If it can be said that there was a renaissance period of American architecture, then it had to be San Francisco in the 1890s. The city was vibrant with possibility; buildings were being designed that had never been imagined before. And in the middle of this was a twenty-something young man from Petaluma who was absorbing it all.

(This is the final part of a presentation made at the Petaluma Historical Library & Museum on October 20, 2018. Part one, “THE MAKING OF BRAINERD JONES,” explained how Queen Anne style and Shingle style architecture came about and became the groundwork for his career, and that his early clients were likely hyper-literate about trends in modern architecture because of the profusion of articles in popular magazines.)

Was Brainerd Jones a genius? A genius is not simply a person with a big grab bag of tricks and techniques. Whether he was a genius or not I can’t say – but he was certainly a very fine architect.

Or can we say any of his work qualifies as a masterpiece? A masterpiece is more than the sum of its parts, checking off items from a list of what’s considered attractive and pleasing – at the time. To weigh the merits of a work of nice architecture, I like to play a game called, “How easy would it be to screw this up?”

|

| Today’s Petaluma Historical Library & Museum |

|

| Santa Rosa’s 1910 post office (now the Sonoma County Museum) is a Beaux Arts-Neoclassical-Spanish Colonial mashup with a tile roof and a portico with Corinthian columns. (MORE) |

|

| Why not a clock tower for an important public building like the town library? In 1907, John Galen Howard, one of the top architects on the West Coast, designed a lovely Beaux Arts building for a bank in downtown Santa Rosa. But the elegant architecture became merely a base for the clock tower that harkened back to the too-busy Second Empire style from about forty years before. (MORE) |

Brainerd Jones was born in Chicago in 1869, moving to Petaluma at age six after his father died. As a teenager he was recognized at the local fair for his drawing skills and his ability in “netting,” which is a kind of crocheting. He supposedly took art lessons from Max Roth, a marble cutter and monument maker who had a yard on Western ave. The first sighting as an adult (at least, that I can find) is as a carpenter in Tiburon in 1892, and a carpenter in San Mateo the year after that. His first known professional gig was as a draftsman in 1896 for the construction firm McDougall & Son. This was not a prestigious place to work; although their main offices were in San Francisco, between 1894-1897 most of their work was around Bakersfield building hospitals, schools and jails. The successor business, McDougall Brothers, became quite important after 1906 and remained so for the next twenty years. That was long after Jones was gone, however.

|

| The San Francisco that Brainerd Jones knew was still a gaudy party town, but by the mid 1890s it was quickly developing a reputation for cultural and intellectual advancement. The 1894 Exposition in Golden Gate Park celebrated the city’s progress and drew 2.5 million visitors. |

|

| This world’s fair also brought the city its first art museum with this odd, neo-Egyptian building which became the de Young after the fair. It was destroyed int the 1906 quake. |

|

| Jones’ first known commissions came from sisters Mary Theresa and Helen Burn in 1900 and 1901 (MORE on the Burn family). They lived in Petaluma from 1900 to 1907, but why they came here is unknown; they previously lived in Chicago and were originally from the Kitchener, Ontario area. Mary – who went by the name, “Miss M. T. Burn” – had a business on Main st. where she taught and sold “fancy work” (embroidery). The four cottages they commissioned were scattered on both east and west side lots. One is definitely lost, one can’t be found (and may not have been built) and one has been heavily modified. |

|

| The Byce House at 226 Liberty street also dates to 1901. It’s mostly a conventional Queen Anne with a corner tower and the usual fish scale shingles. |

|

| The window pediments and ornamental molding around the attic window are neoclassical, but all the finials are gothic, as is the metalwork around them on each gable. |

|

| Jumping back to 1901, a third Queen Anne built that year was the Lumsden House at 727 Mendocino Avenue in Santa Rosa. Today the front view is obscured by mature foliage |

|

| The stained glass seen earlier was from the Lumsden House; here is another example. |

|

| Although the building was torn down in 1969, its footprint can be seen on the old fire maps. Guesstimating from the irregular shape, Paxton House was between 6,500 and 7,000 square feet – the largest residence Jones ever designed (MORE). As far as I know, Jones was the only architect who designed in both the popular Queen Anne style and the more artistic Shingle style. |

|

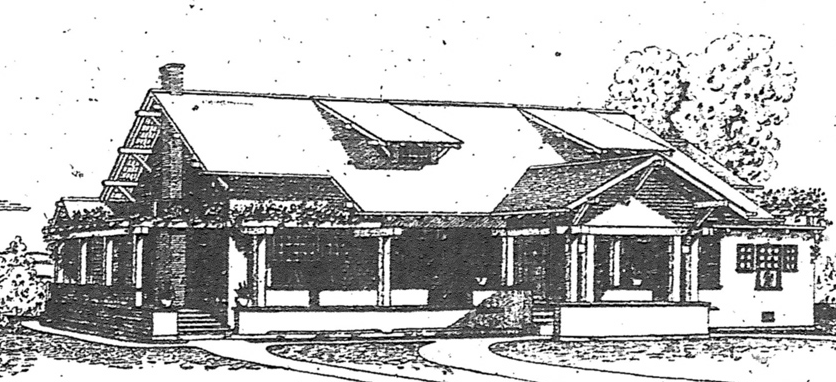

| Several houses Jones designed in the 1910s seem derived from Stickley’s Craftsman Homes, but he was very much in touch with other modern trends. His 1908 design for the Saturday Afternoon Club in Santa Rosa (MORE) was in synch with the the Arts and Crafts movement’s cottage style now called “First Bay Tradition.” |

So let’s ask again the questions I raised at the beginning.

Was he a genius? It’s jaw-dropping that he accomplished this work with his minimal training and education apparently limited to what he read in magazines and saw on the street. Yes, his lack of engineering caused some of his buildings to be flawed, but so were many of the works of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Were his designs architectural masterpieces? I would argue the Petaluma Museum qualifies. It’s neoclassical but also original, with yet another take on deconstructed Palladian windows. And then there’s the stained glass dome – something usually found in upscale hotels and businesses or churches. And that raises another “how easy it is to screw up” test; since this is a library and patrons are supposed to be looking down at books, wouldn’t clear skylights and hanging drop lights be more practical?

I believe every home he designed was considered a masterpiece by its original owner. Each was designed to fit their tastes and lifestyle like a glove. Mrs. Brown obviously wanted an old-fashioned design and Jones gave it to her, yet without larding on Victorian ornamentation. Blitz Paxton wanted the biggest house in town so he and his wife could throw lavish parties. And Jones gave him that, plus an ultra-modern look which dialed it up to bring attention to his ostentatious lifestyle.

That, I think, was Brainerd Jones’ real genius; he listened intensely to his clients so as to fully understand what would make them happy. The design became a collaborative effort.

And this also shows he deeply understood the principles of John Ruskin. When you live in a house that has been put together thoughtfully – even a simple California craftsman cottage – it has an impact on your outlook every day. Coxhead, Polk, Maybeck and other California architects at the time also knew this; it was about something deeper than picturesque street views – it was about creating art someone actually lived in.