It seems everyone who knew Ed Mannion has a story about him – which is perfectly fine, as he had lots of stories of his own to tell. About a century’s worth, in fact.

Until he died in 1991, Mannion was Petaluma’s unofficial historian and best known for his weekly “Rear-View Mirror” column in the Argus-Courier, although it ran less than four years and didn’t even appear all weeks. He filed his last column the day President Kennedy was killed; why he stopped wasn’t explained.

But Ed Mannion left behind more of a footprint than just “Mirror” (as he called it). He was writing about local history years before the column and years after; he assembled an enormous collection of rare documents and photographs which became the foundation of the library’s Petaluma History Room. And if Ed the Historian isn’t enough to impress, take note he was also a key participant in the uphill fight against PG&E’s scheme to build a nuclear reactor at Bodega Head.

In the golden age of newspapering in the 1950s and 60s, his was likely a household name all over Sonoma county. In the golden age of the Internet today, his name is unknown. Google currently returns a measly 300-odd hits on him – mostly credits given in books for use of photos now in the library collection. Ed’s own voice is nowhere to be found online without access to a paid newspaper archive service (note: available on Sonoma county library computers). I never met Ed, sorry to say; even more, I regret never reading any of his stuff before this summer. To me, his name was just a nod in one of those footnotes.

What follows isn’t a biography of Ed or a critical review of his legacy – it’s just an appreciation and an introduction for 21st century readers. I’m only covering “Mirror” up through the end of 1961, which was the halfway point of its run. There is plenty left over for another article or three, including the story of how Ed and his co-conspirators were dumpster-diving (literally!) to rescue original historic photos which were then deemed worthless.

So for just a moment, pretend it’s 1954 and you’ve just strolled in to “Nick’s Chat & Chew” for lunch (the building’s even still there, at 600 Petaluma Blvd S.) and at the end of the counter is this funny-looking goofball telling stories. He’s snaggletoothed, his hair appears to have a mind of its own and his oversized black-rim glasses look like a failed effort to pull off a Clark Kent impersonation. But everybody around him is laughing – so let’s eavesdrop for a bit.

|

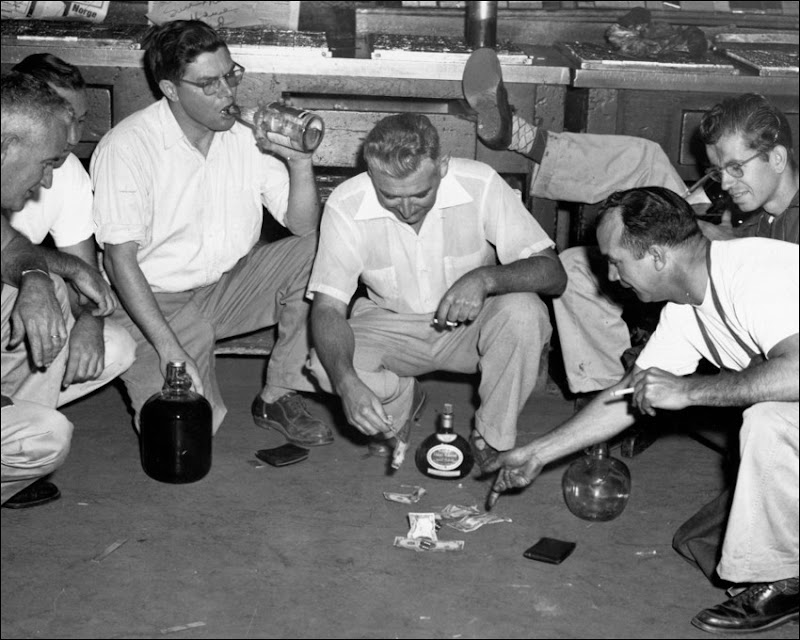

| Gag photo of the Argus-Courier back room staff shooting craps in 1955, with Ed Mannion drinking from a bottle. Photo courtesy Sonoma County Library |

“Yoiks! Another Columnist Enters the Ring” read the headline introducing Ed Mannion to Argus-Courier subscribers on Saturday, Feb. 6, 1954.

“News pickings sometimes tend to be a little slim for the week’s caboose edition, and the city editor has declared it Amateur Day instead of wasting good boiler plate. Or maybe, because I’m a linotype operation, he figures on saving copy paper by having this composed at the machine.”

Ed was indeed a linotype operator for the paper and would remain so for another thirty years, as well as a proud member of the Typographical Union. For those unfamiliar, these were the machines used to setup “hot lead” type via use of a bizarre keyboard. Anyone who was around such a shop (as I was as a child) will tell you the linotype operators were usually some of the most well-informed and erudite people you would ever meet – after all, they had to carefully read every line of the newspaper every day.

The Argus-Courier was a perfect home for Ed; it was a lively small town paper with a stable of must-read columnists including Lura Frati, Bob Wells and Bill Soberanes. By contrast, the Press Democrat at the time was a slog to get through, with pretensions that it was a major metropolitan daily and crammed to the margins with indifferent wire service items (least compelling headline ever: “Senate Debates Wool Bill”).

That incarnation of Ed’s column only lasted for a few issues but he remained familiar to readers through guest columns and mentions by the other writers. One story concerned the birthday of a friend who was an avid fisherman. Ed gave him a large rock with a note attached: “It is plain to see that you have been using the wrong fishing technique.” Also included was a clip from an 1879 paper, where it was reported that steelhead were so plentiful in Petaluma Creek that people were catching them by dropping rocks in the water.

Ed also contributed feature stories on the last ferry between Oakland and San Francisco (service resumed only after the 1989 quake) and the last ferry between San Rafael and Richmond. At home he had a small handpress he used to print up Christmas cards and the like, so for the final trip from San Rafael he handed out cards to fellow passengers: “This is to certify that the bearer is a member of the Anti-Bridge and Prevention of Cruelty fo Ferry Boats Society.” On the back was a vow “…to continue the fight against progress wherever it rears its ugly head.”

His fondness for gags like the rock and the cards (and a few more described below) can make it hard to take him seriously as a historian. Or was he just a “history buff”/collector? Did he want to educate readers by explaining how the pieces of history’s puzzle came together to form a picture – or was he just a guy who liked telling some really good stories?

Mannion called himself “a tramp printer who likes to read old newspapers,” which earns him my respect, revealing he tapped primary sources for information rather than repeating hand-me-down stories. He wrote so much there are probably mistakes which I don’t know enough to spot, but so far I’ve only found one glaring error – and to his credit, he found it himself some years later and corrected it.

It’s true he rarely tried to synthesize what he knew in the way “big H” historians do, but there’s not much room for that sort of thing in newspaper columns of only 600-1,200 words. His only real shot at long-form writing came with the historical portion of the 1955 centennial edition of Argus-Courier, which was edited and mostly written by him and his wife, Chris.

That section of the A-C is over 75 pages long (ignoring the full page ads) and is quite a remarkable work. Ed makes it clear at the beginning that they wanted to make something of interest to the casual reader but also good enough for serious historical research. “The fact remains that the usual way for newspapers to put out an anniversary issue is to use what passes for historical material as window dressing while the main emphasis is on jazzy promotion.” Amen to that, and let’s hope the Press Democrat resists the temptation to turn its sesquicentennial edition over to the Chamber of Commerce and Tourist Bureau.

In short, the August 17, 1955 edition of the Argus-Courier is permanently bookmarked in my browser; I’m certain I’ll keep returning to it as long as I’m writing about local history, as it covers the entire southern portion of Sonoma county. But Ed was still Ed, and there’s a bit of good natured humor in his intro to the section, which is framed as a “letter to mom.” They didn’t have room for everything, he explained, but they always tried to get area names right – even Valley Vista grammar school, which he thought “sounds like a title coined by a housing tract sub-divider’s wife who writes poetry.” Putting it all together was rugged, he wrote, but “I’ll come right out with the puppy-dog hope that a couple of readers will write in to say they liked our efforts.”

Enough credit cannot be given to Chris Mannion for her involvement with that task as well Ed’s other history projects. Besides having six pre-teen children (eventually, seven), she was sometimes his library researcher, cataloger of his archives and bric-a-brac, phone secretary and often accompanied him on interviews (while Ed was starstruck meeting Ida Lupino, she was somewhat less speechless in chatting up husband Howard Duff, showing off pictures of their kids). She was a part-time photographer for the paper and had a side business selling its photo reprints. In 1960 it was her, not Ed, who led the fight to save downtown Hill Plaza Park from being bulldozed for parking spaces. She died in 1971 at age 47.

After the paper’s centennial came Petaluma’s civic 100th birthday in 1958, and that was absolutely the best year for Ed Mannion’s adventures, which were tied in with E Clampus Vitus and fellow buff of history, Ed Fratini. This other Ed was the grounded yin to Mannion’s wilder yang. While Ed F. was diplomatically inviting San Francisco’s mayor to attend the Petaluma festivities, Ed M. was advertising in a San Francisco newspaper for a live, fighting grizzly bear.

|

| Ed Mannion in costume at a celebration during the late 1970s. The woman with her face turned away is his daughter, Mary. Photo: Sonoma County Library |

“Grizzly Bear wanted for bull and bear fight Main Street Petaluma, reply to the judge. McNeil Drive, Petaluma”, read the ad in a San Francisco paper a month before Petaluma centennial celebration in April, 1958.

“The judge” was Ed Mannion’s costumed Clamper persona; members of “The Ancient and Honorable Order of E Clampus Vitus” dress up to celebrate historic events. They also mount commemorative plaques and drink. They drink a lot.

As mentioned earlier, 1958 was also the 99th birthday for the Washoe House and the Clampers mounted a plaque at the famous roadhouse. That night they were up to their usual hijinks, including trying to push an old fire engine into the lobby of the Hotel Petaluma (it got wedged in the doorway and remained there for days). The events ended with a group dinner at the hotel – “a whole chicken for each man, and served on pitchforks,” as was promised.

Ed Mannion vowed to recreate an arena fight between a bull and grizzly bear that actually happened in 1861 at Haystack Landing. According to the Argus, the bear tried to escape and charged the ladies’ section of the bleachers. (“Ah, the good, pure days of yore,” Ed commented in a later “Mirror” column.)

The wire services picked up a photo of Ed wearing a sandwich sign promoting the “Bull and Bear Fight” on the back (the front showed a chicken pecking at a dancing Clamper) and interests were aroused. It made the front page of the paper in Virginia City and was widely blurbed in Bay Area papers. An incensed animal lover from Redwood City threatened to organize a statewide boycott of Petaluma. Ed finally wrote a disclaimer revealing it would really be just a couple of guys in costumes – but it’s not clear if the Clamper from Rough and Ready knew it would be a mock battle when he promised his pet badger, Solomon, would take on the winner.

Thus with costumes custom-made for the occasion, Smokey the Bear fought Ferdinand the Bull at Walnut Park in front of an appreciative crowd. In the third round the bull charged and the costume’s head fell off, after which the bear was declared the winner on account of decapitation.

The year 1958 was also when the Petaluma Fire Department sold its old ambulance. The two Eds came up with the $100 (or so) to buy it, with the view that a 1935 antique would be a “fine thing for parades and so on.” Its first outing was to a Clamper dinner at Beale Air Force Base near Marysville, where they arrived with wailing siren and flashing lights. Enroute they were pulled over only once, which is somewhat surprising because they were dressed in their pioneer getups and a cop doesn’t see an ambulance driven by ersatz 49ers every day.

Afterwards, one of the Clampers asked them for a lift into Marysville. Ed and Ed obliged, but when they arrived their passenger refused to leave unless they carried him into his favorite tavern on a stretcher.

“This was done,” wrote Bob Wells, “and it developed that the rider had many friends in the bar. All these had to be formally introduced.”

Finally on their way back to Petaluma through Napa county, the headlights began to fail. Mannion discovered he could jiggle wires under the dashboard to temporarily get them to flicker back on, but when they flickered off again he had a flashlight at the ready to shine through the windshield and keep Fratini from running them into a ditch.

And so we come to the debut of Rear-View Mirror on March 12, 1960.

While Ed Mannion could write in a concise news style as the subject demanded, most of his offerings are a happy and entertaining tour of whatever had his attention at the moment. Some columns read like a modern blog, as Ed digs through his cluttered desk in the den at their home at 1 Keller street, crowded with the seven kids, two cats and a dog named Scooter.

Reading “Mirror” is like touring Burbank’s garden – there’s lots to see and absorb. With hopes that Gentle Reader is not too weary of reading about all things Ed, here’s a bouquet of items from the first two years that are little-known (at least, to me) and quite interesting:

|

During the Civil War, Schluckebier’s store listed prices in both Union and Confederate money |

|

A letter about Petaluma schools in the 1870s recalled Professor Crowell’s tenure ended when he was gassed out by a prankster putting red pepper on a hot stove. Another teacher was attacked with a heavy inkwell (“thrown at his head by a degenerate son of an honorable townsman”) and still another was stabbed in the arm. The school on the corner of Fifth and D was the only place where “white and colored pupils were received and treated as equals.” [A history of the Petaluma schools found in the centennial edition of the A-C states it was originally all African-American and integrated later in the decade] |

|

Ed complained often Vallejo’s Old Adobe was never a fort or ever called Casa Grande – until he discovered a man named Bliss bought the place in 1859 and indeed renamed it “Casa Grande.” Oooops! |

|

“Petaluma looks toward the future, not to the past, and forthwith carted off a great deal of valuable local memorabilia to the city dumps,” Ed griped about the Chamber of Commerce. Several times he complained the city itself had carted away a 5-foot bronze statue of a nude Greek goddess which once was perched atop the fountain at the corner of Washington and Main |

|

Petaluma made Santa Rosa furious by setting steamboat schedules so “up-country” travelers had to stay overnight at a local hotel |

|

Someone gave Ed the last surviving copies of very short-lived newspaper called “The Weekly Amateur,” put out by Petaluma youths around 1887. While it mostly reflected their interests in baseball, doings of the volunteer fire department and entertainment, there was also this vignette: “Some Petaluma youths do not seem to appreciate our gas lamps by the way they are perforating them with sling shot missiles. Any way, what a great satisfaction it is to a boy to see a light of glass crackle to pieces by his proud marksmanship. If the proprietor or cop gives chase, he is all the more delighted” |

|

Petaluma inventor Jacob Price Jr. might have been considered the Edison of farm equipment c. 1860-1880, designing steam tractors, seed sowing machines and the famous “Petaluma Press,” which could bale 3,600 pounds of hay an hour |

|

His mention of Luther Burbank brought a response from Edgar Waite, the reporter whose controversial interview in 1926 revealed that the much-respected Burbank considered himself an “infidel” and that Christianity had “garbled” Jesus’s teachings. An uproar followed, but it’s never been clear if this caused him stress that led to his heart attack a couple of months later, followed by his death at 77 years. Waite – who personally knew Burbank from his time as a Press Democrat reporter – wrote to Mannion, “I went up to see my friend again, and to make sure that he felt no regrets. He didn’t. On the contrary, he expressed himself as happy that his views had been spread on the record, and bemoaned only the mountain of correspondence that had descended upon him” |

|

| Chris and Ed Mannion, undated photo. Courtesy Petaluma Museum |