In other times and places they may have been considered twin villages. The two communities brushed against each other, each with a mercantile district, its own places of worship and sometimes populations of roughly the same size. But never did they have equal standing, which is because one of those communities was entirely Chinese immigrants and this was the American West in the 19th century. Specifically, this was Sebastopol and its Chinatown. Its two Chinatowns, actually.

Before diving in, it pains me to admit the tale you’re about to read is incomplete. I’ve pecked away at the history of this fascinating lost world for ages, returning to it whenever another historic newspaper or trove of other data came online. But it’s been a while since anything really significant surfaced; it looks like some sections of the puzzle – critically important sections, at that – will always be missing. So here I’ve put together what I have, in the hope that someday a family memoir, a dusty photo album or a history by one of San Francisco’s Six Companies will appear, allowing scholars of Chinese culture in the West to cement more parts of the picture together.

This project began over seven years ago after finding a remark by West County historian Bill Borba: “Sebastopol had two Chinatowns that must have had in the neighborhood of 200-300 Chinese in them…” Sure enough, I found the fire maps which showed the village seemed to have two Chinese enclaves about a block apart. I soon learned this was a very unusual situation.

| – | – |

“JOHN CHINAMAN” COMES TO SONOMA The earliest Chinese immigrants probably arrived in Sonoma county around 1855, as they did in Marin; the 1860 census shows about forty, all but a handful living in the town of Sonoma. During this decade the local newspapers fed readers a steady diet of racist stories about the doings of “John Chinaman” in San Francisco or the Gold Country, but little about the men living here. A rare 1868 item from the Santa Rosa paper told of a Chinese man who reported being robbed by two boys – but “several white persons near by when the alleged act was committed” claimed he was lying, so the case was dropped. By the 1870 census the Chinese population had grown tenfold; 470 men were counted in the county overall with over half (280) living in Petaluma. Salt Point was the third largest Chinese group with 96 (mainly logging camps at Timber Cove and Duncan’s Mills). Five were listed in Bloomfield. In 1871, California Pacific railroad brought in a crew of over a thousand Chinese laborers to begin work on a rail line between Santa Rosa and Cloverdale. Judging by the number of newspaper reports, this decade was by far the most violent for Chinese immigrants, with multiple reports of beatings, shootings and a trend of young white boys shooting them in the face. The most disturbing incidents were when hunters found a body in the Laguna; although the Coroner’s Jury met there and believed the man had been murdered, there was no further investigation and the remains were buried at the site following the verdict. Near Bloomfield, an immigrant supposedly attempted suicide by cutting his throat, followed by splitting his head open with an axe. When the Coroner’s Jury arrived at the scene they found the body some distance away in a potato field; it was decided the injured man stumbled there on his own and there was no foul play involved in any of it. The body remained lying in the field for several days. Although the 1880 census missed the entire Chinese community at Bloomfield (although there were eight counted in Valley Ford), there were still 901 enumerated in the county, with Sonoma City, Santa Rosa and Petaluma having the largest populations, in that order. The population of the Analy Township was 1,380 with 37 Chinese immigrants, and Sebastopol had 197 residents with only three from China. Only summaries of the 1890 census exist, but there were 1,173 identified as Chinese in the entire county with 231 in the Analy Township (there was no breakout for Sebastopol), slightly behind Santa Rosa’s leading count of 277. |

Was this a single community split between different streets or were these really two separate Chinatowns? Evidence points both ways. Until the last buildings were razed in 1943 1945, the Sebastopol newspaper referred to one as New (or Barnes’) Chinatown and the other as Old (or Brown’s) Chinatown. Each had its own “joss house” (a place of worship) which I’m told was never seen in a town so small. (By contrast, there was no joss house at all in Santa Rosa, although we know there was a room used as a temple.) But did one group have better status, more wealth than the other? Those and other loose threads are tugged below.

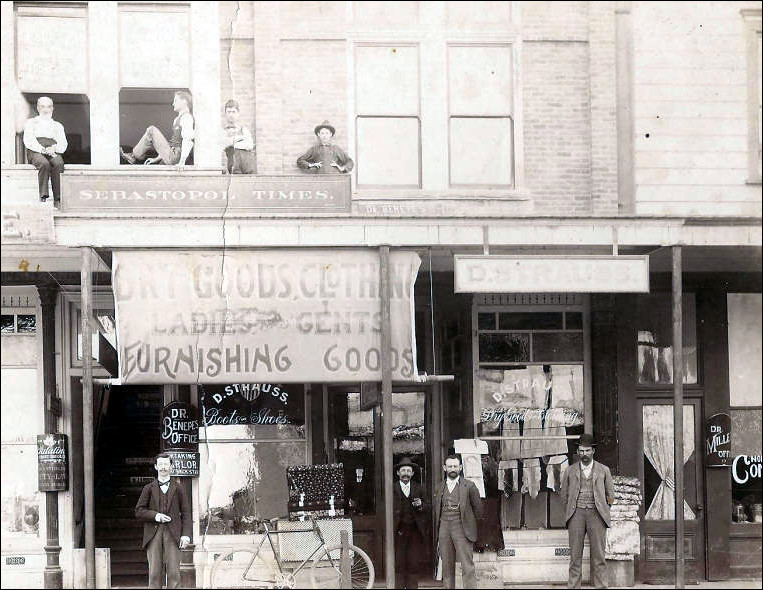

Nor do we have any images of the Chinatowns except for grainy photos taken before it was to be demolished. There are no known pictures of any residents – the man seen at the top of this article is from Arnold Genthe’s book on San Francisco’s Chinatown at around the turn of the century.

Even worse, we don’t have an accurate view of how many people were living there at any particular time. Old census data was often problematic when it came to enumerating ethnic minorities, possibly because of racism or language barriers. In the 1880 census there were no Chinese counted in Bloomfield, for example, although there were probably hundreds living there; other census takers in the county that year didn’t make much of an effort to record Chinese names with any accuracy, filling in the census forms with meaningless stubs such as “Lee,” “ah Gus,” “Hong Kong,” or “Sing.” Complicating matters, the census was usually taken during the summer months when Chinese ag workers might be away from where they lived most of the year, dispersed on farms or among work crews where they could be overlooked (or hidden). A more specific example of these problems is below.

Our story begins in 1885, although newspapers had occasionally mentioned Chinese men in Sebastopol over the previous decade. (Most news about early Sebastopol comes from the Petaluma Argus, as older 19th century Santa Rosa papers mostly ignored the village.) That year Aaron Barnes announced he was moving “his China houses” off Main Street; it didn’t happen for several years, as the 1888 fire map shown below still showed a Chinatown with about a dozen buildings, roughly across the street from today’s Copperfield’s store.

Aaron Barnes (1816-1897) was a farmer/real estate investor who owned several lots around downtown Sebastopol, most notably the large corner at Petaluma Ave. and (modern) Highway 12, where the CVS and Benedetti Tire now stand. He had a quirky life, which earned him a profile in “SEBASTOPOL WAS ALWAYS QUIRKY,” but it was never explained why he seemed to have so much devotion to his Chinese tenants. There’s a family story that he liked them better than the white townsfolk because a church had done something to offend him and his first wife. But his cause of death was diagnosed as constipation, which might seem unusual because the cure-all tonics during his era were usually strong laxatives mixed with alcohol. That condition is also famously a side-effect from chronic use of opium.

The situation changed quickly and dangerously in the first weeks of 1886. Anti-Chinese vigilante committees had been running amok on the West Coast for months, terrorizing immigrants into leaving their communities under threats of death. While Sonoma County locals were chanting the popular “Chinese must go” mantra, there was no violence or anti-Chinese activism here. But when members of Petaluma’s Wickersham family were brutally killed in mid-January and their Chinese cook was accused of the deed, anti-Chinese Leagues sprouted overnight in every Sonoma community with intent to expel them. For in-depth coverage on that story, see “THE YEAR OF THE ANTI-CHINESE LEAGUE.”

Before the end of that January there was a trickle of Chinese coming into Santa Rosa from Cloverdale, Healdsburg and other points north. Some were passing through on their way to San Francisco, but many apparently were lingering in town to see how the situation would develop – the Democrat newspaper reported there were over 600 Chinese in Santa Rosa as the month ended. Sebastopol’s Chinatown swelled at the same time. The correspondent for the Argus wrote “the town has about 360 Chinese and they outnumber about 250 whites.” In the next few weeks, the Chinese population of Sebastopol peaked at an estimated 400-450.

| – | – |

BLOOMFIELD’S “PIGTAIL ALLEY” Several locations have been identified but none are documented by archaeology; camps were said to be at the current location of Emma Herbert Memorial Park and near the intersection of Roblar Road and Valley Ford Road. Several buildings were rented along Main Street (now Bloomfield Road), with “Pigtail Alley” somewhere nearby. This was probably their Chinatown; a Chinese butcher shop and laundry are mentioned in articles below, so it’s fairly safe to assume there was a business area similar in size to Sebastopol. In February 1886 an Anti-Chinese Committee was formed in Bloomfield, same as in all other Sonoma County communities. But the situation was different, due to the size of the Chinese community (“there is no town in the state, of its size, where there are so many Chinese” – Sonoma Democrat) and because some Bloomfielders were inclined to vigilante activity. An unsuccessful attempt was made to blow up a Chinese laundry (“result, a lot of frightened Chinamen and a shattered floor”) and a spring that supplied water was salted. That October – months after the anti-Chinese fervor had sputtered out in Santa Rosa and other places – the Argus reported that vigilantes “…have AGAIN [emphasis mine] taken the law into their own hands and have forcibly ejected them from the town.” Predictably, the farmers found themselves short-handed when potato harvest season arrived in 1887: “It is impossible to get enough white hands. Chinamen are scarce and disposed to boycott the Bloomfield country, from which they were driven a year since.” Potato blight damaged much of the crop in 1889 and by 1891 there were only about 100 acres still planted in potatoes, most of the land converted to dairy pastures. |

Many who sought refuge in Sebastopol presumably were coming from nearby Bloomfield, which had the largest sustained Chinese community in the county. Bloomfield was also the site of the only local vigilante activity, which continued for months (see sidebar). But as winter turned into spring even the Chinatowns in Sebastopol and Santa Rosa shrunk greatly, although it’s most likely because of residents melting away into the countryside to take their customary farm jobs now that growing season approached.

After a year passed there was no sign the anti-Chinese furor had any lasting effect in Sebastopol (“there are more Chinamen in Sebastopol to the square foot than in any American town that we know of” – Argus). The Petaluma paper reported boys – and women from Santa Rosa – were coming to the village’s Chinatown to smoke opium, a matter of some irritation to the townsfolk.

The first possible sighting of a second Chinatown appears in 1889: “The Chinese have built a Joss house in town.” That it was built by the Chinese themselves (or perhaps, paid for by them) suggests Barnes was not involved, as he apparently always hired contractors.

This other Chinatown was on property owned by John Brown, like Barnes a farmer/real estate investor, although on a much larger scale – he had some 1,400 acres on the east end of Sebastopol which he leased to others, making him the second largest landowner in the area (the Walker ranch was larger). His cottage still exists on the edge of town and is currently home to the Animal Kingdom Veterinary Hospital.

That became known as Old Chinatown. Then 15 months later, in early 1891, New Chinatown started to appear: “Elliot & Berry are building a fine Joss House for the Chinamen.” Later that year, “a number of China houses are in course of erection on the corner of Petaluma and Bodega avenues by Mr. Aaron Barnes, and the Joss house which has been located near Mr. Barnes’ residence has been moved to the same lot.” (It never ceases to amaze me that they moved houses around like dominoes back then.) To be clear: This Chinatown occupied the entire footprint of the modern CVS and its parking lot.

And so Sebastopol became accustomed to having two Chinatowns in its backyard. One of the rare items in the Sebastopol paper that mentions both describes the comic 1898 efforts to restrain a bull running through the town: “…he concluded to have some noodle soup and charged the restaurant in Barnes’ Chinatown. The boss cook banged a big tin pan against the noodle pot with such effect that his lordship wheeled for Brown’s Chinatown. Whether he wanted to hit the pipe or was looking for a game of fan tan is not known…”

Another episode from the same year shows how fairly the town treated their Chinese residents. During Lunar New Year celebrations Deputy Constable Woodward attempted a little extortion, demanding $5 from each merchant who was exploding firecrackers. As there was no such thing as a firecracker tax, two men began arguing with Woodward; that turned into a fight with the cop pistol-whipping a young man named Ah Woy, who filed a complaint against the constable. During the court hearing a few days later about a dozen Chinese witnesses testified. Woodward’s defense was that he only asked Woy to quiet down and was attacked by Woy while trying to assist him to go indoors. “Some of the Chinese witnesses, however, did not seem to agree with the constable’s version of the fracas,” the Press Democrat reported. “Some of them of the ‘little bit Engleesh’ persuasion just looked daggers at Mr. Woodward.” The court fined Woodward $20 for battery and dismissed Woodward’s assault charge against Woy.

There was probably no happier year in those places than 1898. There were now children in the community and there was a wedding:

| “A Chinese bride! A Chinese bride!” The word was passed like wildfire among the crowd at the Donahue depot as the ten o’clock train on the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad slowed up there Wednesday morning. Instantly everybody was anxious to catch a glimpse of the celestial maiden, clad in the most fantastic of bridal costumes…When the bride and her party arrived at Sebastopol they were given a great reception by scores of Chinese. In a gaily decorated vehicle adorned with flags and Chinese lanterns, the bride was escorted through the streets. Later in the day the marriage took place amid much pomp. the groom was a “heap high tone” Chinaman employed on the Knowles ranch near Sebastopol. |

Less happy was 1899; almost all of Barnes’ Chinatown burned down, wiping out 15 buildings including stores, boarding houses, the Joss house and their Masonic hall. There was great concern during the fire because the winds were blowing towards town and no one knew where their hook and ladder truck was (it was found on a vacant lot, someone having borrowed it for personal use). As Aaron Barnes was now deceased, it was unclear whether his son Henry would rebuild. By the end of the year it was reconstructed about 75 feet further east away from Petaluma Ave. One merchant, Quong Wah, was wealthy enough to build his own place.

In the summer of 1900 the census taker found 77 Chinese in and around Sebastopol, two of them women. Most were in small knots of 3-5 laborers living on farms but about a third were in the Chinatowns, which now had two groceries, two merchandise stores, three laundries and a barber. The two Chinatowns were still about equal size on the 1903 map. John A. Brown died in 1905 and the property passed to his daughter, Birdie, who continued making improvements into the 1920s. It was no longer called Old Chinatown/Brown’s Chinatown but “China Alley.”

Fast-forward ahead another decade; the 1910 census is the only one which recognized two Chinatowns, with about 25 people living in each. Seven were female and nine were born in California. Kim Lee owned a laundry; there were five grocers and eight other stores, which seems like a lot, if there were really only fifty people.

And now we come to the 1920s; there’s a druggist who has his own store, two salesmen, and sixteen people under age 20, with two dozen people born in California. The census says there are 84 living in “China Town.” Except that’s apparently not really true. To (somewhat) repeat myself: When it comes to the Chinese, the census data is like a house of cards – touch it lightly and it all falls apart.

Meet Johnny Ginn. He was an old man in the early 1970s when he was interviewed by sociologists collecting oral histories of the Chinese experience in California.* He was the only one interviewed who spoke about Sebastopol, having grown up around there; that 1898 story about the Chinese bride concerned his mother.

Johnny’s father was named Ginn Wall and as the wedding item states, he worked on the Knowles ranch near Sebastopol. But according to the 1900 census, there were no Chinese living on or near the William H. Knowles ranch. Same for 1910, 1920. In fact, Johnny and his parents can’t be spotted in any census at all, as far as I can tell, and they were not alone in being overlooked. As he told the researchers, “There were about three hundred Chinese farmworkers up there, and they were all old men…and except for my mother, not a single woman. That was the whole Chinese settlement in Sebastopol.”

Johnny’s mother died in 1929 and his father went broke being a tenant farmer. After saving for the next six years they finally had the $600 to send Ginn Wall back to China by himself. Johnny told the researchers he realized that the farm settlement in Sebastopol was dying:

| All those old guys thought about was how they wanted to go back to China. But there’s only about six months work in the year on apples, so they never saved a thing. And the only other thing besides work was gambling. Gambling was the social life, and gambling was the pastime. Everybody hoped to make a few bucks so they could go home in the easy way. The others lost their money and got stuck from year to year. |

By then in the mid-1930s it was a bachelor society of elderly men. There was nothing still keeping him there, so Johnny became a migrant worker.

Our last glimpse of the Chinatowns comes from the 1929 map, which shows the one on Brown Ave. (now Brown St.) in slow decline, while Barnes Ave. has slightly grown. The census in the following year again had a low headcount of 54 residents, but there was also now the eight-member Gin Hop family with their own house on Pitt Ave. (He was a China-born merchant and presumably no relation to Ginn Wall.)

| – | – | DOWNLOADPDF file of transcribed sources discussed in this article (26 pages) |

Of most interest to historians is the 1929 map appearance of a Tong Hall at the southernmost end, which raises several intriguing questions. It’s possible it had been there for years, but escaped notice of white cartographers who didn’t understand it possibly represented the foothold of a crime gang. In the late 1890s the Sebastopol paper had several items about highbinders (tong enforcers, sometimes hit men) being in town and a man who supposedly was a local highbinder was himself killed there in 1899. Although the separate Chinatowns began as protectorates of Messrs. Barnes and Brown, it’s possible they soon came under the control of rival tongs. This would explain why two joss houses were sustained the entire time. (UPDATE: Most tongs were not criminal, particularly at this late date.)

It all came to an end in 1943, when Sebastopol condemned the last buildings on Barnes ave. as fire hazards. Press Democrat reporter Pete Johnson described the place as “ghostlike,” although there were some people still living there. A few remained in Brown’s Chinatown until August, 1945 when that district was likewise condemned.

The last celebration of Chinese New Year was apparently 1932 and it was a low-key affair, the usual gaiety dampened by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria a few months earlier. “Chinese and Japanese in the settlement here are said to exchange nothing but short greetings, but the situation isn’t acute,” the Sebastopol Times reported. Only a few gathered at the joss house to celebrate because only a few were still around. “Old-timers in the Chinatown here estimate their number to be less than 70…about one-fourth of the population several years ago,” said the Times, the paper at last acknowledging the true size of the historic community.

But earlier New Year celebrations there were always happy times, regardless of their pitiable situations, and it was also the only time of the year when the Sebastopol gwáilóu came over to visit with them. Let’s end our survey with a peek at the celebration in 1920:

| Wednesday noon in front of the joss house several strings of fire crackers, each over thirty feet in length, were exploded, much to the delight of Sebastopol’s boyhood. The Chinese had erected a high tripod on which they suspended the long strings of fire crackers by means of a pulley, but the first string had hardly been ignited when the tripod collapsed and the entire string exploded at once, much to the dismay of the Chinese…The rest of the fire crackers were more successful. All afternoon the tom toms and cymbals were kept busy by the Chinese musicians who were stationed in the joss house. |

| * Longtime Californ’: A Documentary Study of an American Chinatown; Victor Nee and Brett De Bary; 1986; pp. 25-29 |