Breaking news: People tend to have very strong opinions about parking meters. Also, this surprise: Those opinions are never favorable.

Yet Santa Rosa still has them, making it among the very few places in Sonoma county where the elusive meters can be spotted in the wild along with their related species, parking garages that charge money. And the reason we have them is because this is the city that time forgot – in Santa Rosa, it is always 1946.

This is the second in a series exploring the missed opportunities and regrettable decisions that have shaped Santa Rosa since World War II. Part one (“THE SANTA ROSA THAT SHOULD HAVE BEEN“) saw voters narrowly reject a chance to develop part of the downtown core into a Civic Center, which would have kept it the county’s hub during the postwar boom years and after.

Looking back on all the other times the city took a wrong turn, one name keeps popping up: Hugh Bishop Codding. When first planning this series I even considered naming it “How Hugh Codding Destroyed Downtown,” but that’s unfair – our city government and elected officials did the job on their own, advised by a parade of out-of-town “experts.” Yes, old Hugh monkeywrenched the town with lawsuits and sometimes jujitsued the city or county into doing something stupid, but mostly he took strategic advantage of their missteps. And sometimes he didn’t win; for example, there was his odd and long-running quest to convince the city of Santa Rosa to move out of the city.*

No, Codding’s not to blame alone; with remarkable consistency, when challenged to make a momentous decision our trusted civic leaders boldly rose to the occasion and (in my humble opinion) made the worst possible choices. The courthouse was torn down and a street plowed through courthouse square; Santa Rosa Creek was buried in a culvert; prime downtown acreage was bulldozed with most of it turned over to private developers; a shopping mall was constructed which immediately became the Great Wall of B street.

That record of stumbling mistakes began in July, 1944, while Codding was still a Seabee building quonset huts in the Pacific. That month the Chamber of Commerce held a luncheon to discuss the “parking bugbear” with a public meeting following a few weeks later. There the city manager announced he had contacted 200 colleagues in other cities; almost all said parking meters were swell. The Press Democrat thought the general attitude by the end of the meeting was that “they are at least worth a trial.”

Letters began pouring into the PD disagreeing with that. While there were a couple of correspondents who made somewhat reasoned arguments, most teetered on the edge of crackpottery. A few samples:

“Where is our freedom? What are our men fighting for? Now comes it the parking meter…” (Mrs. A. K. Larson). “Parking meters have to be placed on the sidewalks. Our sidewalks are already too narrow. You put a row of posts on the walks in addition to the present stacks of bicycles and there won’t be much room for pedestrians” (“A Taxpayer”). “If parking meters are installed here, we would have buildings going up outside the city limits after the war and the city assessor would have to reduce the taxes on the buildings downtown as there will be many vacancies” (Alfred E. Poulsen). “I believe this to be illegal. Property owners own and pay taxes to the middle of the street” (E.J.F.). “Why charge the motorist all the time? Look up all the hidden taxes he pays. Why not charge pedestrians for standing on the sidewalks? It is just as fair” (Sgt. A. R. Milligan). Bonus crankdom: The letter following Sergeant Milligan’s in that edition advocated that once WWII was over, we should sterilize all German males for the next twenty years to ensure “any children born in Germany would have to be at least half civilized.”

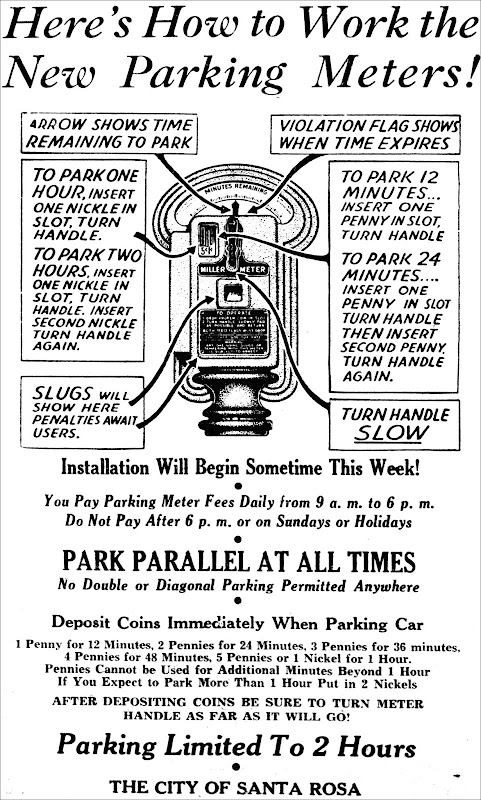

The city installed 510 parking meters in early 1945 and although the city printed helpful directions on how to use them, on the first day of operation “numerous persons inserted coins ‘just to watch them work’ but in many cases failed to turn the handle far enough to set the ticking device in operation.” When the first monies were collected three days later, the take included four slugs even though the graphic in the PD showed a little window on the meter claiming “SLUGS will show here.” Yeah, no.

|

| Press Democrat, February 11, 1945 |

A nasty squabble immediately arose between the county and city over parking spaces. Santa Rosa had installed a row of meters on the east and west of the courthouse and the county was threatening legal action unless there was free parking for designated vehicles. As neither side was blinking, the county proposed it would turn the south lawn of the courthouse into a government parking lot, requiring chopping down two mature Peruvian pine trees – which were the last survivors from the pre-1906 earthquake courthouse plaza. The PD reported on the backlash: “The number and vehemence of telephone calls coming to this office since announcement of the parking plan indicate that the removal of those trees for the purpose set forth will meet with a storm of protest, like which our county officials have never before heard.” The city caved, but it was a stupid fight to pick; what did they expect? Jurors and judges would dash outside every two hours to move their cars?

Then as Mrs. Larson poetically wrote, now comes it the crisis: the year 1946.

Thousands of soldiers and sailors were returning home to Santa Rosa where they were promised free education and cheap mortgages by the GI Bill – but found jobs scarce and nowhere to live. The housing situation was probably worse than it’s been since the 2017 fires; a special census taken that February found only 74 vacant houses or apartments in all of Santa Rosa, including places leased/sold but not yet occupied and units where residents happened to be out of town. The Press Democrat’s “Wanted to Rent” classifieds were always long, packed with veterans pleading for somewhere with a roof. Sometimes a finder’s fee was offered, including nylons.

With all those additional people on the downtown streets, the traffic situation became nigh impossible. The meters and rigorous enforcement of time limits became essential to avoid gridlock. Yet at a city council meeting the outgoing mayor conceded something had to be done besides writing lots of parking tickets (“I don’t like these wholesale citations”) and that the parking meters “have not accomplished everything wanted.” From the March 6th PD:

| The mayor explained that it is “not the fault of the meters” that the parking meters have not completely solved the parking problem, but is due to the “great influx of people into Santa Rosa.” He explained that traffic has become so great that “there just isn’t room for them” in parking space now provided. |

Besides sounding a bit like a Stockholm syndrome hostage to the Miller Meter Company, the mayor urged the council to acquire empty lots close to downtown for off-street parking – which would mean buying more meters, of course. (There was at least one all-day parking lot at B street and Healdsburg ave, and it was never mentioned whether the 10¢ required to park there was fed into a meter, handed to an attendant or was a purchased tag.)

To pay for the lots and other civic improvements (including “electric stop-and-go signal equipment for key intersections”), the city council used bond money and authorized Santa Rosa’s first sales tax, to predictable taxpayer howls. Although the tax was only one percent, there were calls for a complete boycott of the downtown as a kind of “Boston Tea Party” protest.

The Press Democrat’s letter section saw writers interchangeably angry between the sales tax and the parking meters, to wit: “I (Someone I know) will never shop again in Santa Rosa because I’m mad about a parking ticket (I already pay too many taxes).” But where else were they to go? Spend all that time and gas – now up to 21¢ a gallon! – driving to Petaluma for groceries or all the way to San Francisco for a fashionable hat?

Hello, Hugh Codding.

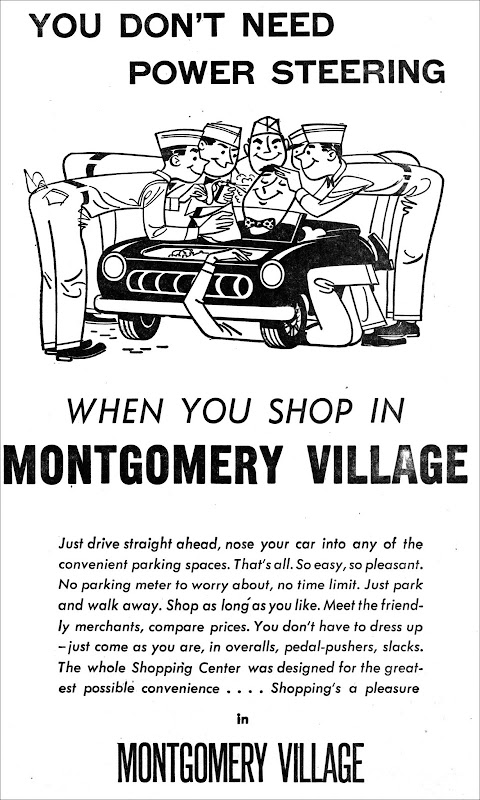

The very first real article in the Press Democrat about Montgomery Village appeared on April 30, 1950 and included this quote from Codding: “People do not like the inconvenience of looking for parking space, priming the parking meter and then walking several blocks between stores. Montgomery Village abolishes that inconvenience – all within one block of 750-car parking.” It had been a long time since Santa Rosa had heard such sweet and sensible words.

That appeared before the shopping center fully opened, and later ads would feature its other major draws: Montgomery Village was just outside city limits so there was no municipal sales tax and it had diagonal parking.

To understand why diagonal parking was such a Very Big Deal, slip into a Dacron jacket and travel with me back to 1950. Cars and pickups are classy but clunky – as large as boats and heavy as little tanks. And because they don’t have power steering (not available on any car until 1951) they require the muscles of Popeye to turn the steering wheel if the tires aren’t in motion.

Santa Rosa insisted upon parallel parking only, even though downtown merchants had been protesting it for many years. A petition for diagonal parking was presented to city council in 1940, headed by some of the top storekeepers: Lee Hardisty, Leonard Deffner, Donald Carithers and Irving Klein. Deffner, owner of the big Pershing Market between 4th and 5th streets, told the council that customers of nearby businesses were using his grocery store parking lot rather than parallel park on the street (and this is before the meters, remember). Nothing doing, said Santa Rosa – our streets are so narrow that anyone double parked would cause a traffic jam if diagonal was used. Apparently stiff fines for double parking weren’t a consideration. The city clung so hard to parallelism that in 1964 they made every third space no-parking so it would be faster to nose or back in to a spot, thus making the parking shortage 33 percent worse. Dumb decisions like that made Codding look like a genius by comparison.

|

| Montgomery Village ad, February 6, 1955 |

While Montgomery Village was thriving, Santa Rosa seemed to go out of its way to make downtown parking ever more annoying.

In 1951 (840 meters now installed) they made a deal with a company to put frames on the meter poles which could display printed ads. Local merchants hated it, didn’t advertise and the company damaged many of the meters somehow. Two years later the city incurred more public wrath by switching parking lot meters to take dimes only, thus forcing drivers to overpay if their errands took less than two hours. Overtime parking fines doubled, then doubled again.

Other Sonoma county towns followed Santa Rosa’s lead in the 1950s and installed parking meters, then later removed them under pressure from the business community. Healdsburg uprooted its meters in 1964 and the sales tax increase more than replaced lost meter income. Twenty years later Petaluma stopped meter enforcement and their Downtown Merchants Association saw business improve.

Yet Santa Rosa’s confidence in the meters remained unshakable, even while the city continues to tinker with them; a decade ago they tore the meters off most posts because consultants insisted ticket kiosks were ever more efficient and the public really wouldn’t mind hiking from a parking spot to a kiosk and then back again. This year (2018) the city extended metered parking to 8PM while also implementing a zone system, which is able to increase the cost of parking in busy areas during the busiest times – which was done because experts told the city that trick works really well in tourist towns like San Diego.

But still the ungrateful public keeps complaining and today the resentment over paid parking in Santa Rosa is louder and more frequent than ever before – although that may be because the forum has shifted from newsprint to social media, where everything is amplified and unedited.

What’s interesting is how attitudes have not budged a whit between 1946 and now. People still say they no longer go downtown because they (or someone they know) was unfairly dinged with an expensive parking ticket. Businesses still say they don’t have enough customers because of the hassle of parking. And Santa Rosa still says there’s nothing wrong with the status quo – whatever that happens to mean right then.

* There are no shortages of Hugh Codding anecdotes, but here’s a story I’ve not read elsewhere: While Santa Rosa was mulling over where to build the new city hall in 1950, Codding offered space at Montgomery Village – although it was then outside of city limits. According to the Press Democrat: “‘I thought myself it was fantastic until I got to thinking about it,’ he told the astounded [planning] commissioners.” Then as the city still hadn’t decided in 1963, he offered free land near Coddingtown in the unincorporated area. The city council didn’t snap up the deal so a week later he came back with an offer of another place, also on county land near his shopping center. And when they still didn’t bite, he tried to broker a deal to make city hall part of the new county administration center. Did he really believe he could get Santa Rosa to move the city buildings out of the city? |