Fresh back from service in WWII, architect “Cal” Caulkins had a vision: He would fix Santa Rosa. He wasn’t the first to try it – nor the last.

The downtown that Caulkins wanted to fix in 1945 was essentially what still exists now, sans our monstrous mall. It was also mostly the same as it was in August, 1853, when a surveyor named Shakely laid out a grid of a few streets centered around a small plaza. And that’s the problem: Once we scrape away all the built-up crust, the layout of Santa Rosa was – and still is – a mid-19th century village. The town motto should be changed from “The City Designed For Living” to “The City Designed For Living…in 1853.”

Santa Rosa quickly began to outgrow its modest framework. The next year it became the county seat, which led to a courthouse, county jail and county records building packed around the village square – and even that centerpiece was lost in 1884 when the next courthouse was built in the middle of it. Santa Rosa’s plaza hadn’t been much to look at and there were ongoing problems of stray cows and pigs taking up residence, but at least it was a public open space. Now the village town didn’t even have a park, and it would be 1931 before Santa Rosa had a true public-owned place (thanks to the donation of the nine acre Juilliard homestead).

Nor did Sonoma’s county seat have a building where lots of people could assemble. The Athenaeum opera house was used until it fell down in the 1906 earthquake; afterwards large public meetings were held at the roller skating rink, a movie theater or at the armory. The Burbank auditorium at the junior college opened in 1940 and could seat 700, but that was pitiable compared to cities like San Jose, which had a civic auditorium that could hold 3,500.

Elected officials and town boosters sought piecemeal fixes, apparently never recognizing the problem was the town’s underlying design. Another gripe concerned the narrow streets; immediately after the 1906 earthquake pulverized much of downtown, Press Democrat editor Ernest Finley pushed hard to widen all principal streets in the business district so they could accomodate electric trolley cars (only two blocks of Fourth street were modified).

Same with the park and auditorium issues; they knew a park with some amusements would draw Bay Area tourists and a large hall which could host conventions were both reliable money-makers. They spent nearly fifty years off and on trying to create a park but it always ended the same ways: The town couldn’t afford the land, they feared voters wouldn’t pass a bond or there was too much heavy lifting involved.

The solution to both problems seemed at hand in early 1906 when architect William H. Willcox proposed creating a waterpark via a dam on Santa Rosa Creek, turning it into an urban lake. It would be the centerpiece of the town with a section for swimming and water sports, benches and paths illuminated with strings of light bulbs (très moderne!) on both banks and a kiosk jutting over the water for bands to entertain. He also had designed a convention-style auditorium that could seat 2,500, which made him the darling of Santa Rosa’s business elite; they had pledged almost the full amount to start construction – and then the earthquake hit. For more on both plans, see “SANTA ROSA’S FORGOTTEN FUTURE.”

It would be almost forty years before someone came along and tried again, and that would be Cal Caulkins – who also tackled Santa Rosa’s underlying problems head-on.

Cal Caulkins’ career up to 1945 was introduced in the previous article, which explained some of the architectural styles he used and offered a walking tour of his typical work. If you haven’t read that piece it’s important to know he was Santa Rosa’s top architect at this time and a well-respected civic leader; anything he proposed would be weighed quite seriously.

The public first saw his design in the August 19 edition of the Press Democrat. The accompanying article in the PD was headlined, “Master Plan Urged for City’s Future.” A second banner over the drawing announced, “A Postwar Vision – ‘Face Lifting’ for Santa Rosa.”

Although the plan was entirely his, the germ of the idea came from Press Democrat editor Herbert J. Waters, who had published an unusual above-the-masthead editorial six months earlier. At the time there was much debate concerning the need to expand the county courthouse, with either an annex somewhere else or via adding a third floor “penthouse on stilts” to the existing building, estimated to cost a staggering $325,000 – with most of that going to reinforce the structure.

Waters was also peeved by an American Legion committee which had just asked the city to use Fremont Park as the site for their future war memorial building. Besides the loss of a scarce public park, he decried scattering new public buildings all over town just because there was land already owned by Santa Rosa. He called instead for a long range plan to create a civic center on the banks of Santa Rosa Creek. “With beautiful Juilliard Park and the famous Luther Burbank Gardens as approaches, such a civic center could be one of the most attractive in the country” – and remember that was in 1945, when the Redwood Highway went through downtown.

Although Waters’ ideas were quite sketchy, Caulkins took that vision and expanded it greatly. What he designed was simply brilliant.

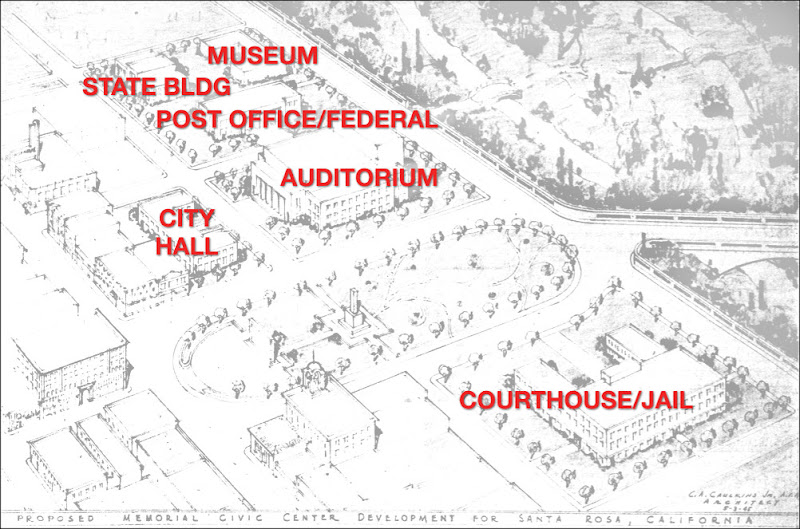

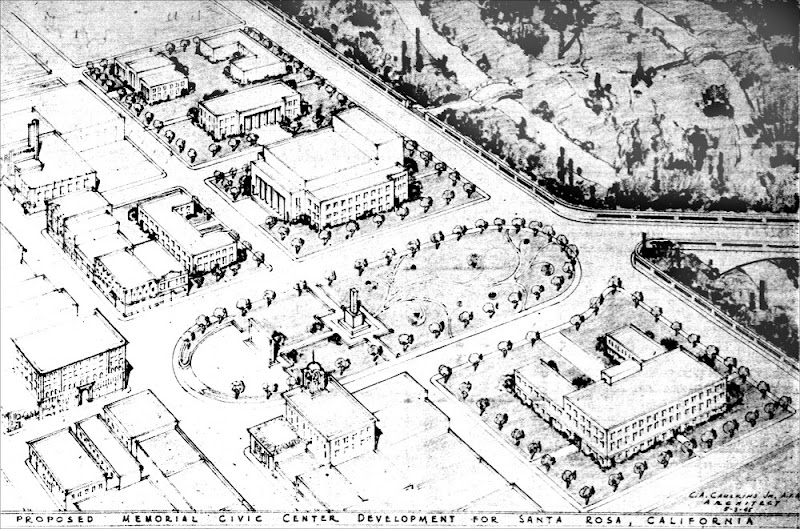

|

| Cal Caulkins watercolor of proposed Santa Rosa Civic Center. PD, June 15, 1953 |

|

| Key to Caulkins’ proposed Santa Rosa Civic Center |

|

| Cal Caulkins pen and ink drawing of proposed Santa Rosa Civic Center. PD, August 19, 1945 |

He produced both a pen and ink drawing of the plan that appeared in the PD and a large watercolor that he loaned out for display and used as a backdrop during his frequent speaking engagements that autumn.

What he was calling the “Memorial Civic Center” provided Santa Rosa new open space via a walkway to the point between the confluence of Matanzas and Santa Rosa Creeks. The undersize courthouse square was gone, replaced by a landscaped plaza stretching from Fourth street to First (although its roundabout shape might have tempted jalopy racers to think of the Circus Maximus).

Like Willcox he glorified the Creek, turning First street – long the junky part of downtown with scattered shacks, the grimier auto repair shops and farm equipment resellers – into a scenic drive as well as the main connector to the neglected working class southwest neighborhoods.

No question: This was the best of all possible Santa Rosas, and all that was needed to start the wheels moving would be for voters to pass a measly $100,000 bond.

What could possibly go wrong?

Seemingly everyone loved Caulkin’s plan. It was endorsed by the Chamber of Commerce, the Board of Supervisors, labor unions, service clubs, veteran’s groups, women’s groups and politicians of all stripes. The Press Democrat ran a banner on the front page reading, “Santa Rosa’s Future is at Stake.” It looked like a done deal.

Some of the enthusiasm was surely part of the prevailing “can do” optimism that lifted the nation from the spring of 1945 onward, once it became clear the end of the war was approaching. Everyone was looking forward to making their own little corner of the world not only whole again, but better; in Sonoma county, a committee was formed to explore creating a “Redwood Peace Temple,” which apparently was to be sort of a Bohemian Grove-ish annual summit for world leaders (albeit hopefully without those notables drunkenly pissing on trees).

Nor did there seem to be concerns about how to pay for everything. It was promised there would be cost efficiencies in clustering the federal, state, county and city buildings so close together, with money coming from all four sources. Santa Rosa was already in queue to get $500k for a new post office, there was property tax money to fund war memorials all over the county (thanks to a temporary change in state law) and besides, everything did not need to be built at once; they could start with the war memorial and build the other stuff when the money came in. Pay as you go, postwar style.

To launch the project, Santa Rosa asked voters for a $100,000 bond to acquire the war memorial site. It was a crowded ballot for a non-election year, with seven bonds worth $845k plus four other items, but nothing was pushed harder for approval than the war memorial. In the weeks before the vote hardly a day went by without an item about it in the Press Democrat; we were told it was a good investment because it would attract conventions and the (expected) matching grants would make construction virtually free. A coalition of veteran’s groups formed a joint committee to get the voters to the polls. And although December 4 ended up being a miserable day with a hard rain, half of all registered voters turned out.

It lost by 96 votes.

The PD was editorially silent about the defeat, but it was the #1 topic in letters to the editor for the rest of the month. A single writer cheered its failure; another person begged for someone to explain what happened – but mostly people pointed accusing fingers at the American Legion.

Simply put, there was distrust about the Legion’s involvement with the War Memorial project. This came up right after Caulkins’ plans were published, when County Supervisor Guidotti remarked, “…only recently a group of Santa Rosa legionnaires appeared before our board and their spokesmen, in effect, admitted that they only wanted a building for themselves and to [hell] with anybody else.” Similarly, when the legionnaires earlier proposed the Fremont Park site to the Santa Rosa city council, they were asking the city to use its share of the tax money to build them a meeting hall along with granting a 99-year lease. They would not commit to allowing other veteran’s groups to use the building and it was an open question whether they would even let the general public use it. Leaders from the VFW and the Disabled American Veterans were at the meeting to complain they were locked out of discussions.

One letter writer was generally incensed by the “apparent attitude of the Legion toward veterans of World War II,” noting that the Legion in San Francisco had recently refused the American Veterans Committee (AVC) use of the war memorial there. (Now defunct, AVC was a progressive group focused on problems facing WWII vets, particularly homelessness.) The Legion claimed they denied access because AVC was not “pure” since merchant marines could join, but one might also wonder if that was a sneer at AVC for being racially integrated, while the American Legion had separate posts for white and black veterans.

Whether the legionnaires should be blamed for killing the Civic Center project is moot. Without that $100,000 there would be no war memorial downtown – and with that, the dream of a Santa Rosa Civic Center was dead. Its failure to pass left a county supervisor questioning if taxpayers wanted those war memorials at all. What happened next was covered here in “THE VETS WAR MEMORIAL WARS:” Soon after the county bought some land in the Ridgway neighborhood for the Santa Rosa auditorium, and when that didn’t work out decided to build it across from the fairgrounds.

But Caulkins’ Civic Center was not forgotten; for years, mentions kept popping up in PD letters-to-the-editor as well as in articles and columns whenever the subject of downtown improvements came up. His watercolor was displayed in a window of Rosenberg’s Department Store in 1951. When in 1953 the county began making plans to build an administration center north of Santa Rosa city limits (at its present location), the Chamber of Commerce and others urged the supervisors to consider a scaled-down version of Caulkins’ downtown design. Caulkins told a reporter he was “besieged” with calls afterwards and the PD ran an illustration of his color drawing alongside an article about it.

There were other attempts to fix Santa Rosa’s design problems in 1960-1961, when the city’s new Redevelopment Agency hired urban design experts from New Jersey. Some of their ideas were pretty good; they envisioned a pedestrian-friendly city with mini-parks, tree-lined boulevards and a greenway along both banks of a fully restored Santa Rosa Creek. Their objective was to improve traffic circulation so the public could drive as quickly as possible to a parking garage/lot and walk from there. In a nod to Caulkins’ work, they proposed the combined county courthouse/jail in a park-like setting on the south side of Santa Rosa Creek.

To their credit, the NJ experts were concerned that Roseland was cut off from the town and wanted a highway 12 exit for Sebastopol avenue/road; to their shame they first proposed eliminating courthouse square, then chose to cut through the center of it. But this is not the time to further discuss the 1960s urban renewal misfires – that will require another lengthy essay or three.

Nothing in the Waters-Caulkins layout survives, except for the removal of part of Second street. (For those like me who have always wondered if that section of the street disappeared in order to wipe out any trace of the old Chinatown, Herb Waters admitted as much in his 1945 editorial: “Our former ‘Chinatown’ in Second street comes as close to slums as anything we have in Santa Rosa, and its removal would certainly occasion little economic loss.”)

But the Santa Rosa that exists today bears little resemblance to what any of those 1960s experts designed, either. Santa Rosa Creek was entombed in a box culvert, although that was the natural feature everyone wanted to highlight; what government buildings that are still downtown are a mishmosh of styles, most already badly dated. While beneath it all, the old grid of village streets from the 19th century still constricts us in the 21st. And no, we can’t blame any of those bad decisions on the American Legion.