Today it’s that hulking building off highway 12, best known for its parking lot swap meets and farmer’s markets. There used to be frequent public events held within its fading blue walls, but now not so much – I doubt most people now living in Santa Rosa have ever been inside. But go back seventy years and you’ll find the place was a hot topic in the town, sparking more anger and controversy than probably any other local issue in the years immediately after WWII.

And it all began with such good, good intentions.

To explain what happened we have to reach back to the early 1920s, when Santa Rosa accepted the “Pinehurst Addition” to the city. The developer was Christopher Columbus “C. C.” Donovan, who named the single street through the block Denton Way after the maiden name of his wife. (If you live in the Ridgway Historic District, a much shorter version of this story appeared in the summer, 2018 newsletter.)

The street was unusually wide and without true curbs, allowing cars to park overlapping the sidewalks. Also unusual was that Chris Donovan wanted an arch over the Mendocino Av. entrance and the “Way” in the name probably was a tipoff the broad street would be a gateway to something else.

At or around the same time in 1922, the Catholic diocese purchased the middle of the next block, immediately to the west. There the church intended to build its large grade school. As the Donovans were ardent Catholics, it seems most likely the two deals were coordinated – that Donovan’s new residential street was intended to be a grand boulevard welcoming everyone to the massive three-story Spanish-style school at the other end.

At or around the same time in 1922, the Catholic diocese purchased the middle of the next block, immediately to the west. There the church intended to build its large grade school. As the Donovans were ardent Catholics, it seems most likely the two deals were coordinated – that Donovan’s new residential street was intended to be a grand boulevard welcoming everyone to the massive three-story Spanish-style school at the other end.

Placing a big building like that in a dense residential neighborhood may seem like an idiotic plan, but it was actually a smart idea at the time. There were then only about a handful of houses surrounding the school site. The “pro” at the Santa Rosa Golf Club, Donald “Mac” MacPherson, lived on Morgan street and was using the mostly vacant block as his private driving range.

At the same time there was considerable buzz that this area of Santa Rosa was about to become the academic hub of all Northern California. In 1921 a deal was made to buy the current Santa Rosa High School site. It was predicted that the property directly to its west would become a two-year junior college, and land to the north – now the SRJC campus – would eventually become a branch of the University of California’s agricultural department. With the addition of this grade school, a youth could spend at least fourteen years in school within less than a square mile.

“It will make of Santa Rosa the educational center for the entire seven North of Bay counties, including Sonoma, Napa, Marin, Mendocino, Lake, Humboldt and Del Norte, bringing here hundreds of students who can conveniently reach this city in two or three hours’ travel, and making it possible for them to return home over the week-ends,” gushed the Press Democrat.

Nothing appeared in the newspapers during the 1920s about this proposed location for the Catholic grade school; we only know about the plan because it was described when the church sold the property in 1931. The diocese was probably motivated by the need for money during the Great Depression, as well as the city finally improving the section of 9th street between Morgan and A streets – it was previously described as being no better than an alley. The school could now be built at its present location, behind St. Rose church on the grounds of the Ursuline Convent. (It was closed as a school in 1983 because of seismic concerns, but has since been restored for office use; the campanario at the top was recreated using foam.)

And so that property sat idle for another fifteen years, undisturbed except for the thwacking of Mac MacPherson’s balls.

Fast forward now to the early months of 1945. The war in Europe was racing to its close and Americans began considering how to memorialize their dead. There was little or no interest in heroic monuments and statues of generals; in magazine articles and newspaper editorials, popular authors and notables pushed for “living memorials” instead. The notion got a big boost with the preservation of 5,000 acres of old-growth redwoods in Del Norte county; the National Tribute Grove was a cause for nationwide celebration. The American Commission for Living War Memorials was formed to promote the idea and California had its own state commission.

But what would a “living memorial” be in an average American town? A public park? A community center? An occasional-use auditorium? Or would it be American Legion halls exclusive to veterans, which the legionnaires here had been demanding since 1944? Who would get to make that decision – the vets or elected officials? And not least of it, who among the living was going to pay for whatever form that memorial would take?

There were public meetings and debates on this throughout 1945, most contentiously at a September Board of Supervisors meeting where about a hundred veterans filled the meeting room. From remarks appearing in the Press Democrat the next day it appears that the vets were about evenly divided as to whether a memorial building should be for the community or themselves alone. But what was said at the meeting united them in anger.

“You fellows are mostly veterans of World War I, and I think we should perhaps wait for the young boys of this war to get back and see what they want,” began Supervisor E. J. “Nin” Guidotti/Fifth District (Guerneville). He continued:

| Now I’m not a veteran – no more than many of the rest of you would have been if Uncle Sam hadn’t reached out and grabbed you by the collar. Yet I challenge anybody to deny my patriotism, whether I went to war or stayed home. When I hear veterans ask for things I rather wonder – is the only reason they went to war to come back and get something for themselves? …If the veterans only want buildings restricted to their use, I’m going to question their sincerity. Only recently a group of Santa Rosa legionnaires appeared before our board and their spokesmen, in effect, admitted that they only wanted a building for themselves and to [hell] with anybody else. |

“Many of them went home mad as hornets,” observed the PD, which reported the vets didn’t like being “bawled out” by a Supervisor who didn’t serve his country’s military. That evening the Santa Rosa VFW post held an “indignation meeting” and the American Legion issued a resolution denouncing Guidotti’s “un-American” conduct and “nefarious manner.”

Ding! End of round one.

Impolitic as Guidotti’s remarks were, he may have broken the legionnaire/VFW stranglehold over the debate, and committees made up of vets as well as civic leaders were formed in most towns to discuss what they wanted. It would take years before most towns, including Santa Rosa, made a decision.

Neither was there a clear idea how everything would be paid for, with estimated costs north of two million. In 1945 Santa Rosa voters turned down a $100,000 bond. A change in state law allowed counties to temporarily increase property taxes for war memorials, so the Board of Supervisors approved a bump of 25¢ per $100 assessed value – then lowered it to 20¢ after much public squawk. But in truth, that tax would have had to double in order to come close to the target; at best, it would bring in about $1.2 million before it expired in 1951.

And this brings us to round two: The Board of Supervisors meeting of March 8, 1946.

Chairman of the Board was Lloyd Cullen/Santa Rosa and the agenda included a proposal to allocate war memorial funds to each supervisorial district per its assessed valuation. That meant the biggest towns – particularly Santa Rosa and Petaluma – would get a huge pot of money while West County (which then did not include Sebastopol) would be screwed, despite being slated for three war memorials: Guerneville, Occidental, and Monte Rio.

George Kennedy – whose district included Petaluma and Sebastopol – made a motion to vote on the proposal.

“Why do that?” piped up Nin Guidotti. “You’re in a position – you and Mr. Cullen – where you have to vote for it.” Guidotti suggested it was premature to “tie ourselves” to the allocation scheme. Kennedy still made his motion for a vote, but there was no second.

The PD reported Cullen leapt to his feet. “I’m not going to be kidded out of this motion. This veterans’ matter has been kicked around long enough.” Another supervisor suggested putting it off until the next meeting.

“Let’s find out if the veterans want a memorial building or a meeting hall – it looks like that’s what they want,” added Guidotti.

“I won’t be kicked around like this!” said Cullen.

Cullen announced he was going to step aside temporarily as chairman to second the motion himself. Guidotti snapped back that he couldn’t change parliamentary rules like that, and he was just trying to put the rest of the Board on the spot. Cullen shot back that he was “going to get a written opinion” on whether he could step down.

A Supe complained, “I’m going home – I don’t feel like arguing.” A motion was made to postpone action until a later meeting, everyone voting for it except Cullen.

“It’s your steam-rolling tactics that’s stopping this,” Cullen shouted at Guidotti, according to the PD.

“I don’t want to see the veterans hog-tied…we should raise the money before we spend it,” Guidotti shouted back. “If the taxpayers of the county aren’t more favorable toward a war memorial than the people of Santa Rosa were, then we’ll probably never get one.”

Alas, the Press Democrat reporter could not write fast enough to record the whole exchange, but noted Guidotti confronted Cullen with such gems as, “That’s the kind of a dirty rat your are,” “dirty underhanded sneak,” and “yellow-bellied [bastard].”

This brought on the challenge from the Board chairman. Leaping to his feet again, Cullen pulled off his horn-rimmed glasses, threw them on the table and tore off his coat and vest, saying, “All right, if you want to fight, let’s fight it out right now.”

The other supes called for them to “quiet down” as Cullen stormed towards Guidotti, who lit a cigarette with “hands trembling” and refused to stand up. “Hell, Lloyd, I don’t want to fight,” he said. Cullen got dressed again and sat down. The Board rushed through the rest of the agenda and adjourned.

Ding!

A few weeks later, Santa Rosa announced the planned location for its war memorial. Remember the Catholic school site? That was it.

Besides being close to the High School fields and stadium which would be useful for hosting conventions, the chairman of the war memorial committee said it provided adequate parking on uncongested streets. It was also supposed to have some kind of access from Benton street and Ridgway avenue.

Besides being close to the High School fields and stadium which would be useful for hosting conventions, the chairman of the war memorial committee said it provided adequate parking on uncongested streets. It was also supposed to have some kind of access from Benton street and Ridgway avenue.

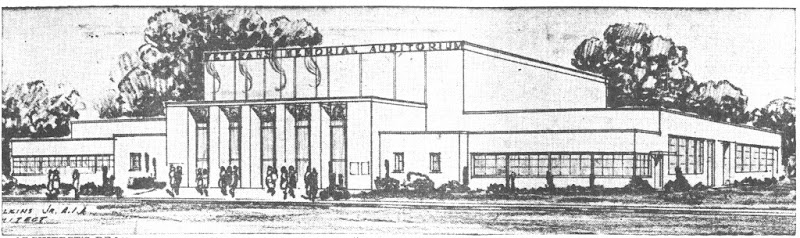

Santa Rosa’s top architect, “Cal” Caulkins (subject of the following article) drew up preliminary plans and was paid $6,036. We don’t have a picture of what he proposed (which is odd, as the Press Democrat loved to publish his drawings) but from a later description we know it was essentially the same as what was built across from the fairgrounds. It was 200 x 260 feet, had a 1,500 seat auditorium, meeting halls, lockers, a kitchen and dining hall – along with parking for just 150 cars. Apparently part of the plan was to congest the surrounding neighborhood. It was estimated to cost $580,000, which was around half of the projected tax revenue for the whole county.(UPDATE: A rendering of this building did appear in the PD in 1948 – see below.)

|

| “Cal” Caulkins plan presented to the Board of Supervisors, 1948 |

Surprisingly little happened over the next couple of years, given the passions of 1945 and 1946. The county bought property in all of the ten communities (except Healdsburg, which was just improving its memorial beach) and in most cases, paid an architect for preliminary war memorial designs. Editorials and letter writers sometimes bemoaned the expected costs, usually mentioning Santa Rosa’s $580k gorilla in the room.

And then at the start of 1949 when they were ready to break ground in Santa Rosa – everything blew up.

As it turned out, all of those land purchases were illegal – before buying the land, state law required the county Planning Commission to first inspect the properties and make recommendations.

Out tumbled a basketful of dirty secrets regarding the Santa Rosa deal. The Supervisors had paid $30,000 for that spot in the middle of a residential block without even getting an appraisal. “We bought the property on the recommendation of men who ought to know,” Supervisor Kennedy told the Press Democrat. “Somebody told me later we had paid too much for it.”

Supervisor Joseph Cox/Healdsburg: “A bunch of fellows from the Legion picked it out. They said they wanted it and we tried to give them what they wanted. I’m sick and tired of the whole deal. We’ve tried to help people out and this is what we get for it.”

They had bought the land from Wesley “Dutch” Pfister, a politically well-connected beer distributor. Pfister and a partner (who soon sold his interest to Dutch) had paid $12,750 for the parcel just year and a half before flipping it, turning him a neat 135% profit. Once that deal was made, Pfister and a couple of Santa Rosa city councilmen took a cross-country flight (quite a big deal for 1946, costing the equivalent of $3,000+ today) to see the Joe Louis vs. Billy Conn boxing match in Yankee Stadium.

Much handwringing and finger pointing followed. The chairman of Santa Rosa’s memorial committee asked the Supervisors if they could obtain a retroactive resolution of approval from Planning. Uh, no. The Planning Commission said they would be happy to consider the location – but not until the Supervisors got off the fence and wrote a policy statement declaring how the building was going to be used. There was a big difference between a meeting hall occasionally used for veteran meetings and a multipurpose community center.

A public hearing was called, and there arose the topic everyone had been avoiding to mention – namely, that was a lousy site to put an elephantine building of any kind. Yes, Denton Way was still le grande boulevard but much had changed since the Catholic school was being considered a quarter-century earlier. The designated block was now solidly residential and the memorial building would be hemmed in by backyards on both north and south sides.

Kennon Gilbert, secretary of the Planning Commission, made a suggestion – and I’m sure he thought he was being helpful. Should the Supervisors declare it was to be a public building available for rent, that income could be possibly put aside and used to “buy up the surrounding property.”

Gentle Reader, it’s time for round three at a Board of Supervisors meeting: May 31, 1949.

“I don’t think they had any damn right to open this thing up again,” remarked Supervisor Kennedy, now Board Chairman, about the public hearing. “All they were suposed to do was approve the architect’s plans and specifications. What’s Gilbert think he’s doing?” [sic]

Mr. Gilbert was not at that Board meeting, but unhappy citizens were. “All but a few” residents in the Ridgway neighborhood had signed a petition against the war memorial. It was too large, they said. It would hurt property values, they said. And if the county really were to “buy up the surrounding property,” the homeowners on Benton st. and Ridgway ave. did not have to squint too hard to read “eminent domain” between the lines.

This meeting was not so much a brawl as a pile-on – the Board was hammered with bad news about the Santa Rosa war memorial at every turn.

The veteran’s committee from the Sonoma Valley was also there and requesting the county authorize the release of funds so they could start building their war memorial. It would cost $200k, a big chunk of all tax money collected to that point.

Chairman Kennedy protested there was a “gentlemen’s agreement” with the overall county veteran’s committee that the Santa Rosa project would be built first.

“What are you going to do with Santa Rosa when you’re facing an injunction?” asked the Sonoma spokesman, apparently referring to the citizen’s petition. No action was taken on the Sonoma request.

But the Supervisors did not see the knockout punch coming. There was a surprise appearance from the chairman of the Santa Rosa city planning commission. He announced the county would have to obtain permission from the city planners before building on that site, as the block had residential zoning.

“But we bought the site before it was zoned residential,” Kennedy said.

“That doesn’t matter; you still need a use permit.”

“I didn’t know that,” confessed Kennedy.

Apropos of nothing but keeping with the depressing tone of the session, another supervisor griped that “all the trouble” over the war memorials was coming from anti-tax zealots. “They’re working underground,” he hinted darkly, without explanation.

There was (apparently) no formal resolution, but that meeting was the death of the plan to build a war memorial at the end of Denton Way. There was now a proposal to put it at the western edge of Ridgway avenue, currently the location of Cal Fire headquarters. Since a new armory was going to be built next door, the “President’s Council” – which supposedly represented half of Santa Rosa’s civic groups – argued that together the vets building and armory would form a six-acre community center. They wanted it facing the freeway and presumably with a turnoff from highway 101, “where occupants of 300,000 autos per year could view it and take away a favorable impression of Santa Rosa.” Today 100,000 vehicles pass that section per day and at modern speeds a turnoff into a parking lot would be ridiculously unsafe. Architect Caulkins was called up to report that it would add tens of thousand$ to the cost because the land would have to be graded level with the freeway.

There was also a last minute push for a non-residential site east of the Junior College, directly across from Elliott avenue. What was never explained was why the Supervisors were trying so hard to find some place in the high school/SRJC area for the war memorial.

After nearly a full year of turmoil, in September the Supervisors approved selection of the location across from fairgrounds, which now seems to be the only logical place to build such a thing. It would also be agreed that it would be a multi-use building – a convention center, as well as a bar exclusively for vets and their guests with a full liquor license. (Years later, a Press Democrat columnist remarked that the reason they gave up on the other section of town was because there would be difficulty in getting a license for a location so close to the high school.)

There was a final fight over money; the Supes accepted a lowball bid from a Petaluma contractor, raising more complaints from the veterans that “their” building was not being given due respect. And sure enough, the contractor immediately screwed up, placing the building 150 feet too far south, encroaching on fairgrounds overflow parking space that was funded by the state. The contractor, architect and assorted officials trekked to Sacramento to explain how that happened.

The Santa Rosa Veterans Memorial Building finally opened ten months late. Total cost: $630,000, including cocktail lounge.

Our obl. Believe-it-or-Not! epilogue concerns the original location at the end of Denton Way. Shortly after that depressing Supervisor’s meeting in May, 1949, the county put the property up for auction. The minimum bid was $30,000, which was their purchase price back in 1946. Three years had passed, and inflation was averaging about 11 percent a year, so surely the county would make a profit of some sort – right? Nope. There was not a single bid. The county would not be able to unload that property until 1955. The only winner in the whole story was “Dutch” Pfister, who probably was laughing about the deal with his pals during their luxe transcontinental flight to see the Louis-Conn rematch. That event was considered a dud; Dutch could have saved a fortune and watched more exciting fights if he had stayed home and attended the Board of Supervisors meetings.

|