Prohibition is starting soon, or maybe not. When it begins (if it does) enforcement will be really strict, or the law will be mostly ignored. No alcohol will be allowed anywhere, or there will be exemptions for wine and light beer.

The year was 1919 and anyone who claimed to know what was going to happen was a fool or a liar. Both probably.

This is the story of how Prohibition came to be the law of the land. Before continuing, Gentle Reader should not expect the sort of tale usually found here. Santa Rosa or even Sonoma county are not center stage; this time our ancestors are in the audience, where they would have been watching with rapt attention and gripping their seats tightly – because the ending of this drama just might end up causing financial catastrophe for many dependent upon the wine industry.

In 1918-1919 most Americans likely thought there were long odds that a completely “bone-dry” version of Prohibition would be enacted. Several times during the lead-up it seemed there were going to be exemptions for beer and wine, or the law would be toothless because it wouldn’t be enforced, or the amendment would be tossed out as unconstitutional. All of this kept the nation (and particularly, wine-making Sonoma and Napa counties) on edge.

What happened nationally in those months before Prohibition is a story well worth telling – and that’s even without mixing in the dramatic detail that crucial decisions were supposedly being made by a President of the United States who was only dimly aware of current events, having just suffered a massive stroke. But strangely, I can’t find a single book (much less an internet resource) that gives this tale its due. Prohibition authors waste little ink on everything between Congress proposing the Eighteenth Amendment and the dawn of the bootleggers; Woodrow Wilson biographers focus on the stroke and his obsession with having the U.S. join the League of Nations.

Read the old newspapers, however, and find this stumbling march towards Prohibition was told in screaming headlines, making it one of the top news stories in the year following Germany’s surrender.

Another excuse for writers avoiding these doings is because there are so many entangled parts that it can leave you cross-eyed trying to sort out what’s what. To assist Gentle Reader (and myself) a timeline is provided below which tracks the key moments in the story. Surely it will be a valuable aid to plagiarizing students for years to come.

And finally (before rejoining our show already in progress), this article is part of a series on the 1920s culture wars, an era with numerous parallels to America today. While this chapter covers the launch of Prohibition, the bigger theme is how our nation became so completely polarized over this single issue.

Just as WWI was ending, Californians voted on whether they wanted to go to war with their neighbors.

Voters were surely giddy when they went to the polls on November 5, 1918; every day brought more good news from the war front. German soldiers were surrendering en masse and their sailors were mutinying on the battleships. Terms for an armistice were finished and waiting for Berlin to sign. In a mere eight days The Great War was about to become history.

On the Californian ballot, however, were two propositions which supporters promised would “shorten the war and save untold blood and treasure.” Neither actually had anything to do with the war effort and only showed how those yearning for Prohibition had become jihadists for the cause.

Prop. 22 banned all manufacture, import or sale of intoxicating liquor, thus creating “bone-dry” Prohibition. But that wasn’t all; it imposed draconian punishments on anyone who broke the law – $25 and 25 days in jail for first time offenders, cranked up to $100/100 days for third and subsequent offenses.

Prop. 1 closed all the saloons – so you’d think all the teetotalers who had long called themselves anti-saloon crusaders would heartily vote in favor. Wrong! To the bone-dry moralists it was a stalking horse because it allowed alcohol to stay legal. Sans saloons, drinks could still be served in restaurants, cafes, hotels and other places where it “affects the women and boys and girls as well” [emphasis theirs]. The expensive quarter-page ad seen at right appeared in the Press Democrat and many other newspapers statewide.

Prop. 1 closed all the saloons – so you’d think all the teetotalers who had long called themselves anti-saloon crusaders would heartily vote in favor. Wrong! To the bone-dry moralists it was a stalking horse because it allowed alcohol to stay legal. Sans saloons, drinks could still be served in restaurants, cafes, hotels and other places where it “affects the women and boys and girls as well” [emphasis theirs]. The expensive quarter-page ad seen at right appeared in the Press Democrat and many other newspapers statewide.

Both failed to pass, although Prop. 1 came closest. In Sonoma and Napa counties Prop. 22 lost by about 16 points and nearly twice that in San Francisco. Yet in Los Angeles county and all the other counties nearby, harsh Prop. 22 won – sometimes by almost 3 to 1 margins – and they also generally voted with the dead-enders who wanted to wipe out all alcohol everywhere by voting against Prop. 1, which didn’t grant the purists everything they wanted.

There’s your snapshot of California prior to national Prohibition’s final sprint to the finish line. The state was culturally divided between the north and south, with Los Angeles and San Francisco being the two poles. In the 1920s LA was “the promised city for white Protestant America,” as historian Kevin Starr put it, “prudish, smug and chemically pure.”1 Overwhelmingly Anglo-American, no other ethnic group even topped five percent, including Hispanics. By contrast, one in five San Franciscans was foreign-born, mostly German, Italian and Irish – cultures which certainly did not shun drinking – and the greater Bay Area similarly reflected a diversity which looked a lot more like Europe than the WASP-y Southland.

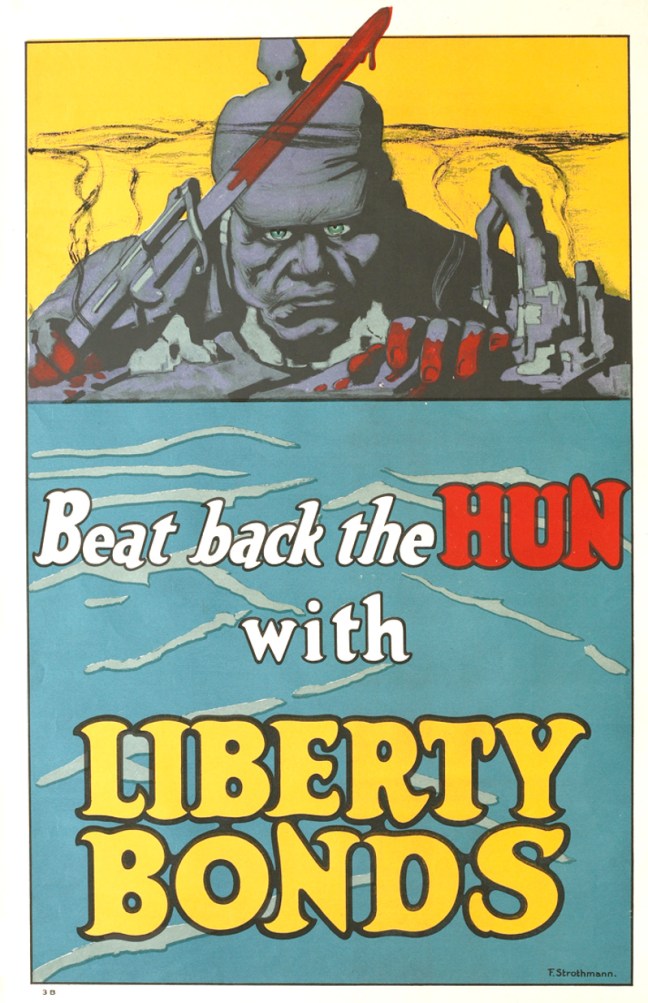

California was unusual in having such a strong geographic split over prohibition; in the rest of the country it was mainly a city/country divide. Dry advocates were mostly rural, anti-immigrant and conservative, while the Wet faction was clustered in liberal multi-ethnic towns and cities with factories and working class jobs. Both sides shared the hyper-patriotism surrounding WWI during 1917-1918 – which the bone-dry crusaders tried to exploit by casting anything to do with alcohol as being harmful to the war effort and un-American (see the previous article, “THE MADNESS OF 1918“).

Getting those propositions on the statewide ballot was a major accomplishment of the prohibition movement. A decade or so earlier, it only consisted of scattered righteous bullies trying to intimidate local governments into restricting saloons – how that played out in Santa Rosa was discussed in an earlier article. By 1918 they had become a force to recken with, thanks to the money and political heft of the Anti-Saloon League as well as their lineup of celebrity speakers – among them preacher Billy Sunday and conservative Democrat William Jennings Bryan). They were still righteous bullies, but now they had clout nationwide and were prepped to purge America clean.

| – | – |

|

Here’s the cheatsheet on Prohibition: The 18th Amendment banned “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors,” but not drinking alcohol, buying it or making it yourself. It also said nothing about how it was to be enforced. Months after it was ratified by the states, the Volstead Act (PDF) defined what “intoxicating” meant, which exceptions were allowed and put the IRS in charge of enforcement. The Wartime Prohibition Act was passed into law immediately after the war had ended. It was entirely separate from the 18th Amendment and had no purpose other than forcing prohibition upon the nation ahead of the Amendment’s start date.

The Eighteenth Amendment was really, really close to being ratified when President Wilson addressed Congress on Nov. 11, 1918 with the message, “the war thus comes to an end” – yet still he signed the Wartime Prohibition Act ten days later. It was supposed to apply only until “the conclusion of the present war and thereafter until the termination of demobilization… as proclaimed by the President.”2

The Wartime Prohibition Act was both mean-spirited and a dirty political trick. The Senate and House had bitterly hashed out the language for the Eighteenth Amendment to include a year’s grace before it was enacted, which would allow the alcohol industry to wind down without hardship. As it wasn’t yet ratified, no one yet knew when the countdown would start – but this new law broke the deal by declaring Prohibition would begin on July 1, 1919, come what may. It also put Wilson and his Democratic Party in a sticky position. The Democrats then were an uneasy alliance of “Wets” (mostly northeastern cities) and “Drys” (old Confederacy). By signing the bill which included the Wartime Prohibition Act, he risked pissing off much of the party’s political base. Wilson would spend much of the rest of his presidency trying to undo that.

LEFT: Wartime Prohibition Act ad appeared in the Press Democrat, July 23, 1918

LEFT: Wartime Prohibition Act ad appeared in the Press Democrat, July 23, 1918

But it would have been difficult for Wilson to veto the Act – although it’s said he signed it reluctantly – because it was actually a rider to an important agricultural bill. Also, Wilson personally wanted no truck with the prohibitionists, both due to his disposition and because they tried to bully him during his 1912 run for the White House.

A few months earlier the Sonoma County Farm Bureau had sent a letter to the White House pleading for Wilson to not sign the Act into law. The letter included valuable figures; there were 20,000 acres of wine grapes in the county and passage would “mean economic ruin to hundreds of families in Sonoma county, whose sons are now offering themselves for the supreme sacrifice…immediate prohibition will mean the loss of $4,000,000 this year to the producers of Sonoma county. Obviously this loss will seriously impair the ability of the banks of the county to meet their quota of Liberty Bonds, War Savings Stamps…”

It was soon after New Years’ 1919 when the Prohibition countdown began, after Nebraska became the 36th state to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment. But what was it, really? A toothless, symbolic nod to morality or a law greatly expanding police powers? Until the Volstead bill came along six months later, everyone seemed to have their own ideas.

While that pot was simmering, provisions in the Wartime Prohibition Act began to kick in. First came the May 1 ban on using any kind of foodstuff in the making of boozy beverages. This had little immediate impact as the 1919 grape harvest was months away and breweries already had been shut down the previous year as businesses non-essential to the war effort (MORE).

But shortly ahead was the July 1 start of bone-dry prohibition, which President Wilson wanted to squelch by having Congress amend or repeal the Wartime Prohibition Act. Still in Paris for the Treaty of Versailles negotiations, he sent a message on May 20 to Capitol Hill: “The demobilization of the military forces of the country has progressed to such a point that it seems to me entirely safe now to remove the ban upon the manufacture and sale of wines and beers…”

When Congress ignored him, Wilson sought to abort the Act by having demobilization declared complete. Just days before the Act’s prohibition was to start, Wilson was told by his secretary (Chief of Staff, today) that “best opinion says” the War Department was to announce demobilization by August 1, so he should be able to suspend the ban on wine and beer at that time. Sorry, the Attorney General cabled Wilson the same day; there would be no imminent demobilization because a million men were still in uniform under the war emergency call up.

In the last days of June, drinkers in Sonoma county and elsewhere were beset by panic. The Press Democrat reported all wineries with retail stores were mobbed; “the rush of this week is beating records. People are buying a supply to take into their homes so as to have it there for their own use. The supplies being laid in run all the way from two gallons to a hundred and even a larger quantity.” The owner of a liquor store told the PD that his shelves would be empty before the deadline.

As the nation braced for impact of total prohibition, this happened on June 30: The Department of Justice completely reversed its position and announced it would not enforce the Act’s ban on the sale of beer. Why? Because there was a pending court decision on whether “near beer” could be considered intoxicating.3

This development flung all the cards into the air once again. If the Wartime Prohibition Act’s definition of intoxicating was in question, then so was the very legality of the Act. And if the federal government wasn’t going to enforce it, then what laws regarding alcohol applied? Breweries reopened quickly and started making light beer, which was legal under the laws written in 1917. Should saloons still close? The Justice Dept. threatened they could be prosecuted retroactively if the Act was upheld in court. All closed in Petaluma; most in Santa Rosa apparently didn’t, as the City Council declared they would continue to accept the quarterly payments for liquor licenses – but no actual licenses would be issued. The situation was nuts.

Keep in mind all of this chaos surrounds just the Wartime Prohibition Act – a set of laws balancing on the fiction that WWI was still underway, although it had actually ended eight months prior. Eighteenth Amendment prohibition was still on the horizon for the new year, but the Drys in Congress were determined to keep the Act in place until that moment. “To repeal war-time prohibition now is like giving a half-cured drug fiend opium for a few months,” said Kansas GOP Rep. Little. When the Act was sent to the Supreme Court to settle its constitutionality, the House passed the most onerous bill yet, restricting alcohol under the Act to 0.5 percent. Like our little cartoon bear seen at the top, reprieve was only momentary – there was always another axe waiting to fall.

During those summer months the Volstead rules were under debate and rumors flew. All liquor advertising would have to be removed or painted over (true); people could be arrested for telling someone where they could get a drink (false). The government could take away your home if you had liquor on the premises (false); the government could seize your car or truck if liquor was found in it (true).

Wine makers in Sonoma and Napa were particularly susceptible to rumors because the grape harvest was approaching and they desperately wanted good news. The PD reprinted an item from the St. Helena Star squashing a report that the ban on wine would be lifted just in time for the crews to begin picking. Nope. But there was actual good news when the first Volstead details were announced in September; there would be exemptions for the making of wine for sacramental and medicinal purposes, and Kanaye Nagasawa promptly announced the Fountaingrove winery was “going ahead with plans to pick the grapes and make them into wine, just as though there was no such thing as a prohibition law,” according to the PD.

That happened in September while President Wilson was spending a month on a private train barnstorming around the country, trying to drum up public support for the Senate to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. His tour was cut short when the President suffered a mini-stroke, which was not revealed to the public. Back in the White House on October 2, Wilson had a major stroke which left him partially paralyzed. This too was kept secret from the public, even the Congress and Cabinet members. For the remaining 17 months of his presidency, we now know crucial decisions for the country were being made by a troika consisting of his secretary, doctor, and primarily his wife, Edith.

During those fragile early days after the stroke, Congress sent him the Volstead Act to sign. While the press had hashed over most of its rules and regs under the upcoming enactment of the 18th Amendment, the Act also contained an ugly surprise – immediate enforcement of the Wartime Prohibition Act. Although real Prohibition was only three months away, the Drys wanted to give everyone else in the country this one last poke in the eye.

The White House vetoed the act, pointing out there was a distinct difference between the permanent constitutional amendment and that temporary wartime measure, which Wilson had asked Congress to cancel a few months earlier.4 The veto message was written in the first person and signed by the president, although it’s now believed he had no role at all in writing it and probably knew nothing about what was going on with the issue, so carefully did Edith shield him from any upsetting news.5

The Act went back to the House, where the Dry “steam roller” (as the NY Times put it) rushed through a veto override after it was noticed a number of Wet congressmen coincidentally were absent that afternoon. After their defeat, historian Vivienne Sosnowski wrote, “…the anti-Prohibitionists stormed out of the House as soon as the vote was counted, feeling defrauded by what seemed to them to be an illegitimate and essentially malicious act: They felt like stunned victims of a savage ambush.”6 The Senate joined to override Wilson’s veto the next day and the Volstead Act was now law. America was officially bone dry.

Before the Senate actually voted, however, the White House announced it would annul the Wartime Prohibition Act just as soon as the Senate ratified the Treaty of Versailles in the near future. The peace treaty would have given Wilson the power to do that, as the veto message specifically proclaimed demobilization was complete. The Press Democrat jumped at this lifeline:

What a lift of the “wet ban” would have accomplished is unclear, as the Volstead Act was now law and it had immediately flicked on the switch for prohibition (note the “Bone Dry America” deck below the banner hed). With such little time remaining before the Jan. 20 start of Prohibition, it could only have sown confusion. I believe, however, that the White House announcement was a pivotal moment in the history of our nation – and maybe even the world.

Less than a month later, the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, and with it, U.S. membership in the League of Nations. Historians agree America’s failure to join the League left it weak and rudderless during the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy, key developments leading to WWII. But reasons why the Senate refused to ratify the treaty are less clear.

Gather a group of eminent scholars on American history in a room (tip: They’ll all be underpaid by their universities, so at least offer nice canapés). Some will argue it was because Congress hated peace terms in the treaty. Some will argue it was because Congress hated the League of Nations charter. It was because the nation was in the mood for isolationism. It was because Republicans were miffed at Wilson for not including them in treaty diplomacy. It was because Wilson’s stroke (which no one knew about at the time, remember) had left him disinhibited and implacably unwilling to negotiate with Congress. It was because there was a bipartisan faction called the “irreconcilables” who thought the whole thing just stunk. And you know what? ALL of those scholars are right. There were multiple reasons why the Treaty of Versailles failed to get a two-thirds Senate vote.

But go back and read the newspapers at the end of October 1919. The pressing concern was this: Will the Drys demand Congress oppose the treaty because passage might mean Wilson lifting the “wet ban?”

Oh, no, said the Anti-Saloon League (see transcript below), we wouldn’t monkeywrench something like that – and besides, wartime prohibition would continue until another treaty was eventually signed with Austria-Hungary, they said, both moving the goalposts several years further away and revealing that yes, the League took Versailles ratification as a serious threat to prohibition.

This was a turning point in America’s history, but on the eve of that critically important Senate vote, our political system was paralyzed over anything which might possibly touch the (increasingly irrelevant) Wartime Prohibition Act.

Soon it would be 1920, which would not only be the birth of Prohibition, but also the death of the Progressive era in America. It was to be a major election year and Wilson would be a lame duck even if he had been capable of leadership; in the next Congress, two out of three representatives would be from a Dry district. Appeasing those voters was paramount, and best to be on the record voting down the Treaty of Versailles, even though there was only a possibility it might have given the Wets a brief and meaningless win.

Thus here’s the obl. Believe-it-or-Not! punchline to our story: Hey, we may have lost the chance to avoid World War II, but at least we completely eliminated the possibility of some schlubs drinking a lite beer for a few weeks around New Year’s 1920.

As 1919 came to a close, the tribe of the Drys were jubilant, not just for the banishment of alcohol, but for victory in their culture war – in modern parlance, they were satisfied that they were now “owning the libs.” New York Congressman Richard F. McKiniry said at the time it was mainly about the rural areas spitefully “inflicting this sumptuary prohibition legislation upon the great cities. It preserves their cider and destroys the city workers’ beer.”

For them Prohibition was an end in itself – but other Drys had religious fervours that Prohibition was to lead America into becoming their New Jerusalem. I’ll give the last word to Daniel Okrent, author of the best modern book on Prohibition: 7

…by the time the Volstead Act became law, the Drys had become giddy in their political dominance and confident they would retain power sufficient to correct any errors or omissions. They believed that their cause had been sanctified by the long, long march to ratification, that it had truly been a people’s movement every bit as glorious as any other in the nation’s history…Over the next decade, the product of eighty years of marching, praying, arm-twisting, vote trading, and law drafting would be subjected to a plague of trials, among them hypocrisy, greed, murderous criminality, official corruption, and the unreformable impulses of human desire. Another way of saying it (and it was said often in the 1920s): the Drys had their law, and the Wets would have their liquor. |

1 Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920’s by Kevin Starr, 1990, summary of chapter 6, “The People of the City: Oligarchs, Babbitts, and Folks”. The “chemically pure” remark comes from a famous 1913 essay, “Los Angeles: The Chemically Pure” which bemoaned that LA had been taken over by intolerant moral purists from the Midwest with a “frenzy for virtue.” |

2 Misunderstandings about the so-called Wartime Prohibition Act are common and it’s easy to see why; even with modern internet search tools, information about it is damned hard to find. That title wasn’t used very often at the time (and usually spelled “War-Time” or “War Time” when it did appear), and was frequently just called the “Norris Amendment” because the rider was added by Senator George Norris, a progressive Republican from Nebraska who led that party’s dry faction in the Senate. It is also often misstated that it was part of the “Emergency Agricultural Appropriations” bill, but it was actually attached to the Food Production Act for 1919 (H. R. 11945). Some authors further confuse it with the 1917 Food and Fuel Control Act, AKA the Lever Food Act, which placed restrictions on industries deemed nonessential to the war effort. When Wilson signed that earlier bill on August 10, 1917, he issued a further proclamation cutting back brewery output by 30 percent. For primary sources and more details, see this excellent study produced by the Carnegie Endowment in 1919. |

3 “Near beer” had been a common term since at least 1909 and meant 2.75 percent alcohol by weight – or 3.4 percent by volume, which is the way we usually measure alcohol content today. This was the maximum content for beer as set by the 1917 Lever Food Control Act. Today’s light beers are about 4.1 percent ABV. |

4 To the House of Representatives: I am returning without my signature H. R. 6810…The subject matter treated in this measure deals with two distinct phases of the prohibition legislation. One part of the Act under consideration seeks to enforce war time prohibition…which was passed by reason of the emergencies of the war and whose objects have been satisfied in the demobilization of the army and navy and whose repeal I have already sought at the hands of Congress…it will not be difficult for Congress in considering this important matter to separated these two questions and effectively to legislate regarding them; making the proper distinction between temporary causes which arose out of war time emergencies and those like the constitutional amendment… |

5 Woodrow Wilson: A Biography by John Milton Cooper, 2009; pg. 415 |

6 When the Rivers Ran Red: An Amazing Story of Courage and Triumph in America’s Wine Country by Vivienne Sosnowski, 2009; pg. 45 |

7 Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition by Daniel Okrent, 2010; pg. 114 |

SCORES IN RUSH TO LAY IN WINE

Unheard of Rush at Wineries in the County Where Wine Can Be Purchased at the Present Time in View of Approach of July First.It might be said that there is a great rush on at every winery in Sonoma county where wine can be purchased these days in view of the approach of July 1.

This has been the case for weeks past, but the rush of this week is beating records. People are buying a supply to take into their homes so as to have it there for their own use. The supplies being laid in run all the way from two gallons to a hundred and even a larger quantity.

It is said that scores of people who openly state they have never drank wine before that they are not in favor of stopping the industry and are not going to let the opportunity go by to have a taste while tasting remains.

A well known winemaker in town yesterday stated that he never saw such a rush as had been on at his place this week by people calling and buying wine to take to their homes. Among them were people, he said, who were not in the habit of drinking themselves, but wanted to see their friends enjoy a glass of wine even after the war-time prohibition became effective, when they are their guests. Just three days more of a rush, if nobody rules to the contrary, some homes are going to be very popular after July 1.

– Press Democrat, June 28 1919

OLD JOHN GIVEN MERRY OLD RUN

Thousands of Dollars Worth of Liquors Were Sold to People to Take to Their Homes by the Various Establishments Here SaturdayIn establishments where liquors are sold in this city there was the biggest rush of years on Saturday.

Men and women, in view of the “bone dry” law becoming effective so soon, were laying in a little stock, many of them for medicinal purposes.

In one establishment before seven o’clock at night, it was stated over one thousand dollars’ worth of liquor had been sold at retail in bottles and in dimis. or in cases since the store opened in the morning and the proprietor stated that he would be all sold out before the time for closing came Monday night.

The rush continued at the wineries and hundreds of customers were purchasers of a little wine or sherry to tide them over for a time and allow them to gradually taper off into the enjoyment of some other beverage.

Old John was given a merry old run here Saturday. There is one more day and night left for the saloons.

– Press Democrat, June 29 1919

NAGASAWA BACK FROM EAST TO MAKE WINE FROM CROPS

Japanese Vineyardist Hopes for “Reprieve,” But Will Use Output for Medicinal and Sacramental Purposes If the Drouth Continues Unabated.Confidence that the grape crop and vintage of 1919 will be disposed of without any loss is displayed by Kanaye Nagasawa, owner of Fountaingrove, one of the largest vineyards and wineries in Sonoma county, and Nagasawa is going ahead with plans to pick the grapes and make them into wine, just as though there was no such thing as a prohibition law.

[..]

– Press Democrat, September 4 1919

GRAPE AND WINE SITUATION IN NAPA COUNTY DESCRIBED

The following article regarding the grape and wine situation from the last issue of the St. Helena Star, will be read here with interest:

Winemakers and grapegrowers are still up in the air and don’t know just where they will land. There seems, however, to be brighter prospects than before that the entire crop of grapes will be cared for.

Wine making in the old way, for beverage purposes, seems to be a thing of the past, at least for this year, as the law does not permit its manufacture for beverage purposes, and notwithstanding rumors there is no evidence at hand that the ban will be raised in time for this vintage, if at all.

ALL KINDS OF RUMORS

All kinds of rumors are afloat about raising the ban on wine making, and all such merely confuse both winemakers and the grapegrowers. One rumor reached St. Helena Wednesday coming indirectly from the office of the Collector of Internal Revenue in Los Angeles that the ban on winemaking would be raised on September 25. Immediately the Star wired the collector for verification and authenticity of the report and received the following reply:

Los Angeles, September 4, 1919.

St. Helena Star. St. Helena. Cal.:

Statement erroneous. Absolutely no information at this office regarding amendment of present regulations concerning winemaking.

John H. Carter. Collector.Another report is that demobilization will be declared on November 15, but the grapes will either be harvested or will have perished on the vines by that date. The thing for grapegrowers to do is not to pay any attention to rumors.

[..]

– Press Democrat, September 12 1919

PROHIBITIONISTS NOT TO INTERFERE IN PEACE SIGNING

Associated PressWASHINGTON, Oct. 28.-—Senate parliamentarians of years’ experience said that although the question never had been raised before, they believed the prohibition enforcement bill became law from the moment of the Senate action in overriding the veto at 3:40 o’clock today.

Prohibition forces in and out of the Senate will not attempt to delay ratification of the peace treaty because of the White House announcement that wartime prohibition will end with formal ratification of the pact, officers of the Anti-Saloon League announced.

E. C. Dinwiddie, in charge of the Anti-Saloon League fight before Congress, said dry forces adhered to the belief that wartime prohibition would stand until the Senate had ratified the Austrian treaty, but regardless of that “the league will not attempt to block consideration of the treaty.”

– Press Democrat, October 29 1919