Ads in the Santa Rosa newspapers a century ago could be quaint, silly or downright fraudulent, but some required a double-take – did I really see that in the paper? Here is a sample of ads from 1911-1913 that require some explanation:

Actually, this ad, which appeared in the Press Democrat for a week, probably doesn’t require any explanation at all. Great grandma certainly looks happy with her Arnold Massage Vibrator.

Great scott, did a 1911 vaudeville act really include a live grizzly bear? All sorts of trained animal acts appeared on stage in Santa Rosa: Dogs, monkeys, even goats. But even when raised from a cub by humans, grizzlies are famously temperamental – goddesses know what might happen if one was frightened or angered by rowdy drunks in the audience.

As it turns out, the grizzly was a guy in a bear suit with La Angelita and “Petus” doing the “Grizzly Bear” and “Texas Tommy,” so-called rag dances that Petaluma and other cities banned for being indecent. That it was a novelty dance act was remarkably difficult to learn – newspapers presumably didn’t mention that angle so as to not spoil the surprise. Once the ragging craze faded La Angelita began appearing with two other women as costumed Spanish dancers. The ersatz grizzly still showed up for the finale, which confused a reviewer for Variety: “The only drawback to the act is the bear dance, wherein a man parades in a bear skin.”

Another reason it first seemed the act involved a real grizzly was because at least once they appeared on a bill with actual trained bears, “Albers’ Ten Polar Bears.” Apparently that act mostly consisted of the animals rolling a large ball up and down a slide, although the 1911 Oakland Tribune noted, “Herr Albers promises to give them a big feed during the matinee Saturday, so one can imagine the fun while these ten tons of Teddies are at their porridge.” Hopefully they went on last so the stage could be hosed down afterward.

Oh, the good ol’ days, when someone could shop downtown for large containers of lethal poisons. Painting your house? In 1912 you could stop by the Asbest-o-Lite Paint Company on Fifth street and pick up a few gallons direct from the factory. And doesn’t everybody love the smell of fresh paint? Take a good whiff while they mix your color! And if it’s spring, don’t forget to spray your fruit trees with lead arsenic, that safe and economical insecticide.

They did’t know at the time that inhaling lots of asbestos can cause a particularly nasty form of cancer, so it was widely used at the time – in roofing, flooring, wall insulation, wrapped around hot water pipes, lining the interior of forced-air furnaces, and much, much more. Asbestos paint was probably the least dangerous form of exposure as the stuff wasn’t blowing around, but you wouldn’t have wanted to be anywhere near the factory while it was being made. The Asbest-o-Lite Paint Company apparently lasted only a year.

Lead arsenate was heavily used as an insecticide in the first half of the Twentieth Century (good history here) although it was discovered after World War I that it didn’t easily wash off produce completely and contaminated topsoil. Yet until the introduction of DDT in the late 1940s everyone bought the stuff by the tub.

It was particularly risky for people who handled the stuff in the fields, but only California and a handful of other states recognized long-term exposure could be an occupational disease. Making matters worse, it was common to use it as part of a “bordeaux,” mixing it with other arsenics such as Paris green – a fungicide and also the main ingredient in rat poison – so all spraying could be done at the same time. That cocktail nearly made quick work of Henry Limebaugh, a farmer near Hessel in May of 1912 when after spraying his fruit trees he forgetfully took a sip from the same hose, leading to an emergency visit from a doctor.

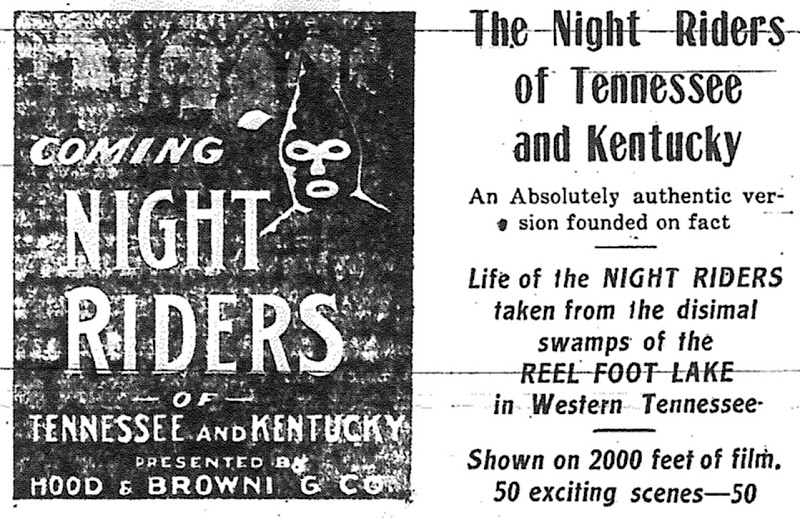

Was that a movie about the Klan playing at the Nickelodeon?

D. W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation,” is credited with inspiring (and to some degree, inventing) the modern Ku Klux Klan. But that film was not made until 1915; playing here in 1911 was “Night Riders of Tennessee and Kentucky.” A synopsis printed in the Santa Rosa Republican showed it villainized them and since this movie is not mentioned in any cinema history, it would be a pretty big deal to find there was an earlier film with an antithetical view to Griffith’s glorification of the sheet-wearing vigilantes.

It turns out the film was first shown elsewhere in 1910 and the “Night Riders” weren’t the Klan at all – it was about the recent Dark Patch Tobacco War. Once it had a monopoly, the American Tobacco Company sharply dropped what it paid farmers to less than it cost to grow the tobacco. They organized a boycott and formed an association to warehouse the crops until prices returned to normal. The company offered top dollar to any scab growers who would sell their tobacco; in turn, the association organized hooded Night Riders to enforce the boycott by intimidating those sellers, usually burning their fields. The conflict ended in 1908 when the Kentucky National Guard was called up to suppress the Night Riders.

How much of the film was “founded on fact” is impossible to say as no copies survive, but it was most likely propaganda created by the American Tobacco Company to demonize the growers and place the company in a good light. When copies of the movie were circulating in 1910-1911 the company was fighting government charges that it was an illegal Trust and should be broken up (in 1911 the Supreme Court ruled it was indeed a monopoly). Further evidence that it was underwritten by the company is that Mr. Hood and Browning – whomever they were – toured with the movie and narrated it. While live stage appearances with films were presented in that era, it was only in major theaters in big cities and at a premium admission price, not showing weekday nights down at the Santa Rosa Nickelodeon for a dime.