And so it came to pass: On election day 1912, a swath of the county declared alcohol welcome no more.

It would be more than seven years before prohibition was imposed upon the entire nation, but the unincorporated parts of the second district voted to ban sale and possession of alcohol, making it one of three areas in the Bay Area that went “dry” in 1912. At the time the second district was a north-south strip west of the Laguna, from Graton to Petaluma. About a dozen saloons and roadhouses were forced to close but the ban did not affect the incorporated towns of Petaluma or Sebastopol, which were also in the district.

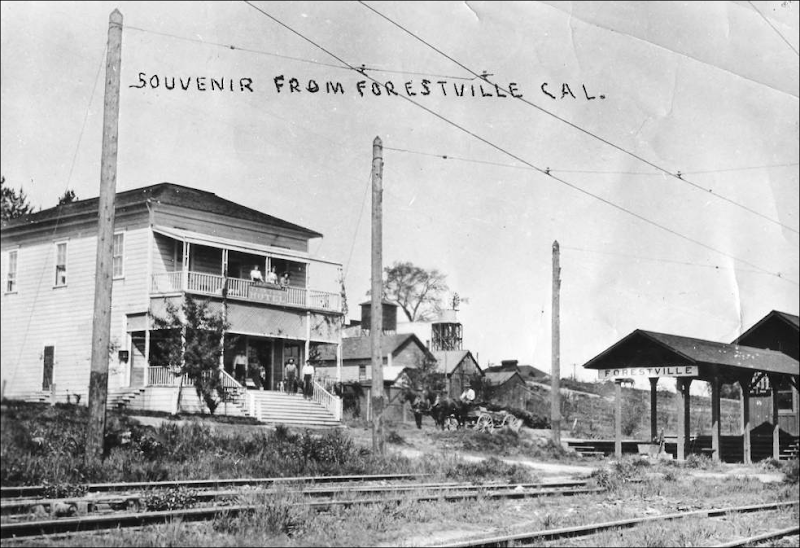

(RIGHT: Our first speakeasy? In 1913 the Sonoma County sheriff raided the Electric Hotel in Forestville for having alcohol in the “dry” district. As seen in this c. 1910 photo, the hotel was directly across from the electric railway depot. Image courtesy the Western Sonoma County Historical Society)

(RIGHT: Our first speakeasy? In 1913 the Sonoma County sheriff raided the Electric Hotel in Forestville for having alcohol in the “dry” district. As seen in this c. 1910 photo, the hotel was directly across from the electric railway depot. Image courtesy the Western Sonoma County Historical Society)

Both Santa Rosa newspapers said the vote to ban booze was expected, and not just because of moral objections against alcohol. “Residents of that district believe that prosperity will come in greater quantity with the elimination of the saloons,” the Santa Rosa Republican editorialized. “They anticipate seeing large numbers of settlers becoming their neighbors who object to living in localities where saloons are tolerated.”

This law had a ripple effect; the day after the election, the Supervisors revoked the liquor license for Jacob Kobler’s long-established saloon at Woolsey Station (about the intersection of River Road/Olivet and a stop for the train servicing the Russian River resorts). At the hearing the sheriff testified he had been called there several times because of brawls and fights, but the main charge was that he sold drinks to Indians and “half breeds” – more about this below. And that wasn’t all; someone said they witnessed “four American women get happy through the booze at Kobler’s place,” a double infraction because women were not allowed to visit a saloon, much less “get happy.” Thus the excuse to take away Mr. Kobler’s right to do business was because he failed to discriminate against minorities or women, as the law required.

All of that still might have been overlooked – the Supervisors had tabled a previous complaint against him – but what seemed to stir the Supes into action this time was testimony from two farmers griping they weren’t getting enough work out of their laborers during harvest time because they were lured away by the nearby watering hole. One complained about the “general demoralizing effect the saloon had on the prosperity of that section,” according to the Republican, and “he estimated that thousands of dollars had been lost to the community by permitting Kobler to maintain the saloon there.”

Taken together, the vote to make West County dry and the revoking of Kobler’s license had the same reason – the notion that the saloons and roadhouses were causing financial harm. In West County it was said they were discouraging property sales; Kobler was supposedly reducing productivity. Money, not morality, closed the bars. That was not unusual. In the following years there would be ongoing skirmishes in the Sonoma county prohibition wars, and liquor laws were often really an excuse for someone to make a better profit or provide a reason to restrict something else, such as gambling, prostitution or dancing to popular music.

This conflict began in earnest soon after the 1906 earthquake and while I’ve written about those events piecemeal, going forward it will be good to review the overall backstory and some of the main players in it. To wit:

The first confrontation came when the 1907 Santa Rosa City Council debated allowing bars to stay open until ten at night. The forces of temperance wanted to keep the 8PM closing time plus adding complete shutdown on Sundays. The council meetings were packed; three churches adjourned Wednesday night prayer meetings so the faithful could attend and “watch as well as pray.” From the pastors the Council heard a highly emotional plea. A petition was presented “…on behalf of the 2,000 boys and girls of this city, who are now exposed to the vile language often heard in front of the saloons” and it was widely presumed the churches were creating a blacklist of businesses refusing to sign. The saloons won that round and in the end it turned out to be much ado about not much – only 134 signed the petition.

With 1908 shaping up to be a major election year, there was a showdown between business-as-usual types and the “Municipal League,” a loose coalition of prohibitionists, anti-corruption progressives, and voters angered over Santa Rosa’s legalization of Nevada-style prostitution. Chamber of Commerce president and Press Democrat editor Ernest Finley called them agitators stirring up “hard feelings” in town with a secret agenda to turn Santa Rosa dry. Leading the reformers was Rolfe L. Thompson, an attorney and progressive politician who charged a tight group of “bosses” were controlling the town.

To show church-going voters the good ol’ boys were willing to crack down on booze, they completely banned it for Indians. A county ordinance passed early that year made it a misdemeanor to “give liquor to a person who is even one-fourth of Indian blood, or to any person of Indian descent who lives or associates with persons of one-fourth or more Indian blood.” And although that wording seemed so broad as to be unenforceable, Santa Rosa newspapers were regularly peppered in years following with little items about some guy serving sixty days or paying a steep fine for selling a bottle to a Native American. This was the law that closed Jacob Kobler’s place.

Finley and the status quo won those local elections in 1908, but faced a greater threat three years later when the state passed the Local Option Law (AKA “The Wyllie Act”), which allowed communities “to regulate or prohibit retail liquor business,” and that usually boiled down to an up-or-down vote on whether to go “dry.” Fighting hard to defeat it in the state senate was Louis Juilliard (D-Santa Rosa) who tried to amend the bill so that votes would be only cast by entire counties, which would have probably blocked prohibition passing anywhere in the state. It was the local option law that allowed the second district to vote itself dry, as explained above.

Also in 1911 women in California won the right to vote, in spite of a well-funded opposition campaign by the liquor industry, which feared suffrage would inevitably lead to passage of prohibition laws. This time Finley and the Press Democrat championed women’s rights and allied with Rolfe L. Thompson along with other suffragists, most whom strongly supported prohibition.

Besides the second district in Sonoma county, about twenty California towns had ballot items in 1912 to decide if their community would go dry. Cloverdale held a series of spirited public meetings; at the weekend rally before the vote, Andrea Sbarboro, the founder of the Italian Swiss Colony in Asti, made a rare public appearance to speak against the proposal. In the end the township of Cloverdale voted for leaders who promised to clean up the saloons – particularly gambling and serving liquor to minors – but rejected outright prohibition by an almost 2:1 majority. Overall, about half of the towns voting on alcohol went dry; in the Bay Area, only Los Gatos and Mountain View closed their saloons. Women did not vote as an anti-alcohol bloc after all; “FEMALE OF SPECIES AS THIRSTY AS THE MALE,” quipped the Santa Rosa Republican headline.

On next Tuesday, June 11, the voters of the Second Supervisorial [sic] district, which is represented by Supervisor Lyman Green, will have an opportunity to declare their preference for a “wet” or “dry” territory. Outside of the two incorporated towns of the district, Petaluma and Sebastopol, all the voters of the district will have an opportunity to express themselves.

There are eleven precincts whose residents will vote on the proposed abolition of the liquor traffic in that section. These include Bloomfield, Blucher, Hessel, Pleasant Hill, Molino, Graton, Forestville, Marin, Wilson, Two Rock and Magnolia. In the district there are fourteen other precincts, eleven being in Petaluma and three in Sebastopol. As these are incorporated towns, their inhabitants cannot vote on the matter.

For some time past both sides of the controversy have been more than active in behalf of their beliefs. Rev. A. C. Bane, the well known Anti-saloon League worker, has been spending some time in the district making addresses against the saloon and telling the people of the importance of abolishing it in their midst. For the other side Secretary F. T. Stoll of the Grape Growers’ Association of California and Senator A. S. Ruth of Olympia, Washington, are making addresses all over the territory. Assisting Rev. Bane in his efforts to defeat the saloon are T. H. Lawson of Oakland, W. P. Rankin of Sebastopol, A. L. Paul of Petaluma and others.

Mr. Stoll’s addresses are on the subject, “The Effect of Local Option on Sonoma County’s Wine Industry.” Those of Senator Ruth are “Prohibition a Failure.” These gentlemen have covered the territory completely and have spoken a number of times in each precinct.

Rev. Bane has been engaged in the work of fighting the saloons for many years past, and is the leader of the opposition to the thirst emporiums. He is a talented and forceful speaker, and his services have been in demand all over the state in the effort to bring prohibition. Mr. Stoll is likewise a bright speaker, and he has done much work to prevent various sections of the state going dry where local option elections have been held in the past.

The prediction is freely made by those who claim to be in close touch with the situation that the district will go into the prohibition column when the votes have been counted.

The local option election in Supervisor Lyman Green’s district yesterday resulted in a big victory for the “drys.” The “dry” majority was 418. Only one precinct in the district went “wet,” and that was Graton by seventeen. Hessel precinct was a tie vote, 68 to 68.

Before election day it was pretty generally conceded that the supervisoral district would vote for “no license,” and by a safe majority. Within the next ninety days the will of the people as expressed at the polls yesterday will become effective, and the dozen or so bars in the territory in the district outside of the incorporated towns of Sebastopol and Petaluma, including several roadhouses, will go out of business. The vote by precincts was as follows:

| Precinct | Dry | Wet |

| Wilson | 137 | 50 |

| Two Rock | 113 | 48 |

| Marin | 73 | 59 |

| Magnolia | 173 | 82 |

| Pleasant Hill | 83 | 33 |

| Blucher | 109 | 99 |

| Molino | 164 | 110 |

| Bloomfield | 120 | 96 |

| Hessel | 68 | 68 |

| Graton | 119 | 136 |

| Forestville | 155 | 115 |

| Totals | 1314 | 896 |

The result of the local option election in the Second Supervisorial district Tuesday is not surprising to those who know of conditions existing there. It was generally believed that the majority of the district would oppose licensing of saloons. The grape and hop industries play but a minor part in the production of the wealth of that part of the county. The agricultural pursuits of the district run more to apples and berries.

Residents of that district believe that prosperity will come in greater quantity with the elimination of the saloons. They anticipate seeing large numbers of settlers becoming their neighbors who object to living in localities where saloons are tolerated. As a result of Tuesday’s election saloons in the incorporated cities of Sebastopol and Petaluma are the only ones of the district that can continue in business.

The Petaluma Independent has the following to say in regard to the wet and dry question:

“Reliable information has reached this office to the effect that the local option forces in Sonoma county, encouraged by their success in the Second district, are prepared to invoke the initiative to bring about a ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ election throughout the county. Headquarters are to be opened at once in Santa Rosa and a vigorous campaign will be waged by the ‘drys.’ We are not at liberty to disclose at present the source of our information, but we have it from one that is absolutely reliable.

“Indications are that the campaign will be bitterly fought on both sides and neither will lack for funds to carry the fight.

“The elections in the First and Second districts are regarded as merely preliminary skirmishes, designed to test out the strength of the contestants in their respective strongholds. As the ‘wets’ polled a majority of only 254 in the First district against a ‘dry’ majority of 418 in the Second, the advantage is, for the time at least, with the latter.”

The Good Government League of Healdsburg is preparing to have a new ordinance introduced there regulating saloon business and increasing the license to $400 per annum.

Rev. E. B. Ware has prepared the draft of the new ordinance which he has done at the instance of the Good Government League and as its representative. Unless the Board of Trustees shall agree to the adoption of the same, the League proposes to have it adopted through the initiative and will press the matter to an issue at once.

The new ordinance is drafted along similar lines to that at Sebastopol. There will be no frosted windows if it is made effective and all the saloons will have plain glass fronts, that passers-by may see who is drinking at the bar; card playing will be eliminated and other features are incorporated in the new law.

Sheriff J. K. Smith and Deputy Sheriff McIntosh made a raid Thursday on several saloons being conducted in the dry territory in Sonoma county. One arrest was made and a large amount of beer and liquors were secured. Another arrest will follow later.

Hugh McConnell of the Electric Hotel at Forestville was arrested and charged with selling beer, although he claimed it was near beer. Between twenty-five and thirty bottles of whiskey were also found in the search of the premises, which is a violation of the Wylie [sic] Local Option law in itself without any attempt being made to sell it.

The saloon of C. L. Curtis at Graton was also searched, and while the proprietor was absent two cases of beer were found and several cases of near beer. Mr. Curtis will have the opportunity to explain in court his side of the case later.

McConnell was brought to Sebastopol where he put up $100 cash bail to appear when the case was called. He owns the property, and only a light bail was enacted.