize ‘the army of women lobbying for this bill’ and hoped the governor would veto it.” He obliged, and that was that.

Whatever anyone’s opinion of the Home’s purpose, its ending was tragic, particularly the terrible loss of that building, which was the largest and most palatial home ever built in Sonoma county. It’s also a shame we don’t know what really went on there, except through the spittle-flecked pages of the Sonoma Index-Tribune. Blanche Morse was required to keep detailed reports on all the inmates, so there are probably reams of data in the state archives. Maybe there’s a grad student out there looking for an interesting thesis topic.

Morse certainly thought it was successful; during her testimony on the day of the fire she said, “so far 60 per cent of those who had been freed had made good in the occupations to which they were sent.”

“…I believe that if a 15 per cent average of those who make good can be maintained in the future we will be doing extremely well…I do not think it reasonable to expect a woman who has lived the life of the streets for twenty years to completely reform in one year.”

For the 65 women who were at the Home following the big fire, however, there would be only incarceration – and worse. Before winding up this dismal coda to our story, remember the women were sent there for up to five years only on the fuzzy charge of vagrancy after having been denied their basic constitutional rights. Nor had a county “lunacy commission” been convened to determine whether any of them were mentally unfit.

As they couldn’t remain confined in the small hospital for long, the plan was to gradually resettle them at Eldridge. Two days after the disaster, four of the inmates sent there escaped and had to be recaptured by long-suffering Deputy Ryan. The same day he was called to the hospital, where the women were said (by the Index-Tribune) to be rioting. Five of them were carted to the Napa State Hospital. A five year commitment to an asylum would be no fun, but it was the women taken to Eldridge who most deserve pity.

By 1923, the Sonoma State Home had become virtually a factory operation of forced sterilization under superintendent Dr. Fred O. Butler, a firm believer in eugenics (see, “SONOMA COUNTY AND EUGENICS“). Between 1919 and 1949 about 5,400 were sterilized there – “We are not sterilizing, in my opinion, fast enough,” Butler said. And in his early years there was also a marked shift in the types of patients arriving at Eldridge: Instead of the “feeble-minded children” of the old days, a large proportion of the inmates were now female “sexual delinquents.”7

Just as the legislature in 1919 gave the state broad powers over delinquent women, they also authorized forced sterilization of inmates, including any “recidivist has been twice convicted for sexual offenses, or three times for any other crime in any state or country” (emphasis mine). A later amendment extended it to include, “…those suffering from perversion or marked departures from normal mentality, or from diseases of a syphilitic nature.” In other words, there can be no doubt that all of the Buena Vista women were sterilized – the only question is whether Butler also performed some of the other horrific experimental genital surgeries which were described in part one.

There’s never been a book written about the Home, or even an article (well, until now). Was it was successful rehab program far ahead of its time or just a misguided social experiment by do-gooders? Or something in between?

What’s certain, however, is it ended up badly for almost all of the women. Picked off the streets on some misdemeanor – soliciting, drunkenness, homelessness – they expected a fine and a few days in county jail. Instead they were sent to state prison (albeit a beautiful prison) indefinitely. And then after a few weeks or months a few found themselves confined to the madhouse, while most of them discovered the punishment for their minor crimes would be going under Dr. Butler’s eager knives.

1 This era was the start of America’s faith that an “IQ test” objectively measured intelligence with scientific precision, although we now recognize the exam was filled with cultural and racial bias – see my discussion here. Using such quack methodology, a 1917 study by the San Francisco Dept. of Health claimed about 2 out of 3 prostitutes examined were “feeble-minded” or “borderline.”

2 Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom by Wendy Kline; University of California Press 2005, pg. 47. Although I could find no newspaper articles mentioning the 110 women arrived, Kline is the authority on Eldridge for that era and had access to the institution’s records.

3 Sonoma Index-Tribune clippings in the scrapbook sometimes were reprints of articles from the Sacramento Bee and Bay Area newspapers, but all clips are consistently negative about the Home. An op/ed in the January 13, 1923 I-T suggests the other regional newspaper, the Sonoma Valley Expositor, was in support of the Home, but nothing from that paper was included in the scrapbook. Scattered issues of the Expositor from the early 1920s only can be found at the state library in Sacramento.

4 Gender and the Business of Americanization: A Study of the Mobilized Women of Berkeley by Rana Razek; Ex Post Facto/SFSU; 2013 (PDF)

5 From the March 17, 1923 Sonoma Index-Tribune: “Senator Walter McDonald of San Francisco declared that he did not believe the women were being treated fairly in that they can be sentence to the home for a term not to exceed five years, while men charged with vagrancy, the charge under which all commitments have been made to the home, can receive only six months in the county jails of the state.”

6 A Germ of Goodness: The California State Prison System, 1851-1944 by Shelley Bookspan, University of Nebraska Press, 1991; pg. 81

7 op. cit. Building a Better Race, pg. 54

|

| Collage of Sonoma Index-Tribune headlines, 1922-1925 |

MANAGERS ASKED TO COOPERATEWould Establish an Institution for High Grade Morons at the Estate of the Sonoma State Home.Representatives of the Probation Committee of San Francisco appeared before the board of managers of the Sonoma State Home at their meeting at Eldridge on Wednesday and asked the board for co-operation in the providing of cottages and a place for about three hundred delinquent women from the bay cities. They belong to a class designated as morons.

This step is said to be in the nature of an emergency measure on account of the unusual conditions that have arisen incident to the health protection of soldiers in camp in and around San Francisco. But long before the recent conditions that have arisen this matters was discussed at Eldridge.

The board of managers took no definite action in the premises other than promising whatever co-operation th«y could give. The delegation appearing before the board of managers wanted cottages built on the home grounds in some suitable location. There is no fund available for such buildings in the hands of the state at the present time and even though there was an available fund it is doubtful if the home estate is the proper place for an additional institution as that suggested.

– Press Democrat, November 16 1917

MUCH BUILDING AT STATE HOMENew Cottages for Female Delinquents to Be Rushed to Completion at an Early Date: New Laundry Building and Bakeshop Are Also to Be Built Right Away.The Sonoma State Home at Eldridge will be the scene of much building for several months for there are a large cottage and the new laundry and the bake shop to he erected.

Work on the new cottage, which will house one hundred, has been commenced and it will be rushed to completion. As stated it will be used, for the present at any rate, as a moron colony, to which young women delinquents, will be committed from San Francisco and the other big centers. The matter was explained in these columns several days ago. From Manager Rolfe L. Thompson it was learned Wednesday that the work ot this building is to be rushed to completion right away.

The board of managers on Wednesday selected the sites for the laundry building and the bake shop. The two latter buildings will supply a long felt need at the home. They are very necessary buildings.

The State Board of Control has placed Business Manager William T Suttenfleld in charge of the construction work on the buildings. He is a splendidly capable man and is always so busy working for the interests of the institution and the state that one more little burden makes little difference to him. “Bill” has been at the Sonoma State Home for almost a score of years.

– Press Democrat, March 14 1918

OPPOSITION TO MORON COLONYMany People in Sonoma Valley and the Town Object to Having the Colony Located With the Sonoma State Home for the Feeble Minded.The people of the Sonoma valley and the old Mission Town of Sonoma are not taking very kindly to the idea of locating the “Moron Colony” at the Sonoma State Home for the Feeble Minded. Many protests are being heard and it is likely that a largely signed petition will be presented to the authorities, asking that the plan be not carried out.

In last Saturday’s Sonoma “Index-Tribune,” editorially, there was a strong protest against the additional institution being located in the Sonoma valley.

As stated in the Press Democrat some days ago the board of managers literally had the location of the colony at the home thrust upon them is an emergency measure, backed by the state and national administration, it was said.

There is considerable objection to having the moron colony established in connection with the feeble minded home, in addition to having it in the valley at all. The late medical superintendent. Dr. William J. G. Dawson, was bitterly opposed to having an institution for the care of socially outcast young women at Eldridge and shortly before his death again expressed his views.

There is said to be one ray of hope for the objectors and that is the one cottage that is to be built will only provide temporary relief for a very few of the young women who are to be removed from the big centres, particularly from the borders of army cantonments, as one building will afford only little room for conditions that are said to exist. It is knowm that the board of managers were reluctant to take in the new institution the grounds of the home, even as an emergency measure, but the showing made by the state authorities was so strong as a necessary war emergency measure that they withdrew their opposition.

– Press Democrat, March 19 1918

OBJECT TO LOCATION OF STATE HOMEThe Sonoma Valley is still seething in protest against the establishment of the home for moron women and girls at Eldridge. Dr. A. M. Thompson, president of the commerce chamber, voices his protest in the following words:

“My protest not only goes against the location of the new institution in the Sonoma Valley, but particularly having it at the home for the feeble-minded. The late Dr. Dawson, the medical superintendent for many years, held the same views as I do–that the feeble-minded home had its problems to take care of without having any new ones.”

– Petaluma Courier, March 22, 1918

MAKES PLEA FOR FEEBLEMINDEDSenator Slater Leads Opposition to Proposed New Penal Institution or Farm For Delinquent Women and Urges More Room for Unfortunates“Before we take on a horde of other dependents I believe the State should take care of those who are already dependent and must and should have attention first.” said Senator Slater before the Finance and Ways and Means Committee last night, when the proposed new penal institution or farm for delinquent women was discussed.

“At the Sonoma State Home for the Feeble Minded we have a waiting list of 447, and many of these cases are deserving in the fullest sense. In fact many of them heart-breaking in their need right now. Take the $250,000 you are asking for this women’s farm vision and build more cottages to house the dependents waiting, and who have been waiting for years to get the help and protection the State should offer.

“If the finances were available the new project, over which I have no quarrel as to its probable good, might be considered. But the State must stop somewhere when we are at our wits ends over taxes and finances, and particularly when we have hundreds of feeble-minded and other dependents who are crying for aid. Let’s care for these first. That is my idea, and I am sincere in my expression on this subject,” said Slater. Senators Ingram. Sharkey and others, and Assemblymen Salahnn. Stanley Brown, Stevens,. Madison and others agreed with Slater.

– Press Democrat, March 2 1919

Club Women From Various Parts Of County Assemble At Interesting Petaluma SessionThe other speakers from abroad were Miss Blanche Morse of Berkeley, former corresponding secretary of the State Federation, and at present executive secretary of the State Industrial Farm Commission…Miss Morse, who will be the superintendent of the Industrial Farm which is to be situated in this county at “The Castle” the Kate Johnson estate near Sonoma, told of the needs for the home and the plans of the commission in reference to it. She met the objections raised in connection with the project and asked the cooperation or at least the interest of the Sonoma county women in the scheme when once it is under way.

– Press Democrat, October 3, 1920

S. F. POLICE HEAD AT NEW STATE HOMEIndustrial Farm For Women, Near Sonoma, Not to Be Like a Prison; There Will Be No Bars.The following article about the new industrial farm for women located near Sonoma appeared in Monday’s San Francisco Bulletin. It was written by Dolores Waldorf:

A prison that is not a prison, a jail without bars, an institution that spurns the stigma of the name, stands in the hills of Sonoma county today, waiting for its first inmate. It is to be known as the California industrial farm for women, a place where delinquent women over 18 years of age may make a fight to regain a normal view of life and where they may prepare themselves to face the world after their term ha* been served. The sentences will vary from six months to five years.

The house and surroundings were inspected Saturday hy Police Judges Sylvain Lazarus and Lile T. Jacks, Chief of Police Daniel O’Brlen and Captain of Detectives Duncan Matheson. They expressed their approval in emphatic terms and seemed to think that it offered the solution to one of the greatest problems before the criminal courts today.

In 1919 the legislature passed a bill providing for such a place and appropriated $150,000 to start work. Nothing could be done until the board was chosen, however. and in 1920 the governor appointed…

680 ACRES IN FARM

Since then men have been steady at work carrying out the plans. The Kate Johnson home, two miles east of Sonoma was purchased for $50,000. This included 680 acres of land mostly under cultivation. The house itself is a huge, rambling mansion with spacious rooms and great hallways. Though the whole place has been completely renovated new plumbing installed and modern conveniences added in the laundry, there is an air of ancient and settled serenity about it. The house will accommodate about seventy women.

Captain of Detectives Duncan Matheson, who attended to the purchasing and remodeling of the home, said of it during the inspection Saturday: “In choosing, a place, we had to think of two things Isolation and cheerfulness. Who couldn’t he cheerful with these hills around them?”

Miss Blanche Morse, recently ot Berkeley, and an active worker in all suffrage and reform movements, has been appointed superintendent of the farm.

SANS THE LOCKSTEP

“We are going to give the inmates work to do,” she said, “but we are not going to apply the institutional idea and make them do it to bells and march-time. Each woman will help around the house in some way.” Miss Jessie Wheelan of the Southern California hospital for the insane, is to have charge ot the indoor work.

– Press Democrat, December 20, 1921