To understand the origin of the rivalry between Santa Rosa and Petaluma, think of the relationship between the Smothers Brothers.

In their classic comedy routines Dick (the one who plays bass) is the smarter of the pair, cool and sometimes smug; Tommy usually plays the man-child, a dumb cluck who becomes flustered and petulant when Dick deflates his goofy ideas. (Yes, I know Tom is actually older than Dick, Tom was the genius behind their legendary TV show, these are just their comic stage persona, &c. &c. so don’t start blasting angry tweets.)

I don’t want to press this analogy too far, but in the late 1850s Petaluma was something like Dick Smothers, needling his kid brother when he would screw up or begin crowing as if he were cock of the walk. And Tom/Santa Rosa would usually be on the defensive, sometimes getting a bit whiny about not getting his due respect even though he was trying really, really, hard.

Santa Rosa was voted to be the county seat in 1854, although at the time it was little more than a camp staked out at a muddy crossroads with only about eight actual buildings. The place had no purpose to exist other than to be a county seat; the numerous squatters in the surrounding area needed a centralized courthouse for pressing their shaky homestead claims. For more background on all that, see “CITY OF ROSES AND SQUATTERS.”

|

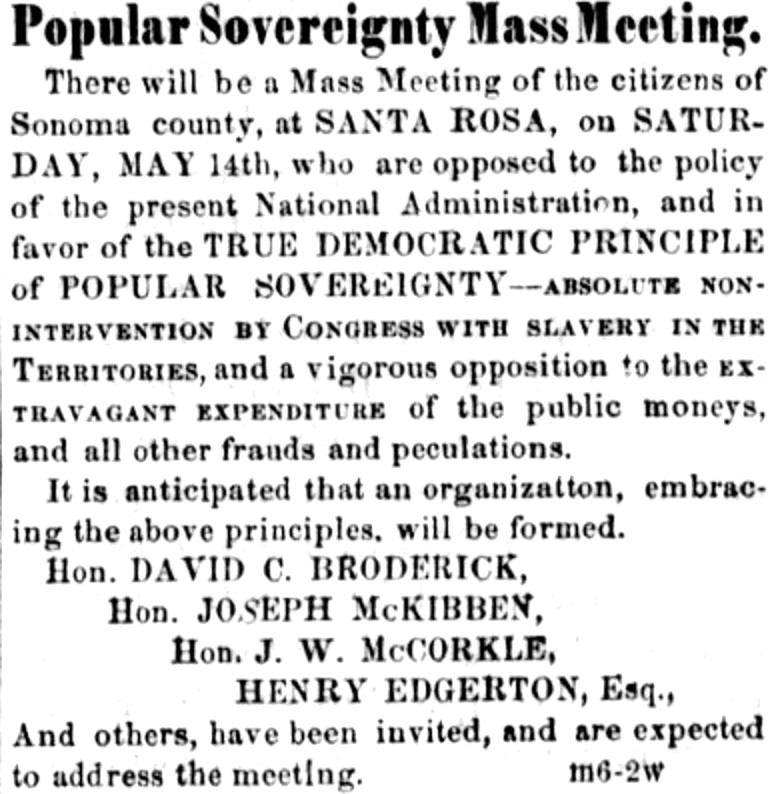

| Sonoma Democrat, May 5, 1859 |

Petaluma had a two-year head start. While Santa Rosa was mapping out its first streets in 1854, Petaluma was already an established community with several hundred residents. They had stores and hotels, churches and meeting halls. A sketch of the town from the following year shows a mix of single and two story buildings – simply built, but not shacks, either.

Part of the deal for Santa Rosa to become the county seat required it to provide a courthouse before the end of the year. This courthouse issue would become the town’s Waterloo – or maybe a better comparison might be an albatross around Santa Rosa’s neck. (Arguing whether a bad situation is more like a dead bird or a lost battle would actually be a great setup for a Smothers Brothers routine, but enough of analogies within analogies.)

Santa Rosa’s first actual courthouse was a rush job – a temporary building later described as “a small wooden building built of rough up-and-down boards and ‘battened'” on Fourth street close to D st. Meanwhile. planning began for a permanent courthouse and jail at the current location of Exchange Bank.

Work on the courthouse/jail began in the summer of 1855 and finished just after Christmas. The Board of Supervisors called a special meeting afterward where they refused to pay the contractor, claiming the building didn’t meet specs. “Both sides got mad,” Robert Thompson wrote with considerable understatement in his history, “Central Sonoma.” After weeks of arguing the Board agreed to accept the work, albeit at a much reduced price.

Now shift forward a couple of years: The 1858 county Grand Jury declared the nearly-new courthouse was unsafe, dangerous and a “public nuisance,” with the roof leaking and walls cracked. Those drips and cracks foreshadowed a decade of woes ahead; later repairs and do-overs would about triple the cost of the original construction.1

By now Santa Rosa had its own weekly newspaper, the Sonoma Democrat, which charged the Grand Jury had “an unnecessary amount of spite at the courthouse.” Sure, the roof leaked, but it could be repaired. While there really were big cracks in the walls, “…we sincerely congratulate our county that they remained standing long enough to save the invaluable lives of this Grand Jury, and thereby reserved to future generations the vast amount of wisdom contained in their heads, and which thus far has been so sparingly imparted to their less favored fellows.”

While Democrat publisher/editor E. R. Budd pretended to laugh off the building’s problems, the Grand Jury’s findings clearly rankled; two years later – after many had likely forgotten all about it – he dredged it up again, sulking their courthouse remarks were written by “two or three Petaluma men” on a subcommittee.

|

| The Hall of Records and Courthouse with the jail between them, 1875. View from Third street overlooking the west corner of the original plaza. Main photo Sonoma County Library |

Mr. Budd appeared to be a fellow of unusually thin skin for a newspaper publisher as the Petaluma papers teased and taunted Santa Rosa. The same year as the Grand Jury report, the Courier ran a (probably fictitious) story about an out-of-towner visiting Santa Rosa and being unable to find anything that looked like a courthouse. Budd took the bait and reprinted it as part of an editorial titled, “Envy:”

| The following specimen of petty spleen, shows how bitterly envious some of the inhabitants of Petaluma are of the place chosen by the people of this county for the county seat…it is quite evident that some of the more selfish denizens of Petaluma have been unable to appreciate Santa Rosa, and would like to make those at a distance look upon it in a similar light… |

Budd also complained Santa Rosa was undermining itself. A bit later he wrote a lengthy editorial about his paper not getting the local support it deserved, carping that many local businesses “have not done their part” by taking out ads. There he also made a passing remark that, if close to true, provides valuable insight into how they lived at the time: “…one half the people composing this community go to Petaluma to trade.” As Petaluma was probably 90 minutes away (at least) by buggy or wagon, that shows Santa Rosa was still mostly an outpost in 1858.

But Santa Rosa’s fortunes began looking up the following year. We have an unofficial census of Santa Rosa from 1859 showing the town’s population and an inventory of businesses. (There’s a similar census of Petaluma from 1857, which enables us to neatly compare both towns at their five-year mark.)2

Primary among the new businesses was the Wise & Goldfish general store on the east side of the plaza – Santa Rosans finally had a real place to shop. “Dry Goods, Clothing, Boots, Shoes, Groceries, Hardware, Crockery, Glassware, Fancy Goods, Bonnets, and a general assortment of Ladies’ Goods,” boasted their first ad in July, 1859. Their prices were also the lowest in the North Bay, they claimed. But now that Petaluma’s hegemony over retail sales faced serious competition, the journalistic jibes from that town were no longer quite so brotherly.

Petaluma’s Sonoma County Journal ran an article on that Santa Rosa census which is mostly transcribed below. Read it carefully and you’ll find editor Henry Weston was actually damning Santa Rosa with faint praise.

The article slyly implied land titles in Santa Rosa might be disputed because of legal problems with its underlying Mexican land grant (in truth, the title situation here was among the cleanest in the state, beating Petaluma to approval by eight years). It exaggerated how much had been spent on the county buildings so far while pointing out “their present unfinished state.” And the article noted “the population of the town proper is about 400,” although the federal census the next year would show Santa Rosa was really four times larger after people in the surrounding township were included.

But the worst of it was their long list of Santa Rosa businesses, which included this bit: “…one shoemaker shop, one jeweler shop, eleven Jews, one paint shop…” (emphasis added).

Needless to say, the actual 1859 census did not include “Jews” as a business category (you can find the entire list in Thompson’s history). This was sheer anti-Semitism by the Petaluma paper and clearly aimed at undermining the Wise & Goldfish store, which was owned by the only Jewish families in town. In the history books H. L. Weston has been admired as the godfather of the Argus and Petaluma newspapering in general, but this calls for his sterling reputation to be reevaluated.

Increasingly nasty potshots between the town papers continued the next year, with the Argus accusing that county taxes were being used to pay for civic improvements in and around Santa Rosa (one of these items can be found below). But the final salvo in this early skirmish was the 1861 effort to move the county seat to Petaluma.3

Very little was written about this at the time or since; it appears neither Santa Rosa nor Petaluma newspapers took it too seriously – and as everyone was preoccupied with the Civil War which had just begun, that’s really not so surprising. The proposal popped up suddenly in California newspapers in March, 1861, as a petition was presented to state legislators. It’s unknown exactly what it said or how long it was circulating. A counter-petition was quickly organized, arguing that it was “unnecessary, unwise and burdensome” to move. The “stay” counter-petition supposedly had far more signatures.

As Sonoma county then was deep in debt, the Santa Rosa paper argued taxpayers couldn’t pay for a new set of buildings, and it was unlikely that Mr. Petaluma was going to open his purse for the honor. “It may be, however, that some wealthy citizen is about to immortalize himself by presenting some ‘noble edifice’ to his fellows! Happy thought! Toodles forever!” The Democrat also sneered Petaluma merchants were mistaken if they expected a windfall from providing “grub, liquor and lodging” to people coming to the county seat to appear in court.

There were no rallies for or against, as far as I can tell, and editorial support for the move in the Argus was tepid, particularly after it was mentioned some subscribers were so opposed to the idea they might boycott the paper. When it came to voting day the measure was soundly defeated, passing in only three of the county’s 18 voting precincts (including Petaluma, natch).

And with that, the bell rang to end the first round of Petaluma vs. Santa Rosa. The next part of the slugfest saw the editors of the Argus and Santa Rosa’s Democrat take off their gloves for bare-knuckle fighting over the Civil War, as told here in “A SHORT TRUCE IN THE (UN)CIVIL WAR.”

Before wrapping up this survey of 1855-1861, my newspaper readings from those years also turned up some details that may shed light on an important but murky question in Sonoma county history: Why was almost everywhere outside of Petaluma so anti-Lincoln and pro-Confederacy before and during the Civil War?

In 1859 there was a meeting in Santa Rosa to organize a local Democratic party committee endorsing “popular sovereignty,” which was the concept that every state and territory had a right to set its own laws and rules, even on slavery. While there were meetings like that nationwide with the general goal of getting pro-slavery delegates elected to state Democratic party conventions, here in Sonoma county it piggybacked onto the politically powerful settler’s movement, which had its own definition of sovereignty – namely, it wanted California to declare the Mexican and Spanish land grants “fraudulent,” in violation of the federal treaty with Mexico that ended the Mexican War. (Interested historians can read the full set of resolutions in the Sonoma County Journal May 20, 1859.)

This fusion of “settlerism” with “popular sovereignty” may help explain why Sonoma county overwhelmingly voted against Lincoln the next year in favor of the Southern Democrat candidate who wanted to uphold slavery as an absolute Constitutional right. Maybe it wasn’t so much that the majority of the county was saying “we like slavery,” as “we’ll vote for any guy who might get us clear title to our land claims.” This is an important distinction I’ve not seen historians discuss.

1 The courthouse construction in 1855 was just for the first story, not the two story building with cupola seen in all photos. In 1859 the top floor was built and again there was a fight with the contractor. His final bill included a whopping 75 percent cost overrun, presumably related to fixing structural problems with the underlying building. Again it went to arbitration, this time the contractor settling for about a quarter of what he asked. Problems with the original shoddy construction still were not over – the jail had to be torn down and completely rebuilt in 1867, just eleven years after it originally opened. |

2 In 1857 Petaluma encompassed about a square mile, with a population of 1,338. Santa Rosa in 1859 was still its original 70 acres, with 400 residents. The decennial federal census of 1860, however, shows Santa Rosa with the larger population: 1,623 compared to Petaluma’s 1,505. This is due to counting people in the entire Santa Rosa Township, not just within city limits. The 1860 census of Santa Rosa proper was 425 residents. |

3 One legislator hinted the proposed move of the county seat to Petaluma was (somehow) part of a scheme to have Marin annex Petaluma away from Sonoma county, and just the year before Marin actually had asked the state to expand their border northward and make Petaluma their new county seat. Those two efforts are probably linked but I haven’t found anything further on that angle, or who was behind either effort. It sounds like a good story, tho, and I’ll write more about it should more info surface. |

|

| Sonoma Democrat, May 5, 1859 |

SANTA ROSA–OUR COUNTY SEAT.– To those who have only heard of Santa Rosa as the county town of Sonoma county, and as being one of the most beautiful and thriving places in the State, the following facts and figures, condensed from the Santa Rosa Democrat, may be interesting:

The town of Santa Rosa is built on the fertile valley or plain of the same name, and on the old Santa Rosa “grant,” midway between Petaluma and the flourishing town of Healdsburg, on Russian River. To the enterprise of Berthold Hoen is the site of the place, and much of its prosperity, due. The site was fixed by him, and by him surveyed and mapped in the spring of 1854. In the year 1855, it was declared the county seat, Mr. Hoen tendering the county a building gratuitously, to be used for county purposes. The entire cost of the county buildings will be about $35,000, and even in their present unfinished state, present an appearance in structure and design creditable to the rich county of Sonoma. When completed, they will, in elegance and design, be surpassed by but few such buildings in the State. The private residence are mostly one-story cottage buildings, and for neatness and comfort will vie with those of any other county village we have knowlege of. The soil of the valley is a rich alluvium…

…Beside the public buildings, there is a fine academy for males and females, (accommodating 250 pupils); a district school, (numbering over 60 children); two churches, two resident preachers, nine resident lawyers, five physicians, two notaries public, one printing office, from which two publications are issued, seventy-five private residences, nine dry goods and grocery stores, one drug store, one hardware store, two hotels, two restaurants, two drinking saloons, two daguerrean galleries, one saddler shop, one barber shop, one tailor shop, one shoemaker shop, one jeweler shop, eleven Jews, one paint shop, three carpenter shops, two butcher shops, one cabinet shop, six blacksmith shops, one pump shop, one bakery, and two first-class livery stables. The population of the town proper is about 400. The climate is mild and salubrious, not being troubled so much by fogs and head winds, as the towns bordering on the coast. The greatest drawback is the unsettled condition of land titles — not peculiar to our own county — and these are in process of adjustment.

– Sonoma County Journal, November 25 1859…Below, we give a small specimen of this talk, taken from the Argus of the 13th Jan. The editor goes so far as to call his statement “the prevailing opinion in this section,” (Petaluma):

“That Santa Rosa and Santa Rosa interests are being built up and protected, at the expense of the whole County, and to the detriment of some particular sections. That this has been, and now is, the policy of the citizens of Santa Rosa, no observant man, with any regard for truth, will dare deny. The governing policy for the last four years, has been to concentrate everything at Santa Rosa. No roads could be made unless they centered there. No bridges built, unless they benefit Santa Rosa. No regard is paid to the wants of Sonoma, Petaluma, and Bloomfield. But if Santa Rosa wants anything, even to the fencing of the plaza, the door of the county safe is thrown wide open. It is time these outrages upon the people at large should cease—this squandering of the public money for the benefiit of a few property-holders in and about Santa Rosa.”

We believe that the statement that the above is “the prevailing opinion” in that section, is untrue. That there are a few discontents in Petaluma, who find fault with this, as they do with everything else in and about Santa Rosa, is quite likely ; and that these compose the associates and intimates of the editor of that sheet, is still more probable. But we have no reason to believe that he is ever entrusted with the opinions of respectable men, even of his own vicinity. The quotation above, contains as much bare faced untruth, as we ever saw distilled in so small a space…

[lists county officials from Petaluma and Healdsburg, the 1858 Grand Jury report was the work of “two or three Petaluma men” on a committee]

…It is indirectly assorted, that the county authorities have paid for the fencing of the Plaza. This, of course, is just as reasonable as any other assertion; and yet not one dollar, directly or indirectly, has ever been paid or asked for for any such purpose. Equally false is his assertion of the building of bridges and roads for the exclusive benefit of Santa Rosa. Not one of the kind has ever been made. Altogether, we regard these complaints as very remarkable, even as coming from Pennypacker — certainly, they could come from nowhere else. [J. J. Pennypacker was the first publisher of the Argus 1859-1960 – JE]

Notwithstanding all this Billingsgate we speak of, seems to come from Petaluma, we are happy in the belief that the community in and around that place are not chargeable with them, but that among the respectable portion of that locality, a more liberal feeling exists.

– Sonoma Democrat, February 2 1860