At the very top of Mount St. Helena is a marker commemorating the founding of Fort Ross in 1812. Why there is a sign concerning a place 32 miles away is not explained, and should anyone examine the monument further, a deeper meta-weirdness is revealed: It’s really a sign commemorating an earlier sign.

After slogging up that steep and unforgiving trail for about three hours, a weary hiker also gets a mental workout in trying to grasp what the monument actually stated – which was that on this spot in 1912, a group of descendants of famous people put up this sign because on this spot there used to be a sign reading, ‘two Russians were at this spot in 1841’ which was removed from this spot in 1853.

Whew.

Intrigued but hopelessly confused, our intrepid hiker pulls a mobile phone from his/her backpack, certain that the cell towers also at the summit will provide a blistering signal (and hopefully not enough microwave energy to cause actual blistering).

From the internet, our visitor learns the monument actually describes how the mountain was named – which is a bit odd considering “Helena” does not appear anywhere on the marker. To paraphrase the top three results currently found by Google: During the 18th century Baron Count Rotchef visited Fortress Ross with his beautiful young wife Princess Helena, who was held in high regard by her people because. Helena joined a Russian survey party who ascended the peak in 1841, where they left a copper plate inscribed with her name and the date.

And that wasn’t all; had our hiker Googled a bit further, (s)he would have discovered that as the Russians came down from the mountain, an Indian chief tried to kidnap the princess.

As Gentle Reader can surely guess, there’s a whole lot of hokum to this story – problems that began even before the strange marker-about-a-marker was placed up there in 1912. It’s been like a very old and pretty tangled ball of yarn that everyone likes to handle but no one bothers to unwind and fix.

Here is what we know to be facts: Some Russians actually climbed the mountain in 1841 and left a copper plate there. There really was a “Princess Helena” around here at the time. End of facts.

We don’t know who the “Helena” was in the name, if the Russian named it before the day of their visit, or even that the Russians named it at all. Alexander Rotchev – the last administrator of Fort Ross and Helena’s husband – did not mention the mountain at all in his memoirs.1

The only written evidence the Russians were on the mountain at all comes from Ilya Voznesensky, who was sent to the Russian colonies by the Imperial Academy of Sciences to document the territory. All he states in his travel journal is that on June 16, 1841 he climbed “one of the highest mountains on whose summit no one had then yet been.”2

His journal didn’t mention the plaque or that anyone else was with him, but there were two names scratched into the metal: His and Yegor Chernykh, an agronomist who was at Ft. Ross to train the colonists in better farming techniques. Together they traveled widely in the area, visiting Pomo villages and mapping the Russian River as far as modern Healdsburg.

And, of course, there’s the copper plaque, which we know was actually on the mountain from a sighting of it in 1851. A letter to the Daily Alta California (transcribed below) described how nine men climbed the mountain and found a copper sheet about three feet square, “upon which was engraved hieroglyphics not by us decipherable.” The group – none of whom had obviously seen Cyrillic – wondered if it could be Aztec, or the “handiwork of the Mongolian race as far back as the time of Confucius.” The (un)helpful editor of the newspaper explained they saw the “latitude, longitude and altitude of the mountain, as ascertained by a party of Russian navigators,” and that “it is said that similar copper-plates were placed on several other high peaks in the vicinity of the coast.”

By 1866 the sign was gone. Another correspondent to the Alta wrote, “some years ago a fool or vagabond vandal removed an inscription that had been left on the summit” and the next year another informed the paper, “at the summit I found the post on which the Russians affixed the copper plate which was taken down several years ago by some persons who gave it to the State Geological Survey.”

And that’s the last we hear from anyone who had first-hand knowledge of anything related to the sign. Notice, too, that no one had yet claimed the Russian visit or the copper sign had anything to do with naming the mountain “Helena.” That all changed forty years after the Russians had gone away.

(By the way: The village of St. Helena was given that name in 1855 because the local chapter of the Sons of Temperance men’s group already called itself the “St. Helena Division.” As their Division names usually reflected a town or landmark, it’s safe to presume the mountain was commonly called Mt. St. Helena by then.)

From what I can find, the 1880 Sonoma county history was the first place the princess-namesake story shows up. The claim appears in a lengthy quote from Charles Mitchell Grant, an explorer and member of the Royal Geographical Society who then lived in the Bay Area. He had no expertise about the Russian colony at Fort Ross but twenty years earlier he had bummed around China and Russia, so apparently that made him an authority on all things Russian.3

Besides Grant’s matter-of-fact claim that the mountain was named for the administrator’s lovely wife, he also dishes up the first printed version of the kidnapping story. Grant wrote, “The beauty of this lady excited so ardent a passion in the heart of Prince Solano, chief of all the Indians around Sonoma, that he formed a plan to capture, by force or stratagem, the object of his love…”

That’s a paraphrase from a story in General Vallejo’s unpublished memoir, where supposedly Vallejo’s key Indian ally, Chief Solano (Suisun tribal leader Sem-Yeto), meets Princess Helena while she and her husband are visiting Vallejo in Sonoma. That night Solano tells Vallejo he planned to abduct her and asks for Vallejo’s approval. Vallejo is horrified and shames Solano into abandoning the notion. A translation of the full tale is found in the footnote.4

This isn’t the place to really dive into a full analysis of the story, but I’ll say only I don’t believe it happened as Vallejo described. It fits too perfectly with the school of humor which could be called the “wise captain and the fool,” where a stupid person is the butt of the joke because he must be instructed on how to behave properly. Vignettes with that theme were popular in newspaper entertainment pages during the 19th and early 20th centuries, usually with an underlying racist message – “those people” have strange ideas and aren’t as good as the rest of us.

The less titillating info in the 1880 history was further news about the Russian plaque: “In the year 1853 this plate was discovered by Dr. T. A. Hylton, and a copy of it preserved by Mrs. H. L. Weston of Petaluma, by whose courtesy were are enabled to reproduce it. The metal slab is octagonal in shape, and bears the following words in Russian: RUSSIANS, 1841 E. L. VOZNISENSKI iii, E. L. CHERNICH”.

Unfortunately, that terse description left unexplained whether Dr. Hylton took it away with him or just traced over what was written. Nor was it explained how large the original was. It was later stated the paper copy given to Mrs. Weston was only about five inches across and shaped like an octagon.5

If nothing more was written of the tale of the Russians on Mt. St. Helena, it would have ended up as an obscure anecdote to the history of Fort Ross. But starting in the early Twentieth Century, the story was transformed into a myth about the mountain of the beautiful princess and her thwarted Indian paramour. And all that is thanks to Miss Honoria R. P. Tuomey.

Honoria Tuomey was born in 1866 at her family’s ranch off of Coleman Valley Road. Most of her life she was a grammar school teacher and principal in West County; the Sonoma County Museum has a box of her memorabilia which is greatly filled with yellowed photos of her posing with farmkids in front of one-room schoolhouses. She started by writing poetry and had a lengthy profile of Luther Burbank printed as a Sunday feature in a 1903 Los Angeles paper; Gaye LeBaron wrote a 1990 profile of Tuomey worth reading for general background on her life and works.

(RIGHT: Honoria Tuomey, 1912. Photo courtesy Sonoma County Museum)

Tuomey is best known today for her two-volume Sonoma county history published in 1926, and although LeBaron’s remarks about those books might seem unkind, they really are worthless except for the biographies that makes up the entire second volume. The first book is interjected with a mish-mash of random facts, dubious hand-me-down stories and bits of melodramatic narrative – complete with made-up dialog. Parts are even irrelevant to Sonoma county history; while there’s hardly a word about the Chinese there is a full chapter on “the French in California.” Overall it’s even worse than Tom Gregory’s 1911 history, and I suspect some of his research came from tall tales he swept up in Santa Rosa barrooms.

Honoria’s history focused on West County – which isn’t at all a bad thing, as all the other local histories dwelled heavily on Petaluma, Santa Rosa and Sonoma. Still, LeBaron quipped, “It weighted so heavily toward the coast that it threatened to tip the whole county into the Pacific Ocean.” So it’s not surprising Tuomey’s book contains much on the history of the Russians and Fort Ross, with four chapters on it – far more coverage than she gave the Bear Flag Revolt and founding of the state.

Her passion for the Russian colony extended to the legend of the lost marker on Mt. St. Helena, twice climbing the mountain in search of clues, as she later revealed in an article. “For several years I had read and researched, and interviewed old settlers, and all to no avail so far as obtaining a clue either to the existence and whereabouts of the plate, or its possible location on the mountain.”6

Tuomey’s quest for the marker ended when she came across an old pamphlet mentioning the business about Dr. Hylton and Mrs. Weston. That she didn’t realize the same info could be found in Sonoma and Napa county histories published in the early 1880s says lots about her scholarship.

With an eye on placing a replica on the very same rock to mark the centennial of Fort Ross, Honoria got busy. She asked the Kinslow Brothers – a company more accustomed to carving tombstones – to donate a marble plaque, with this engraved in the center: “RESTORED JUNE 1912 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDING OF FORT ROSS.” She asked a Santa Rosa jeweler to engrave three copper plaques: a reproduction of the original Russian, another with an English translation, and the largest of all with the names of some of Sonoma county’s famed Mexican and American families. And she trekked up the mountain for a third time by herself to make sure she knew the proper place for all this to go. Say what you want about Honoria Tuomey, but she had remarkable dedication to her mission; she was around 45 years old while doing all this.

And thus on the 20th of June, 1912, Honoria led a small army of celebrants climbing up the mountain. At the summit the American flag was raised, messages and poems were read and speeches delivered. There was a stirring benediction and everyone sang “America” at the end. I have absolutely no doubt this was the happiest moment of her life.

|

| Honoria Tuomey at the dedication of the Mt. St. Helena plaque. 1912. Photo courtesy Sonoma County Museum |

A few weeks later the San Francisco Call presented a Sunday feature on the ceremony with an article by Tuomey. Per the Russian visit in 1841, she wrote:

…The complete personnel of this doughty expedition is not revealed in any records of history, but besides Doctor Wosnesenski and his friend, E. I. Tschernech, it included the handsome young Helena, Princess de Gagarine, wife of Alexander Rotcheff, the last governor of Ross settlement, and John Edward Mcintosh, grantee in 1837 by General M. G. Vallejo of the rancho Estero Americano to block Russian encroachments inland; also a small guard of soldiers. There were some lively thrills on that trip of some forty miles, not the weakest being occasioned by the attempt of old Chief Solano to abduct the princess. Up the rough, almost perpendicular side of the mountain the party mounted to the summit of the north peak, the highest point of elevation. Here upon a flat rock the copper plate was spiked and additional blocks were fitted to form a cairn. While the others knelt, the princess, raising her right hand, proclaimed the name of the mountain forever “Helena” in honor of her royal mistress and namesake, Helena, empress of Russia… |

In this new, never-before-told version, it’s getting pretty crowded up there at the summit, what with the princess, the soldiers and all. But thank goodness an armed escort was along on this trip because an Indian chief tried to snatch the princess. It’s all a perfect example of classic Honoria Tuomey: 10 percent was probably true, 10 percent was iffy, 10 percent was clearly junk and the rest was stuff she heard somewhere and thought it sounded good.

It would be easy to presume she just made most of that up, but thanks to her 1924 article, we learn her embroidered details came from Dan Patton, who ran the Mount Saint Helena Inn (7 miles from Calistoga on highway 29) back when Tuomey was on the hunt for all things Russian.

It seems Patton was pals with William Boggs, a notable figure in Sonoma and Napa counties in the decades after statehood. Boggs had known a guy (no name given) who supposedly was one of the soldiers in that pack of Russians who went up the mountain in 1841; when the rest of his countrymen abandoned Fort Ross and left for Alaska at the end of that year he was left behind for some reason. The Russian told the story to Boggs who told the story to Patton who told the story to Tuomey.

“Documentary evidence may not always be obtainable, may not exist,” she wrote, “but the free testimony of those who have lived and made history can be accepted, when known to have come down to us through veracious channels.” Dear Honoria; I know a few people who might disagree with you on that – namely every historian.

Tuomey had other novel and elaborate ideas about how the mountain came to named that won’t be detailed here. In a series of coincidences which Robert Ripley might have found hard to swallow, she believed it was independently christened “Saint Helena” three times – first by a Spanish friar, then by the Russians, and finally by Captain Stephen Smith of Bodega Bay.

Honoria R. P. Tuomey died in 1938. Besides the plaque on the mountain, she left hand-painted signs all over the county marking historic events – most (all?) are gone now, or stored away. But her real legacy is the unfortunate trail of misinformation about the Russian connection to Mt. St. Helena.

One afternoon I dived down the rabbit hole to see what people were writing about it since Honoria’s heyday. In travel guides, books, newspaper and magazine articles I found 27 new and unique details to the three Tuomey theories before I stopped counting. Some lowlights:

The princess on the mountain named it after her aunt, the empress of Russia (who wasn’t her aunt or named Helena); her arms were flung wide, Christlike, or she knelt in prayer as she named it after her patron saint; Russian sailors prayed or sang hymns. Another thread had Chief Solano and other Indians capturing the party at the base of Mt. St. Helena when Salvador Vallejo happened to come riding along to rescue them, or General Vallejo having to negotiate their release with the Vallejo silverware being Rotchev’s gift for saving his wife. The original plaque was given to the Society of California Pioneers museum in San Francisco by Dr. Hylton, where it was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake although it was never there.

Never, ever, is the simplest and most likely explanation discussed: That the “plaque” was possibly just the equivalent of 19th century grafitti – two guys taking a break after a long hike and scratching their names on a piece of scrap metal.

As of this writing (December, 2017) the park is closed because Mt. St. Helena burned in the Tubbs fire. I have been unable to reach anyone in the park service who can tell me whether the marker is still intact; the copper could have melted or the whole thing could have been run over by a big CalFire truck.

But if it’s really gone, let’s not rush to replace it – we don’t need to keep inspiring people to write phony history. Should the sign be indeed replaced, let’s at least offer an honest representation of what it said: “Russians Eli and George, June 1841.” And just leave it at that.

1 Most of Rotchev’s papers were destroyed in a 1974 fire, but in the Argus-Courier, October 12, 1963, there was a quote from a 1942 letter from Mrs. Harold H. Fisher: “Mr. Redionoff (chief of Slavic Divison, Library of Congress) wrote me that the A. G. Rotchev memoirs do not mention the mountain…” |

2 The odyssey of a Russian scientist: I.G. Voznesenskii in Alaska, California and Siberia 1839-1849 by Aleksandr Alekseev, 1987 |

3 An overview of Charles Mitchell Grant’s travels appeared in the Royal Geographical Society’s 1862 proceedings. Grant had only one leg and frequently had to travel in a cart when the only transport available was via camel or mule. |

4 When Senor Rotcheff…came to see me, he was accompanied by his wife, the Princess Elena, a very beautiful lady of twenty Aprils, who united to her other gifts an irresistible affability. The beauty of the governor’s wife made such a deep impression on the heart of Chief Solano that he conceived the project of stealing her. With this object he came to visit me very late at night and asked my consent to putting his plan into effect. The story horrified me, for if it should unfortunately be carried out my good name would suffer, for no one would be able to get it out of his head that my agent had acted on my account; and besides seeing the country involved in a war provoked by the same cause which actuated the siege of Troy, I, who had never hesitated at expense or trouble to please my visitors…would be stigmatized as the most disloyal being that the world had ever produced. It was necessary for me to assume all the authority that I knew how to assume on occasions that required it to make Solano understand that his life would hang in the balance if he should be so ill-advised as to attempt to break the rules of hospitality. My words produced a good effect, and that same night, repenting of his conduct, he went to Napa Valley, where I sent him to prevent him from compromising, under the impulse of his insane love, the harmony which it was so urgent for me to reestablish with my powerful neighbors…But, fearing that Solano might ambush them on the road, I went to escort my visitors to Bodega. (Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez translation as found in “Spanish Arcadia” by Sanchez, 1929) |

5Dr. Thomas A. Hylton was a Petaluma physician in the mid-1850s, and H. L. Weston was the publisher of the Petaluma Journal, having purchased it from Thomas L. Thompson in 1856. His wife was mentioned in 1868 for her skilled needlework for having crocheted portraits of famous men and even De Vinci’s Last Supper. Caroline died in 1909, having lived in Petaluma for 52 years, and Henry died in 1920. |

6 “Historic Mount Saint Helena” by Honoria Tuomey, California Historical Society Quarterly, July, 1924

|

|

| The reproduction plaque and English translation (Image: Wikipedia Commons) |

In The Presence Of Representatives Of The Sonoma Pioneer Families Of

General M. G. Vallejo – Senora M Lopez De Carillo

Captain Henry D. Fitch – Captain Stephen Smith

Jasper O’Farrell – C. Alexander

Donner Party – Bear Flag Party

And Of

The Native Sons Of The Golden West

The Spanish, British, Russian And Mexican Consuls At S. F.

Dr. T A Hylton Removed The Original Plate From This Rock

In May 1853 And Gave A Copy To H. L. Weston Who Has

Authorized Miss Honoria R. P. Toumey

To Make This Restoration

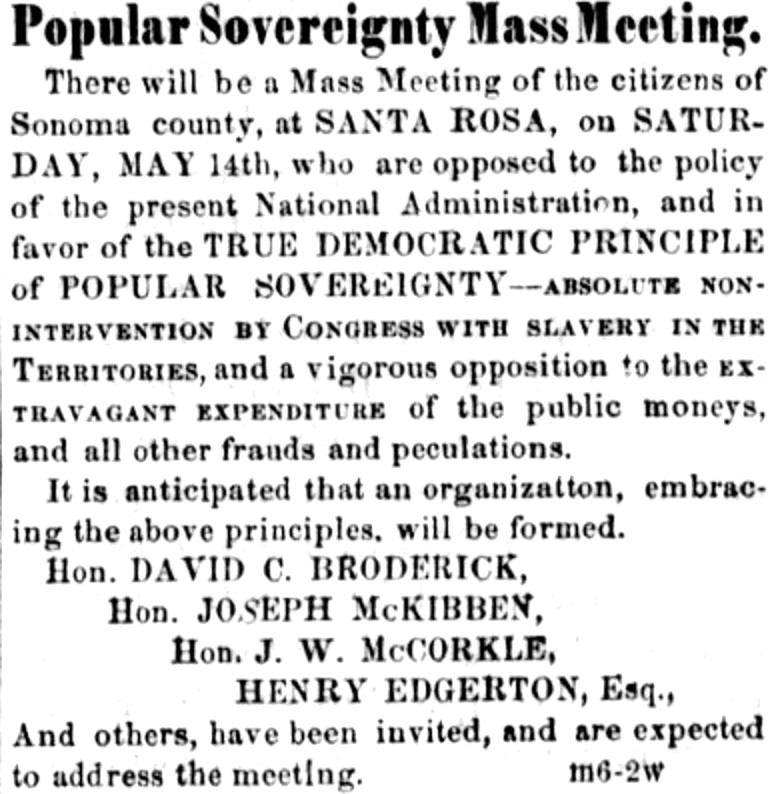

The Mysterious Copper Plate on the Top of St. Helena.

A correspondent of the Marysville Democrat writes as follows:

“Napa Valley is unquestionably one of the loveliest spots on this earth… At the upper end of the ralley rises St. Helena, an abrupt, lofty mountain — the highest peak north of the bay — upon the very highest point of which there rests, or did rest, a copper plate, the history of which is buried in the silent tomb of oblivion.

“As wonderful as that relic of by-gone ages is, I do not recollect ever having seen even a newspaper paragraph in relation to it. Eight years ago last July, three gentlemen from San Francisco, three from Sacramento city, two from Napa and myself, having heard of the existence of said plate, ascended that mountain’s rugged form and gratified as far as possible, our curiosity. It was indeed a wonder. The plate was thin, about three feet square, upon which was engraved hieroglyphics not by us decipherable, notwithstanding that our company, altogether, understood five different languages.

“While wondering over the defunct history of that old copper plate, we could not help speculating upon the probable race so advanced in the arts which could possibly have occupied this interesting country at so remote a period. Is it not possible that this continent mar have once been connected with the north-eastern coast of Asia? One might be led to look upon that valuable plate as a piece of handiwork of the Mongolian race as far back as the time of Confucius, were it not that the characters do not resemble their language.

“Again, it is not impossible that the original Aztec tribe, the founders of those splendid ruins of Yucatan, may have originated from the Caucasian stock, and gradually worked their way towards Bhering’s Straits [sic] down the continent, having temporarily occupied different portions of the now Alta California in the course of their gradual migration.”

The mysterious character alluded to in the above correspondence, are those of the latitude, longitude and altitude of the mountain, as ascertained by a party of Russian navigators, who made a hasty survey of the coast, when the Russians had possession of the coast near the mouth of Russian river, and expected to hold a large part of California. It is said that similar copper-plates were placed on several other high peaks in the vicinity of the coast.

– Daily Alta California, January 1 1860

Places of Note.

…To me, one of the most interesting points is Mt. St. Helena, not because of any peculiar natural attraction, but it haa bern consecrated by the footsteps of the great Humboldt, and I never look up to that dark mountain pile without feeling as if it had been rendered a sacred spot by the influence of such a presence. Some years ago a fool or vagabond vandal removed an inscription that had been left on the summit by that greatest of philosophers. It was a copper plate set in the rock, and was a valuable memento of long years of the past.

– Daily Alta California, August 30 1866

LETTER FROM CALISTOGA

…At the summit I found the post on which the Russians affixed the copper plate which was taken down several years ago by some persons who gave it to the State Geological Survey. It should be replaced with another plate containing a translation of its inscription…

– Daily Alta California, May 3 1867

ACROSS THE MAYACMAS.

…St. Helena, the highest and most shapely mountain in this lofty chain, is visible from base to crest, the line of light and shadow on its rugged slopes is so plainly marked, its clean-cut outline against the sky is so well defined that it is difficult to realize the intervening space of foot-hill, valley and wooded Slope, which makes up the foreground of this far-reaching and surprisingly beautiful landscape. This view of St. Helena, or at all events a similar one, doubtless, inspired the Russian naturalist Wossnessensky, who was the first to ascend it, and who named the mountain in honor of his sovereign, the Empress of Russia. He imbedded, in a rock on the summit a copper plate, to commemorate the event. Upon the plate was inscribed the date of the ascent, “June 12, 1841,” the name Wossnessonsky, and that of his companion, Techernich, and the word “Russians,” twice repeated in the Russian language and once in Latin. This plate was removed by some vandal and afterwards came into the possession of members of the so-called State Geological Survey, who probably took it out of the State where it has no local interest.

– Sonoma Democrat, May 28 1881

THE SHORT STORY CLUB HAS MEETING

Miss Honoria R. P. Tuomey read a charming description of the life and writings of Robert Louis Stevenson, having secured the local color for her sketch by a visit to his old camp on the southwest side of Mount St. Helena. It was here that he wrote “The Silverado Squatters.”

– Press Democrat, June 19 1910

RESTORATION ON ST. HELENA

HISTORIC PLATE TELLS OF RUSSIAN OCCUPATION

Old Spanish Families Represented at Notable Ceremonies on the Mountain’s Summit Thursday

On Thursday last, June 20th, the great Mount St. Helena was awakened from its sleep of age into a new historical life. Its rocky gorges, its thorn-brushed ridges and its lone wild peak away up against the blue sky, all rang with the echo of a Voice. It was the Voice of the age one hundred years distant from the white hand of the Czar of all the Russias. One hundred years away from the black bearded Muscovite who toiled and climbed from old Fort Ross by the Pacific, through primeval redwood forests o’er meadowlands deep grassed, but angered into life by the growl of the grizzly and the leap of the stag. On and on they came, those Russians of the frozen sea and the aurora land of ice. Wosnesenskl, the Third, Tschernech, and their beautiful princess, up and up the steep mountain side, scaling the cliffs and tearing their chaparal pathway to the wild, desolate peak of the great unnamed mountain.

The story is of June, but the pathway was as December, wild in its every setting. The sacred burden of their pilgrimage was a rudely carved copper plate bearing the inscription

RUSSIANS

P. L. WOSNESENSKL III

E. I. Tschernech

RUSSIANS

This in the rude character lettering of the kingdom of the Czar. This they bolted to a rock of the peak in June of 1841, and as they stood on this great mount “Helena.” Later, woven in a triple story of romance, it became the “Sainted” mountain.

The years that made this story of christening have gone, and too, the rude plate of record was taken from its fastenings and lost to the world forever, save its replica on a film of paper, almost miraculous in its preservation.

Another age has come, the years of the city, the orchard, the vintage; the years of the puffing engine, the harnessed bird of the air, and conquered light of the clouds. It is the day of “Restoration,” and the great mountain feels the footprints and hears the sound of the English-speaking voice.

Sonoma county may well be proud of the little lady who made possible this day of restoration on the old mountain peak.

The notable historical event in all its minute detail and plan, was under the skilled management of Miss Honora R. P. Tuomey, an educator and writer of Sonoma county. She bears a great love for the preservation of these historical landmarks and, too, of telling the story in writing of those days and times, of those men and incidents of early days of this western life.

To Miss Tuomey was given the authority of restoration, and well did she complete the task in every detail. As a princess of the Russians first gave the mountain name, so it was but fitting that a lady of this western land should replace it under the western sun.

It is a long, interesting story, the story of the original plate, of its placement and its final untimely destruction, of which limitations deny in this brief article.

The day of the restoration last Thursday was one of threatening clouds and storm. Invitations had been issued to representatives of the pioneer families of the county and a few guests. Those going to the summit of the mountain from the southern portion of the county chose to go by the Patton toll house trail; those going from this city and section were to climb the mountain from the west, over a trail of steep ascent and heavy with overgrown brush. Those in the party from the Healdsburg section were…

… The copper plates were given by Hood Brothers of Santa Rosa, and the marble tablet by Kinslow Brothers. Harry Parks had charge of the masonry work and bolting to the rock, and was assisted by Mr. Frates…

.. Bolted to the rock on the peak of the great Mt. St. Helena, the story retold, a companion of the mighty storm, the blow of the wind; the drift of the snow and the flash of the clouds of heaven, this tablet bolted to the mountain peak shall stand forever, a leaf from the page of history of the great State of California.

J. M. ALEXANDER.

– Healdsburg Tribune, June 27 1912

RUSSIAN TABLET IS RESTORED ON MT. ST. HELENA

THE 100 TH ANNIVERSARY OF FONT ROSS SEES A NOTABLE CEREMONY IN THE HISTORIC SONOMA PEAK

By Honoria R. P. Tuomey

EARLY in June, 1841, there arrived at Fort Ross an adventurous naturalist attached to the national museum of zoology at St. Petersburg, Dr. P. L. Wosnesenski, commissioned to make collections on the northern Pacific shores of Asia and North America. From the summit of Mount Ross this enterprising man of science saw on the far eastern horizon a quadruple peaked mountain looming conspicuously above the lower summits of the Coast range. Speedily he organized a party, caused a copper plate to be made and inscribed by the artisans at Ross and pioneered a journey to the mountain that until then had been unvisited and unnamed by the Russians who had seen it from afar for a generation.

The little riding party passed across pastoral Sonoma, occupied by Indian tribes not wholly friendly and claimed by Mexico, always hostile to the Muscovite “intruders,” whose stout stronghold she dare not attack.

The complete personnel of this doughty expedition is not revealed in any records of history, but besides Doctor Wosnesenski and his friend, E. I. Tschernech, it included the handsome young Helena, Princess de Gagarine, wife of Alexander Rotcheff, the last governor of Ross settlement, and John Edward Mcintosh, grantee in 1837 by General M. G. Vallejo of the rancho Estero Americano to block Russian encroachments inland; also a small guard of soldiers.

There were some lively thrills on that trip of some forty miles, not the weakest being occasioned by the attempt of old Chief Solano to abduct the princess. Up the rough, almost perpendicular side of the mountain the party mounted to the summit of the north peak, the highest point of elevation. Here upon a flat rock the copper plate was spiked and additional blocks were fitted to form a cairn.

While the others knelt, the princess, raising her right hand, proclaimed the name of the mountain forever “Helena” in honor of her royal mistress and namesake, Helena, empress of Russia. The party returned without mishap to Ross, and the close of 1841 saw the settlements at Ross and Bodega abandoned in obedience to the imperial decree to quit this region, since it had finally been found unsuitable for the purpose for which it was founded in 1812—the victualing of the Russian possessions In the Aleutian islands.

The plate disappeared from the mountain and, while our California historians mention its disappearance, they do not claim to have seen it, and all give its inscription incorrectly in part and misstate the method of its depositing. They give the first word as “Helena,” whereas, that name does not appear, the christening by the princess de Gagarine being entirely verbal. Nor did she call it “Saint Helena.” By two successive coincldences the mountain was named “Saint Helena,” first by a missionary in the early 30’s and in ’42 by Captain Stephen Smith, whose ship, the St. Helena, brought him to Bodega bay. It is stated that a post was erected and the plate nailed thereto, while in fact it was secured to a rock.

The lost Russian plate became one of my quests in my study of local history. For a long while I could find no clew. Finally, while a guest at the Mount St. Helena inn – the tollhouse of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Silverado Squatters” – I was shown by the host Dan Patton, a venerable and widely known Napa pioneer, a copy of an ancient local publication that led me soon to make a pilgrimage to Petaluma. There I called upon a courtly old gentleman for half a century prominent In Petaluma’s business and social life, now, at four score and six, retired within the beauties of his fine old home and big, old fashioned flower garden. After a little teasing of his memory, crowded with the recollections of his long and busy career, Mr. Weston unearthed in his antique secretary a long forgotten scrap of paper, the only copy In existence of the Russian plate. It is of heavy, white linen paper, an octagon 5 1/8 inches in diameter. The face bears this inscription, given here in English:

“Russians, June, 1841, P. L. Wosnesenski III, E. I. Tschernech, Russians.” The latter word, “Russians,” is in Latin. “Jose,” Spanish for Joseph, appears across the upper left corner, and we may but conjecture that this Jose was an Indian or Mexican guide. The remainder of the inscription is in Russian. Upon the reverse side is penned the autographic certification: “Exact copy of the inscription found on a copper plate nailed to a rock on the summit of Mount St Helena by T. A. Hylton in May, 1853.”

“Doctor Hylton gave me this copy, made by himself In 1853,” said Weston. “He was an old friend and fellow townsman. He died on his way east In 1859.”

The seeker after rare historical relics can best appreciate my rapture on that day.

The year 1912 is the centenary of the founding of Ross settlement, and June the anniversary month of the Wosnesenski party’s visit to Mount St Helena. Therefore June, 1912, was fixed as the time to erect a memorial tablet.

The north peak is accessible from more than one point But the only cleared trail leads up the south peak and along the summit, starting at the Mount St. Helena inn, 2,300 feet elevation, on the highway between Calistoga and Middletown. The inn possesses a superabundance of hospitable spirit, but is rather limited as to actual bed and board accommodations. So invitations to the restoration ceremonies were limited to those whose presence was deemed necessary to give dignity and significance to the occasion. The list included Hon. Hiram W. Johnson, governor of California; the consuls at San Francisco of Spain, Great Britain, Russia and Mexico, since each of those countries in succession claimed this territory.

Rev. John R. Cantillon, representing the early mission fathers and particularly Padre Benito Sierra, who as chaplain of the sloop Sonora celebrated at Bodega bay the first religious services ever held on Sonoma soil.

Mrs. L. Vallejo Emparan, daughter of General Mariano G. Vallejo of distinguished memory. Juanita Bailhache Waldrop, Temple Bailhache, Benjamin E. Grant Sr., Benjamin E. Grant Jr., descendants of Captain Henry D. Fitch, accomplished New England shipmaster, Pacific coast merchant and grantee of several large tracts, including the peninsula of Coronado, the Potrero in San Francisco and the Sotoyome rancho near Healdsburg; also relatives of Senora M. I. Lopez de Cabrillo, grantee of the Rancho Cabesa de Santa Rosa and mother of Mrs. Vallejo, Mra Fitch and Mrs. J. B. R. Cooper.

Mrs. Stephen M. Smith and daughter. Mrs. E. Juanita Smith-Rose, of San Francisco, relatives of Captain Stephen Smith, who In ’42 received title to the great Bodega and Blucher ranchos without renouncing his prized American citizenship, but only on condition that he establish certain manufactories. Captain Smith brought round the Horn from Massachusetts a whole shipload of machinery, including the first steam engine ever brought to California, plants for a saw mill, grist mill, tannery, distillery, etc., and four skilled mechanics to erect and manage them. He came the best equipped pioneer that ever settled on this coast. On his way he called at a Peruvian port and married a young Castllian lady, Dona Manuela Torres, to whose brother, Don Manuel, was granted the region about Fort Ross, known as the Muniz rancho.

Miss Elena O’Farrell. daughter of Jasper O’Farrell, who surveyed much of San Francisco, one of whose streets bears his name, and who barely escaped lynching at the hands of irate owners of lots along Market street because he sliced deeply enough into their property to give to the infant city the wide thoroughfare he foresaw it would need. Mr. O’Farrell bought the Ranchos Estero Americano and Canadade Jonive adjoining the Bodego rancho. He made his home at Freestone, renaming his estate the Analy ranch in memory of the principality of Analy in Ireland, ruled for centuries by the O’Farrells, princess of Analy.

Mrs. J. V. A. Frates. daughter of the venerable James McChristian, survivor of the Bear Flag party, and niece of Mrs. Jasper O’Farrell.

George Donner Ungewitter, grandson of George A. Donner of the illfated Donner party.

Mr. Julius M. Alexander, nephew of Cyrus Alexander, a pioneer settler in Alexander valley.

Mr. H. L. Weston, possessor for 59 years of the only existing copy of the Russian plate.

Mr. Donald Mcintosh, grandnephew of John Edward Mcintosh, present at the ceremonies of June, 1841.

Claude O. Howard, district deputy grand president of the Native Sons of the Golden West.

Mr. George Madeira, Mr. Dan Patton and a few other friends, including Mr. and Mrs. Fred. Cummings, Mr. and Mrs. Jirah Luce, Mra A. H. Graeff, Miss Nina Luce, Emile Bachman, T. G. Young, Calvin E. Holmes and Harry Parks, who as a member of the establishment of Kinslow Bros., marble workers of Santa Rosa, who generously donated the marble slab, went along and, assisted by Mr. Frates, made a capital piece of work by securing the tablet In place.

Upon a roughly set tufa platform some 4,500 feet above the level of the Pacific a streak of blue to the west, the party assembled after a reunion and lunch. Three-quarters of California lay smiling below under clear skies. The long serrated wall of the Sierras ran along the eastern horizon, sharply notched where the Truckee flows. Shasta’s white peak to the north, Whitney lording it In the south, Hamilton, Diablo, Tamalpais, Lassen, the northern Buttes lesser features. The bay and city of San Francisco lay near. Sonoma, Napa and Lake counties spread immediately below.

The program opened with the raising of the American flag. Father Cantillon’s invocatlonal utterance followed. Messages were read from Mr. Weston, Governor Johnson and the consuls at San Francisco for Spain, Great Britain, Russia and Mexico, accompanied by the raising In turn of the flag of each of those countries. The bear flag again waved and dipped to Its great successor, the stars and stripes The stories were recited of Cabrillo, Drake, Bodega, the Ross settlement the mission at Sonoma, the raising and lowering of the bear flag and Captain Stephen Smith’s Bodega flagpole. Mr. Patton contributed most of these historical sketches. A poem, ‘The Restoration,” by Julius M. Alexander, was recited by Mrs. Waldrop. Mr. Howard, on behalf of the Native Sons, made a stirring address Benediction and the singing of “America” closed the exercises.

The memorial tablet is of white marble, an octagon 18 inches in diameter and one inch thick. The engraved copper plates are recessed and riveted In place and the slab is fastened with long extension bolts set with solder far into the tufa boulder. Americans are finally commencing to learn that memorial tablets and other monuments are meant to be left intact and not carried away piecemeal as souvenirs. So we feel that this newly erected memorial to the Russians and the Sonoma pioneers will be safe under the sun and the snow on the summit of Mount St. Helena.

There were many intensely funny and a few near tragic incidents on the trip. There was the surreptitious attempt of a well known Healdsburg physician and his son to circumvent the Healdsburg section of the party and scale the mountain by an almost inaccessible ridge to raise a crude Russian flag on the summit and throw bombs at the rest, but the attempt failed ingloriously because those burlesque adherents of the czar got lost and had to return home in chagrin. Then there was the veteran mountain climber, who sat down to rest on the Kellogg trail, was left by his fellows, wandered miles to the inn and finally left on the outbound stage for San Francisco, still laden with 15 pounds of ham, an American flag and a canteen. Again there was the modest Healdsburger upon whom some wag had palmed two left shoes for the climb, and who will, because of an innocent but unlucky observation of Father Cantillon’s, be known for the rest of his life as “the left legged man.” And then the fair daughter of an ancient house, who showed the fearless blood of her ancestors by hastening to view an old, yellow, fierce eyed rattlesnake, declaring it the first of its kind she ever had encountered, and which, through the mercy of providence, was pleased to continue gliding into the brush instead of turning upon its admirer, almost, in her eagerness, treading on its many rattled tail.

– San Francisco Call, July 28 1912

FOURTH OF JULY GREETING FROM CALL

Two Thousand Pounds of Red Fire Will Burn

MESSAGE TO FLASH TO PEOPLE FROM HISTORIC TABLET

In Every Direction Will Be Seen The Call’s Best Wishes and Faith in Great State

When selecting a location to make a red fire display upon the night of July 4, The Call chose a spot full of historical significance, for on the very top of Mount St. Helena, where, on the night of July 4 The Call’s red fire will blaze, stands a bronze tablet defying time and weather and telling of a visit made there in 1841 by the Russians.

The original tablet was long ago removed from its place upon the rocks because of the value attaching to it as an historical relic. This removal took place in May, 1855, in the presence of representatives of the Sonoma pioneer families of General M. G. Vallejo, Captain Henry D. Fitch, Jasper O’Farrell, members of the Donner party and Senora M. Lopez de Carillo, Captain Stephen Smith, C. Alexander of the bear flag party, the Native Sons of the Golden West, the Spanish. British. Russian and Mexican, consuls at San Francisco.

COPY OF TABLET PLACED

Actively in charge of the work was Dr. T. A. Hylton,. who. took a literal copy of the inscription and gave it to H. L. Weston, who a little over a year ago authorized Miss Honora and P. R. Toumey to place upon the rock which bore the original tablet the copy which is now there. The inscription is as follows: “Russians. June, I841. C. L. Vosnisenki III. E. I. Tschernegi. Russians.”

The original tablet was destroyed when the Pioneer building was lost during San Francisco’s great fire, and today all that remains to mark the visit of the Russians to this part of California at that early period of the state’s history is the present tablet, which stands defying the winter’s winds and snows .and the blaze of the summer sun to tell of that visit of the Russians who scarcely realized the splendor of the domain, which they overlooked.

WHERE MESSAGE WILL FLASH

Within 10 feet of the spot where this tablet rests will flare on the night of July 4 a message of good will, from The Call to its California friends…

– San Francisco Call, June 15 1913

Untouched original image of featured graphic. Courtesy Sonoma County Museum

Read More