Sebastopol has admirable things in its past as well as the awful, but goddesses help me, the cliché is true: Go back to the earliest years and the town was always quirky. Current Google results on “Sebastopol” and “quirky” – about 95,200.

The town deserves plaudits for being a tolerant and (mostly) welcoming place for ethnic minorities that were hated and persecuted elsewhere in Sonoma county during the 19th century. A Native community endured continuously on the banks of the Laguna through the early 1900s, complete with their own cemetery. The following article shows Sebastopol had a thriving Chinatown going back to 1869, even as Chinese immigrants were elsewhere being driven out of the area. Later Japanese newcomers also found it a good place to bring their families and put down roots.

On the flip side, lots of awful stuff happened in the early 20th century, particularly the child labor camps where boys as young as seven were brought up here from the Bay Area to work in the fields and canneries. Feel free to also rage over the destruction of Lake Jonive, an irreplaceable treasure which the town turned into an open cesspool and garbage dump.

But there was often something different about the people who lived there. They seemed to be the sort that liked to doodle in the margins of a cookbook more than following the recipes – and I measure that by the number of times I’ve read something about the village in the old newspapers and found myself mumbling, “wow, that’s unusual.” What they often did was just…quirky.

|

|

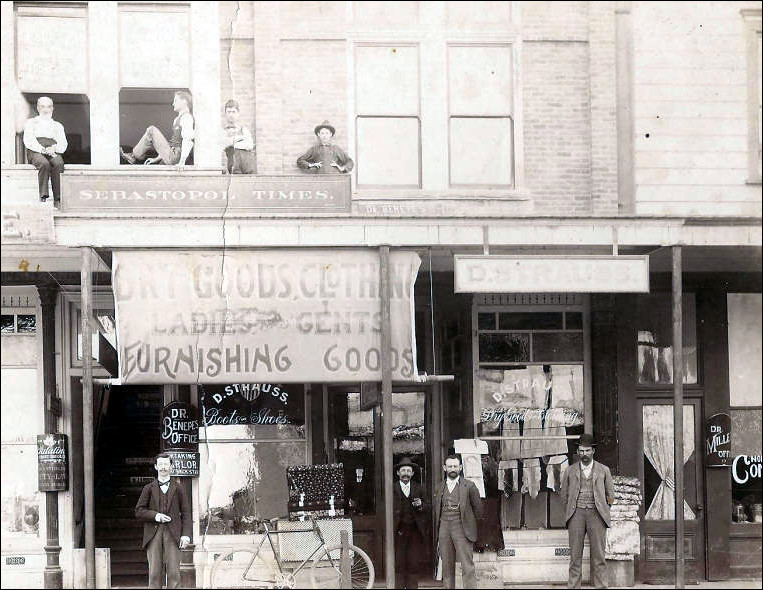

Downtown Sebastopol in 1881 (Western Sonoma County Historical Society Collection)

|

They certainly did not take themselves as seriously as some folks during the Civil War. Sebastopol sided with the Confederacy, as did the rest of Sonoma county (except Petaluma) but unlike the clench-jawed fanatics over in Santa Rosa who actually rooted for the North to be crushed, the Southern sympathizers of Sebastopol mostly enjoyed punking the mainstream “Union Democrat Party” – the so-called moderates who wanted peace declared and everything to go back as it was before Secession.

In 1862, with their customary pre-election barbecue and party rally coming up, the Democrats of the Analy District hosted speeches by candidates. One who appeared was a San Francisco politico named Worthington who was apparently obscenely heckled or otherwise deeply insulted by some Sebastopol wiseguy. Whatever was said must have been pretty ripe because the candidate exploded at the audience of voters:

“…[Mr. Worthington] was suddenly brought to a close upon that topic, however, by a remark from some one in the crowd at which he seemed to take umbrage, and closed in a terrific abuse of the citizens of Sebastopol — stating that if he came there to the barbecue, he would take good care to bring his dinner with him.”

The following year the Analy Democratic Club announced they were throwing another party barbecue, and all Democrats in the county were invited. (It turned out to be a very big deal indeed, with speakers speechifying from 10AM until midnight.) Right after it was announced, the Sebastopol pranksters erected a flagpole taller than anything else around, waving a Union flag and a streamer with the upside down word, “Constitution.” The point, I’m guessing, was for them to hang out at the base of the flagpole and mockingly pretend to be namby-pamby Union Democrat moderates.

“They had a grand ‘pow-wow,’ and apparently had a good time generally,” commented the (pro-Union) Petaluma Argus. “The whole affair was evidently got up for the purpose of ‘roping in’ outsiders; but we hope with no effect. The whole affair is so transparent that nobody but very silly people can be deceived.”

The Argus also heard from a Sebastopol subscriber complaining that his newspaper was being stolen by the very people who looked down on its anti-Confederate content as the equivalent of “fake news,” yet were still reading the paper avidly. “This is just like the rebels here. They sneak around get the reading of the paper and then talk all week of the march of vile abolition ideas.”

At least once, though, the joke was on Sebastopol’s anti-Yankee fanboys. During the Civil War, Fort Alcatraz was used as a military prison for Confederate sympathizers charged with seditious acts, and a telegram arrived that “Dr. Harris, Willson and Valentine, three noted rebels of Sebastopol, had been arrested for treason and would be sent to Alcatraz.” Hours later it turned out to be a hoax, and much celebratory drinking followed. What’s interesting about this anecdote, however, is that it seems like a “dog that didn’t bark in the night” story. If some truly innocent men were sent to the slammer for the duration of the war you’d expect an angry outcry from friends and neighbors; here, the attitude seems to have been, “well, we all knew they’d get arrested eventually…”

The final Civil War episode concerns farmer Aaron Barnes, who definitely took his politics seriously. In 1863 a man named Peters came to his farm to buy a wagonload of fruit. A deal was made and Peters was invited to stay the night, as it was getting late. Late that evening – and presumably after a bottle or three had been uncorked – the conversation turned to one of the big controversies of the day: The Vallandigham affair.

Clement Vallandigham was an Ohio politician who was exiled to the Confederate states a few months earlier after rabble-rousing against “King Lincoln” and the government. (Obl. Believe-it-or-Not! factoid: He died in 1871 while defending a man accused of murder, arguing that the victim had killed himself by mishandling a gun. Vallandigham was demonstrating his theory in the courtroom when he accidentally shot himself.) When Peters said he had no sympathy for Vallandigham, farmer Barnes “told him no abolitionist should stay in his house, and that he must leave; which he had to do, team and all, but without the fruit.”

|

| Main Street circa 1898 |

That Aaron Barnes anecdote has weight because so little is known about him except basic genealogy (1816-1897). Yet as discussed in the next article, Sebastopol’s Chinatown mainly owed its existence to him – and what happened during a period of great upheaval in his personal life also became one of the most gossip-worthy tales in the history of the county.

In June of 1885, Aaron’s wife Lydia/Liddy died; he was 69 years old at the time, and within five weeks he was married again, his new wife Jessie being younger than all but one of his children.

“The old gentleman concluded that the term ‘single blessedness’ was a misnomer, and a short time since commenced looking about him for another partner,” the Healdsburg newspaper explained. “He met a musical gentleman named Professor Parks, to whom he proffered $500 in consideration of his finding him a suitable wife. The Professor readily accepted, and in a short time a lady from the East, twenty-seven years of age, attractive and cultured, agreed to share the old man’s wealth.” (Sam Parks was the leader of dance and concert bands around Santa Rosa for about thirty years; a “Jessie Burk” which might be her was arrested several times for prostitution/disorderly conduct in Louisville, Kentucky during preceding years.)

A different paper noted, perhaps tongue in cheek, that after their wedding “the young couple left the following day for Lake county to spend the honeymoon.”

Aaron gave his new bride $14,300 in bank stock when they married, followed by local real estate in 1885, 1887 and 1889. Then in 1892 she deserted him.

Aaron gave his new bride $14,300 in bank stock when they married, followed by local real estate in 1885, 1887 and 1889. Then in 1892 she deserted him.

He sued her for breach of contract and sought $20,000 in damages, arguing “…she was not a worthy woman at the time of the marriage, and that it was a scheme on her part to obtain possession of his property.” Jessie Burk Barnes freely admitted she had left him, but insisted she had fulfilled the contract by marrying a man old enough to be her grandpa. The court agreed with her.

The case went to the state Supreme Court in 1895 and Aaron lost again. The court ruled, “When a man marries a woman knowing her to be not virtuous, he forfeits his right to allege that fact as an avenue of escape from the ties with which he has bound himself, and it is presumed that when taking a wife a man will satisfy himself as to her character before leading her to the altar.”

Yet that’s still not the end to the story of Barnes’ family eccentricities. Aaron died a few months after losing the suit, and it was discovered that he placed an unusual clause in his will requiring his estate to be left untouched for twenty years, after which his children – some of whom would have been over 70 by then – could divide it up. This was such a bizarre demand I can’t help but wonder if it was intended as an attempt to protect “his” Chinatown post-mortem. The court declared the long waiting period invalid.

There was still the problem that one of his children could not be found. Samuel – the only kid younger than his ex-stepmom – had disappeared while his dad was still married to her. Since Aaron died, Samuel’s share of the estate was held in trust while the family had him declared legally dead in 1901. But just as his sizable inheritance was about to be distributed to his brothers and sisters, he popped up and contacted them for the first time in twelve years. All were happy he was still alive – let’s generously just presume.

|

| Sebastopol in 1895 (Western Sonoma County Historical Society Collection) |

More stories about Sebastopol during the 1890s come from an obscure memoir, “The Tenderfoot Comes West” by Roy McLaughlin, who spent his teen years there.

McLaughlin sketched what the village was like: “What struck me was the dust and cobwebs everywhere…All the streets were merely continuations of the several intersecting dusty roads.” He wrote there were three general stores complete with “a few men [who] sat around the stove and cracker barrel and exchanged news and gossip,” one full-time church, seven saloons (!) and a large winery. In the little schoolhouse seventh and eighth grade were taught together, and “…the front rows of seats were smaller than those in the rear, which were occupied by boys who were almost grown men.”

There wasn’t much for a kid to do; they swam in the Laguna, which at the time was teeming with carp that were introduced by accident after heavy rains caused a couple of commercial fish ponds to overflow. (One of those ponds was owned by… wait for it… Aaron Barnes.) Boys hung around Chinatown – McLaughlin seemed awfully well-versed in the details of opium smoking – but they also tormented the Chinese men cruelly, as described in the next article. Most exciting was the time “…a troupe that accompanied a horse-drawn merry-go-round spent one winter month with us. They were all ham actors, but their performances in the town hall at least served to relieve the tedium during the season when no work could be obtained in harvesting fruit.”

The key Sebastopol story in his book, though, was a description of one of the town’s quirky drunks:

| There were, of course, many fine, respectable people who quietly went about their affairs. But quite in contrast were the drunkards. I have never seen so many sots of different types as were always in view. Some only occasionally got tight; others were periodic performers, and we knew about when to expect to see them on Main Street. One was of such fixed habits that he deserves special mention. This was old Doc Whitson. One could almost set a clock by his two daily appearances. Early in the forenoon he would walk up the street to the winery, and later in the afternoon would weave his course back down the street, always in an angry mood. On one side of Main Street there was an open ditch, dry in the summer and a gushing torrent in winter. The ditch at one place was crossed by a footbridge consisting of a single board. One winter night during a drenching rain our neighbor heard shouts, and the lady of the house said to her husband, a mild-mannered man, “Will, somebody is shouting. You better see what the trouble is.” Will lighted a lantern and went out toward the noise. Near the footbridge he saw old Doc sitting up to his arms in the water. Will politely inquired, “What are you doing, Doc?” The muffled reply was, “The inquisitiveness of a small village is appalling!” |

|

|

Sebastopol in December 1904 (Western Sonoma County Historical Society Collection)

|

Finally, no discussion of the town’s quirkiness is complete without considering how it got its name. It was originally called “Pine Grove” in 1855, as can be verified in a Sonoma County Journal ad from that December.

Trigger alert: Things are about to become very confusing.

Trouble was, there were lots of other Pine Groves in the state, and the one in Amador County got the official nod from the post office in 1856. That same year the USPS also designated “Sebastopol” as the mailing address for a place – in Napa county.

What we were calling Pine Grove here was officially the post office named “Bodega” and it handled every piece of mail between there and the Oregon border. Then in 1857, the residents of Pine Grove decided it would be really cool if the village were now called Sebastopol instead.

The mess was not sorted out until 1868, and presumably not before a whole bunch of letters were returned to confused senders. That year the post office at the place everyone called “Bodega” was designated Bodega, Sebastopol/Napa was officially renamed Yountville, and Sebastopol/Quirky became recognized as Sebastopol, California. All the many other Sebastopols in Tulare, Sacramento and Nevada counties (“Sebastopol” was obviously a very popular name in the 1850s and 1860s) were left to dream up a different ру́сский name.

But why was “Sebastopol” a popular name at all? The indefatigable John Cummings wrote a research paper on the historical military standoff and how it was celebrated in the Bay Area, while the oldest account of why the name was chosen here appeared in Robert Thompson’s 1877 Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Sonoma County, California:

| …The formidable name of Sebastopol originated in this way: a man named Jeff Stevens and a man named Hibbs had a fight; Hibbs made a quick retreat to Dougherty’s store; Stevens in pursuit. Dougherty stopped Stevens, and forbid him to come on his (Dougherty’s) premises. The Crimean war was raging at that time, and the allies were besieging Sebastopol, which it was thought they would not take. The Pine Grove boys, who were always keen to see a fight–chagrined at the result,–cried out that Dougherty’s store was Hibbs’ Sebastopol. The affair was much talked about, and from this incident the town took its name. |

It’s a fun story, but I can’t find any evidence it is true. There were no men with those names found in the 1850 or 1860 census; that “much talked about” fight wasn’t talked about even in passing within any surviving newspapers of the time (at least, currently available online). Methinks author Thompson was probably repeating some retrofitted barroom tale made up in the twenty years since.

Now that story has been accepted without question, even while more details have been larded onto its ribs. Tom Gregory – author of the county’s 1911 history book and a man who could lie like a salesman working on 50% commission – added that Hibbs’ first name was “Pete” and they were slugging away at each other because they were both so, so passionate about the Crimean War which was already over. Gregory’s account further dripped with gooey prose, “…so out from the red flames of the Crimea, out from the bloody rifle-pits of the Redan, out from the fadeless glory of the Light Brigade, and out from the historical scrimmage at Dougherty’s came out Sebastopol. Jefferson and Peter are aslumber on Gold Ridge, mingling their dust with the rich yellow soil, with orchards to the right of them, vine-rows on the left of them, blooming and fruiting.” Lordy, I do so appreciate reference books that are concise.

A letter from a Sebastopudlian published by the Argus in 1865 also didn’t mention the fight, but simply that they chose to adopt the name of “Russia’s renowned Fortress” – in other words, because it was considered a very honorable name. I agree with Cummings that is the most likely answer, as the writer was probably living there around the time.

Cummings is a fellow newsprint spelunker and a first-rate researcher; SSU offers fifteen of his research papers online, and they have proven invaluable to me. But in this case he was incorrect on several points, particularly, “Pine Grove was renamed Sebastopol in the about seven month period between November 1855 and the end of May of 1856.” Since his essay was finished in 2009, an enormous number of historic newspaper pages have come online and are searchable, providing tools he did not have.

The ads published in the Sonoma County Journal show the name change happened in May, 1857 – although there are still no articles to be found about the switch. After May 22 it’s always Sebastopol in advertisements, except for an old display advert from a non-local delivery company that continued listing Pine Grove as late as 1860.

Sebastopol is the only community around here with a colorful story about its name, and personally I love the idea that some joker in Sebastopol may have made it up, most likely to make the place seem less respectable. From that quirky seed grew a tree that looks mostly like others in the forest until you take a closer look – and then you realize it’s really not quite the same. Not the same at all, and that’s something nice to appreciate.

|

| Sonoma County Journal ads: May 8, 1857 / May 22, 1857 |

…[Mr. Worthington] was suddenly brought to a close upon that topic, however, by a remark from some one in the crowd at which he seemed to take umbrage, and closed in a terrific abuse of the citizens of Sebastopol — stating that if he came there to the barbecue, he would take good care to bring his dinner with him. He then thanked those who had given him their attention, and took his departure, feeling pretty well satisfied, we expect, that Sebastopol was not a very good place for an itinerant political preacher to stop at.

– Sonoma Democrat, August 28 1862

SECESSION IN SEBASTOPOL. — Last Saturday the Democratic party, which now spells its name “Secesh,” erected a pole 91 feet high, and hoisted the Union flag upon it, surmounted with a streamer, bearing the word “Constitution,” upside down. Then they had a grand “pow-wow,” and apparently had a good time generally. The whole affair was evidently got up for the purpose of “roping in” outsiders; but we hope with no effect. The whole affair is so transparent that nobody but very silly people can be deceived. The conduct of the Secessionists reminds us of what some travellers tell us about the habits of the ostrich. When it is pursued and wishes to escape observation it thrusts its head into the nearest sand heap and leaves its body sticking out. Not until it feels the blows of its pursuer does it find out its mistake. The Union party very plainly see the body of Secession sticking out of all these so called Democratic demonstrations, although its head is hidden; and when the day of next election comes we hope that a vigorous application of boot-toe will emphatically convince the Secesh ostrich that it has deceived no one but itself.

– Petaluma Argus, August 5, 1863BADLY SOLD.–The Constitutional Democracy were badly sold last Sunday. W. L. Anderson telegraphed from Santa Rosa that Dr. Harris, Willson and Valentine, three noted rebels of Sebastopol, had been arrested for treason and would be sent to Alcatraz. As the despatch came from a rebel, they believed it to be true, and many a long face might have been observed on our streets.

BADLY SOLD Until the evening stage arrived in Petaluma with news that the report was false, the earlier report in the telegram from W. L. Anderson, a rebel from Santa Rosa, was believed – that three noted rebels of Sebastopol, Dr. Harris, Wilson and Valentine, had been arrested for treason and would be sent to Alcatraz. A constitutional expounder in Petaluma offered to bet $500 that the arrests resulted from the lying of the awful fellow, Joe McReynolds. Democracy rejoiced with great joy and the indulgence of “tangle leg fluid” when the initial report was exposed as a hoax.

– Petaluma Journal and Argus, July 28, 1864MEAN

A subscriber of the Argus at Sebastopol complains that he gets very little from his subscription since his Secessionist neighbors read and circulate his paper from house to house and he is seldom able to read his own paper. “This is just like the rebels here. They sneak around get the reading of the paper and then talk all week of the march of vile abolition ideas.”

– Petaluma Journal and Argus, December 1, 1864Editors Alta: Yesterday evening a circumstance occurred here which illustrates the principles of the Copperhead Democracy so perfectly, that I must give it to you for the benefit of your readers. On the 3rd, Mr. Gordon Peters, a Union man, went to the house of Aaron Barnes, a Democrat, for the purpose of purchasing a wagon load of fruit. Terms were agreed upon between the two for a load, and Peters was invited to stay all night. In the evening, about 9 o’clock, Barnes commenced talking about the state of the country, and finally asked Peters what he thought of the arrest of Vallandigham.

Peters replied that he thought it was right and proper, whereupon Barnes commenced abusing him, and told him no Abolitionist should stay in his house, and that he must leave; which he had to do, team and all, but without the fruit. The above facts I had from Mr. Peters himself this morning, and as he is a man of first-rate standing, there can be no doubt about their truth. Comment is unnecessary.

– Daily Alta California, August 8 1863ANOTHER SEBASTOPOL – The name of the Post Office at Sebastopol, Sonoma County, has been changed from Bodega to Sebastopol, and John Dougherty has been appointed Postmaster thereof. The name of the Post Office at Smith’s Ranch will be changed to Bodega. These changes have become necessary by the settlement of the country. Bodega Post Office hitherto has been located at the town of Sebastopol, fully ten miles from Bodega Corners, and the Post Office at the latter place has been known as Smith’s Ranch. The names are now made to conform to the localities more nearly than before. The Bodega (now Sebastopol) Post Office was the oldest established in the county except that at Sonoma, and its establishment was the most northern Post Office above the Bay of San Francisco and west of the Sacramento Valley — letters for everyone up to the Oregon line being sent to that office. We now have three Sebastopols in California, but only one of them has a Post Office by that name. The Post Office at Sebastopol, Napa County, is now called Yountsville [sic], and the Sebastopol in Sacramento County had no Post Office at all, so far as we are informed.

– Petaluma Weekly Argus, January 23 1868The wedding of Mrs. Josie Burk, of Santa Rosa, and Aaron Barnes, of Sebastopol, took place on Sunday afternoon of last week at the residence of C. A. Reigels, on Sonoma avenue, in the former place. Smilax and cut flowers adorned the parlors. The ceremony was performed by the Rev. T. H. Woodward, in the presence of the relatives and a few invited friends. After the marriage rites, a wedding supper was served at tete-a-tete tables, where the bridal cake was cut. The health of the bride was drunk by those present in bumpers of sparkling wine. The young couple left the following day for Lake county to spend the honeymoon.

– Daily Alta California, July 27 1885

Wedded Again.(Healdsburg Enterprise.)Some five weeks ago Aaron Barnes, a very wealthy citizen, of Green Valley, lost his wife. Though on the shady side of life, between seventy and eighty years of age, the old gentleman concluded that the term “single blessedness’ was a misnomer, and a short time since commenced looking about him for another partner. He met a musical gentleman named Professor Parks, to whom he proffered $500 in consideration of his finding him a suitable wife. The Professor readily accepted, and in a short time a lady from the East, twenty-seven years of age, attractive and cultured, agreed to share the old man’s wealth. The latter desired to settle upon his fair young intended $30,000, besides two cottages in Santa Rosa,and her legal advisor pressed her to accept, but it seems she was modest, and would receive but $10,000 in money. On the strength of this they were duly married, and it is stated that few men are prouder to-day than the happy groom.

– Daily Alta California, August 5 1885

Aaron Barnes Sues His Wife.Aaron Barnes of Sebastopol was married to Jessie Burk in 1885, and they lived together as man and wife until August, 1892, when she left him. Previous to tbe marriage the plaintiff deeded to the defendant $14,000 in personal property, and now be wishes to recover $20,000 in damages for breach of contract. The defendant appeared by demurrer Monday before Judge Dougherty, and while she admits the facts of desertion as alleged, sbe denies the conclusion and the breach of contract. In his judgment sustaining the demurrer Judge Dougherty says that as the sole consideration of the contract and transfer of the property was marriage and the marriage had been executed, therefore desertion afterwards could constitute no breach that would effect the property transferred to her, although tbe parties were not living together since 1892. The plaintiff sets up the plea that the defendant was not a worthy woman at the time of the marriage, and that it was a scheme on her part to obtain possession of his property, and that part of the plan of the defendant was ultimately to leave him. To all this the defendant filed a demurrer and the judge sustained the demurrer and granted ten days for tbe defendant to amend.

– Sonoma Democrat, October 13 1894

Regarding Aaron Barnes:

He was my great-great grandfather and his full name was Aaron Henry Barnes who married Lydia Harlan.

The story about his second marriage is definitely strange. I already knew the story and those of us who are his descendants are sure that he had dementia by that time! It actually happened and you can track all the court cases regarding it.