Had Martin Tarwater behaved himself, he would have died peacefully at home near Mark West Creek and been quickly forgotten. Instead, he did something so crazy that he was immortalized in one of the best stories written by Jack London.

London spent a few weeks with Tarwater during the 1897 Yukon Gold Rush. Martin was 66 years old at the time and had no experience with prospecting or, for that matter, surviving in extreme weather conditions, having lived his entire adult life in the placid clime that is Sonoma county. He lacked backcountry gear and didn’t arrive in Alaska with much money, in stark contrast to the others who were pouring off the boats equipped with a ton of outfitting and grubstakes to pay for whatever else they would need. What Martin Tarwater had instead was a boundless cheery attitude and indefatigable certainty that in spite of everything he would triumph in the end. And because of that, Jack London made him a hero.

On a genealogy web page one contributor sniped, “It is hoped no one will find that story (included in one of his books, the title I have forgotten at the moment), because everything written about Martin Tarwater is complete fiction.” The story is “Like Argus of the Ancient Times” and is so named for Martin’s love of singing even if he didn’t always remember the correct words to the song. That title was part of his scrambled substitution lyrics for the Unitarian version of the Doxology hymn (“From all that dwell below the skies…”).

As for everything London wrote about him being “complete fiction,” I don’t think that’s at all true, although the Tarwater character in the story is instead named John and came from Michigan, not Missouri. But mostly everything in the story up to the ending tracks very well with what appeared about Martin in local newspapers and in writings of his Klondike compatriots. No spoilers here, but you’ll enjoy the rest of this article more if you take a moment and let Jack London introduce him to you.

“Mart” Tarwater – as apparently everyone called him – came here in 1853, which is to say he was here before Santa Rosa was here. He and wife Sarah had several hundred acres near the headwaters of Mark West Creek and like most of his neighbors, proceeded from logging redwoods to ranching to grapes. He had the largest sheep ranch in the area and nine children, not all of whom lived to adulthood. His eldest son died in his arms after a farming accident. There is still a Tarwater Road off St. Helena Road and there was a Tarwater school district with a one-room schoolhouse which served for dances and other get-togethers. Oddly, they named their micro-community “America.”

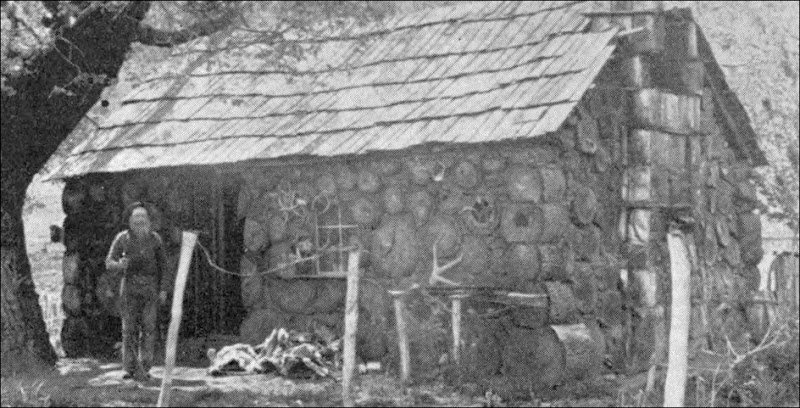

In a Believe-it-or-Not! twist, Charmian London met the unforgettable Mr. Tarwater first, while her future husband was still playing oyster pirate. In volume two of her biography of Jack she wrote of accompanying her aunt, Ninetta Eames, as she trekked about the North Bay researching an article. Charmian wrote she “made a pilgrimage to his mountain cabin and sketched that abode and himself for an illustration,” but that’s not entirely true; while the article had drawings (by Grace Hudson, no less) it was a photograph that appeared in the August, 1892 Overland Monthly captioned, “A Shepherd’s Arcady.” Thus if she’s right about meeting Martin, that’s him in this picture:1

Jack’s story begins in the summer of 1897, as does the provable history. “Grandfather Tarwater, after remaining properly subdued and crushed for a quiet decade, had broken out again. This time it was the Klondike fever,” wrote London. “The multitudinous family had sat upon him, but had had a hard time doing it. When all else had failed to shake his resolution, they had applied lawyers to him, with the threat of getting out guardianship papers and of confining him in the state asylum for the insane.”

The fictional Tarwater sneaks out of the house the next morning and took the horses and wagon to Santa Rosa, where he sold them and other items, raising $42.50 before taking the train to San Francisco. “A dozen days later, carrying a half-empty canvas sack of blankets and old clothes, he landed on the beach of Dyea in the thick of the great Klondike Rush. The beach was screaming bedlam.”

In truth, we know nothing about Martin’s departure – which suggests Jack London had it mostly right. When local residents left for Alaska (or were even rumored to be possibly thinking about going, maybe) there was an item about it in one of the Santa Rosa newspapers. For Martin there was not even the customary single-line mention of his going to San Francisco, which strongly implies the family kept it quiet.

Among Mart’s fellow travelers over the next week would be Fred Thompson of Santa Rosa. Fred is worth special mention because he left a diary (which scholars often cite) and wrote several letters to the Republican newspaper (which most scholars don’t seem to know about). Fred was a court reporter and brother of Rolfe L. Thompson, well-known to readers of this journal for being the lawyer who led attempts at reform efforts in the years after the Great Earthquake.

Through Thompson’s first letter, dated August 1, we meet the other four members of his party: Someone else from Santa Rosa and a carpenter with some experience building boats, plus “J. H. Shepard, 1068 East 16th street Oakland, Cal., who is an attorney and quite a well to do man and an old prospector and miner–a personal friend of Judge Crawford who can tell you all about him; Jack London of same address as Mr. Shepard and a brother-in-law. Mr. Shepard is backing Mr. London, who is a sailor and marine engineer.” It’s amusing that 21 year-old Jack London was trying to pass himself off as a “marine engineer,” but even more howling was James Shepard claiming to be a sourdough miner and “well to do.” Shepard, the subject of the previous item, was a ne’er-do-well military pension lawyer whose wife mortgaged the home in her name to fund his misadventure.

The first glimpse of Mart on his odyssey comes from Santa Rosa blacksmith John Poat, who wrote on Aug. 12 that he and another Santa Rosa fellow, Clarence Temple, were on the same boat bound for Alaska as “Old Man” Tarwater. As it turned out, our local blacksmith found it too much to endure and was back in town by the end of the month. He gave an interview to the Republican and told them, “I left Tarwater and Temple in Juneau. The former, when saying good-by to me the day I left, said he was going to do his best to get in with a party and work his way over one of the passes.”

The narrative resumed with an Aug. 24 letter from Clarence Temple. He wrote to the Republican that Mart had fallen in with a party and gone to Skagway, expecting to go over the pass at once. The “old man” was in luck for he was not well equipped with cash and could not have gone over the pass alone, the paper summarized.

All of the Santa Rosa adventurers told the paper of the daunting conditions. “At Juneau it is believed that hundreds will perish on the way to Dawson,” wrote Poat. “Those who have taken tents will find them useless when winter sets in. They say at Juneau that the only way one can pass an Alaskan winter is to build log huts, make them almost air tight, and then keep a roaring fire going all the time.” Another correspondent told the paper he had just left Dawson City – the destination camp everyone looked to as a refuge – on Aug. 26 because stores and restaurants were already closed for the winter because there was no food to sell.

The surprise correspondent was James Shepard, whose letter appeared in the Republican Sept. 27. By then he was sleeping in his own bed back in Oakland, having given up five days into the trek (he lied and claimed he made it all the way to eleven). Shepard – who supposedly had a mild heart attack even before leaving the Bay Area – wrote that he was only doing cooking chores while the other four members of the party were lugging their collective 6,000 pounds of supplies up the mountain, from 4 in the morning until around 9 at night.

Before continuing our story, it may be helpful to review Klondike 101: Tarwater, London, and the rest of our pals were on the Chilkoot Trail, later dubbed “the meanest 32 miles in history” and remembered for those photographs of the ant-like procession of men crawling up the mountainside. As the goldfields were actually in Canada, “stampeders” had to pay custom duties on their supplies at a Mountie station located at the summit. The Canadian government also required each man entering the Territory to bring along enough food for an entire year, which alone weighed half a ton. Add in camping and mining supplies and the need to combine resources with others was essential to keep the weight down.

Climbing the Chilkoot was easiest in winter when the trail was packed snow, as supplies could be pulled by sled; Jack London and the others were on it at the peak of Indian Summer when temperatures were close to 100 degrees, which meant backpacking up a craggy slope in multiple trips. Shepard wrote that when he left, their company was making 1¼ miles a day – and that was before the trail got really steep. As they were about to start the climb, London wrote to a friend how this relay would work:2

I expect to carry 100 lbs. to the load on good trail & on the worst, 75 lbs. That is, for every mile to the Lakes, I will have to travel from 20-30 miles. I have 1000 lbs. in my outfit. I have to divide it into from 10 to fifteen loads according to the trail. I take a load a mile & come back empty that makes two miles. 10 loads means 19 miles, for I do not have to come back after the 11th. load for there is none. If I have 15 loads it means 29 miles. |

The day after James Shepard turned back, Thompson entered this in his diary: “August 15. Very warm today—-did not do much. Met Tarwater of Santa Rosa–took him as a passenger, exchanging board and passage for his work.” Five or six days later, photographer Frank La Roche took the picture below, which is the only known image of Jack London in the Yukon.

|

| Left to Right: Jim Goodman, Jack London, Martin Tarwater (partially obscured by pipe), unknown man with pipe and Fred Thompson3 |

For all his faults, Shepard had contributed money and a full outfit to their party; Mart Tarwater looked like nothing but burden. He had little but the clothes on his back and was a dozen years older than the old man he was to replace. As London wrote in his short story, it wasn’t easy to convince the others to take him on. But once he was accepted in their ranks, London wrote, “Old John Tarwater became a striking figure on a trail unusually replete with striking figures. With thousands of men, each back-tripping half a ton of outfit, retracing every mile of the trail twenty times, all came to know him and to hail him as ‘Father Christmas’…On a trail where hard-working men learned for the first time what work was, no man worked harder in proportion to his strength than Old Tarwater.”

Aside from bearing his share of the burdens, London tells us Mart kept everyone’s spirits up with his enthusiastic singing: “…as he worked, ever he raised his chant with his age-falsetto voice…Weary back-trippers would rest their packs on a log or rock alongside of where he rested his, and would say: ‘Sing us that song of yourn, dad, about Forty-Nine.’ And, when he had wheezingly complied, they would arise under their loads, remark that it was real heartening, and hit the forward trail again.”

Another returnee from the Yukon told the Press Democrat of running into Mart unexpectedly:

“Suddenly while we walked along the wooded trail, a voice broke the stillness of the night. The sound of that voice seemed familiar to me. Who can it be I asked myself? As we came nearer the spot I was more convinced than ever last I knew the singer. In that strange land it was so good. Presently we came opposite the place from whence the singing came. I stood rivetted to the spot. The singer was warbling the old song “How the Miners Made Pancakes in ’49.” Leaning against a tree, his face muffled almost to hide his features, back of him the smouldering embers of his little camp fire, was a man whom I afterwards learned was none other than mv old friend. Mart Tarwater, of Mark West, the old mail carrier. Away up on the Skaguay apparently all alone old Mart was just as merry as he was when driving along the Healdsburg road in his little old mail wagon. There was no mistaking that noise. I would have known it anywhere in the world.” |

It was now September and the freezeup was a few weeks away; plans to survive the coming arctic weather had to be made before winter slammed in and made them for you. It was decided they would join with another party and construct a pair of boats to speed their journey. It was grueling work; in his story, Jack wrote, “They worked night and day. Thrice, on the night-shift, underneath in the saw-pit, Old Tarwater fainted.”

Near the end of that month, a Santa Rosa man wrote the Press Democrat: “Yesterday a party from Santa Rosa, consisting of J. E. Goodman, Fred H. Thompson, Mart Tarwater, and seven others launched a 32-foot boat in the lake and sailed gaily out of sight. They were a gay and happy looking crowd.” Over the next few days they pushed on through strong freezing winds, snowstorms and ice, not to mention shooting the boats down rapids which few attempted even in best conditions. This is the stuff of high adventure and is retold in several Jack London stories and novels.

While they were still days away from Dawson City they came across abandoned log cabins built by an old trading company. London and the Santa Rosa boys saw this as great good luck, particularly since their guide book said gold had been found in the area. The party in the other boat would continue on, with Martin Tarwater aboard. It was the last time Jack would see his elderly friend.

Mart and the others had made a terrible choice. They were unaware that Canadian authorities had just posted a notice that there were not adequate food supplies at Dawson, even with the cargo of a recent supply steamship which would be the last to make it in before spring. Any prospectors without enough personal food for themselves would have to evacuate immediately to Fort Yukon. Tarwater was among them.

A few updates appeared in the Press Democrat over the winter, among them a letter from Fred Thompson saying their group was doing well. There was also word that Mart was writing for a local paper (!) and had filed a mining claim where he was picking up $10 in gold every day off the ground. “This news is good. No one deserves to get rich any more than does Mart.” Of course, both were completely untrue.

Then came the news: Martin Tarwater had died on May 20, 1898 at Fort Yukon.

The family received a letter from a man named Orion T. Thomas, who had linked up with Mart after the Dawson evacuation. They built a cabin together but “as Mr. Tarwater had very little money,” wrote Thomas, and without the protectorship of his Santa Rosa friends, he was compelled to work, cutting wood for $5 per cord in weather 40 degrees below zero. He quickly became seriously ill. In Jack London’s story “his creaking and crackling and the nasty hacking cough” was often mentioned and Thomas wrote, “the doctor says the cause of his death was acute asthma.”

The next year Orion Thomas popped up in Santa Rosa and stopped by the Press Democrat, giving the newspaper an opportunity to write a second obituary for a favorite son.

Before he was taken sick, Mr. Thomas says Old Mart was the life of the camp. His Sonoma county friends will always remember his ready wit and his ability to launch out in verse to suit a popular air. He was the same in the frozen north, and could always be relied upon to have a stock of verse on hand concerning the Klondike, to keep all those around him in good humor. |

Thomas, who was a bugler for the Union during the Civil war, “carried a cornet with him all through his travels,” the PD reported. “He says it was very amusing to see the interest taken in his music by the Indians, who had never seen such an instrument before. Whenever he played in his cabin he could always have a large audience of Indians, male and female.”

How fitting that the last word on Martin Tarwater is from someone who shared his enthusiasm for making music. And you can bet as Orion tootled his cornet on those winter days, old Mart was howling along with the tune, even if he didn’t properly recall the right words. It was surely that odd duet which drew the Gwich’in native people over to their cabin in -40° temperatures – after all, you don’t hear unearthly sounds like that every day. No sir, you don’t.

1 Robert Tarwater had a large spread in Anderson Valley and a little item in the 1875 Sonoma Democrat mentioned Martin driving a herd of a thousand sheep up there. Robert moved there from Santa Rosa in 1857 and was likely a brother or cousin of Martin’s. I don’t particularly enjoy genealogy research, so if anyone wants to shake the Tarwater family tree, here’s Robert’s obituary.

2 Letter to Mabel Applegarth; The Letters of Jack London: 1913-1916. Volume three

3 The identification of the men was made by author Dick North in 1981 and discussed at length in his book, “Sailor on Snowshoes.” North speculated the unknown man could be Dan Goodman’s brother James or famed author and John Muir companion Samuel Hall Young, but it seems to me that it is more likely boat carpenter Merritt Sloper, who remained a member of the London party through the next year. Credit: Frank La Roche Photograph Collection, University of Washington

For many weeks past the families of Fred Thompson and J. E. Goodman of this city, and Mart Tarwater, the veteran mail carrier of the Mark West Springs district, have been looking for letters from them.

In a letter received last night from Virgil Moore, the Bulletin correspondent in Alaska, dated Lake Linderman. Sept. 29, he speaks encouragingly of the trio mentioned above. The news will be received by their friends here with pleasure.

The writer says: “Yesterday a party from Santa Rosa, consisting of J. E. Goodman, Fred H. Thompson, Mart Tarwater, and seven others launched a 32-foot boat in the lake and sailed gaily out of sight. They were a gay and happy looking crowd and had only been on the road sixty-three days.”

From this piece of news it would appear that the Santa Rosans are doing first-rate. All of the boys have good, genuine grit, and if any one can succeed they will. Their friends here will always be glad to note their success.

“I and my partner were walking slowly along the Skaguay trail one evening many weeks ago. The shades of night were falling fast. Pretty soon it got almost dark. We were making for a certain point that night. We were feeling pretty tired. My partner urged me to hurry along before the darkness got too dense.

“Suddenly while we walked along the wooded trail, a voice broke the stillness of the night. The sound of that voice seemed familiar to me. Who can it be I asked myself? As we came nearer the spot I was more convinced than ever last I knew the singer. In that strange land it was so good. Presently we came opposite the place from whence the singing came. I stood rivetted to the spot. The singer was warbling the old song “How the Miners Made Pancakes in ’49.” Leaning against a tree, his face muffled almost to hide his features, back of him the smouldering embers of his little camp fire, was a man whom I afterwards learned was none other than mv old friend. Mart Tarwater, of Mark West, the old mail carrier. Away up on the Skaguay apparently all alone old Mart was just as merry as he was when driving along the Healdsburg road in hie little old mail wagon. There was no mistaking that noise. I would have known it anywhere in the world.”

This interesting incident was told to a Press Democrat reporter on B street Friday morning by Neal Brieson, the former superintendent of the R. L Crooks ranch at Mark West, who left San Francisco on July 31, on the same ship carrying Hy Groshong, for Alaska, and who returned from there last week. Mr. Brieson went to Alaska to obtain ail the information he could relative to the resources of the country. He returns impressed with the idea that the country is very rich and one capable of marvelous developments. He went to Dyea and along the Skaguay [sic] trail. Friday morning he pulled from his pocket a bottle filled with rich golden nuggets from Dawson City. From what he learned while in Alaska, Mr. Brieson says, the horrors of the Chilkoot Pass have never been adequately described in the newspaper accounts. In fact he thinks it would fail the human tongue to describe them. He heard of Clarence Temple, Fred Thompson and Jim Goodman but did not see them. Mr. Brieson came back from Dyea with three men who were from Dawson City. These men had been on the Yukon for three years and were going home for winter as they said thev would not stay on their claims for $l0,000 during the winter for they feared a scarcity of food. Brieson says many of those now in Alaska are wishing that they had waited until spring before going. They complain very bitterly of the fairylike visions of gold told by those who came out from the Yukon when the excitement first commenced. Mr. Brieson had an exceeding interesting time in Alaska and gained lots of information. His many friends here are glad to see him again.

Everybody remembers the veteran mail carrier Mart Tarwater, the former driver of the mail cart from here to Mark West Springs, and who in conjunction with a few others got the gold craze last fall and went to Klondyke.

For several months nothing has been heard of Mart in any way and lots of the veteran miner’s friends have wondered what had become of him.

Thursday it was learned that Mr. Tarwater’a family had heard indirectly from him through a Calistoga man who returned from the Stewart river district a few days ago.

The returned miner brought the news that he had seen old Mart on Stewart river just before he left; that he was well and that he was making things “stick.” The man said that Mr. Tarwater had a claim on Stewart river and in taking out ten dollars’ worth of tbe shining metal per diem “right off the surface.”

This news is good. No one deserves to get rich any more than does Mart.

After a long silence a letter was received here Tuesday by Deputy County Clerk R. L. Thompson from his brother Fred, who in company with Jim Goodman of this city and others left last fall for Dawson City.

The letter bears date: “Stewart City, on Henderson creek, N. W. T., October 10.” [EDITORIAL NOTE: This date is clearly wrong, as Jack London and others had formed the camp. This letter was most likely written in December or January. According to Charmian’s biography, they were in Dawson from about Oct. 20 to Dec. 3. -je] The writer says that his party are well and are pleased with the country. They had a terrible time crossing the Chilkoot Pass.

The Thompson party claim the distinction of having come across a spot on Henderson creek on which was an old unoccupied cabin and having named the place Stewart City.

Four days after their arrival at Stewart City they prospected on Henderson creek, and finding good color, located claims. Fred Thompson went on to Dawson City and filed on claims for each member of the party. He remained in the vicinity of Dawson City tor seven weeks and located other claims, one being on Sulphur creek. While there he says he was offered $4,000 for one of his claims on the Henderson creek, but refused to sell. At Dawson City he met the former poet-journalist of Santa Rosa, Virgil Moore, and had a very pleasant talk with him.

Fourteen claims are owned by Thompson’s party. They are now working the claims on Henderson creek. The writer’s description of the way in which they made their boats at Lake Linderman and shot the White Horse rapids is very graphic.

The boys seem confident of success and all their Santa Rosa friends sincerely trust that their hopes will be realized to tbs fullest extent. The receiving of the the letter here wae a great pleasure to the relatives of both Messrs. Thompson and Goodman.

News received from Yukon state that Mart Tarwater, tbe former mail carrier from Santa Rose to Mark West Springs, and who went in the rush to the golden north early last fall, ia now writing for newspapers started in that region.

News has been received of the death of M. Tarwater in Alaska, sent, it is stated, by the minister who read the burial service at his funeral, says the Press-Democrat. When last heard from Mr. Tarwater was sick in the hospital near Dawson City. Mr. Tarwater, it will be remembered, was the veteran mail carrier to Mark West Springs and Altruria, and for events which have transpired in California and Sonoma county in early days, he was an encyclopedia. Few men were better known, and at every fireside in Sonoma county, he was a welcome guest.

Last Saturday morning the Press Democrat published a report of the death, in Alaska, of Martin W. Tarwater, a pioneer of Sonoma county and formerly mail carrier between this city and America postoffice. No confirmation of the report could be secured by this paper at that time.

Nevertheless, Mrs. Tarwater then had in her possession a letter received last Thursday from Orion T. Thomas, formerly of Los Angeles, containing news of the death of Mr. Tarwater on May 20. Mr. Thomas was a constant attendant of the deceased during the last days of his life. Mrs. Tarwater, who resides at America still has hopes that her husband is alive, despite the conclusiveness of Thomas’ pathetic letter, which is herewith printed:

“Fort Yukon, Alaska, May 22, ’98.

“Mrs. M. W. Tarwater— Dear Madam; It is my sad duty to inform you of the death of your husband, which occurred Friday morning, May 20, 1898, at 3 o’clock. Mr. Tarwater had been sick nearly two months, and the doctor says the cause of his death was acute asthma, although he also suffered from liver trouble.

“The burial took place Friday evening from the Episcopal mission, Rev. J. W. Hawksley officiating. The remains were interred in the Fort Yukon graveyard. I had a headboard painted with his name, age, time of death and native state (Missouri) placed at the head of his grave.

“I first met Mr. Tarwater last November on my arrival here from Dawson City; we worked together on a large cabin, and on its completion we bunked together, but as Mr. Tarwater wrote you a long letter, sometime in December, I think he undoubtedly told you of the hard trip into this country, and working in the woods with the thermometer forty degrees and more below zero.

“Early in March, Mr. Tarwater and I bought a stone, axes, etc., and went to an island about three miles from here, to cut wood for the North American Trading and Transportation Company, for which we were to get $5 per cord. We had to wade in snow about three feet deep and cut brush to fall the trees on, to keep them from being buried in the snow, and cutting, splitting and piling wood under such circumstances was hard and necessarily slow work, especially for a man as old as Mr. Tarwater—-fifteen years older than myself. We had been working about three weeks when your husband took sick aud we had to leave the island and come back to the cabin at the Fort, I pulling him part the distance on a sled.

“When Mr. Tarwater took sick he gave me your address and requested me ‘if anything should happen to write to you and take charge of his effects.’

“Mr. Tarwater seemed to improve after he got back here and we thought he would he able to start for home on the first boat down the river; I went to Lieutenant Richardson and he promised me he would provide him transportation home, as Mr. Tarwater had very little money; both of us together only cut twenty-six cords of wood.

“We all had hopes, and Mr. Tarwater was confident that he would be well enough to start home on the first boat, but he suddenly grew worse and be passed away peacefully–regretting that be could not be at home where loving hands could help and soothe him in his last hours.

“I did what I could for Mr. Tarwater–cooking, washing and care–and I must say I never saw a man with more patience–I never knew him to become angry with anyone, no matter what the provocation.

“There was not much expense. I paid the doctor, gave the two men tbat made the coffin each an ax and gave the cooking utensils, etc., to the men who were in the cabin and assisted in getting ready for burial. There is a little money left, and although the men here say I more than earned it in taking care of him, I will if I ever get out of here alive and with any money, send it to you-—not charging anything for my services.

“Inclosed is a certificate from Minister Hawksley, which I asked him to give me.

“I left my home in Los Angeles the 26th day of last July, and like Mr. Tarwater and hundreds of others, found myself down here in November, where we were compelled to come in order to get provisions. I expect to leave here in a day or so for Dawson City. I will mail this letter at Circle City on the way up.

“Please accept my sympathy in this bereavement. Sincerely yours,

“Orion T. Thomas.”

Following is the certificate of burial by the Episcopal clergyman, which was enclosed in Mr. Thomas’ letter…

Yesterday a letter was received from Fred Thompson, who is at Dawson City, which contained much of interest to his family. With Mr. Thompson at Dawson City when the letter left there, were James and Dan Goodman, also of Santa Rosa. The trio were engaged in shipping logs from Stewart river with which to build a cabin for the winter. All the Santa Rosa boys, the letter stated, are well.

O. T. Thomas, who was with Mart Tarwater, the former veteran mail carrier of Mark West springs, when he closed his eyes in death in far-off Alaska, called at the Press Democrat office last night, and from him was learned much to interest the old pioneer’s friends all over the county.

Mr. Thomas and Mr. Tarwater shared a cabin together while both were chopping wood. The old man seemed to suddenly break down, Mr. Thomas said last night, and finally grew so weak that he had to give in. Very tenderly Mr. Thomas watched over him until the summons came, which ended his long and eventful career.

Before he was taken sick, Mr. Thomas says Old Mart was the life of the camp. His Sonoma county friends will always remember his ready wit and his ability to launch out in verse to suit a popular air. He was the same in the frozen north, and could always be relied upon to have a stock of verse on hand concerning the Klondike, to keep all those around him in good humor. Mr. Thomas took quite a liking to Old Mart. He bore his last illness bravely and without a murmur.

Mr. Thomas talks very interestingly of the time he spent in the north. He carried a cornet with him all through his travels. He says it was very amusng to see the interest taken in his music by the Indians, who bad never seen such an instrument before. Whenever he played in his cabin he could always have a large audience of Indians, male and female.