Once upon a time Santa Rosa had a rival village next door named Franklin Town.

Or not.

The often-told story goes something like this: In the early 1850s, before there was a place called Santa Rosa, Oliver Beaulieu founded a village somewhere near the Carrillo adobe. He named it Franklin after his brother. A church was built and there were a handful of businesses (tavern/inn, blacksmith, etc.) plus a like number of houses. In 1853 Julio Carrillo, along with three other men, laid out a street plan about a mile to the west for a town they called Santa Rosa.1 After it was declared the new county seat the following year, the denizens of Franklin began rolling their buildings to Santa Rosa on wheels. By 1855 or so, all of them – including the church – had been moved. There was nary a trace of Franklin left.

Twenty years passed before any of that Franklin history was told, although that’s not particularly surprising. When it faded away there was only a single weekly newspaper in the area (the Sonoma County Journal in Petaluma) and even Santa Rosa was scarcely mentioned in its pages – why waste ink on a defunct settlement? But once local area histories began being written in the mid 1870s, there was always a passage about Franklin. As the years went on those mentions kept getting longer as historians cribbed from their predecessors and tossed in more details. If you added up all the varied claims (transcribed below) there were up to three stores, a couple of taverns, a hotel, a blacksmith or two, the church, a wagon shop and a saddle tree factory.

None of the historians cited where they got their information, and only one could have possibly visited the short-lived Franklin (Robert A. Thompson, who began living near Petaluma in 1852). At the same time, that lack of a firm narrative also lends the story an air of mystery – which is why we’re still talking about it today.

Questions abound: What appeal did Santa Rosa have that Franklin lacked? Why were the residents quick to abandon it? Did Beaulieu actually intend to establish an incorporated town? And what’s the deal with the name “Franklin Town?” That’s just the top of the list.

We know some answers and can make reasonable guesses at others, but there are also blind alleys. Beaulieu supposedly had about half a square mile surveyed, but the map is lost (if it ever existed). He moved to Santa Clara County and years later a lengthy profile appeared in that county’s history book. Subjects paid a good deal of money to get their bio and picture in those “mug books,” so it’s a sure thing it tells his lifestory as he wanted – and it didn’t mention Franklin at all. As for the story it was named in honor of his brother, that didn’t appear until 1880 and came from a non-local historian who cranked out a book for a different county every year.2

Come the 20th century, the story of Franklin became further muddled. One historian said most of the buildings were “small split redwood shanty-style” dumps without doors or windows.3 (Henry Beaver, who had a two-story brick house would like to have a word about that.)

Assumptions about its general location grew fuzzy; one historian placed it a mile east of the Carrillo Adobe. Hunting for clues as to where it was, SSU grad student Kim Diehl chopped through a tangle of deeds with cryptic landmarks such as a “fir red oak” and “where the road formerly crossed the creek.”4

Even rough map identifiers such as the locations of roads aren’t always helpful. Unmarked trails became roads and some of those roads took more than one name over time. The earliest historical description put Franklin at the “junction of the Sonoma road with the Fulkerson lane.” Okay, so it’s an easy assumption that “Sonoma road” is the road to the town of Sonoma – but where was “Fulkerson lane?” Was it the same as the “road to Mark West’s farm?”

Without ranking those historians by their hits and misses, let me just repeat that the internet has brought researchers an age of miracles and wonders. Rare maps are just a click or tap away, and the power to completely search heritage newspapers turns up references where no one would otherwise look. Thus with the aid of the three annotated map segments below, here’s the Executive Summary of Frankin’s location:

Franklin Town was close to the present site of the Flamingo Hotel and Hillside Inn, catty-corner from the Carrillo Adobe and across Santa Rosa Creek. This was near the intersection of three major roads/trails leading east, west, and north. The Sonoma Road is roughly the same as Highway 12. What they called the Bodega Road is now Fourth St. Fulkerson Lane – AKA Russian River Road and Cemetery Lane – is known today as Bryden Lane, which then passed the Rural Cemetery on its way towards the Old Redwood Highway.5

A high number of cartography errors are obvious, such as the distance between the Sonoma Road and Santa Rosa Creek. But we can still situate the Carrillo adobe with some accuracy. We can narrow down the approximate location of Franklin Town as being consistently described on property later owned by Lucas and Simms. (The Carrillo adobe is represented by the icon ![]() and is not pictorially accurate to what it looked like).

and is not pictorially accurate to what it looked like).

The name has a more complex explanation, but one key to the puzzle is that it was referred to as Franklin Town and not simply Franklin. Yes, it’s possible it was in honor of Beaulieu’s brother who had a name which was sort of similar (see fn. 2) but it’s more likely that Beaulieu wasn’t the person who named it. Evidence suggests it was actually called that because of a guy named…Franklin.

A quick refresher in 1850s Sonoma County will be helpful. The area was sparsely populated yet steadily filling up with settlers who were homesteading farms and cattle ranches, but only a lucky few had legal title to their places. Some leased acreage or had other deals with the landowners but most were squatters, possibly unaware who actually owned the land. (Here’s an excellent contemporary summary of the “squatter difficulties” at the time, plus an account of visiting the Carrillo’s at their adobe.) The squatters were in turn scammed and exploited. Charles Justi – who we’ll meet again in a few moments – thought he owned 500 acres near Glen Ellen but ended up with just 40. Violence was not unheard of; a deputy sheriff was killed near Healdsburg and a confrontation at Bodega Bay came close to a shooting war.

All of that meant plenty of ongoing legal doings. And since the county courthouse was then in the town of Sonoma while most of the squatters lived north of there, the Sonoma Road was one very busy thoroughfare. It was a time-consuming trip by buggy or horseback; two hours between (future) Santa Rosa and Sonoma was considered good. Should your land claim be further north – say, near Geyserville – add a couple more hours to that.

Along that entire length of road there were only three places for a traveler to stop – remember: no Santa Rosa yet. Part of the Carrillo adobe was used as a tavern called “Santa Rosa House,” which lasted until sometime in 1853. About three miles further along modern Hwy. 12, near the turnoff for St. Francis Road, was Bear Flag House. Owned by Bear Flagger W. B. Elliott (absolutely no relation to this author) this was a tavern and a very significant place in early county history. Even before official statehood the Democratic party hob-nobbed there to decide how they would administer the county and who was to run for office. Any researcher looking into pre-Civil War politics in Northern California should beeline to learning about what went on there.

But those taverns were just a room in someone’s house and it’s not clear whether Elliott’s was even open most of the time, as he also had a cattle ranch near Mark West. Until he reached the town of Sonoma, the only chance for our weary traveler to rest came when he reached Half-Way House, about two miles south of today’s Kenwood.6 Here was an actual hotel where you could stay the night, have a hot meal and likely a hot bath. It would soon be a main stagecoach stop, in part because there was a barn where the drivers would board horses.

The owner and operator of Half-Way House was William F. Franklin.

Is he the Franklin in Franklin Town? The strongest evidence comes from a primary source: His son, William Jr., who lived here at the time and returned for a visit in 1925, when he gave an interview to the Press Democrat. He was adamant it was named after his dad.7

While Franklin Town and Half-Way House were a few miles apart, it’s easy to see how there could have been a connection. William Franklin was well known because of the hotel and in the 19th c. unincorporated spaces often became associated with the name of an early settler. Many are still in use today: Dillon Beach, Eldridge, Schellville, Marshall, Stewarts Point, etc.

Nor was there much distinction in the early 1850s between (what we call today) the Valley of the Moon and Santa Rosa Valley. The countryside all looked about the same and was used the same – a patchwork of small family operations aimed at producing things to feed San Francisco. Given that Franklin’s hotel was a rare landmark, it’s not completely surprising people might have associated a swath of eastern and central Sonoma County as being an unofficial district known as Franklin.

That would go far to explain why the earliest references to the settlement were Franklin Town and not just simply Franklin – it’s the same way we use today “the town of Sonoma” or “Sonoma City” to distinguish it from the overall county.

Pondering what they called the village in those days is like a parlor game; it’s fun, but really doesn’t mean much. The question of why Franklin Town was abandoned isn’t so trivial, in major part because generations of historians have mused it offered serious competition to Santa Rosa emerging as the dominant community in the area. One historian even went so far as to (irresponsibly) suggest there was an untold “Dark Tale of a Lost City.”

Yes, the residents of Franklin Town did migrate to Santa Rosa, but it wasn’t because the Franklinites were seeking the ceaseless joy of living near the jail and courthouse. Santa Rosa’s gravitational pull began even before the vote to make it the county seat. There were a combination of factors why it happened; Santa Rosa did have features that made it a more desirable place to live, while at the same time Franklin Town began facing setbacks that made it harder to remain there.

We credit the founding of Santa Rosa to Julio Carrillo and three ambitious shopkeepers turned real estate developers. True enough, but Franklin Town couldn’t compete because it had nearly reached its limits for growth – the area where Beaulieu and others expected Franklin Town to grow was prone to flooding.

In her last will, Doña María Carrillo referred to the land above Santa Rosa Creek as “the swamp.” Sold to Beaulieu after her death, he in turn sold it to John Lucas.8 When Lucas died and the farm was subdivided and sold off years later, an overview printed in the Democrat described more than half as “bottom land.” The crossroads may have stayed reasonably dry but more at risk was the section around today’s Proctor Terrace. Concerns about its flooding can be found when the deal was made to accept the adjacent Rural Cemetery to be the local graveyard. The citizen’s committee top concern for that specific location was “not subject to overflow in time of high water.”

The year 1853 was pivotal in the conflicting futures of Santa Rosa and Franklin Town. In the latter’s favor the church was built (the first one in the area) and the nearby trading post at the old Carrillo adobe was busier than ever. Over in Santa Rosa, Carrillo and the other three began laying out streets for their possible future town.

There are no local newspapers from that year, so we don’t get to eavesdrop on the arguments being made for one location over the other. But we do know the winter of 1852-1853 had been extremely wet (according to San Francisco weather stations), with Nov-Dec setting close to the all-time record. If the swamp/bottom land was indeed underwater, that had to influence plans to continue development around Franklin Town.

Meanwhile, Santa Rosa was forging ahead with new construction. In early 1854 a small hotel opened along with a general store. A Masonic Lodge was chartered, which was quite a big deal considering the village only had three houses. (Petaluma wouldn’t establish their Lodge until the following year, despite being far larger with several hundred residents.) Most importantly, Santa Rosa had a livery stable and Franklin Town didn’t. In that horsey age when nearly everyone rented horses and buggies to travel, having a stable nearby gave Santa Rosa a major advantage.9

Few seemed to recognize it at the time, but the scales tipped decisively towards Santa Rosa later in 1854, when the Board of Supervisors made it the county seat. Gentle Reader might assume that would be a net advantage for Franklin Town, as it was now “closer to the action” (as it were). Not so. Traffic on the Sonoma Road dropped sharply. No more squatters en route to the Recorder’s office stopping somewhere to wet their whistle. Gone were plaintiffs heading to court when their horse threw a shoe and needed attention from a blacksmith.

The first to cut his losses was Elliott, owner of the Bear Flag House. The tavern stayed around (it’s shown on the 1866 map) but he and his family resettled in Lake County sometime in 1854. The next major landowner to go was Beaulieu, who moved to San Jose in 1856. That same year the church was taken to Santa Rosa “on wheels and hauled there by six yoke of oxen.”

Sadly, the history books don’t always tell those parts of the story accurately. Instead you’ll find the writers compress the timeline and portray events happening closer to 1854 than they often did. The worst offender was Robert A. Thompson, who offered the first account about Franklin Town and claimed “within the year [1855] all the houses in Franklin were moved to the new county seat.” There was no parade of buildings trundling their way westward; the church and a couple of houses may have been the only structures that were moved and it happened later.

Nor did business and development in Franklin Town abruptly cease. Ads in the Democrat show Henry Beaver continued operating his brickyard there until at least 1858. Sterling T. Coulter (AKA “Squire Coulter”) built a home in 1854, though sometime later he did roll the place to Santa Rosa, where it first stood on Exchange Avenue and then another location for over fifty years – so much for the town being nothing but shacks.10

| – | – |

THE FORGOTTEN MR. FRANKLIN William Sr. became a naturalized U.S. citizen at Sonoma in 1858, just a few days after he first advertised to sell the hotel. As he continued efforts to find a buyer, he became secretary of the Sonoma Quicksilver Mining Company which had a mine at Pine Flat near the Geysers. In 1861 the company held monthly meetings at Half-Way House and was eventually sold to New York investors. When Ann attempted to divorce William in 1869 they were no longer living together. In the 1880s they both became indigents, with him at the Sonoma County Poor Farm and she receiving a county stipend in Petaluma. William found work as some sort of engineer in San Rafael, but died in 1890 as a resident of the Marin County Poor Farm. He is buried in an unmarked grave at the cemetery there while Ann has a proper tombstone at Petaluma’s Cypress Hill. |

But the worst shortcoming in those histories was failure to write anything about the village’s (supposed) namesake, William Franklin. Even if the place really was an anglicized version of one of Beaulieu’s many Canadian brothers – which seems like a stretch – Half-Way House was still an important landmark in early county history and deserved a nod.

Half-Way House remained open as the other early settlers moved on, but it wasn’t by choice. Franklin first placed an ad in the Democrat listing it for sale in 1858 and kept running the classified intermittently for years, becoming more desperate (“…will sell the above place VERY CHEAP FOR CASH!”) as time went on.

Apparently William and Ann separated in the mid 1860s, with her continuing to operate the hotel after it was leased to neighbor Charles Justi.11 William still owned it until 1868 when the county auctioned it off because of an unpaid tax bill of $8.18 (less than $200 today).

By then, Franklin Town was certainly gone. Beaulieu sold most of the property ID’d as the village to John Lucas in 1857, although Coulter, Beaver and possibly others still owned parts of the dwindling settlement.

So what should obituaries for Franklin Town say? To my mind there are three takeaways:

|

It was never a “rival” or in any way a challenger to Santa Rosa’s emergence. As discussed above, the first Santa Rosa area settlers invested in core businesses – store, stable, hotel, etc. No one in early Franklin Town seemed to have such ambitions, perhaps because potential flooding limited opportunities for development.

|

|

Aside from the brickyard and the saddle tree maker, Franklin Town’s commerce centered on servicing travelers going to and from the town of Sonoma. It was like a laissez-faire version of a modern highway truck stop – a place where you could knock on a door to buy a quick snack or flagon of cider, have a guy grease your squeaky wagon wheel, visit a proper outhouse. Once Sonoma was no longer the county seat that traffic dried up. After that happened in 1854 those residents and their little businesses drifted away with none to take their place.

|

|

The church filled an important social function as a gathering place for settlers all over central Sonoma County, being at such a well-known crossroads. When it moved to Santa Rosa in 1856 Franklin Town lost its final excuse to exist.

|

Franklin Town came and went quickly; anyone wanting to bookend it can summarize the years 1851-1859 as pretty likely. There were scarcely more than a handful of buildings counting the church. For a settlement so short-lived and tiny it may seem unusual that historians kept its memory alive, but the novelty of moving a “town” makes for a good story.

Perhaps, too, the historians spoke to former residents who can be forgiven for waxing nostalgic about what it was like. Although just a mile or so from where Santa Rosa would claw its way into existence, Franklin Town was still an untamed place. William Franklin’s son told the Press Democrat deer and antelope were then plentiful, and “a few minutes of fishing would suffice to catch a bag full of trout.”

Small though it was, there was also a sense of community. When the Coulters celebrated their golden wedding anniversary in 1904 the PD printed a notice they hoped the event would be also a reunion with their old friends who remembered Franklin Town:

| Fifty years ago on that date in the old Santa Rosa, then known as the town of Franklin, Mr. and Mrs. Coulter were married, and it is hoped that when they celebrate the important occasion the honored pioneers will have the pleasure of having as their guests several of those who were among those present at their wedding day in the old town, in 1854. |

| 1 See “CITY OF ROSES AND SQUATTERS” for more on Santa Rosa’s founding |

| 2 Although there are easier explanations for the name, among his eleven siblings Oliver had an older brother, François Xavier Beaulieu, b. 1805 Quebec, d. 1875 Detroit, who had no known association with California and was not mentioned by Oliver in the Santa Clara mug book profile. Oliver Beaulieu could neither read nor write according to the 1860 census, which might explain why his name was also spelled as Boulieu, Boleau, Boliew, Boulieu and Bolio |

| 3 Gaye LeBaron et. al., Santa Rosa: A Twentieth Century Town, 1985 |

| 4 Kim Diehl, Oliver Beaulieu and the town of Franklin, unpublished, 1999 and 2006 errata |

| 5 Confusing everything further, the city thought it would be a swell idea to rename part of Cemetery Lane to Franklin Avenue in 1893, although it’s nearly a mile away. |

| 6 “Half-Way House” was a common name for a roadhouse at the time. There was another on the road between Santa Rosa and Petaluma, which appears to be the original name for Washoe House between 1859-1861. |

| 7 The timeline in the PD article is confusing because it doesn’t mention his parents separated in the 1860s, with William moving to Santa Rosa and the family going to Glen Ellen. |

| 8 Diehl op. cit. pg. 19 |

| 9 As noted here previously, James P. Clark bought Julio Carrillo’s “stall and buggy shed” and turned it into the Fashion Livery Stable – an operation so big it would take up the entire city block where the Roxy movie theater complex is today. |

| 10 Sterling Coulter’s house was moved again in 1872, this time to lower Fourth Street midpoint Wilson and A streets, where it continued to be used until 1925 and was demolished to make room for a new office building. |

| 11 Charles Justi (1806-1885) was the retired captain of the Georgiana, a Sonoma Creek-San Francisco sidewheeler. For reasons unclear, editors had trouble getting his name right; Half-Way House appears on the 1866 map as “Justin’s Hotel,” and the Democrat newspaper took to calling the vicinity as “Justa Station.” |

Title Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

HISTORIES THE CITY OF SANTA ROSA. HISTORICAL SKETCH.

Origin of the Name – What it Contains and How it is Supported.

…In the year 1852 A. Meacham and Barney Hoen had a store at the old adobe. They sold goods and purchased Spanish cattle for the San Francisco market. F. G. Hahman purchased the interest of Meacham and carried on the business at the old adobe. Mr. Meacham had bought of Julio Carrillo seventy acres of land, on a portion of which Santa Rosa stands. In 1853 Hartman, Hahman and Hoen purchased this tract of 70 acres from Meacham for $1,600, and with Carrillo, laid off the town. The line between them ran through C street and the center of the plaza. The firm donated the east half and Carrillo the west half of the plaza to the town. Meanwhile a few houses were built at the junction of the Sonoma road with the Fulkerson lane. This was called the town of Franklin. S. T. Coulter had a store, and Dr. J. P. Boyce was the architect and builder of one of its redwood houses. In the meantime Santa Rosa was growing. Hahman put up a store here, and slowly but surely Franklin town gravitated from its base to Santa Rosa. Among the buildings which changed location was the old Baptist church on Third street, which was the first, and for a long time, the only church in town.– Sonoma Democrat, January 2 1875

SANTA ROSA–CONDENSED SKETCH OF ITS EARLY HISTORY

In the summer of 1853, the question of the removal of the county seat from the town of Sonoma to a more central locality was agitated. A town was laid off at what was then the junction of the Bodega, Russian river and Sonoma roads, just where the cemetery lane unites with the Sonoma road, near the eastern boundary of the city. Dr. J. F. Boyce and S. G. Clark built and opened a store there. Soon after, J. W. Ball built a tavern and a small store. H. Beaver opened a blacksmith shop, C. C. Morehouse, a wagon shop, W. B. Birch, a saddle-tree factory.In September, 1853, S. T. Coulter and W. H. McClure bought out the business of Boyce and Clark. The same year the Baptist church was built, free for all denominations. Thus early was liberality in religious matters established on the borders of Santa Rosa, and happily it continues down to this day. The only two dwellings were owned by S. T. Coulter and H. Beaver.

Franklin town had now touched the high tide of its prosperity, and was destined to fall before a more promising rival which, up to this time had cut no figure in the possibilities of the future…

– Sonoma Democrat, July 8, 1876

…Early in 1853 J. W. Ball came into the valley; he first located on the Farmer place, on the south side of Santa Rosa Creek. There a number of his family died of small-pox; he then moved over to the Boleau place, where Dr. Simms now lives, and kept there a sort of tavern and store. He bought ten acres of land at the junction of the Russian river, Bodega and Sonoma roads, where the cemetery land now intersects the Sonoma road, and laid off a town there, which was called Franklin-town. S. G. Clark and Dr. Boyce, who had bought out Ball, built and opened a store in Franklin. Ball had a tavern there; H. Beaver a blacksmith shop, and W. B. Birch a saddle-tree factory. In September, 1853, S. T. Coulter and W. H. McClure bought out Boyce & Clark.

The same fall the Baptist church, free to all denominations, was built. For a short time Franklin divided the attention of new comers with Santa Rosa and the “old adobe” [the former Carrillo family home]. The selection of Santa Rosa as the county seat, in the fall of 1854, put an end to rivalry. Within the year following all the houses in Franklin were moved to the new county seat, including the church, which still stands on Third street, between E and D streets. In 1875 it was sold and converted into two tenement houses…

– Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Sonoma County, California by Robert A. Thompson, 1877

…In the Spring of 1853, there arrived in the Santa Rosa valley one John W. Ball, who located on the south side of the Santa Rosa creek, but losing several children here from small-pox, which was epidemic in this year, removed to certain land, about three-fourths of a mile from the present city, the property of Oliver Boleau, a French Canadian, a part of whose house (now in the occupation of Dr. Simms) he rented, at one hundred and fifty dollars per month, and opened a small store and public house. The then direct road from the Russian river, the districts to the north of it, and Bodega country, to Sonoma, at that time the only place of export from the county, met at this point, therefore Boleau conceived the idea of here establishing a town. He had about half a mile square surveyed, and named it Franklin, after a brother in Canada; it was placed at the junction of the Sonoma road with the Fulkerson lane. That Spring, S. G. Clark, Dr. J. F. Boyce and Nute McClure bought out Ball and erected a small dry goods store of split redwoods, in size, twenty-four by thirty-six feet, where they continued business until the Fall, when the firm of Clark, Boyce & McClure was bought out by McCluer and Coulter. In the same season John Ball erected a wooden hotel, there being then in town H. Beaver, who kept a blacksmith shop, and W. B. Birch, a saddle-tree manufacturer, while in the early part of 1854 S. T. Coulter erected a dwelling house.

The selection of Santa Rosa as the capital of the county, put an end to all rivalry which may have existed between Franklin, the old adobe, and it. One by one the buildings erected in Franklin were transferred to Santa Rosa, until in 1855 their entire removal was effected; the first house in that short-lived city being now located on Eighth, between Wilson and Davis streets, occupied by J. T. Campbell, while that erected by Coulter is now the Boston saloon, on Fourth street. A Baptist Church, free to all denominations, which had been there constructed in the Fall of 1853, was also moved, and after serving the purpose for which it was originally built, on Third, between E and D streets, was, in 1875, sold and converted into two tenement houses. This was the first church built in the township and city…

– History of Sonoma County by J. P. Munro-Fraser, 1880

…Mr. Meacham had purchased from Julio Carrillo eighty acres of land, just west of the Bolio [Boleau] tract, it being that portion of the present city [Santa Rosa] lying east of the late Plaza. The firm of Hoen & Co., purchased this tract of Mr. Meacham August 9th, 1853 — “Say 70 1/2 acres, opposite Julio Carrillo’s, for the sum of $1,600.” About this time — the Summer of 1853 — it began to be very evident that there was going to be a town somewhere in the neighborhood of the Santa Rosa House [the old Carrillo adobe]. W. P. Ball, a blacksmith, had a shop and small house on the Bolio place. A town was laid out on the land of Bolio, just where what is known as Cemetery lane intersects the Sonoma road.

This was the point of junction of the Sonoma, Bodega and Russian River roads. It was a good town site one would think, and beautifully located. Dr. J. F. Boyce and S. G. Clark built a store there; Ball built another and an inn; H. Beaver started a blacksmith shop; C. Morehouse a wagon shop, and W. B. Brush a saddle-tree factory. The town took the name of Franklin Town — a good name a town of “free men.” But it did not survive. Why, it is difficult now to say. W. H. McClure and S. T. Coulter, present Master of the State Grange of the State of California, bought out Boyce & Clark. The Baptist Church was built. Mr. Coulter and Mr. Beaver had dwellings in Franklin Town. All this was in the year 1853. When the residents of Franklin Town heard of their having a formidable rival close at hand they smiled at the idea…

…A grand joint celebration and electioneering high-jinks feast was held on the 4th of July, 1854, to show up the new town and to get votes for the proposed new seat…After this Fourth of July celebration Franklin Town collapsed; one by one the houses gravitated to Santa Rosa, some on rollers, some on wheels, some otherwise, but all came. The next Spring the purple lockspur and the yellow cupped poppy contended for supremacy on the site fo the hopeful cross-road village of the previous Spring…

– Central Sonoma: A Brief Description of the Township and Town of Santa Rosa, 1884 (SAME AS Resources of Santa Rosa Valley and the Town of Santa Rosa, Sonoma County, California by R. A. Thompson, 1884)

OUR OWN HOME

ITS PAST PROSPERITY AND PROMISING FUTURE.

…The next house was built just across the creek from the “old adobe”, on what is now the Dalglish place, by Oliver Bolio. David Mallagh, who married one of the Carrillo girls, kept the first store in the oid adobe. In 1852 he sold out to A. Meacham, who is now residing on Mark West creek, an honored and highly respected pioneer citizen. there was a junction of the Russian River, Bodega and Sonoma roads at the corner of Capt. Grosse’s hop yard, just where the cemetery lane comes into the main road. Quite a cluster of houses gathered about the corners. Bolio, who owned the land, laid out a town there which had the name of Franklin. Dr. J. F. Boyce and S. G. Clark had a store there, and W. B. Brush a saddle tree factory. A good saddle tree maker, in those days, had fortune by the forelock…– Sonoma Democrat, January 2 1892

RISE AND FALL OF FRANKLIN TOWN.

While Santa Rosa –floral city of the plain–was in early bud, a near-city was growing up–in the night, as it were. Its forefathers called it Franklin Town. Why “Town” and with a big T, has never been told. Only a few of the old guard yet this side of the cemetery gates really remember Franklin Town. As it came, it passed away in the night, or rather, in the morning of its first-day-after.Its site is just without the present city line on the east, near the reservoir hill. Some day, perhaps, the extension of the boundaries will take in the old place, and then Franklin Town will awake to life–becoming an addition to the Santa Rosa it sought to blight in tender flower. Chiefs of the city in embryo were Dr. J. F. Boyce–venerable “Doc Boyce” who medicined and surgeoned the later Santa Rosans for many a year and eccentric to the point of profanity, which often drove his patients to recover quickly and get him out of the sickroom; also S. T. Coulter — good old “Squire Coulter,” Pioneer Patron of Husbandry, Lord of the Sonoma Grange, and who didn’t believe that the grass and herbs and the trees that bore fruit in their season were first sprouted on the Third Day of Creation, and said even Luther Burbank couldn’t grow things that speedy. Now, deep under the turf these “old forefathers of the hamlet sleep,” and heaven speed their run to the saints.

One feature that shines like a star through this dark Tale of a Lost City, is Franklin Town had a church, then the only church in the county except the Mission Solano at Sonoma. Its faith was Baptist, though all shades of the “two and seventy jarring sects,” as Omar Khayyam phrases them, were welcomed to use that sanctuary for the uplift of any possible sinful citizen of Franklin Town. The willow-bank creek consecrated by Parson Juan Amoroso when he baptized the Indian girl and called her La Rosa — spiritual daughter of Santa Rosa de Lima — splashed and bubbled pure as the Jordan when John came preaching in the wilderness, but it is not positively known that Doc Boyce or Squire Coulter ever availed themselves of the lustral waters flowing by Franklin Town, unless to wash a shirt.

But the finger of doom was writing on the clap-board walls of Franklin Town, Hoen, Hahmann and Hartman — the triple H-builders of Santa Rosa, were housing up C — now Main — street. The diplomatic dads of the coming place got up a Welcome-To-Our-City barbecue, and when the Franklinites saw the hosts of all-invited guests gathering around the Santa Rosa flesh-pots, they also saw the finish of Franklin Town. Soon it was in transit, the Baptist church, on four wheels, led the way like the Ark of the Covenant before the immigrant Israelites herding to the Promised Land, and it afterwards was the pioneer tabernacle, upholding the doctrine of close-communion and total immersion in Santa Rosa, and fitting the aging citizens for another immigration — into Eternity.

– History of Sonoma California by Tom Gregory, 1911:

WILLIAM FRANKLIN AND HALF-WAY HOUSE HALF WAY HOUSE For Sale.

THE subscriber wishing to leave the State, offers his place, known as the Half Way House between Santa Rosa and Sonoma, for sale. The House is too well known, and too long established to need any recommendation. Apply on the premises, to WILLIAM F. FRANKLIN.– Sonoma Democrat June 17 1858

Half-Way House For Sale

THE SUBSCRIBER, wishing to leave the State, offers for sale his place, known as the “HALF-WAY HOUSE,” between Santa Rosa and Sonoma. The House has been eight years established, and is too well known to need any recommendation. For particulars, apply premises. W. F. FRANKLIN, Prop’r– Sonoma Democrat July 21 1859

Fire. —The stable of the Half-way house, W. F. Franklin, proprietor, situated on the road leading from Santa Rosa to Sonoma, was destroyed by fire on Sunday night at eleven o’clock, together with its contents, which consisted of two stage horses belonging to Linihen & Co., proprietors of the Healdsburg and Sonoma line of stages, a horse belonging to a peddler, a quantity of hay and a horse belonging to Mr. Franklin. Through the greatest exertions the hotel was prevented from taking fire. The loss is not less than $1,000. The fire is supposed to be the work of an incendiary.

– Sonoma Democrat, August 8 1861

FOR SALE. FRANKLIN’S HALF-WAY HOUSE!

Situated on the Road from Santa Rosa to Sonoma.

The place is so well known that a lengthy description is deemed unnecessary.

As urgent business calls me to England, I am obliged indispose of my property, and will sell the above place

VERY CHEAP FOR CASH!

W F. FRANKLIN.

All persons indebted to me by note or book account will save expense by settling on or before the 1st December next. W. F. FRANKLIN.– Sonoma Democrat, October 17 1861

Many of our readers no doubt have observed when passing over the road to Sonoma, from this place, when near the Half-way House, a range of hills lying to the East, and bordering along the Guilicos Rancho, which, with their reddish soil and barren surface do not present a fertile aspect. Well, on these apparently barren hills are to be found a number of enterprising German wine growers, who are busily engaged in cultivating the grape…

– Sonoma Democrat, March 21 1863

Half-Way House. —W. F. Franklin, on the Sonoma Road, keeps a good country hotel. We speak from experience, when we say that Mrs. Franklin, the obliging landlady of that establishment, can prepare as good a meal for the weary traveler, in as short a time, as could be desired by any one.

– Sonoma Democrat, June 10 1865

Against W. F. Franklin and improvements on land bounded Krom [sic: Crone, Kron or Krone] and Williams, east by Napa mountain, south by Warfield, and west by Justi, Sonoma county, California, for taxes $8.18 and costs of suit $16.50.

– Sonoma Democrat legal notice, August 22 1868

Last Sunday, in company with a few friends, we paid a flying visit to the new silver mines on Sonoma mountain. Taking the Sonoma road from Santa Rosa, we drove through the Guilicos Valley to the Half-way House, kept by our old friend Captain Justa…

– Sonoma Democrat, April 10 1869

…[Charles Justi] was captain of the steamer Georgiana, running between San Francisco and Embarcadero in the early fifties, whence he obtained the title Captain. He bought and owned 500 acres of land near Glen Ellen but lost all but 40 acres through litigation and defective titles. For many years the Captain [Justi] and his estimable wife conducted the Half-way house at the old homestead near Glen Ellen, and before the advent of railroads, while the stages were still running to Santa Rosa, did a thriving business.

– Sonoma Valley Expositor, June 9 1899

VISITOR HERE RECALLS DAYS 70 YEARS AGO

Pioneer Tells of Time When Santa Rosa Was Known as Franklin

The earliest history of Santa Rosa, when the village was called Franklin Town, was recalled here yesterday by the visit of William Franklin. Jr., of San Francisco, son of the pioneer after which the first settlement was named.William Franklin and his wife came to Santa Rosa from Australia in 1852, after having been shipwrecked on the Hawaiian Islands, when his sailing vessel stopped there to secure water. A year was spent in the islands before another vessel could be secured to complete the voyage to California, and during this year the child who came here yesterday, a man of 73, was born.

The elder Franklin settled on the Sonoma-Santa Rosa road, just east of the present city, and with the arrival of others the village of Franklin Town came into being. The subsequent settlement and growth of Santa Rosa finally did away with the old village. Franklin worked for William Hood in his flour mill, first in Rincon Valley, and later in Franklin Town; built one of the first wooden houses in the city on what is now upper Fourth street; and helped build the old Colgan hotel on First street.

The Franklin family later moved to Glen Ellen, residing in the Dunbar district, where William Franklin. Jr., attended school with Nicholas Dunbar, father of Charles O. Dunbar, present mayor of Santa Rosa. John Dunbar, uncle of the mayor, now of San Luis Obispo, and Franklin are the only survivors of the class which Franklin attended, as far as he knows, he said yesterday.

Children of the Dunbar, Box, Justi and Simons families were in the class, as was the late George Guerne and his wife, Eliza Gibson.

Franklin bemoaned the condition of Santa Rosa creek, where, he said, splendid fishing conditions have been destroyed by the dumping of sawdust, tan bark and other debris. In his day, Franklin said, a few minutes of fishing would suffice to catch a bag full of trout. Grizzly bear were then plentiful within a few miles of the city, and deer, antelope and other game could be secured with little difficulty. he said.

– Press Democrat, July 21 1925

PROPERTIES Another new building of brick will be commenced immediately, weather permitting, by Messrs. Melville Johnson and Jackson Temple, for a law office. It will occupy the site of the old Coulter House, next door south of the bank. This old landmark which long years ago voyaged from Franklin Town to this place, will be removed to a quiet locality more suited to its age and long services. The new building will be 18 feet front by sixty feet deep, one story, divided into three large offices.

– Sonoma Democrat, December 14 1872

Sale of Noted Farm. – The Lucas farm, near Santa Rosa, containing four hundred acres, has been subdivided and sold during this month by Dr. J. R. Sims, acting as agent for the owner. The subdivision nearest the town — within half a mile of the corporation limits containing forty-eight and one-half acres, was purchased by James Seawell, of this place, and Dr. Rupe, of Healdsburg, for $160 per acre. This left two hundred acres of bottom land, fronting on the Sonoma and Cemetery roads, and one hundred acres on the ridge back of the farm. This was sold out in six plats, to suit purchasers, each one taking a strip of hill land as wide as their frontage on the bottom. Richard Fulkerson purchased eighty-two acres, Including the land which lies north and back of the cemetery. Next, Frank Straney bought fifty-nine acres — thirty-two of bottom land. Next, L. B. Murdock, forty-five acres — forty of bottom land. Two parties from Yolo took the next one hundred acres. Dr. Simms purchases the home place, with the rest of the land, between thirty and forty acres in the bottom. The whole tract will net $41,500, which is the largest and best sale of land ever made in the vicinity of Santa Rosa. The Lucas farm was the first settled in this vicinity. On it was the site of the once rival of Santa Rosa, the town of Franklin.

– Sonoma Democrat, December 27 1873

HISTORIC LOCAL BUILDING RAZED – One of the first store buildings to be erected in Santa Rosa, or rather in old Franklin Town, was razed last week on lower Fourth street to prepare for the new Rosenberg building. Few people realized that the little wooden structure had such a history. It was the building in which the late Squire Coulter ran a store in Franklin Town in the ’50s. Later, when Santa Rosa was founded, it was moved to where the Hahman drug store now stands in Exchange avenue, where Squire Coulter occupied it as his business house. Later it was sold and was again moved to lower Fourth street, where for nearly 70 years it has been occupied by various businesses.

– Press Democrat, July 26 1925

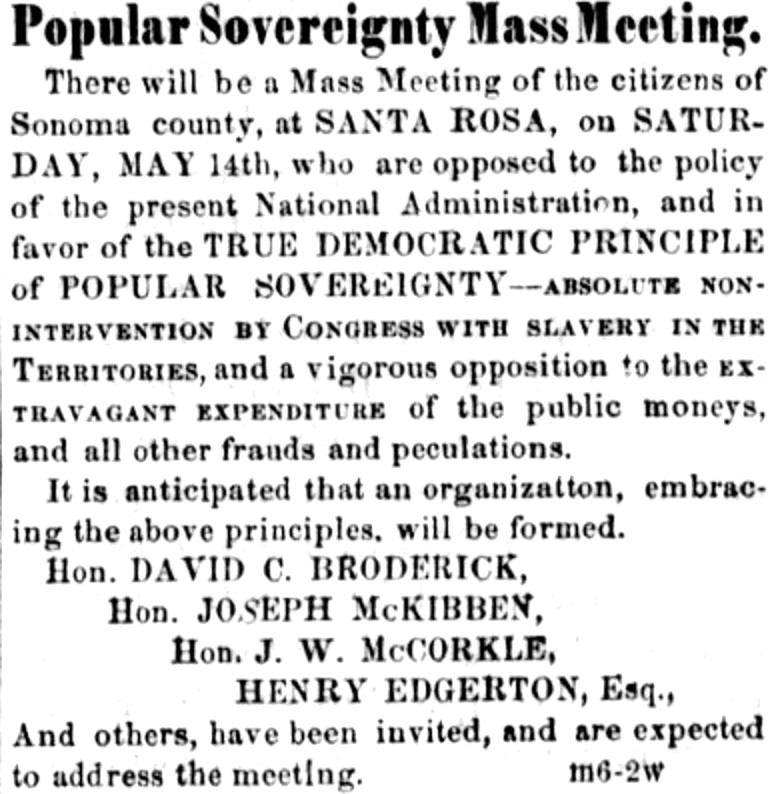

MISC Sonoma County Democratic Convention. At a meeting of the democratic delegates of Sonoma county, held at Franklin, Santa Rosa Valley, on the 8th inst., Wm. Ross was elected President.

– The Placer Herald, July 15, 1854

THE BAPTIST GOLDEN JUBILEE …In 1856 the primitive little church building was moved from Franklin to the Santa Rosa that was springing into existence. It was put on wheels and hauled there by six yoke of oxen. On Third street the oxen halted and the church occupied a site west of where the People’s Church now stands.

– Press Democrat, March 21 1902

The distinction of living to celebrate their golden wedding falls to the lot of comparatively few married couples. But when it comes to being married fifty years and living the half century of married life in the same community makes the distinction very unique. If both are spared to see February 21 come round such a novelty will be enjoyed by Mr. and Mrs. Sterling Taylor Coulter of Santa Rosa. Fifty years ago on that date in the old Santa Rosa, then known as the town of Franklin, Mr. and Mrs. Coulter were married, and it is hoped that when they celebrate the important occasion the honored pioneers will have the pleasure of having as their guests several of those who were among those present at their wedding day in the old town, in 1854.

– Press Democrat, February 12 1904