“Did’ya see it?” Was likely the question everyone in Santa Rosa asked that Saturday in 1924. “It” was the car driving through the streets all night with a flaming cross attached to the hood, while the passengers tossed cards announcing the Ku Klux Klan was here and not going away.

In the mid-1920s Sonoma county had the reputation of being the hotspot of Klan activity in the Bay Area – which was a kind of homecoming, as the fledgling KKK would have died on the vine if not for the man who used to be the county’s PR representative.

(RIGHT: The KKK left calling cards to intimidate and lay claim to a presence in the community)

This article really should be titled, “The SECOND Klan in Sonoma County” because an earlier generation of the Boyz n the Hood(s) was active here after the Civil War, and before that the seditious Knights of the Golden Circle were causing trouble during the war itself.

The second Klan was started in 1915 after a handful of men in Georgia were stirred up by D.W. Griffith’s groundbreaking film, “The Birth of a Nation,” with its deeply racist portrayal of the Reconstruction era. In that twisted version of history, the “night riders” were not lynching and terrorizing the black populace but restoring justice for southern whites being victimized by former slaves.

During and after WWI the new Klan sputtered along adding only a few thousand members in the Deep South, although conditions were ripe for such a hate group to flourish. National discontent was particularly high during the “Red Summer” of 1919 when whites in about two dozen cities and town rioted, murdering several hundred African-Americans (some war veterans were lynched in their uniforms). There were thousands of labor strikes nationwide amid growing fears that we were on the verge of a Bolshevik-style revolution. Now toss into this kettle of fear and fuming anger a heaping portion of conservative resentment over women gaining the right to vote plus the general misery over the start of Prohibition.

The turnaround came about when the founder of the new Klan met PR agent Edward Young Clarke. A ne’er-do-well member of a prominent Atlanta publishing and newspaper family, Clarke had helped promote a few charities (and was sued by one for embezzling) but his main job reference was as protégé to Mondula “Mon” Leak, who founded the Southeastern Exhibit Association in 1917. The stated objective was to use a warehouse-like exhibit hall in downtown Atlanta to advertise Georgia places, products and services. The initial promotions seemed pretty random – a roofer, a company that made tents and a handful of chambers of commerce, for example. What all of them had in common was a sucker’s readiness to pay membership dues to Leak’s phony association.

This was a scam Leak had perfected when he was representing Sonoma county and other North Bay counties between 1909 – 1915. He was supported by dues from all our local Chambers and trade groups to promote the region in a traveling exhibit from a custom-made railcar, but the real attraction was another car on the train with a zoo/curiosities show where Leak charged admission. Presenting a little table boasting “the creations of Luther Burbank” and redwood bark gave him enough legitimacy to claim his exhibits were “educational” and avoid the taxes and fees communities usually charged carnival sideshows. In short, he was really a low-rent P.T. Barnum. The whole strange tale was told here earlier in “SONOMA COUNTY, FAMOUS FOR SHARKS AND LUCKY BEANS.”

Part of the genius of that scheme was that Leak didn’t collect dues from each town himself, but had a contract with an umbrella organization – the North Bay Counties Association, which later became the Redwood Empire Association – to do the job for him. That way, when a local chamber of commerce didn’t want to pay and complained they weren’t getting much bang for their buck (here’s looking at you, Healdsburg) their compatriots would shame them for not pulling their weight.

In his Georgia operation, Leak eliminated the middleman by creating his own association. Further, he told newspapers he planned to expand the association to include other southern states, where presumably mini-associations with a Leak director would sign up members, collect dues and funnel that money back to the Atlanta mothership. Essentially, he turned it into a sales network working on commissions.

After a couple of years Leak retired and handed the operation over to Clarke. All the historians seem to dismiss Clarke as something of a nitwit or at best, a lousy con artist, but I disagree. Clarke – or someone close to him – quickly took the Ku Klux Klan from its origins as a small, funky social group to an army of hate-driven zealots, and he did it by weaponizing Mon Leak’s plans.

Just as Leak created the Southeastern Exhibit Association as a front to sell memberships to town chambers and trade groups, Clarke and the national KKK were funded by regional “Realms” pooling contributions from local “Klaverns.” Now to join the Klan you had to pay (er, donate) dues, and it wasn’t cheap – ten dollars, or the equivalent to about $140 today. Of that $10 (which they called a “klectoken”), the largest chunk ($4) went to the local organizer, so he could work fulltime enrolling new members. His supervisor received another buck from the dues; the two of them were called, respectively, the Kleagle and King Kleagle. The regional manager was the Grand Goblin who was given fifty cents, and $2.00 went to the national organization. The rest went to Clarke personally, as he was now the Imperial Kleagle. In the hierarchy were also the Klokards, Kludds, Kladds, Kligrapps, Klaliffs, Klabees, Klexters and I swear I am not making up any of this krap.

That was at the end of 1920. In the months that followed Klan membership snowballed, as did the coffers of the organization. And it wasn’t just from membership dues; you were required to buy all your Klan swag from headquarters, including the robe, books, pamphlets, cardboard red crosses and little cards to scatter around your town announcing the Klan was there, plus other awful goodies. Soon Klan HQ was pulling in million$ a year and growth was exponential, with about four million guys wearing hoods by 1924.

Like most Americans, our local newspapers didn’t quite know what to make of the Ku Kluxers, but were definitely Klan curious. On its face the KKK was not much different than other fraternal orders like the Elks or Odd Fellows (sorry, gents) with a costume, secret handshakes and other silly rituals. Without explaining the real aims of the organization, the papers uncritically printed stories about their gatherings. This 1923 item from the Petaluma Argus announced the Klan had a North Bay presence:

NAPA, April 4 – More than 1000 hooded figures of the Ku Klux Klan gathered somewhere in the hills of Napa county, participated in a strange ceremony round a fitfully flickering fire, silently and swiftly gathered their robes about them and disappeared into the night, as mysteriously as they appeared… |

Then before Hallowe’en, the Press Democrat ran a screamer headline, “104 JOIN KU KLUX ORDER.” The front page article similarly pushed a idealized view of the KKK and their “awe-inspiring” ritual:

…Two hundred hooded klansmen, seeming phantoms in the pale moonlight of the evening, participated in the initiatory ceremony. Prior to the exercises only one or two of the masked klansmen, attired completely in white, were seen on the grounds. As if from nowhere, the 200 robe-clad figures marched from behind a small hill…ghost-like figures walked across the field while the figure of a klansman on horse back was silhouetted against the sky. A short time before the initiatory ceremony started, a huge cross, approximately 20 feet in height and situated in back of the American flag, was lighted, its rays shining on the line of hooded klansmen who walked to the small knoll… |

|

| Undated photo not in Sonoma county, but matching the 1923 ceremony described |

The PD estimated there were about 300 cars of spectators watching the event. Among those swearing allegiance to the KKK were sixteen from Mare Island wearing their Navy uniforms.

About three weeks later was the first ceremony held in Sonoma County, on a hillside off Petaluma Hill Road. An estimated 2,000 people came to the invitation-only event. There were so many cars that afterwards, the PD said, “…traffic congestion at the exit gate for a time resembled the worst congestions of the old Cotati speedway days.”

Sonoma county’s widespread interest in the Klan in 1923 might be surprising, since a Klan organizer held a couple of meetings in Santa Rosa in 1922 but couldn’t draw much interest. And earlier that year, the PD had a scare headline “KU KLUX THREAT IN SONOMA COUNTY?” hyping news that a deputy had received an anonymous threat warning him to stop arresting troublemakers at Forestville dances. The deputy didn’t take it seriously and presumed it was written by the selfsame jerks. There were at least two other hoax KKK threats reported that year.

The splashy 1923 ceremonies were the peak of the Klan’s public events in Sonoma county, with a smaller initiation on Bennett Valley Road in June 1924 (the cross this time illuminated with light bulbs) and later in November, 25 women were initiated as members of the “Kamelias” in Santa Rosa.

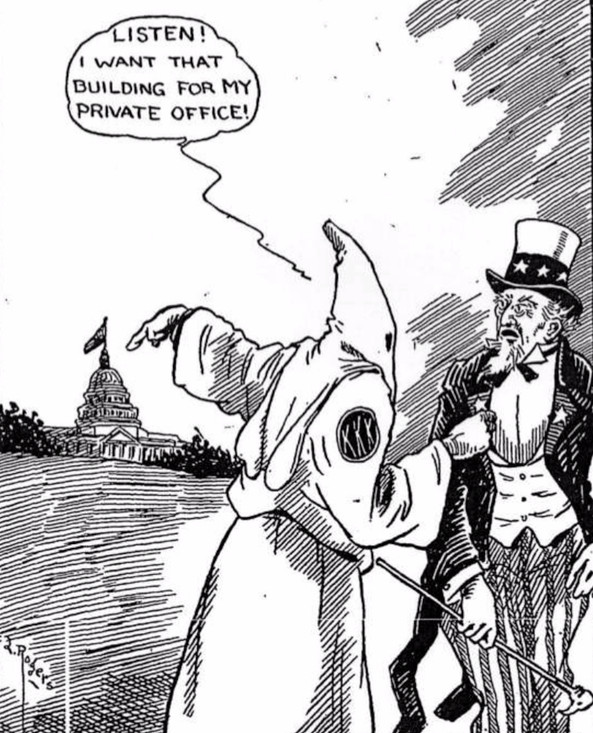

(RIGHT: 1925 cartoon from The Rocky Mountain American, a KKK newspaper in Colorado)

But the KKK was quickly worming its way into everyday life. They donated food and other items to families with ill Klan members in Santa Rosa and Petaluma, and they presented a bible (“valued at $50”) to the Calistoga library. They held a “Ku Klux Klan funeral” for Santa Rosa resident William J. Reno, complete with reading from the book of Revelations and “vocal music of a hidden chorus.” And after a defense attorney accused the District Attorney of being in cahoots with the Klan to railroad his client, a prospective member of the jury volunteered he was also a klansman.

None of the Santa Rosa and Petaluma newspapers editorialized against the KKK, as far as I can tell, but all gave front page coverage to negative stories about Klan confrontations, legal and political, happening elsewhere in the nation. They also reported positive stories as well; one of the oddest photo captions I have ever read appeared in the Petaluma Argus: “Jew is Honored by Ku Klux Klan,” describing how dozens of hooded klansmen showed up uninvited to a tribute for an elderly shopkeeper in Fairfield, Illinois, handing him a basket of roses.

And neither did the local papers explain to readers everything the KKK really stood for. Describing the big Petaluma Hill Road ceremony, the PD mentioned in passing that new members were told support “supremacy for the white race, separation of church and state, and rigid law enforcement.” Of the same event the Petaluma Courier said the Klan pledge was about “Americanism” and law and order.

The most information came the Petaluma Argus, which offered a lengthy account of a late 1924 Klan recruitment speech given at the high school. “It is a white, native born, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, patriotic fraternity. Orthodox Jews cannot join because they do not believe in the divinity of Christ.” (The speaker apparently forgot to mention Catholics were a main target of the hate group.)

The Klan was also a militia, he told the packed auditorium. “All Klansmen may be called upon by the governor at any time to keep law and order; the sheriff may call on them. In case of emergency, the governor may call on the Klansmen of California and over 350,000 would be ready to march at sunrise.” The speaker did not say what they expected to be called upon to defend, but did mention they wanted “to see that the immigration law is enforced.” He said they were currently “fighting appalling condition in the negro sections in many large cities,” according to the Courier, while noting there were over three million “half-breeds” in America. He stated the Klan “does not practice acts of violence,” but added “flagrant law violators should be hanged twice.” And there, Gentle Reader, was the dog whistle to those in the audience who thought it might be kinda fun to wear a disguise and act out as a homicidal vigilante.

The speaker even flashed some Klan humor by pointing out their hoods only had holes for the “watchful eye” because a klansman was supposed to stay silent. “How many of you husbands in Petaluma would like for your wife to have a silent tongue?” The newspaper felt compelled to add that he said it “jokingly.” There were also local nods: “It is just an necessary to raise good children as it is to raise good chickens,” he said, inviting boys to join their group for kids called the “Kluckers.”

Klan activity declined quickly after that in Sonoma county, as it did elsewhere in the nation. In 1925 there were only two ceremonies reported in the papers, one across the road from the Vallejo Adobe in Petaluma and another in a field south of Barham avenue in Santa Rosa, which is presumably the CostCo shopping center today. Attendance was lower because Napa and Vallejo klansmen “were reported to have become confused on the road and failed to arrive.”

The last mention of the KKK locally came in 1930, when a motorcade stopped in Petaluma after a ceremony somewhere in Napa. While the Klan’s first ceremony there in 1923 drew a thousand people, the best they could now muster was a hundred. The klansmen and their family had supper in Petaluma and left, but not before scattering everywhere their little cardboard red crosses. Once intended to express power and incur fear, it was now only trash littering the streets.

|

| “Sooner or Later” cartoon from the African-American newspaper The Chicago Defender, 1923 |