Dear PG&E: We need to talk. I think you’re aware (dimly, maybe?) everybody hates you. It’s not just because of the deaths and the places that burned up, or even how the recent shutoffs revealed you can’t even keep a website running, much less handle the power grid. No, it’s not just neglecting to do your job properly; you’ve been behaving badly for over a century including a hot mess of corporate malfeasance. Maybe you’re hoping we’ll patch things up after your bankruptcy and jury trial over the Tubbs Fire, but not this time – we want you to get out. Let someone else run the show. Sincerely, Northern California.

Pacific Gas & Electric has a history that deserves a spot in the Hall of Infamy somewhere between the tobacco companies and the railroads. The next time you’re hanging with friends, ask each to crawl down memory lane and recall a news story about the company. Someone will surely bring up when eight were killed in the 2010 San Bruno gas explosion; auditors found PG&E had slashed the pipeline maintenance budget in order to award fat bonuses to the CEO and executives. (Afterwards, they spent tens of million$ on ads touting the company’s high commitment to safety.) An older friend might remember their mad plan to build a nuclear power plant at Bodega Head which they were determined to do even after it was discovered the San Andreas Fault ran directly through the site. There’s plenty more stories to share because the list of outrages goes on and on and on. Okay, one more: PG&E used a loophole to siphon over a billion dollars from a state fund for affordable housing. And on and on. Okay, one more: Diablo Canyon was the only nuclear power plant which generated electricity not with fuel rods, but by throwing dollars down a black hole. (And by the way, PG&E will soon sock customers with a $1.6 billion bill to pay for decommissioning the place, despite repeated promises that it was paid for in advance.) And on.

Aside from rage against dumb schemes like Bodega Head, most pushback against PG&E over the last 75 years has concerned rate increases, and came from the same pocketbook protectors who regularly manned the ramparts against taxes. But in 1952 there was a one-of-a-kind presentation given in Santa Rosa that exposed doings that the company did not want known. The Press Democrat and Argus-Courier offered more fact-filled editorials, letters and columns, and as a result the Sonoma county newspaper readers were likely the best informed people in the state that year.

The setting was a January 8 meeting at Santa Rosa’s Bellevue Grange Hall, in those years a popular place for holding meetings, monthly dances and other shindigs. Discussed that evening was PG&E’s proposed $37.6 million annual rate hike. (Inflation has gone up almost exactly 10x since then, so just add another zero on any dollar amounts discussed below.)

The speakers were Joe C. Lewis and Oliver O. Rands, both experts on hydroelectric power who knew how PG&E was making huge profits by reselling energy from the federal Central Valley system at a jaw-dropping 1,500 percent markup, buying it for only 0.4¢ per KWH and reselling it in Santa Rosa and elsewhere for about 6.5¢ per KWH. Yet the company still wanted a hefty rate hike.

Lewis was an ex-Assemblyman from Buttonwillow (best known to travelers on I-5 as, “hey look, there’s an exit for a town named Buttonwillow!”) and then the head of the “California Farm Research and Legislative Committee,” a grassroots organization representing hundreds of thousands of small farmers and farmworkers against agribusiness and PG&E/SoCal Edison. Rands was the federal Bureau of Reclamation chief overseeing the contracts providing ultra-cheap power to PG&E. As far as I can tell, this was the only time the two men appeared together to shine a spotlight on the monopoly’s practices.

PG&E’s argument(s) went something like this: Although the proposed rate hike will raise the average bill by 21 percent, that’s not a lot. Heck, some other power companies have doubled their rates in the last dozen years – thanks to our good management we’ve kept rates low. But we’re really paying a lot of taxes (more than half of all taxes collected in some counties!) and we’ve had to expand because of all the people who moved to California since the end of WWII. Our profits are way down and we might have to reduce the approx. 12% annual dividend we’ve paid our thousands of shareholders (fun fact: More women than men own stock!) this year. Also, we’re entitled to raise prices because we’re legally allowed to make a 5.8 percent profit under regulations, which makes this rate increase only fair.

Bullshit, said Lewis, Rands and the other PG&E critics. The true reason to hate PG&E in those years was because in all ways it acted more like a Fortune 500 company than a regional utility.

The company’s balance sheet was filled with hard-to-justify operating costs, starting with the president’s whopping base salary of over $107,000 – a shocking number back then, when average family income was $3,300 and a CEO typically only made 20x more than its workers (far more obscene today is that a major corporation CEO makes about 360x over the employees).

PG&E also paid over $1 million between 1949-1952 on lobbyists in Washington and Sacramento and spent lavishly to defeat ballot items it didn’t like. When Redding, which has its own municipal electric utility, held a 1949 referendum on buying energy directly from the Bureau of Reclamation, PG&E poured money into their small town politics (population 10,000) blocking the switch by spending $7 for every vote – and remember, multiply all these dollar amounts by ten.

But the most questionable item in its operation budget was “sales promotion,” which Lewis said totaled $2,100,000 in 1950. That did not include the cost of “PG&E Progress,” the chatty little newsletter sent to each customer in the same envelope as the monthly bill; much of that PR budget paid for large, expensive ads in newspapers and national magazines such as Life, Look, Time, Colliers, The Saturday Evening Post, Reader’s Digest and similar. This was certainly a major reason why it’s so hard to find any scrutiny of PG&E in the press during the 1950s – publishers are always loathe to portray major advertisers in a bad light.

The national ads didn’t tout PG&E by name; the source was a trade group that identified the ad as being sponsored by “America’s Independent Electric Light and Power Companies.” Known in the industry as the “Electric Companies Advertising Program” (ECAP) it was among the top 100 national advertisers, spending $25 million in 1950. At various times there were about a hundred ±30 companies underwriting the program and we don’t know how much of their funding came from PG&E, but you can bet it was a greater chunk than all the pee-wee members such as the Conowingo Power Company of Elkton, Maryland.

The ECAP ads from the ’50s and ’60s are often campy fun, urging consumers to embrace “modern electric living” (which usually meant buying major appliances) and feel-good “world of tomorrow” stuff (a personal favorite is found at the end of this article). But there were other ad campaigns which were anything but fluffy PR.

Another type of their print ads (ECAP also sponsored popular network radio shows) brought scrutiny by crossing the line into lobbying, particularly by complaining the companies were being taxed unfairly. Since PG&E and the other companies claimed those ads as part of their operating expenses, they sometimes were investigated or sued over doing so – and it’s only thanks to legal documents about the issue (such as this one) do we know some of what was going on behind the curtain at ECAP.

Sometimes the ads changed the name to something like, “Investor-Owned Electric Light and Power Companies” as a reminder that some of the big companies like PG&E were ready to sell stock to non-customers. While their newsletter boasted that it was California owned, almost half of PG&E’s stock in 1952 was held by sixteen East Coast corporations, according to a PD columnist.

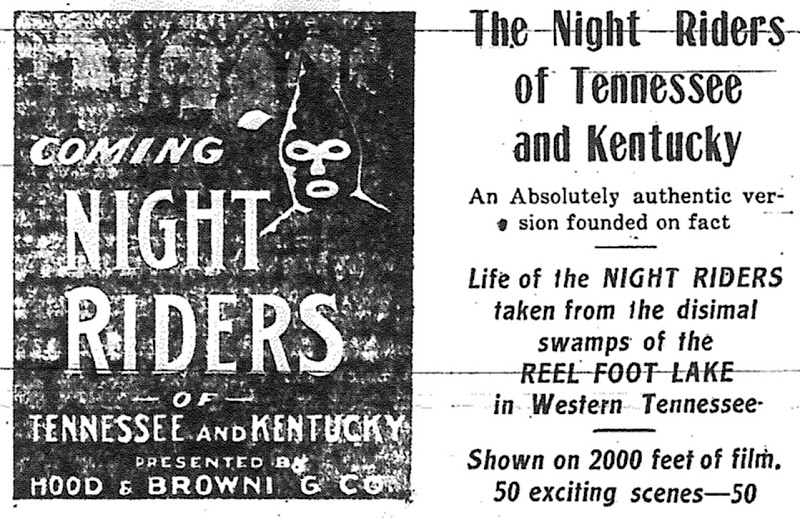

(RIGHT: 1950 ECAP ad calling public-owned utilities un-American)

(RIGHT: 1950 ECAP ad calling public-owned utilities un-American)

At the Santa Rosa meeting Mr. Rands was clearly angered by a particularly despicable class of ECAP ads that attacked municipal power utilities as “socialistic poison.” He explained that PG&E not only didn’t like the competition, but wanted to conceal that towns such as Healdsburg had much lower rates because they could buy power directly from the Bureau of Reclamation at a fraction of the cost of other places in Sonoma county.

And finally, PG&E was even covering up why they really needed to increase prices – it was in order to pay for the $62M “Super Inch” natural gas pipeline from Arizona to Milpitas. Under federal regs they had to show they had the income to pay for building and maintaining this enormous project. Looking forward forty years, the pipeline would become national news in the 1990s, after Erin Brockovich exposed it had contaminated the groundwater in Hinkley, CA – another major PG&E scandal one of your friends might have recalled.

In the autumn of 1952 the Public Utilities Commission allowed PG&E to increase rates, but by 16% instead of the 21% they had insisted was needed. From the wire service reporting it appears the company’s inflated operating costs were not mentioned at the PUC hearing. (PG&E’s funding of ECAP did come up when they requested another rate increase in 1974.)

This is not the place to poke through all of PG&E’s dirty laundry from that era, although there’s no book or internet source that explores it (at least, none I’m aware of). Those wanting to know more will find the testimony of Robert Read and Louis Bartlett at the 1945 state water conference to be stimulating reading. This scarcity of background makes the 1952 coverage by the Press Democrat and Argus-Courier all the more extraordinary.

Credit where it’s due: Besides Lewis and Rands, we were educated by W. D. Mackay of the Los Angeles-based “Commercial Utility Service,” a watchdog group that sent letters to mayors and city attorneys about the gas pipeline. The Argus-Courier was apparently the only paper in the state that published the letter. In the Press Democrat solid information was provided by Ulla Bauers, the paper’s night editor and sometimes columnist. Because of him, we have a great Believe-it-or-Not! footnote: “Ulla Bauers” was the name of a dislikable minor character in the sci-fi DUNE universe who appears in a novella published in “The Road to Dune.” Author Frank Herbert worked at the PD 1949-1952, so the name can be no coincidence. Herbert also later wrote “The Santaroga Barrier,” a novel which takes place in a small California town where residents “appear maddeningly self-satisfied with their quaint, local lifestyle.”

TOP PHOTO: “Kitty” @blackksiren weheartit.com

PG&E ads: advertisingcliche.blogspot.com

“Letter Read to City Council” Argus-Courier, July 4, 1951“P.G.&E. Rate Case Affects Interests Of All Santa Rosans” Press Democrat, December 7, 1951

“‘Unjustified’ PG&E Costs Reported in Rate Protest” Press Democrat, January 9, 1952

“Much of P.G.&E.’s Profits Are Drained Out to the East” Press Democrat, April 1, 1952