Imagine finding a treasure trove which you didn’t even know existed – yet there they were stacked on the library table, a dozen high quality images of the 1906 Santa Rosa earthquake, all photographed in 3D.

Those who follow me on Facebook @OldSantaRosa know I’ve been recently upgrading images related to the disaster. Sometimes I take my portable scanner to the Sonoma County Library History & Genealogy Centre and rescan some of the collection’s glossy 8×10 prints at a high resolution, followed by using a Photoshop-like application to slightly enhance brightness/contrast levels as necessary. But some photos are still too dark, too low-res, or have other problems that make it hard to coax out a workable image; that was the case of a few photographs which were the only known pictures taken on the actual day of the earthquake. All of them shared an unusual feature – an arched top, which is sometimes found on stereograph cards. Did this mean there was a photographer in Santa Rosa taking 3D pictures while the crisis was underway?

(RIGHT: Stereoscope ad from 1902 Sears catalog)

(RIGHT: Stereoscope ad from 1902 Sears catalog)

In the decades around the turn of the last century, probably every middle class home had a stereoscope with an assortment of cards; passing the viewer around was a popular divertissement to while away the hours and to entertain guests in the parlor. The number of stereo views available was seemingly endless – Civil War battlegrounds, world fairs, picturesque scenery, historic events (including the aftermath of natural disasters), exotic places and whatnot. There were also racist views glorifying Antebellum slavery and porn.

Rarely, however, are 3D family snapshots found – the stereoscopes and cards might have been ubiquitous, but stereo cameras were not. They could cost 10x more than a very good quality regular camera (the equivalent to about $1,500 today), used twice as much film, were bulky and each shot needed to be composed with care. While Kodak made low-end stereo cameras for amateur use they were limited to fixed focus and shutter speeds and did not sell very well.

When I asked Sonoma County Archivist Katherine Rinehart if the library had any information about those arched top images, she said they were copied from stereoscopic cards – which were in the library’s collection. Would I like to see the originals?

Be still me quaking jibbers, I could not believe what I found. Not only are the cards in near-mint condition after 110+ years, but the images have none of the problems found in the copies which required enhancement. The photos are bright, in focus and could have been taken yesterday. And because we can now see both parts of the stereo pairs, new details appear – including additional people – at the far sides of the images.

That there are even twelve stereograph cards of the 1906 Santa Rosa earthquake is nothing short of remarkable, as there are not very many 3D quake-related pictures available from 1906 San Francisco; there are over 3,000 regular photographs but the only stereographs I can find are the 163 colorized views at Bancroft Library and 97 at the Library of Congress. (I suspect there are duplicates between the collections, but have not compared them.)

So who was it that captured Santa Rosa’s worst day in 3D? Written on the back of the cards is “Roberts Sebastopol,” except for one that has “HRoberts.” That would be Henry Edmund Roberts, who had a photography studio on Sebastopol’s Main street for only a few years, probably 1905-1909. He didn’t leave much of an impression around here; as far as I can tell he never advertised. By 1914 he was the resident photographer at General Grant National Park (now Kings Canyon National Park) selling views of the great sequoias to tourists. In 2002 the Visalia Times-Delta published an appreciation written by a famed naturalist about the historic importance of his work, and there’s now a Henry E. Roberts Collection at the park museum in Three Rivers with hundreds of his photographs. And yes, he continued to create stereographs, including one which is presumably (judging by its caption) a self portrait of Henry and his son Edmund peering into the vales of the High Sierra.

So who was it that captured Santa Rosa’s worst day in 3D? Written on the back of the cards is “Roberts Sebastopol,” except for one that has “HRoberts.” That would be Henry Edmund Roberts, who had a photography studio on Sebastopol’s Main street for only a few years, probably 1905-1909. He didn’t leave much of an impression around here; as far as I can tell he never advertised. By 1914 he was the resident photographer at General Grant National Park (now Kings Canyon National Park) selling views of the great sequoias to tourists. In 2002 the Visalia Times-Delta published an appreciation written by a famed naturalist about the historic importance of his work, and there’s now a Henry E. Roberts Collection at the park museum in Three Rivers with hundreds of his photographs. And yes, he continued to create stereographs, including one which is presumably (judging by its caption) a self portrait of Henry and his son Edmund peering into the vales of the High Sierra.

There are three ways to view these images.

The easiest is to use 3D glasses with red/blue lenses (actually, red/cyan) to look at the anaglyphs below. You could have a pair of these cardboard and cellophane glasses lying around at home or work even if you don’t know it; they’re provided with some video games, DVDs, comic books as well as sometimes in science textbooks and journals. If you still come up empty ask the (grand)kids or buy them online – I can find no store in Santa Rosa that carries them, sorry. (Tip: Don’t believe websites claiming you can MacGyver these glasses by using red and blue colored plastic film from an art supply store. The plastic isn’t clear enough and to get any effect at all and the film must be doubled over, which makes the red side too dark. Instant headache.)

The easiest is to use 3D glasses with red/blue lenses (actually, red/cyan) to look at the anaglyphs below. You could have a pair of these cardboard and cellophane glasses lying around at home or work even if you don’t know it; they’re provided with some video games, DVDs, comic books as well as sometimes in science textbooks and journals. If you still come up empty ask the (grand)kids or buy them online – I can find no store in Santa Rosa that carries them, sorry. (Tip: Don’t believe websites claiming you can MacGyver these glasses by using red and blue colored plastic film from an art supply store. The plastic isn’t clear enough and to get any effect at all and the film must be doubled over, which makes the red side too dark. Instant headache.)

Converting the originals to anaglyphs had mixed results, despite eye-crossing hours spent wrangling the overall effect to be as good as possible. All images have some color fringing – usual on all anaglyphs – but this set has unusually difficult problems because some images have objects both very close to the viewer as well as in the middle and far distance. The anaglyph technique does not work well with such a wide depth of field, so I was required to composite several of these from up to six separations. I could spend another week tweaking them further…but sorry, no. This will have to do, particularly since there are other ways to view the photos in 3D without these drawbacks.

The second method is my preferred technique and uses no special equipment at all – just our naked eyes. Nearly everyone can form a 3D image via our natural ability of stereopsis. I say that with confidence because I can do it even though I’m extremely nearsighted, with one eye needing a corrective lens twice as strong as the other. My wife, Candice, coached me on how to do it and after a few minutes of practice, my first stereograph popped into 3D. I was so amazed I began to giggle – and trust me, the sound of an old man giggling is a yet untapped sound effect that will someday instill a sense of unspeakable dread in horror movie fans.

The trick is to let your eyes completely relax, as if you were looking in the distance. Your nose must be aligned with the separation line between the two images, so each pupil is looking directly at the image on that side.

Smaller images are better, particularly while training your eyes for the first time and trying to find the distance that works best with your vision. All of the stereographs shown below render in 3D for me when viewed on a tablet or cellphone, as long as the stereograph card is displayed no wider than about four inches. I hold the tablet/phone up to ensure it’s straight ahead and about six inches from my face. (Your optimal distance will probably be closer to a foot, and those who are farsighted might need to use reading glasses.)

Before looking at a stereograph, I always find it helpful to get the display into position and begin by gazing at something at the far side of the room, then keeping my eyes fixed, turning my head towards the image. Try to imagine looking through the display. If you don’t get the 3D effect immediately don’t try to force it into focus – repeat this exercise until it works. After you’ve experienced the technique a few times it gets easier.

Practice using the stereograph card below. This is one of the best examples I’ve found – there are at least ten distinct depth planes. The beauty of this technique is that once your eyes are “locked in,” you can study every aspect the photograph in great detail.

“On duty ‘amid the encircling gloom’ of a city’s certain destruction. Magnificent fire scene near Union Ferry Bldg. San Francisco.” Courtesy Library of Congress

“On duty ‘amid the encircling gloom’ of a city’s certain destruction. Magnificent fire scene near Union Ferry Bldg. San Francisco.” Courtesy Library of Congress

Method #3 is to build yourself a stereoscope and print out the cards. A stereoscope makes the stereopsis technique easier by placing a separator between the images so you can’t look at the image for the opposite eye; the device also helps by using lenses with a focal length of 200-300mm, which is the distance between the eyepiece and the card. Several plans are available by searching “how to make a stereoscope” with levels of difficulty ranging from incorporating the prismatic lenses used in the original devices (which force you to be slightly wall-eyed) to taping cheap reading glass lenses on the end of a cardboard shoebox. The plans at “Fun Science Gallery” seem the most practical to me, but I have not tried building any of them.

The site above also includes directions for making a mirror stereoscope, which can display large, very high resolution stereo pairs. These are typically scientific devices used by geologists and cartographers but a tabletop model also could be made with four mirrors. If you build one of these, let me know!

(All of the Santa Rosa stereographs are courtesy of the Sonoma County Library and are resized to a 9cm width with enhanced contrast and brightness for better stereopsis. Click or tap on any of those images to view the untouched original card at full resolution.)

“Burning of the Tupper House”. (This caption may be incorrect, as there was no Tupper family listed in the city directories for either 1905 or 1908. This photo was taken from the marble and granite works on the corner of Fourth and Davis, looking west.)

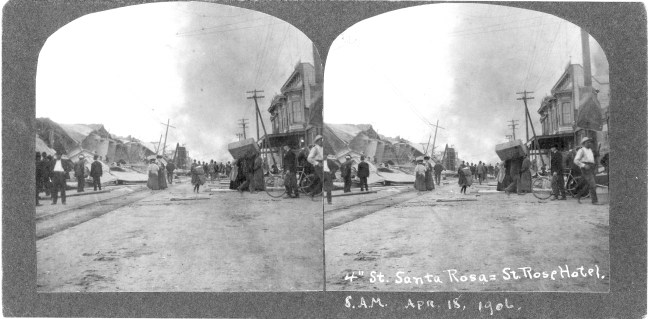

“4th St. Santa Rosa – St. Rose Hotel. 8 A.M. Apr. 18 1906.”

“Looking east to Court House. South side of 4th St.” (This is the rubble from the massive explosion of the Haven Hardware store, which entirely demolished the south side of 4th between A and B streets. A panoramic view of the scene is available here.)

“S.R. Loan & Trust Co’s Building. 4th St. Court House in distance.”

“4th St. looking west from Court House”

“‘B’ St. Santa Rosa – Looking for the dead 7:30 A.M.”

“Scene on 4th St. morning of the fire.”

“Purrington’s residence” (Joseph Purrington’s address was 620 Mendocino street)